Jōmon Japan: Prehistoric Culture and Society

Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan’s ancient Jōmon culture is defined as belonging to a period stretching from the emergence of pottery, around 16,500 years ago at the earliest, to the beginning of dry-field rice farming between 3,000 and 2,400 years ago. It is the general name given to the culture of people who began to live settled lives in the Japanese archipelago during this time, engaging in hunting, gathering, fishing, and cultivation, and making use of many different plants and animals, as well as earthenware and stone tools.

A Complex Society

As polished stone tools were in use in the Jōmon period, it can be placed at the Neolithic stage. Unlike the Neolithic societies in Europe and Western Asia at that time, however, there was no organized agriculture or raising of livestock. Nonetheless, the Jōmon people had highly developed ceramic techniques, stayed in the same location throughout the year, and sometimes formed settlements consisting of dozens of residences. They were also able to construct large buildings with lumber as large as 1 meter in diameter, cultivated useful plants like the chestnut tree, urushi (lacquer) tree, soybean, and azuki bean, and mastered such crafts as lacquering and basket weaving.

Re-created buildings at the Sannai Maruyama Archaeological Site in Aomori Prefecture. (Courtesy Sannai Maruyama Jōmon Culture Center)

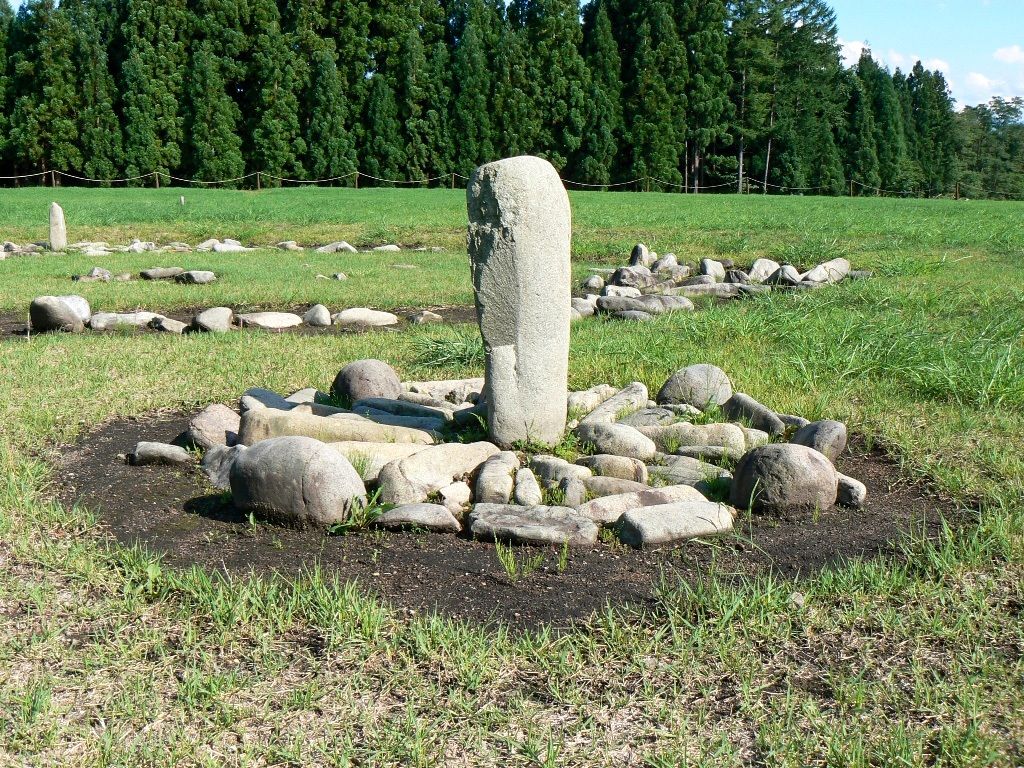

They kept dogs for hunting and even buried them after their death. Their complex spiritual culture is apparent in stone circles and other ritual sites, as well as dogū figurines and stone rods associated with rites. Their graves and grave goods also show that they sometimes formed stratified societies. Accordingly, it is a mistake to see the Jōmon people as simple hunter-gatherers; instead, their livelihood activities, social structure, and spiritual development mean that they should be understood as complex hunter-gatherers. Even at a global level it was rare to find this degree of culture in an economy based on the acquisition of food. Despite its absence of agriculture and livestock, Jōmon culture was comparable in development to its prehistoric counterparts around the world that underwent the Neolithic Revolution from hunting and gathering to agriculture and settlement.

The Ōyu Stone Circles in Kazuno, Akita Prefecture. (Courtesy Kazuno Board of Education)

A stone used as a solar clock at the Ōyu Stone Circles. (Courtesy Kazuno Board of Education)

Death and Rebirth

The Jōmon period is closely associated with pottery. During excavation in the late nineteenth century of the Ōmori Shell Mounds in Tokyo, their American discoverer E. S. Morse found pieces of what he called “cord-marked pottery,” which had been decorated by pushing ropes into the clay. The translation into Japanese of “cord-marked” is jōmon, and the term gave its name to the period in which these kinds of ceramics were produced. Jōmon pottery varies by the time and location in which it was produced. Around 5,000 years ago, in the mid-Jōmon period, elegant, elaborate designs such as kaengata (flame-shaped), ōkangata (crown-shaped), and spiral-patterned vessels were created and used in everyday life in eastern Japan. In the late Jōmon period in Tōhoku 3,000 years ago, a kind of delicate, sophisticated pottery known as the Kamegaoka style was produced, but by this stage there was a distinction between the roughly molded pots for cooking and refined vessels to be used in rituals.

An ōkangata (crown-shaped) pot designated as a natural treasure excavated from the Sasayama Site in Tōkamachi, Niigata Prefecture. (Courtesy Tōkamachi City Museum)

A container with spiral patterns excavated from a site in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture. (Courtesy Morioka Archeological Site Study Museum)

Sometimes pottery was used for burying babies who died shortly after birth. In some cases, the design showed the moment of birth, with the face of the mother at the mouth of the vessel and that of the child midway down. This has led to the theory that Jōmon people thought of the pot as female, and by burying the baby in it, they were expressing a desire for it to be restored to life. Jōmon culture is thought to have had a belief in rebirth and reincarnation.

A pot with a design depicting childbirth excavated from the Tsugane-goshomae Site in Yamanashi Prefecture. (Courtesy Hokuto Board of Education)

Prayers for Fertility

Dogū figurines particularly expressed this Jōmon way of thinking. From their first appearance, they were modeled on women, and increasingly represented mothers in the last stages of pregnancy. It is believed they were used in magic practices that sought to draw on the life-force of women in prayers for healing of injuries and illnesses, as well as for increasing the fertility of the land.

The “Jōmon Venus,” a dogū figurine of a pregnant woman designated as a national treasure, excavated from the Tanabatake Archaeological Site in Nagano Prefecture. (Courtesy Togariishi Jomon Archaeological Museum)

Jōmon people apparently ate all kinds of natural foodstuffs. There is evidence of a particular enjoyment of nuts like chestnuts, walnuts, horse chestnuts, and acorns; game like deer and boar; and fish like sea bream, seabass, and salmon. They processed these and stored them for use throughout the year. Despite their planned consumption, poor weather and other such conditions meant they sometimes went short of food. Alongside their various efforts to get by, they prayed to the dogū to provide food from the land.

A Network Connecting Settlements

Trade between the Jōmon people saw valuable commodities like jade, amber, obsidian, and asphalt transported over long distances from the areas where they were produced. Salt and processed, dried shellfish and fish were carried inland for exchange. Crafted objects like stone arrowheads and axes, shell bracelets, ceramic earrings, and lacquerware were also traded. This suggests there was already an advanced distribution network connecting different settlements.

Jade and other jewels excavated from the Sakai A Archaeological Site in Toyama Prefecture. (Courtesy Toyama Prefectural Center for Archaeological Operations)

Marriages between people from different settlements helped construct and maintain a network for trading commodities and sharing skills. There is also evidence of a stratified society with prestigious goods like jade, amber, and lacquered ornaments concentrated in the possession of certain individuals or families, as in southern Hokkaidō.

Lacquered ornaments excavated from grave 119 at the Karinba Archaeological site in Hokkaidō. (Courtesy Eniwa City Historical Museum)

Linking Past and Present

Contemporary humans (homo sapiens) first came to the Japanese archipelago in the Paleolithic era around 38,000 years ago. They continued to arrive at later dates from the north, via what is now eastern Russia and Sakhalin to Hokkaidō; from China or the Korean peninsula in the west to northern Kyūshū; and from the south through the Nansei Islands. The Jōmon people are essentially the descendants of those who settled in the Paleolithic. Studies have shown that modern ethnically Japanese people get around 12% of their genomes from the people of the Jōmon period, confirmed as being among their direct ancestors by biological anthropology research.

Many of the skills and crafts developed in the Jōmon period continued to be used long after food production was transformed by the introduction of rice farming from the Asian continent around 3,000 years ago, which is seen by some scholars as the start of the Yayoi period. Some even remain as part of traditional Japanese culture today. As such, the Jōmon period has both genetic and cultural links to contemporary Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 28, 2019. Banner photo: A collection of kaengata [flame-shaped] and ōkangata [crown-shaped] pots designated as natural treasures excavated from the Sasayama Site in Tōkamachi, Niigata Prefecture. Courtesy Tōkamachi City Museum.)