João Gilberto: How the Bossa Nova King Took Japan to His Heart

Music Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Unique Style of the Father of Bossa Nova

INTERVIEWER Mr. Miyata, you once said that João Gilberto’s redefinition of samba was shaped by his unique style and approach to life: that it was essentially João and his personality that created bossa nova as we know it.

MIYATA SHIGEKI If you think about what makes his music special, I suppose the first thing that comes to mind would be his sense of harmony. The harmonies he came up with were extremely innovative. And then his fresh approach to the guitar and singing. He took the samba form he loved and performed the music in his own style: and what emerged was bossa nova.

INTERVIEWER Mr. Itō, you once wrote that bossa nova was born out of the encounter between João Gilberto and Antônio Carlos Jobim.

ITŌ GORŌ As a composer, Jobim was already writing before he met Gilberto. But the songs that became bossa nova standards might never been written if they hadn’t come together. We’d have been living in a world without “Girl from Ipanema” and “Samba de Uma Nota Só,” the “One Note Samba.”

Gilberto’s approach to playing basically encapsulated the traditions of Brazilian guitar music. Brazil seems to produce at least one great guitar colossus in every generation, just as each generation has its superstar soccer players. In soccer, you have Pelé, Zico, Ronaldo . . . It’s the same with the guitar: there’s this rich genealogy that goes down through the generations: Garoto, Luiz Bonfá, Gilberto . . .

Nor can we forget his unique sense of rhythm when talking about what made him special. Some people say that he managed to incorporate elements of all kinds of different instruments and play them on a single guitar. My feeling is that he basically perfected the kind of minimalist expression that you can achieve with just his one instrument.

MIYATA I think one thing to notice with Gilberto is that his guitar and voice are not always exactly in synch. They each have their own groove, and the two exist in separate dimensions slightly apart from each other. I always get the feeling that the reaction between these two elements produces causes a third strand of time to appear. No one else can sing the way João Gilberto sings.

ITŌ It’s a polyrhythmic sense of time. And you can tell that he’s enjoying playing the role of both singer and instrumentalist within the same performance.

Always Singing and Playing

MIYATA Gilberto loved a live setting where he was free to play with the groove and enjoy himself in the moment. The repertoire he could play on the guitar ran to 500 or 600 songs. He just really loved to play. I remember in Japan, after the show was over, he’d still be sitting in his hotel room with a guitar in his hands, trying new things: “Maybe these chords would have worked better for this song . . .”

ITŌ It’s basically impossible to imitate João’s style of singing. It’s not just his enunciation and his perfect sense of pitch—it’s that remarkable sense of rhythm. And his breath control: He always knows exactly where to take a breath between the words. It’s perfectly calculated. And each breath lasts so long, letting him sing those long lines in a single breath. To be able to do that without any kind of audible straining in the voice requires superb technique. He must have worked extremely hard to be able to do that.

MIYATA I think he loved playing and singing so much that doing it for eight hours a day wouldn’t even have felt like practicing: he was just doing what he loved.

The Room Service Hamburger that Meant “Yes”

INTERVIEWER Let’s talk about the concerts he gave in Japan later in his life. Was Gilberto open to the idea of performing here right away?

MIYATA When I went to Brazil in 1989, I became friends with his wife, Miúcha. She used to have me over to the house and things. So when I started to think about inviting him to Japan in 2000, the first thing I did was phone Miúcha, and she put me in touch with his agent in Brazil.

I went to Rio, but Gilberto was away on tour. He phoned me at my hotel. We chatted about things, and he even played and sang for me, over the phone. And then this hamburger was delivered to my room. Apparently, that was something he often liked to do if he felt he’d clicked with someone. Miúcha told me: There’s your answer. That means he’ll go to Japan. I guess you could say he was slightly eccentric!

The crew working on the tour in Japan had all been told to be on their guard and basically be prepared for whatever might happen. The arrangement was that he’d arrive in Japan ten days before the first concert. In fact, he didn’t turn up till the day before. And then for the rehearsal before the opening performance, he showed up at the venue an hour after the show was supposed to start. We had to keep the audience waiting outside while he ran through a quick one-song sound check. He wasn’t picky about the sound. He was quite laid back about it all: “Oh yeah, sure, it’ll be fine.”

ITŌ I heard that he made a request to turn off the air-conditioning.

MIYATA That’s right. He said it was bad for his throat. And no cold drinks, either. He drank everything at room temperature.

INTERVIEWER What kind of image do you think he had of Japan as a country?

MIYATA The first time we spoke, I remember him talking about haiku and Zen, but how much he really knew about those subjects I’m not sure. His first visit in 2003 happened to coincide with the September sumō tournament. I’d visit him in his hotel room and find him still in his pajamas, watching the sumō on the TV. As you know, the live broadcasts end at six o’clock every day, and then it would take him at least an hour to get ready. But the concert’s supposed to start at seven . . . Gilberto had this reputation for always being late, so we printed a warning on the tickets for the concert: “Starting time may be delayed without notice at the artist’s discretion.” I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like that on tickets for a concert by any other performer. “Better late than never” was something he used to say all the time.

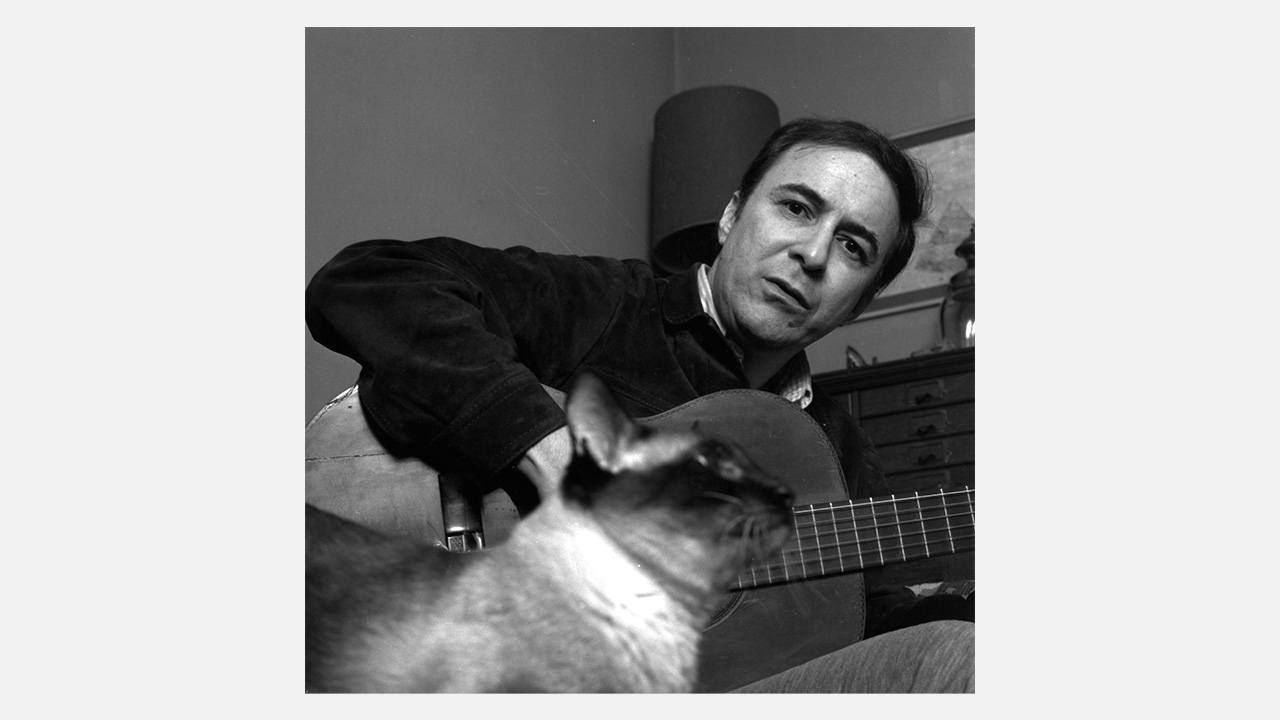

João Gilberto performs on his first visit to Japan in 2006. (© Nirei Hiroshi and Yokoyama Shin’ichi)

The Quietest Audiences in the World

INTERVIEWER He used to change the running order from day to day, I understand.

MIYATA Right. He had these big sheets of paper with the titles of about twenty songs written on them. There were three sheets of paper like that, on the stage floor. And after he finished each song, he’d sort of look down at these sheets of paper and choose what to play next. That was his approach to setlist planning.

ITŌ And you couldn’t say anything between the songs. Sometimes it would go on for 20 minutes. But even so, he still held the audience’s attention. There was something mesmerizing about him.

MIYATA Although in Osaka there was one heckler who shouted out: “Come on, get on with it! We haven’t got all day!”

ITŌ His show at the Tokyo International Forum was an amazing experience. Despite the size of the venue, around 5,000 seats, the atmosphere was very intimate. Of course, musically, he was doing these amazing things right there in front of your eyes. But even before that, there was this strong emotional connection. I’ve never experienced anything like it at any other live performance. I think Gilberto picked up on that special atmosphere too, and I’m sure everyone in the audience felt it. And the applause, when it came, was rapturous and heartfelt. It was a unique experience.

INTERVIEWER People often say that Japanese audiences are the quietest in the world—that there’s nowhere else where large audiences will concentrate so intently on the music as they do here.

MIYATA Even in Japan, I don’t think many audiences have ever been as quiet at that!

ITŌ I remember, you almost felt you should hold your breath.

MIYATA In the second half of the performance, there was a place where he sang the same words about five or six times, until it started to sound like an incantation. It didn’t feel like one guy on stage singing to 5,000 people in the audience. It was as though he was singing personally to every single one of the people in the audience. And I think that brought him great pleasure and happiness too.

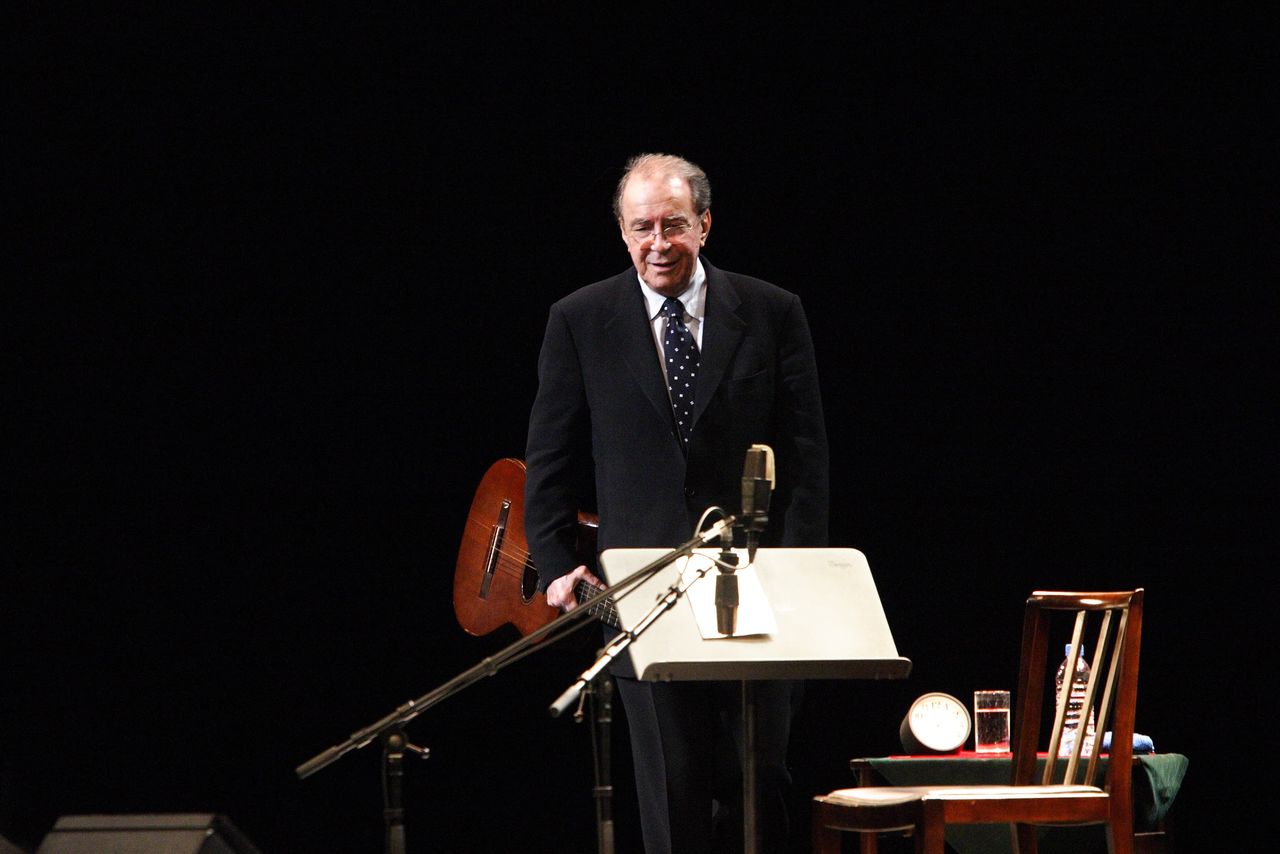

João Gilberto on stage in Japan, 2006. (© Nirei Hiroshi, Yokoyama Shin’ichi)

INTERVIEWER Presumably that was behind the idea—put forward by the musician himself—to release a CD of his performances in Japan.

MIYATA Right. In fact, we hadn’t even considered the possibility of a CD until Gilberto suggested it, so at first the idea came as a complete surprise. We handed him the recordings we had made of the performances each day. Then one day, he said, “Come over and listen to this with me.” And the recording he brought out was the one from September 12. He asked me what I thought, and I said I thought it sounded great. He said, “OK, let’s put this one out on CD,” and that was pretty much it. There was nothing in the contract about a CD. In fact, there was a clause that said: “CD recordings of the performances will not be made.” So that’s why the recording is in mono.

INTERVIEWER It sounds as though there was something in those performances that struck the performer himself as something special.

MIYATA I think so. And when I suggested the idea of coming back again the following year, he agreed right away. Eventually, we ended up arranging performances in Japan in 2004 and 2006 as well.

A Celebration of 90 Years

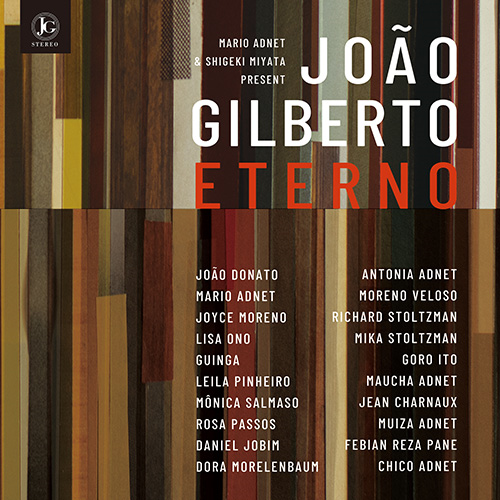

INTERVIEWER Finally, we have João Gilberto Eterno, the tribute album to celebrate what would have been his ninetieth birthday this year. Mr. Miyata, you helped bring together a group of artists who loved and respected Gilberto to record new performances of music associated with him. The album features some of the superstars of Brazilian music, as well as you, Mr. Itō, and Lisa Ono representing Japan. What was the process behind assembling those artists and deciding who would perform which songs?

MIYATA Well, in addition to pieces essential to any conversation about João’s music, we also included several tracks that he wrote himself. His work as a composer is surprisingly unknown, so we deliberately wanted to include as many of those songs as we could to bring some of that work into the spotlight.

ITŌ How did the recording process work out, given the pandemic situation in Brazil and other countries?

MIYATA Unfortunately, we were forced to do quite a lot of it remotely. Some of the musicians on the record live in São Paulo, others in Brasilia.

INTERVIEWER Another new release is Amorozsofia: Abstract João by the Itō Gorō Ensemble. There was also a series of radio specials in Tokyo to celebrate his birthday in June. What makes João’s music so popular with Japanese audiences?

ITŌ There’s definitely something—an aspect of his music that isn’t immediately accessible. It can be difficult to appreciate at first. And a lot of Japanese music fans can be quite passionate, almost obsessive about things. I think maybe that ability to produce this unique, slightly offbeat music—something that not just anyone can copy—is part of what appeals to the tastes of some of the hardcore aficionados in Japan. Plus, the man was a legend. Japanese audiences have a special respect for people like that, who occupy an unshakeable position in the history of their field.

Tribute Album Information

Various Artists: João Gilberto Eterno

CD「JOAO GILBERTO ETERNO」© Universal Music

Itō Gorō Ensemble: Amorozsofia: Abstract João

CD「AMOROZOFIA ABSTRACT JOAO GORO ITO ENSEMBLE」@ Universal Music

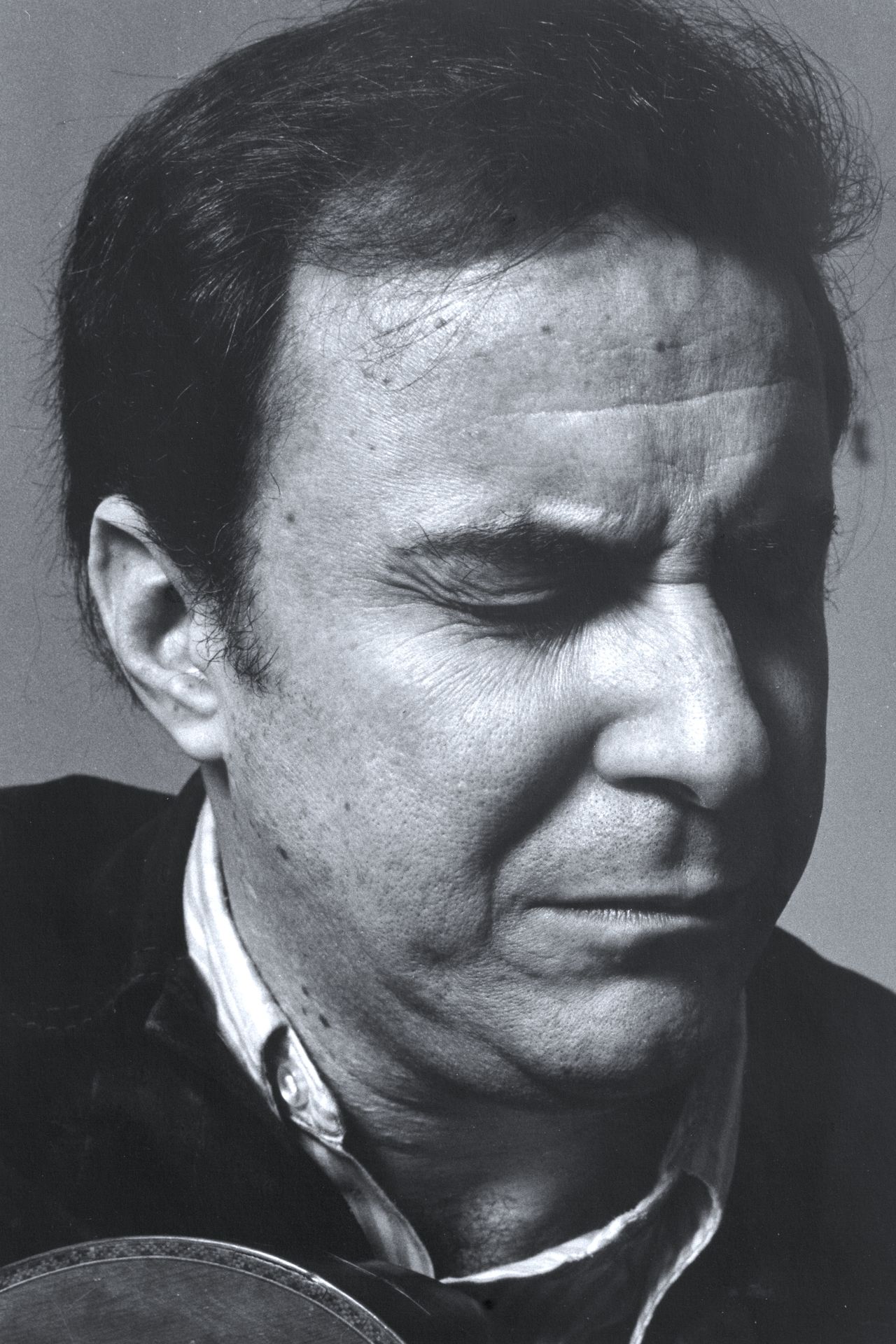

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Doi Hirosuke.)