São Paulo’s Asiatown: A Little Piece of Japan Halfway Around the Globe

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

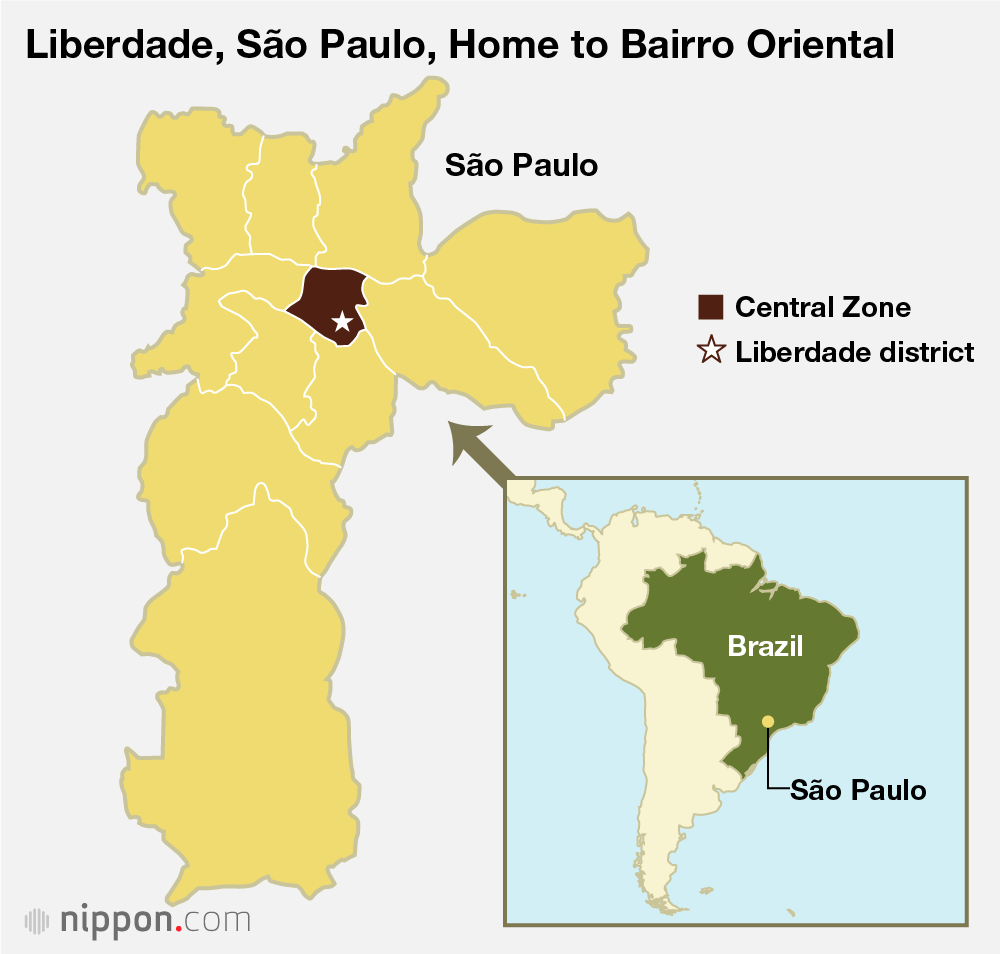

Japanese neighborhoods, such as Little Tokyo in Los Angeles and Vancouver’s Powell Street Area, can be found around the world, but Bairro Oriental, in São Paulo, is perhaps the biggest.

Imin ga tsukutta machi San Pauro Tōyōgai: Chikyū no hantaigawa no Nihon kindai (The Town Japanese Immigrants Built on the Other Side of the World: Bairro Oriental in São Paulo).

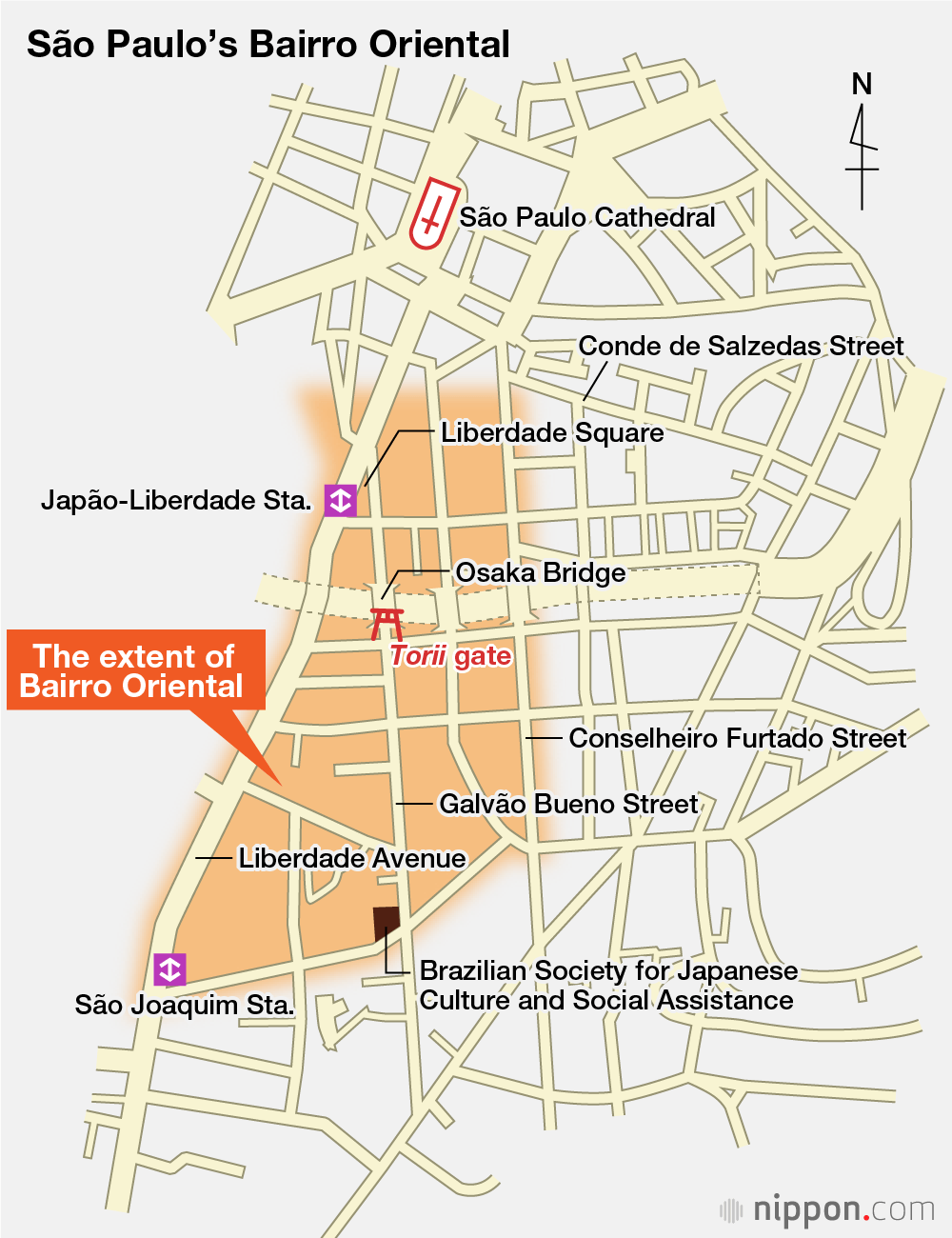

This Asiatown, in the center of São Paulo, South America’s largest city, measures roughly 500 meters east-west and 1,500 meters north-south. It is one of the city’s key tourist attractions, known in Portuguese as Bairro Oriental, or by the name of the local subway station, Liberdade. Migration from Japan to Brazil started early in the twentieth century, and steadily grew. Through many ups and downs, the Japanese-Brazilian population has reached around 1.9 million, the largest worldwide, making Liberdade the largest ethnically Japanese settlement outside of Japan.

When I first visited Brazil in 1992, I was taken straight from the airport to Bairro Oriental. After spending 17 years in Brazil, I published a book about the history of the neighborhood in July 2020. It recounts stories of Japanese people who traveled halfway around the world, and the community they created over the span of a century.

Japanese Cinemas Spark the Rise of Japantown

Mass immigration from Japan to Brazil began with the Kasato Maru, which sailed from Kobe to Brazil in 1908. The ship carried nearly 800 migrants, most of whom were contracted to work on coffee plantations inland of São Paulo. Around 10 were free migrants, who settled in the city.

In the 1910s, scores of laborers in São Paulo state deserted farm work and moved to the city. Many settled near the long, sloping Conde de Salzedas Street, forming the first Japanese community. Later, as their economic standing improved, they shifted uphill, and “Japantown” expanded. The neighborhood saw increased Japanese migration and greater prosperity in the 1930s, but with the outbreak of the Pacific War, people of Japanese ethnicity were denounced as foreign enemies.

Following the war, Japantown grew around Galvão Bueno Street. Surprisingly, the change was mostly triggered by the opening of Brazil’s first Japanese movie theater, Cine Niterói, in July 1953. Cine Niterói was founded by Tanaka Yoshikazu, a first-generation Japanese grain broker.

The five-story complex was located along Galvão Bueno Street, just below Liberdade Plaza, where Osaka Bridge is today. It was a cultural and entertainment center for the Nikkei community. The first-floor cinema had capacity for an audience of 1,500, while the upper floors housed a restaurant, hall, and hotel. On weekends, the area around the cinema thronged with crowds in search of entertainment. Later, three rival cinemas launched nearby: the Nanbei Gekijō, Cine Tokyo, and Cine Nippon. Restaurants and other shops also opened to cater to the crowds, creating a shopping district somewhat reminiscent of Japan.

![Facade of the Cine Niterói (from Colonia Geinoshi [History of Art and Entertainment in the Japanese Brazilian Colony])](/en/ncommon/contents/japan-topics/480990/480990.jpg)

Facade of the Cine Niterói (from Colonia Geinoshi [History of Art and Entertainment in the Japanese Brazilian Colony])

In April 1964, the São Paulo Nihon Bunka Kyōkai (São Paulo Japan Culture Association) Center Building, later the Brazil Nihon Bunka Fukushi Kyōkai (Brazilian Society for Japanese Culture and Social Assistance), was constructed south of Galvão Bueno Street, at the intersection with São Joaquim Street. Initially, the building had four floors and an area of 3,734 square meters, but it was subsequently enlarged. It was quite striking because, although Liberdade is a high-rise district today, in those days, it was mostly aging two-story structures. The Japanese cinemas and shopping area, combined with the cultural center, formed the core of what later evolved into Bairro Oriental.

The present-day Brazil Nihon Bunka Fukushi Kyōkai (Brazilian Society for Japanese Culture and Social Assistance).

Chinese and Korean Immigration Transforms the Area

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Japanese street of Galvão Bueno came under threat from a revamp of the inner city, and subway construction. Cine Niterói was forced to relocate to the main street of Liberdade to make way for an expressway. Many other businesses left due to the ongoing construction. But community leaders including Tanaka Yoshikazu and the entrepreneur Mizumoto Tsuyoshi turned this into an opportunity to develop the neighborhood.

In November 1974, the area was reborn with the addition of a torii (shrine gate), hanging lanterns, and a Japanese garden, and it was rechristened Bairro Oriental. New events were introduced, including a Tōyōichi (Asia market), hana-matsuri (floral festival celebrating the Buddha’s Birthday), Tanabata festival, and mochitsuki (rice-cake pounding) festival. These celebrations were based on Japanese traditions, tailored to the local culture.

The Japanese garden on Galvão Bueno Street in São Paulo’s Bairro Oriental.

Tanzaku upon which people write wishes during the Tanabata star festival.

Liberdade Square comes alive during the weekend Tōyōichi market days.

The 1960s saw an influx of immigrants from Taiwan and South Korea. Many spoke Japanese, due to their history as former Japanese colonies, and so they came to Bairro Oriental seeking information in a language they knew. As time passed, they became key members in the community, and were joined by immigrants from mainland China in the 1990s.

Now, Conselheiro Furtado Street, at the eastern edge of Bairro Oriental, is home to the São Paulo Chinese cultural center, the Cantonese Association of Brazil, the Kodoin Kwan Yin Temple of Brazil, and other facilities of the Chinese community, along with Taiwanese and Chinese shops and restaurants. Japanese businesses now sit among Chinese supermarkets, hotels, bars and eateries, karaoke joints, hair and beauty salons, doctors, travel companies, schools, and so on. It has started to feel like a mini-Chinatown.

The São Paulo Chinese cultural center on Conselheiro Furtado Street.

A Base for Nikkei Popular Culture

In the 1990s, as the Chinese population grew, there was also an increase in the number of Japanese-Brazilians going to Japan for work. The population was aging and hollowing out, and the Nikkei community seemed on the verge of disintegration. But there was growing interest in Japanese popular culture among youth, independent of the Nikkei community or even the Japanese language. Bairro Oriental was seen as the embodiment of Japanese culture, reinterpreted and reinvented through Brazilian eyes.

Billboard for a ramen restaurant in Bairro Oriental.

Sushi, for example, is popular in Brazil, and while some Nikkei chefs prepare it in the traditional style, modern sushi bars incorporate local ingredients, such as avocado and guava. There is a flourishing Nikkei cuisine with Japanese roots, but catering to Brazilian tastes.

In the early 2000s, young cosplayers and pop idol fans began congregating in Bairro Oriental on weekends, and the area became a beacon for Japanese popular culture. Brazil’s street-art, unlike typical graffiti, includes works that reflect the influence of Japanese anime. The fashion and art are not simply copies of Japanese styles, but include Brazilian content, localizing Japanese fads to create a unique Nikkei culture.

Anime-influenced street art along Galvão Bueno Street.

Now, Bairro Oriental attracts young Japanese-Brazilians who have worked and lived in Japan and Brazilian Japanophiles. It provides a focus both for nostalgia and adoration of Japan.

On weekends, Liberdade Square attracts throngs of Japanese anime fans.

The facade of Liberdade’s Bradesco Bank resembles a Japanese castle.

COVID-19 Hits the Community

With the spread of COVID-19 in 2020, the city of São Paulo issued a lockdown order. Bairro Oriental, previously so crowded on weekends that you could hardly walk, became a ghost town. Restaurants in the area turned to takeaway and pre-packaged bentō meals, but the impact on other businesses has been immeasurable. In April, the owner of a Taiwanese supermarket on Liberdade Square, died from the disease.

According to the Nikkei Shimbun, a newspaper for Japanese-Brazilians produced in the community, and my friends in São Paulo, shops started to reopen from July, after the lockdown was lifted. In accordance with the city’s health department guidelines, store customers have a temperature check and disinfect their shoes and hands before entering. Chopsticks and hand towels are sealed, and customer numbers limited to one-third of capacity.

The Brazil Nihon Bunka Fukushi Kyōkai (Brazilian Society for Japanese Culture and Social Assistance), which closed temporarily, reopened on July 15 last year. The association held cultural events online, via YouTube and Facebook. Shifting such work and events onto the web is expected to accelerate the transfer of the mantle of the Nikkei community to the next generation. But given the older generation’s preference for analog interaction, and the lack of regional communications infrastructure, activities will continue both on- and offline for now.

I spoke with Toshio Ichikawa, chairman of the Federação das Associações de Províncias do Japão no Brasil, or Kenren. A second-generation Japanese-Brazilian, born in Aliança, in inland São Paulo, he graduated from the Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica. He said that Kenren had shifted most of its operations online, and his weekend family gatherings were on hold, but he was pleased to report the birth of his third grandchild. The organization hosts the Festival do Japão, the largest annual event in the Nikkei community, but it had to be postponed. Meanwhile, on November 17, Nikkei youth ran an online festival that reached a global audience via YouTube.

COVID-19 has hit Brazil hard, infecting over 5 million people by October 2020, the third-highest number worldwide. Over 150,000 people have died from the virus, the second highest toll after that in the United States. Despite the heavy toll from the pandemic, the Nikkei community, which has overcome many difficulties in the past, is finding new avenues for interactaction. Although there is still no clear end in sight, they hope for a revival in Bairro Oriental, including virtual platforms.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The vermilion torii and suzuran lanterns that symbolize São Paulo’s Bairro Oriental. All photos courtesy of the author.)