Isabella Bird and Her Travels in Nineteenth-Century Japan

Travel Books History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Role of the British Commission

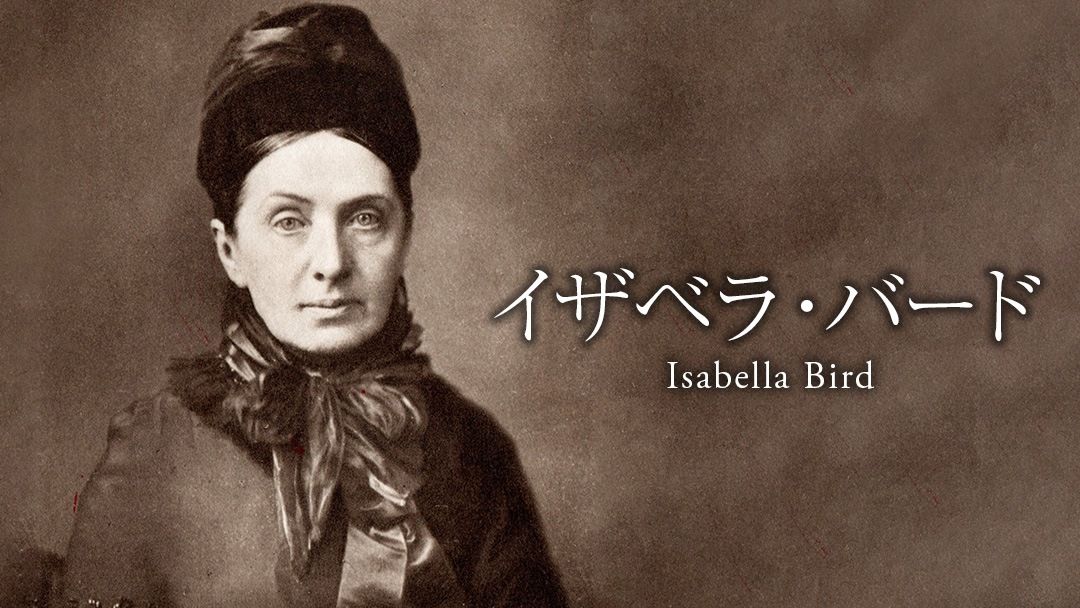

Isabella Bird was born in Boroughbridge, Yorkshire, in 1831, the older of two daughters of a local parson. From 1854 until 1901, three years before her death, she undertook a remarkable series of journeys that took her to every inhabited continent except South America. For the length and geographical breadth of her travels, and the quality of the books and lectures she wrote based on these journeys, which went far beyond simple adventure narratives, she deserves to be regarded as not just one of the top women travelers, but one of the great travelers—period—of all time. In 1891 she was the first woman to be elected fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. One important milestone in her development as a traveler was her journey to Japan, which took place in 1878.

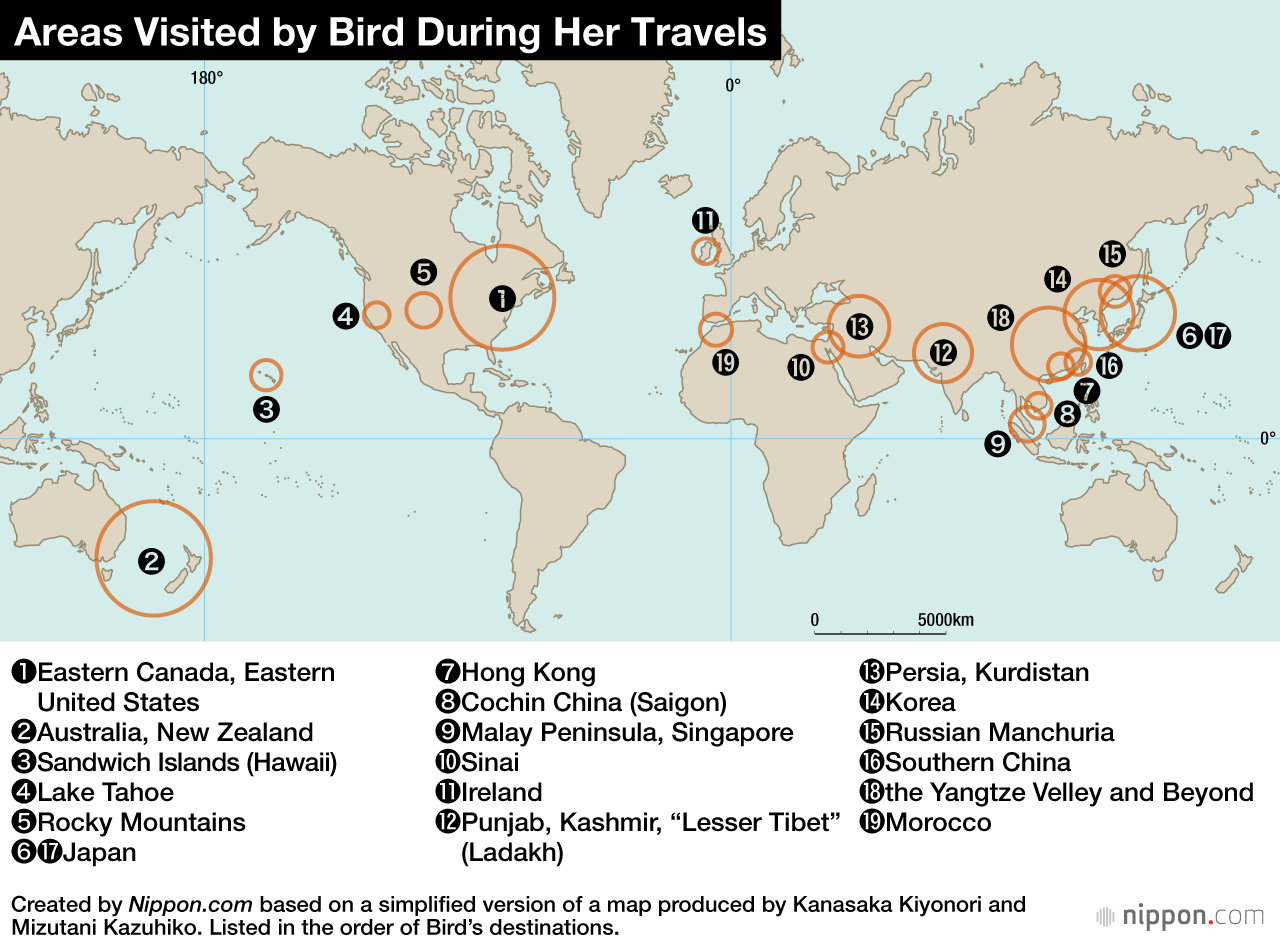

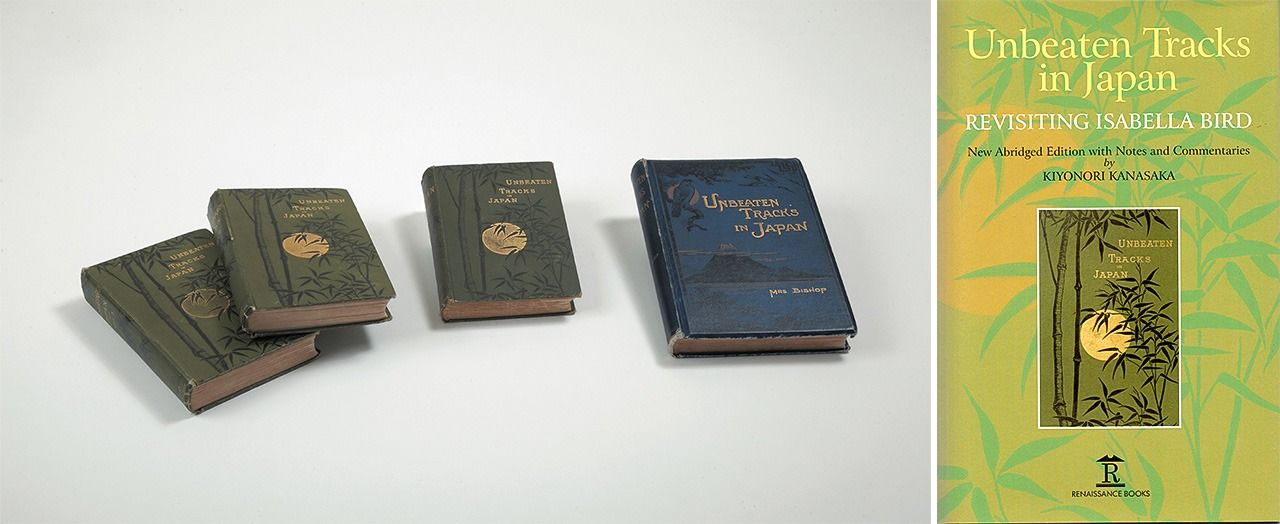

For the third phase of her travels, spanning the locations numbered 6–10 in the map above, Bird left her hometown of Edinburgh on April 1, 1878, sailing across the Atlantic before crossing North America and the Pacific and arriving in Yokohama on May 20. She spent seven months in Japan before leaving from Yokohama for Hong Kong on December 19. Her purpose was to gather facts about Japan, still little known in the West at the time, and write a book introducing the country to audiences back home. This objective was closely linked to her conviction in the value of spreading Christianity; Bird also wanted to investigate the potential for missionary efforts in Japan. The journey was planned by Harry Parkes, a British diplomat who was consul general in Japan at the time. Bird took up his request and worked with a sense of duty and devotion to carry out her mission. The record of her travels in Japan was published in 1880 as Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: An Account of Travels in the Interior Including Visits to the Aborigines of Yezo and the Shrines of Nikkō and Ise, a two-volume work consisting of more than 800 pages. The work was not a compilation of letters written on the road by Isabella to her sister, as has often been claimed, but something closer to a semi-official report.

Three different versions of Bird’s Unbeaten Tracks in Japan. From left: The original two-volume edition published in 1880, the abridged edition of 1885, and the new edition published in 1900 with the addition of 14 photographs. At right, Unbeaten Tracks in Japan; Revisiting Isabella Bird, by Kanasaka Kiyonori. (Photos courtesy of the author)

A Tough Journey

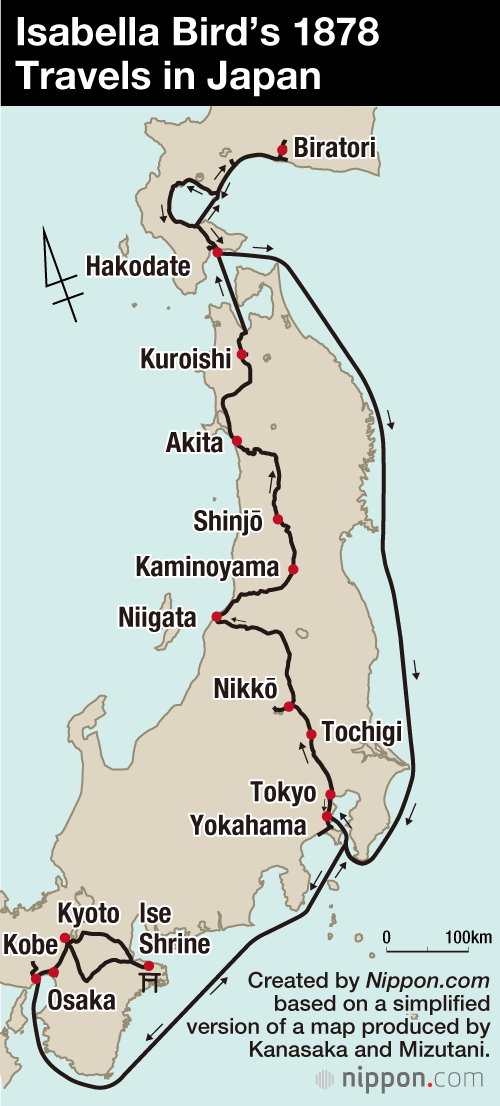

At the time, all foreigner travelers and residents in Japan were subject to restrictions on movement that allowed them to move freely only within ten ri (approximately 40 kilometers) of the five treaty ports, open to foreign arrivals, of Yokohama, Kobe, Nagasaki, Hakodate, and Niigata, and the two cities of Tokyo and Osaka, where foreigners were also permitted. A special permit was required to travel in the “interior” beyond these zones, and even then, there were numerous restrictions on where people could go. Despite these restrictions, Bird decided to travel to Biratori in Hokkaidō, one of the major centers of the Ainu, the indigenous inhabitants of the country’s far north, as well as sites around the nation’s cultural heartland of Kansai and the Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture.

Over the course of her seven months in Japan, she covered some impressive distances. Her travels in Hokkaidō involved a land journey from Tokyo to Biratori of around 1,400 kilometers and a loop of some 2,750 kilometers in total, including the sea voyage back from Hakodate to Yokohama. Her travels in Kansai and Ise involved around 580 kilometers overland plus passage by ship between Yokohama and Kobe, approximately 1,850 kilometers in total. Taken together, these two journeys covered well over 4,500 kilometers. She was only able to undertake a journey on this scale thanks to the hard work of Parkes, who managed to obtain a special permit for travel in the interior with no regional restrictions or time constraints.

Of course, the rigors of travel itself were much harder than they are today. Bird was able to travel by rail only between Yokohama and Shinbashi (in Tokyo) and between Kobe and Kyoto. And travel over long distances by horse was possible only in parts of Hokkaidō. For the rest of the time, she traveled by rickshaw, horse-drawn carriage, on ox-back, or simply by foot along muddy paths. At times, her life was in danger, such as when she had to navigate the swollen waters of the flooded Yoneshiro River in Akita Prefecture. The year’s rainy season was longer and saw heavier rainfall than normal years. For her journey to Hokkaidō, Bird was accompanied by Itō Tsurukichi, her servant and interpreter, and factotum, and it was thanks to his sense of duty that she was able to arrive safely at her destination. In fact, she knew she was going to hire Itō even before she met him for an interview. He not only spoke English well, but had also worked for Charles Maries, the British “plant hunter,” aiding him in his collecting activities during his time in Japan. In applying for Bird’s travel permit, Parkes had included “plant seurvey” among the objectives of her proposed travels.

A Carefully Planned Route

She received important assistance from many other prominent figures, including missionaries and other foreign residents in the treaty ports, among them Heinrich von Siebold, second son of the famous naturalist and physician Philipp Franz von Siebold; Basil Hall Chamberlain, the famous Japanologist; James Curtis Hepburn, inventor of a well-known system for transliterating the Japanese language; Ernest Satow and other Western diplomats; and, on the Japanese side, people from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Interior Ministry, and the Hokkaidō Development Commission in charge of developing the newly incorporated territories in the northern island. All of this came through the good offices of Parkes. Assistance from the Japanese side extended to officials on a more local level, as well as doctors, teachers, innkeepers, and children. Local people put on special performances of winter games and entertainments at the height of summer, and organized things like funerals and wedding ceremonies for the benefit of this exotic visitor.

One of Bird’s major objectives aims in her travels was to gain an understanding of Ainu culture and society and provide a written record of it. In this, also thanks to assistance from Parkes, she received essential help from the Ainu leader Penriuku (“Benri”) and many other Ainu people in Biratori. Wherever she traveled in northern Honshū, local people were fascinated by Bird and strained for a glimpse of her, sometimes poking small holes in paper screens to peek through for a look. As her guide and interpreter, Itō had spread rumors that his employer was a great beauty.

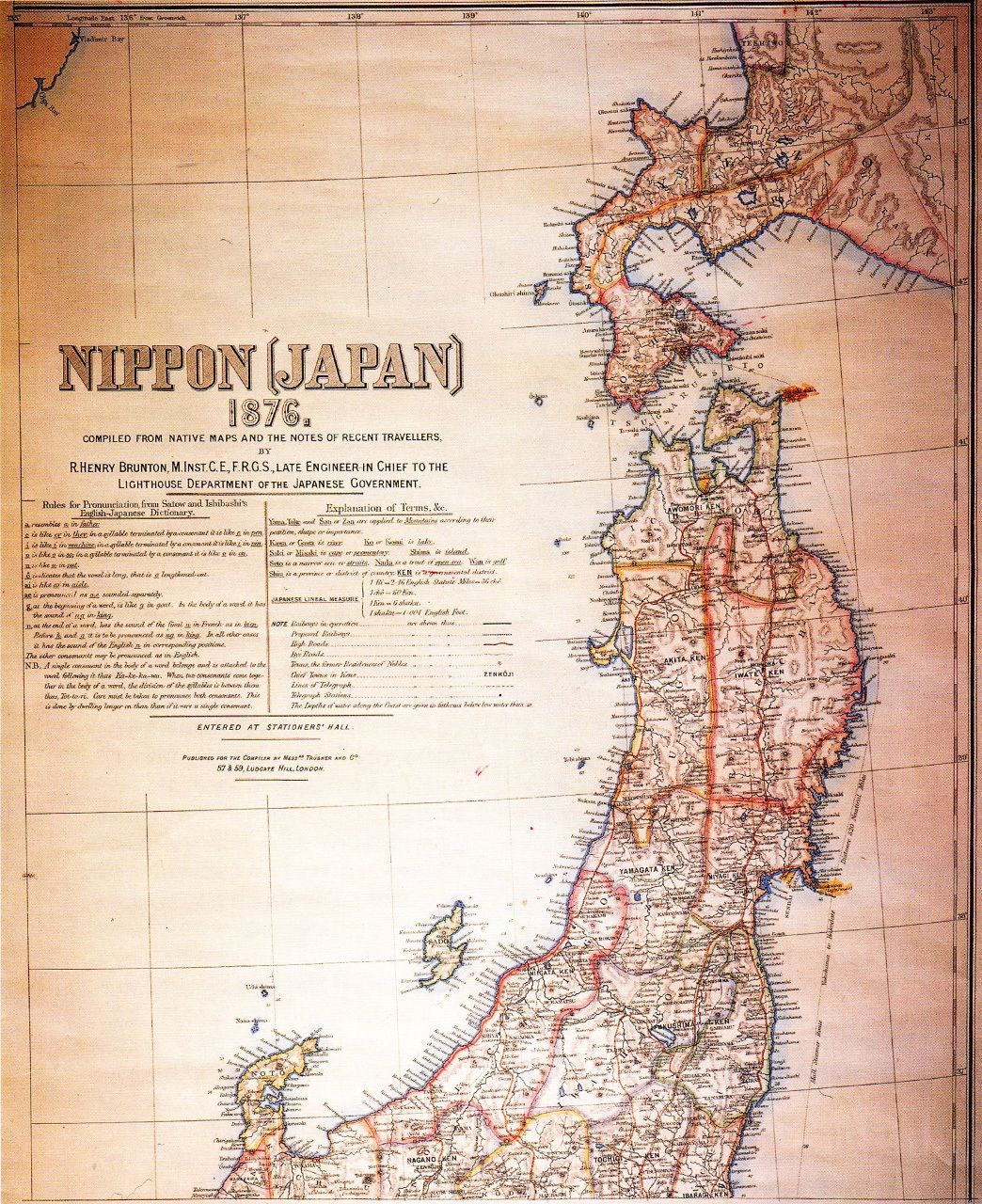

Bird and her travels were often featured in local newspapers, and people were well aware that she was on a journey to observe local customs. Her itinerary was not left to chance but meticulously planned every step of the way in advance in accordance with her aims. For example, at one stage she traveled from Nikkō in Tochigi north to Aizu in Fukushima and then from Tsugawa, Niigata, by boat down the Agano River to emerge at the city of Niigata on the Japan Sea coast. This route was chosen because as a treaty port, Niigata was home to Christian missionaries, and she knew that she would be able to study their activities and learn about local conditions in Niigata. The copy of Brunton’s Map of Japan that she used during her travels was specially prepared for her on Parkes’s instructions.

Brunton’s Map of Japan, carried by Bird on her travels. (Courtesy of author)

Missionary Activities in Northern Japan

Bird’s chief base during her travels was the British legation, where she spent a total of 50 days. Outside Tokyo, five of the eight places where she spent the most time were establishments with connections to Christianity, including missionary houses and the Dōshisha Girl’s School. Nor was her interest restricted to the Church Missionary Society; she also visited outposts of the American Board (the first missionary organization in North America) in Kyoto, Kobe, and Osaka. (She had made an approach to the American Board before visiting Japan.)

The importance that Bird gave to missionary activities is reflected in the fact that she concludes Volume 2 of her book with an argument underlining the significance of seeing the Christian faith more widely accepted in Japan, particularly in Hokkaidō. The Ainu settlement of Biratori was seventh on the list of places she visited by length of stay (the same as Osaka). She stayed for three nights and four days in the home of the local chieftain Benri and worked energetically to learn as much as she could about all aspects of Ainu life and culture. She left a remarkably rich record—and one that was closely linked to missionary efforts to convert the Ainu to Christianity.

Picture of the “Ainu of Yezo” that appeared in Unbeaten Tracks in Japan. (Courtesy of the author)

But even as she dwelled on the importance of missionary activities, she maintained a keen interest in everything she saw and everyone she met on her travels. Her vivid descriptions and clear, honest expressions of her impressions and thoughts are what make her book worth reading today. Her keen powers of observation, honed since childhood, allowed her to record her journey moment by moment. It was this more than anything else that made her such an outstanding travel writer.

An Abridged Edition Leads to a Mistaken View

Bird’s observations were published in a book with the title Unbeaten Tracks in Japan—but that two-volume edition was not the one that most readers around the world know by the title today. The title has become encrusted with misunderstandings, and most people who know anything about the book today think of it as a personal account of an individual journey to Hokkaidō undertaken by an inquisitive, middle-aged British lady. The general view is that the book itself was essentially a compendium of letters written to home during her travels. This has been the mainstream understanding even among scholars who have studied Bird’s work in Britain and the United States. Why?

The main reason is that after the original two-volume edition of Bird’s book was published to great acclaim, the publisher John Murray III, decided to publish an abridged version, reducing the length of the book by half and turning the book into a more typically “feminine” chronicle of travel and adventure. This edition was published five years after the original publication, but with the same cover and binding. This abridged version essentially replaced the two-volume original, and most modern reprints have been based on this abridged version. As a result, many people now assume that this simplified travelogue was the original version.

The same thing happened in Japan. In 1978, a Japanese translation by Takanashi Kenkichi based on the abridged edition appeared. On the back of the popularity for travel writing at the time, the book sold well, and the translation continues to be widely read today, having been reissued in a cheap paperback edition in 2000. A book of commentary by the leading ethnographer Miyamoto Tsuneichi based on this translation has also been published. Although Takahashi knew of the existence of the two-volume original edition, he failed to understand many aspects of Bird’s character and philosophy, the historical background to her travels, and the true nature of the journey she undertook.

This situation has been made worse by subsequent editions that have published piecemeal excerpts in translation on the assumption that the Takanashi translation was 100% reliable. And even editions based on the two-volume original, operating on the assumption that Bird’s journey had been a personal journey and the book based on letters home, chose to render her text in a colloquial style of Japanese (using grammatical forms common in speech and letters, rather than those normally considered appropriate for writing). The market became dominated by translations that were riddled by egregious mistranslations and marred by inappropriate language choices. As a result, although Bird remains better known in Japan today than in her home country of Britain, the problems inherent in reading a text in translation have led to widespread misreadings of Bird’s journey and her book.

To help resolve these misunderstandings, I undertook a new translation of the entire two-volume original edition. The results were published in 2012 and 2013 in four volumes, comprising a complete translation along with copious annotations to help readers understand the true nature of Bird’s journey to Japan.

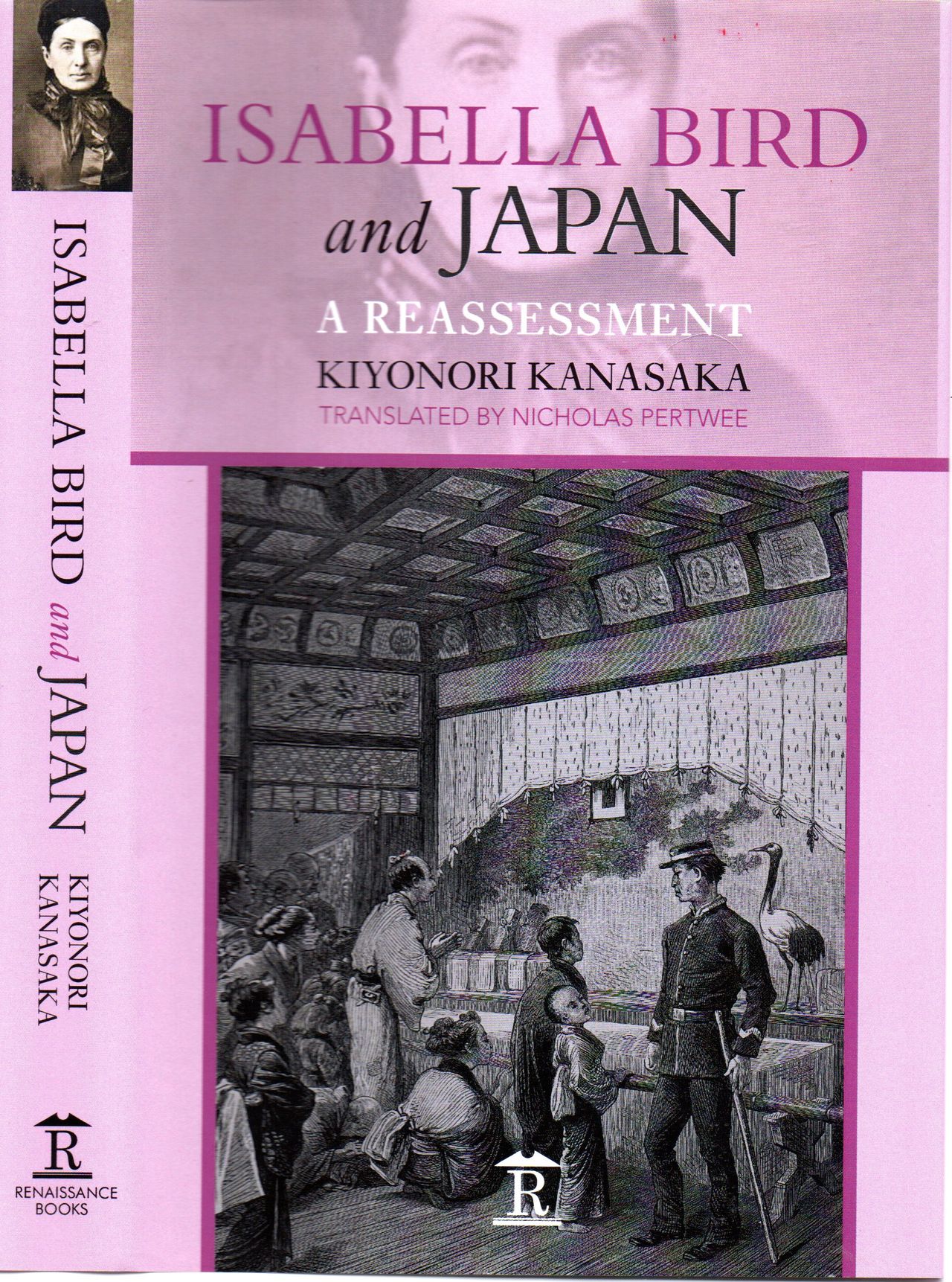

Isabellae Bird and Japan: A Reassessment (trans. Nicholas Pertwee) was published in 2017.

I have also published a translation of the abridged version of Isabella Bird’s travels and a book called Izabera Bādo to Nihon-no-tabi (Isabella Bird and Her Travels in Japan), which provides for the first time a full and accurate account of the events around her famous journey. This was published by Heibonsha in 2014. Moreover, in 2017 I published the English version, titled Isabella Bird and Japan: A Reassessment. I hope that these publications will go some way toward correcting the many misunderstandings about Bird and her travels in Japan and bring the true story of this remarkable woman to a new audience.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Portrait photograph of Isabella Bird, taken in 1881. Photo courtesy of the author.)