Prefectures, Power, and Centralization: Japan’s Abolition of the Feudal Domains

History Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Independent Military Reforms

In June 1869, the Boshin Civil War came to an end with the final overthrow of the shogunate. The victors, the new Meiji government, moved quickly to take a first symbolic step to abolition of the domains, ordering them to give up their registers to return territory and citizens to the state. Nonetheless, the domain leaders remained in control under the new titles of governors. The national government had no real power at the time, and could not eliminate the domains by force. The soldiers that had fought in its army to overcome the shogunate returned home to their domains once the civil war was over.

As farmer uprisings and antigovernment movements stoked fears that another revolution could spark a second civil war, domain leaders embarked on major military reforms. Notably, in Kishū (now Wakayama Prefecture), Tokugawa Mochitsugu hired Tsuda Izuru, who set out to remake the domain’s military forces into a Prussian-style army, signing up a Prussian officer called Carl Cöppen as an advisor. By early 1870, Kishū had disbanded its regular army and introduced a conscription system. This was three years earlier than the Meiji government. The domain had a standing army of 7,000 men, with around the same number of reserves, and they were armed with the latest Dreyse needle guns.

The new government was also concerned by developments in Satsuma (now Kagoshima Prefecture). Shimazu Hisamitsu—the father of the domain governor Tadayoshi, and the actual wielder of power there—was opposed to the central government’s reforms, while Saigō Takamori, who had fought with the Meiji forces in the Boshin Civil War, continued to push forward with strengthening of the Satsuma military.

A National Standing Army

Ōkubo Toshimichi of the Meiji government traveled to Satsuma in the spring of 1870 to call Hisamitsu and Saigō to Tokyo. Hisamitsu rebuked Ōkubo and denounced the government, while Saigō also refused to make the journey to the capital. Then Ōkubo and Kido Takayoshi requested Emperor Meiji to officially summon the reluctant pair, and in early 1871, they went to Satsuma with the imperial envoy Iwakura Tomomi. Hisamitsu pleaded illness as a reason he could not immediately travel to Tokyo, but Saigō agreed, if he was entrusted with reforms.

Part of the plan Saigō submitted was that the architects of the Meiji Restoration—Satsuma, Chōshū (now Yamaguchi Prefecture), and Tosa (now Kōchi Prefecture)—would supply soldiers to establish a national standing army. The historian Katsuta Masaharu suggests that he made the proposal because Satsuma’s large army was a burden on domain finances, and he wanted the national government to shoulder some of the costs. In any case, the plan was accepted in the spring of 1871, and 8,000 soldiers from the three domains assembled in Tokyo by the summer. With these forces in place, the stage was set for announcing the replacement of the domains with new prefectures on August 29, 1871.

The movement had actually begun in earnest two years earlier with requests from small domains that could not afford to pay stipends to retainers. Some larger domains like Tottori, Owari (now Aichi Prefecture), Kumamoto, and Tokushima also requested abolition, so as to achieve a unified state. Within the government, Ōkuma Shigenobu advocated that the central government should dispatch officials to each domain for political unity. Four months before the domains were officially abolished, Etō Shinpei made a proposal that was almost the same as the plan ultimately adopted.

A Power Grab

Thus, the country was ready for the change, but it was the Satsuma-Chōshū faction that made abolition of the domains actually happen. A small number of high officials effected what was essentially a coup d’état. Nomura Yasushi and Torio Koyata, two midlevel officials from Chōshū with knowledge of military affairs, set the ball rolling in the middle of August 1871 by convincing the statesman Yamagata Aritomo to back their plan. Next, on August 20, the group got Inoue Kaoru on its side—as he was in charge of the government’s financial affairs, he saw the economic necessity of abolishing the domains, and agreed to persuade the Chōshū leader Kido Takayoshi. The following day, Kido immediately gave his approval. A diary entry from three years earlier shows that he was in favor of the move, for the purpose of unifying the nation.

The biggest remaining hurdle was to sway Saigō Takamori, who controlled the Satsuma samurai. This task fell to Yamagata. When he broached the subject, Saigō said, “That is acceptable, I think,” before asking, “What’s Kido’s opinion?” It was such a simple assent that Yamagata asked, “First I want to know your opinion.” Again, Saigō said, “That is acceptable.” Taken aback, Yamagata said, “You understand that removing the domains will likely lead to bloody uproar.” Saigō responded, “I accept that.” At this moment, Yamagata realized everything was in place.

Why did Saigō agree, when it meant the end of Satsuma? Researcher Matsuo Masahito has written that Saigō himself probably realized that the feudal territorial system was reaching its limit. No matter what reforms the Satsuma domain carried out, there were only so many soldiers it could support. Providing soldiers to the government meant the burden was passed on, but led naturally on to an unavoidable transformation in the territorial system itself.

An Imperial Rescript

Kido was delighted to hear of Saigō’s agreement. On August 23, the two men met directly to hammer out the details. Saigō had already won Ōkubo’s consent, and on August 24, Kido, Saigō, and Ōkubo—considered the three leading figures of the Meiji Restoration—, together with Satsuma figures like Ōyama Iwao and Saigō Jūdō, and Chōshū representatives such as Inoue Kaoru and Yamagata Aritomo got together for discussion. Nonetheless, as Kido wrote in his diary for August 25, planning continued in absolute secrecy.

Major government members like Sanjō Sanetomi and Iwakura Tomomi did not even know about the plan until August 27, two days before it was set to go ahead. Although thrown off balance, they had no alternative but to support it. Thus, on the morning of August 29, the governors of Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Hizen (now Saga Prefecture) and other representatives were called to the imperial court, where they were informed of the abolition of their domains through an imperial rescript by Emperor Meiji. The same message was conveyed to the governors of Tottori, Owari, Kumamoto, and Tokushima, who had previously requested abolition. That afternoon, 56 other governors who were in Tokyo were also summoned and told of the change. At this moment, the feudal system of domains, which had continued for around seven centuries, came to an end.

The imperial prescript abolishing domains and establishing the prefectural system. (Courtesy of the National Archives of Japan)

Governors were dismissed from their posts and ordered to reside in Tokyo, while the central government dispatched its own officials to oversee the newly established prefectures. While the time was ripe for general acceptance of the change, the coup planners were ready for the possibility of enraged samurai taking up arms at the loss of their traditional masters. Saigō declared to other leading government officials, “If any domains object, we’ll crush them with military force.”

Yet there was no opposition. This was partly because the sudden nature of the action dampened the fervor for rebellion, with the sense that the moment had passed. The biggest reason, however, was probably that the Meiji government took on domain debts and promised to pay samurai stipends.

Consolidating the Prefectures

The government had successfully unified the state, but as it was the Satsuma-Chōshū faction that drove the action forward, it won a disproportionate power within the government. In this sense, the abolition of the domains could be said to represent the seizure of power by this faction.

The announcement did not mean that the central government immediately took control of prefectural administration. Following the abolition of the 261 domains and replacement by prefectures, there were 305 altogether, including former shogunate territories, of which 3 were the fu (urban prefectures) of Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto. The Ministry of Finance, headed by Ōkubo, oversaw the administrative work involved in the transformation. As each prefecture varied greatly in area, the ministry planned reforms to set them at around the same scale, based on rice production of around 300,000 to 400,000 koku (a unit equivalent to around 180 liters of rice). This was thought to be the right size for regional administration. There was even a proposal to divide Chōshū into two smaller prefectures. By December, the plan for 75 prefectures—plus the new territory of Hokkaidō—was largely settled.

Only 13 prefectures retained the same names. Katsuta Masaharu says that by changing the names, the government sought to cut ties with the former domains. Instead, the names of, for example, towns and villages or rivers and mountains were chosen for the prefectures. The same reason was behind the decision to send people born in other domains to serve as the new governors. However, in prefectures that were prominent in the civil war—such as Kagoshima, Kōchi, and Saga—local leaders were appointed, presumably due to their influence in the central government.

After this, Okinawa was made a prefecture in 1879, while in 1882 the territory of Hokkaidō was split into the three prefectures of Sapporo, Hakodate, and Nemuro. Considerable reorganization of the other prefectures also continued through these years until 1888, when there were the same 47 as today.

The 1871 abolition of the domains and establishment of the prefectures gave the new government the unified power to conduct wide-ranging reforms in taxation, the military, and education. These in turn allowed Japan to industrialize and build up its economic and military strength.

| March 1869 | The leaders of Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Hizen petition to return domain registers (territory and citizens) to the state. Later, other domain leaders make their own petitions. |

| June 1869 | The Boshin Civil War ends with the victory of the Meiji forces and the defeat of the shogunate. |

| July 1869 | The domains return their registers to the state and the daimyō are appointed as governors. |

| August 1869 | The Kaitakushi (Hokkaidō Development Commission) is established. |

| September 1869 | The territory of Ezochi is renamed as Hokkaidō. |

| Early 1870 | Some domain leaders start to petition for the abolition of the domains. |

| Summer 1870 | Political debates over the domain system begin in the legislature. |

| Early 1871 | Iwakura Tomomi’s group travels to Satsuma.Saigō Takamori submits reform proposals. |

| April 1871 | National army formed including soldiers from Satsuma, Chōshū, and Tosa. |

| August 1871 | Feudal domains abolished and prefectural system established with 305 prefectures. |

| January 1872 | Consolidation into 75 prefectures. |

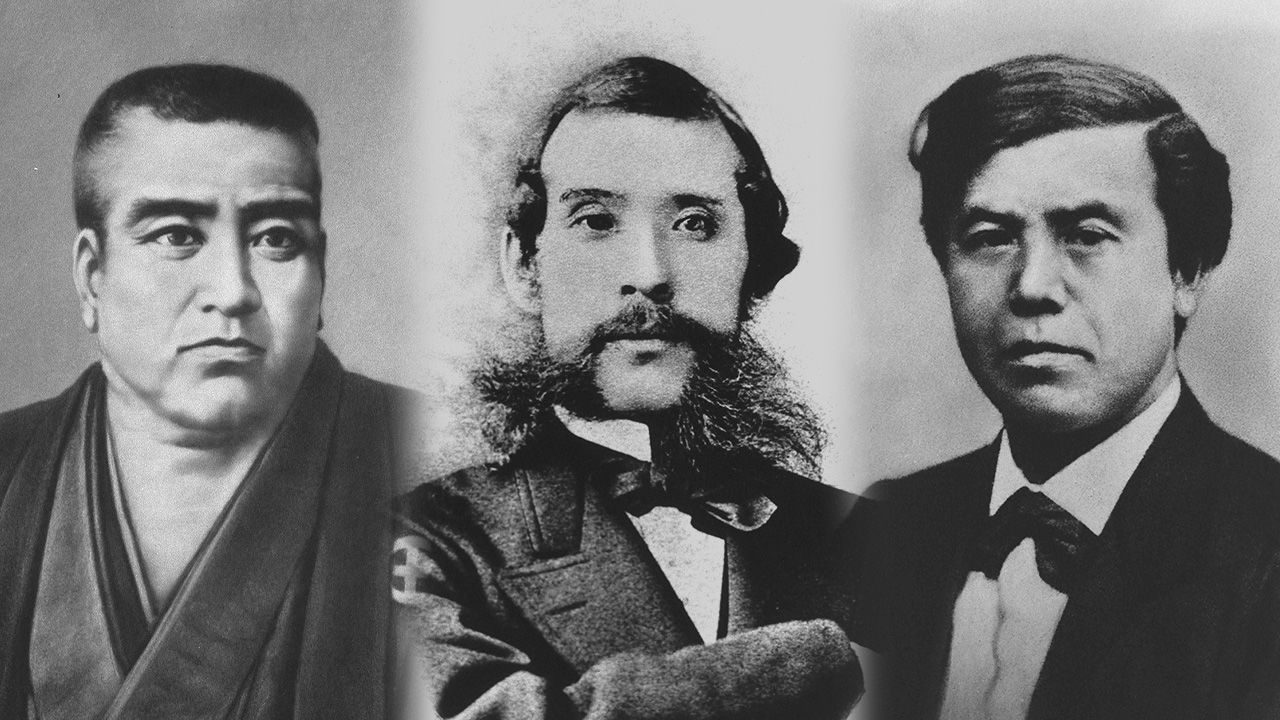

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photos: Saigō Takamori, Ōkubo Toshimichi, and Kido Takayoshi, who are considered the three leading figures of the Meiji Restoration. Courtesy of the National Diet Library.)