Keeping the “Bunshun” Cannons Firing: The Japanese Weekly Outscooping the Traditional Media

People Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Explosive Scoops

Amid a tough climate for the media in Japan, the weekly magazine Shūkan Bunshun has stuck to its guns, uncovering a series of major stories. Its explosive scoops have won it the reputation of having a Bunshun hō, or “Bunshun cannon,” ready to train on straying politicians and celebrities.

In 2020, the magazine has already sold out three issues that in turn published the suicide note by a Finance Ministry official connected to the Moritomo Gakuen scandal, broke the news of an illegal gambling session involving top prosecutor Kurokawa Hiromu, and provided details of comedian Watabe Ken’s adulterous affair.

“Scoops are expensive and also very risky,” says the magazine’s former editor in chief, Shintani Manabu. “Because you’re writing something the subject doesn’t want you to, there are legal risks, and if you’re writing about gangsters, for example, there’s the physical danger of being beaten up.”

When the Nippon Television variety show Sekai no hate made itte Q! invented wacky overseas festivals in 2018, a Bunshun reporter spent three weeks in Laos to expose the deception. The show used the crowd for a festival advertising a well-known brand of local coffee, creating footage for a fabricated celebration in which people purportedly crossed a small wooden bridge on a bicycle. While Bunshun successfully broke the story, it needed time to make its case solid against a major force in the TV industry.

Strength in Numbers

In July 2019, Kawai Anri, the wife of former Justice Minister Kawai Katsuyuki, was elected to the House of Councillors. Bunshun sent 12 reporters to Hiroshima to follow up on suspicions that she had exceeded legal daily pay allowances for her staff. This made it possible to talk to almost all of the 13 campaign staffers simultaneously.

“Visiting at different times would give them the chance to get their stories straight. You can learn a lot from people’s behavior when they’re unprepared and under pressure. Sending twelve people and coming up with nothing means risking having nothing to fill pages with. But the biggest risk comes from printing a half-baked story.”

Printing a story without sufficient evidence to back it up can lead to an expensive day in court. “I’ve taken the witness stand any number of times in libel cases,” Shintani says. In the Kawai case, the Bunshun story stood up, and the couple was arrested in June 2020 after more serious allegations of vote buying.

Embezzlement at NHK

Shintani recalls that when he was starting out, weekly magazines were seen as occupying the bottom rung of Japan’s media hierarchy. He joined Bunshun in 1989 at the age of 30. With no other means of acquiring information, he often went to the headquarters of Aum Shinrikyō in Minami-Aoyama, Tokyo. Six years before it launched deadly sarin attacks on the capital’s subway system, the cult was drawing media interest, and Shintani would talk to other reporters who gathered there.

“NHK was at the top of the hierarchy, followed by the major newspapers, and then other television stations. My job then was to be liked by the ace journalists covering politics, social issues, and economics. Insisting I knew nothing, I shamelessly got them to teach me the trade. I also got a lot of ‘leftover’ stories that they weren’t able to write for their own outlets.”

Shintani felt the tide turning when breaking a story about embezzlement by Isono Katsumi, a producer of NHK’s New Year show Kōhaku uta gassen in 2004. “The producer made payments to a writer who didn’t actually do any work, and received kickbacks in turn. We were up against the power of NHK, so we wanted decisive evidence. I had our then reporter Nakamura Ryūtarō go undercover for almost a month and he got his hands on payment statements.

“Ultimately, Isono was arrested, and newspapers and other TV stations followed up on it. Nakamura and I were like, ‘Yes, Yomiuri Shimbun. Next, Mainichi Shimbun,’ as reporters came to make contact every day and hear what we had to say. ‘This is the complete opposite of how it used to be!’ I thought. It was an amazing feeling.”

The people with the information are in charge and can control the situation. Shintani was convinced that this was the way forward for Bunshun. “The Kōhaku producer scandal led to a movement not to pay license fees, which forced reform at NHK. I think it had some positive effects.”

Keeping the Cannon Firing

As Shintani has risen through the organization, he has become more focused on the value of scoops. “We printed and sold more than 500,000 copies of the Watabe Ken issue. Taking a broader perspective, however, there’s no denying the declining returns from print magazines. It’s impossible to secure ample budgets, and if cost cuts are forced on you, you can’t assemble quality personnel, meaning less interesting content, and greater vulnerability to risks. Making the shift to digital was an urgent issue.”

As scoops take time, and are expensive and risky, there needs to be a constant cycle of stories coming in and earning money. In other words, the Bunshun cannon needs to keep firing. The weekly goes on sale in Tokyo and other areas on Thursdays, but articles are sold separately online the previous day.

“With the Watabe story, we earned 12 million yen, selling more than 40,000 copies online at 300 yen each,” Shintani says. “We also published two digest articles, which got a total of around 80 million page views. As a rule of thumb we can expect about 30 percent of this figure to come in as advertising income, that’s another 24 million yen.”

There are also fees for television stations of ¥50,000 for using an article once in a show and ¥100,000 for videos. “When TV stations asked to use our stories, we used to happily tell them, ‘Go ahead, it’s good PR for us.’ But they might spend a whole hour on just one, like the Becky adultery case. The viewers would feel like they’d had enough and not buy our magazine.

“For a content-based business like ours, we needed to start charging. This allowed us to develop a major source of income in addition to the sales of the print magazine. This is also a resource to fund work on new stories.”

Shintani Manabu of Shūkan Bunshun. (© Takayama Hirokazu)

A New Source for Tips

As the magazine published a series of exclusive stories, the quality of information that came to its Bunshun Leaks service rapidly increased. Shintani say that the idea faced opposition when he proposed it at a board meeting, but the service now fields over a hundred tips a day.

“You won’t believe this, but the first thing we tell people is that ‘we don’t buy information.’ If it ends up becoming an article, there’s a payment, but only around the same common-sense amount as for a manuscript.”

Although Bunshun does not offer large payouts, it continues to receive reliable tips with the potential to become stories. The magazine got started on the Kawai story through information received via Bunshun Leaks. “The first line of the message said, ‘At first I thought about taking this to the police, but they’d probably suppress it, so I’m sending it to you at Bunshun.’ Another part said, “However powerful the opponent, you’ll fight without showing any deference. Or you’ll take the risk, spend money, and bring the scandal to light.’” Shintani shows his pride: “That’s our branding.”

The magazine’s investigative stories bring in income and boost its reputation, so it can receive more information. This virtuous cycle means Bunshun now has a near monopoly on such exclusives.

“When Bunshun used to publish its scoops, some media outlets used to credit them to ‘a weekly magazine’ or not at all, simply saying, ‘it was learned that. . .’” Shintani says. He began calling them up to insist they include the magazine’s name. “We live or die through our scoops, and I wanted them to win more respect. Finally NHK and the Yomiuri Shimbun started saying, ‘According to Bunshun. . .’”

Fighting It Out

Its success has led to reporters from other magazines and even major newspapers seeking work at Bunshun. Shintani says that it is good to see their passion. “When I meet them, I know the kind of person who can get a scoop. Basically, they need three qualities: personability, audacity, and sincerity.”

Shintani sees media rivals as too cautious to offer serious competition, as they fear getting sued, and are out of practice. “When you lose your muscles, you can’t run when you need to, and your punch is weak. Meanwhile, we’ve focused solely on winning those kinds of battles.

“I sense that across society, people are losing their defiance when faced with powerful adversaries. Even if it’s Don Quixote, there should be one media outlet ready to stand and fight it out, armed with facts as weapons.”

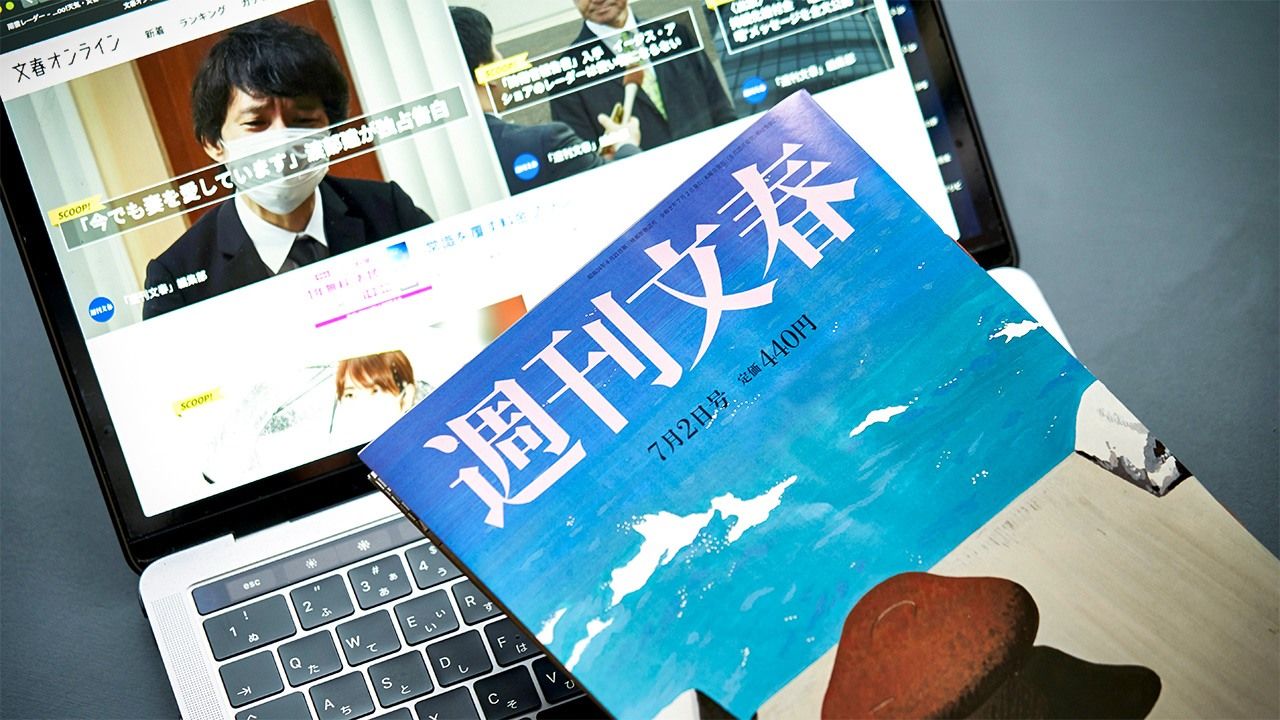

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The July 2 issue of Shūkan Bunshun. © Takayama Hirokazu.)