The Cycle of Life Through the Lens of the Tokyo Olympics

Tokyo 2020 Society Economy Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Defeated Japan Joins the Ranks of Advanced Nations

At the time of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, I was 27. I had graduated from university just two years earlier and was working as a journalist for a news agency. At university, my generation was the first to engage in conflict over efforts to establish the US-Japan Security Treaty. In protests at the National Diet Building in Tokyo, I was jostling with police when the student activist Kanba Michiko died in clashes nearby.

After the conflict subsided, the world seemed completely different, like a new page had turned. The era of the 1957–60 Kishi Nobusuke administration was dominated by debate over remilitarization, while that of Ikeda Hayato (1960–64) focused on the economy, under the policy of a 10-year plan to double the nation’s average income. Procurement orders placed by the US military for the Korean and Vietnam wars contributed to the economy, which was about to shift into a high-growth phase.

For my first journalistic assignment, I was posted to the press club of what was then the Ministry of Finance. The minister was Tanaka Kakuei, who developed the engine of Ikeda’s income-doubling plan in both fiscal and monetary terms, earning him the nickname “the computerized bulldozer.” Tanaka’s fiscal policy was to significantly increase spending based on natural revenue growth in taxes, forcing the usually prudent Bank of Japan to ease monetary policy to questionable levels.

In just over a decade since defeat in the war, Japan had turned around its fortunes and embarked on a path that prioritized the economy. In 1959, Crown Prince Akihito and Michiko were married, which, together with the 1964 Olympics, seemed to inaugurate this era. Japan also gained membership of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in 1964, cementing its place among the world’s advanced nations. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank annual meetings were held in Tokyo, the first time for them to take place in Asia. Japan, which had been a member of the IMF since 1952, acceded to the more stringent obligations of the organization’s Article VIII in 1964, adopting exchange rate policies akin to those of developed countries; this increased the value of the currency.

Aside from such policy and systemic decisions, in 1965, Osaka was chosen as the host for the 1970 World Exposition. Major infrastructure was developed: The Tōkaidō Shinkansen opened in 1964, and the Meishin Expressway, Japan’s first expressway, opened in sections between Nagoya and Kōbe starting in 1963.

Down-Time Ping-Pong

From the Ministry of Finance press club, I reported on Japan’s postwar high-growth phase from the time of the Ikeda administration through to that of Satō Eisaku (1964–72), focusing on finance, but I also reported on the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. It was all hands on deck to cover the event, and despite being in the economic bureau, I was recruited as a reserve for the city news section. Having majored in French at university, I was assigned to cover athletes and visitors from French-speaking countries, and to gather tidbits and miscellaneous impressions.

Our reporting base was Akasaka Palace State Guest House, unused since the war, converted into offices for the Japanese Olympic Committee. Initially, the entire building was vacant. Interviewing foreign athletes required an introduction from a JOC representative. There were two ping-pong tables in the waiting room for journalists, and we often played to while away the time. Such tranquility amid the bustle symbolizes that era.

I have described my time reporting on the Olympics as a serious venture, but I was actually only involved in the lead-up to the opening ceremony. Well before the event, I had applied and received approval for a week-long vacation starting from the date of the ceremony. My reason was purely personal: I was to be wed that day.

Two years into my career as a newspaper reporter, when it was starting to become interesting, I had resolved to dedicate my life to journalism. I was determined to settle down, after many carefree years of young love with my college sweetheart. The opening of the Olympics was the perfect opportunity, because it mainly involved the sports and city desks. By my reckoning, the economic bureau would be quiet.

I was repatriated from Japan’s former colony in Manchuria after the war, in the fall of 1946, but I was still naive about Japanese ways. Although I was born here, I grew up moving from place to place in northern Korea and Manchuria due to my father’s work, and as a child, Japan was foreign to me. I was enchanted the first time I set eyes on the autumn colors and tasted the sweetness of the persimmon grown “back home” in the Miyagi Prefecture capital of Sendai.

Lessons from the Big City

When I first experienced Japan’s scenery and customs, everything was a novelty. With the curiosity and wanderlust I had acquired on the continent, I wanted to see it all, to know and try everything. My grandfather was a journalist and my father did fieldwork as a linguist and folklorist, so it was in my DNA to become embark upon journalism.

I left home for Tokyo to enter university in 1956, boarding in a known red-light district in Yokohama and teaching part-time at a cram school. My student days, as Japan recovered from defeat to economic expansion, set the stage for my coverage of Japan’s economy. My side-job, student activism, and courtship of my future wife all provided extracurricular experience.

Actually, the precursor to this was my bitter experience in the year and a half I lived as a refugee in Andong (now Dandong in China’s Liaoning Province), when I even roamed the black market selling cigarettes, before my repatriation. I spent this formative time in the postwar chaos of that port city, witnessing theft, violence, murder, drug dealing, and prostitution.

My family was impoverished, and I could only move to Tokyo with the help of an uncle in Yokohama. I was at university for five years, including a year I repeated, and only got by through my tutoring work. I became the private tutor for a girl from the cram school, but when I was hired by Jiji Press, I convinced her to quit her studies and promised to marry her.

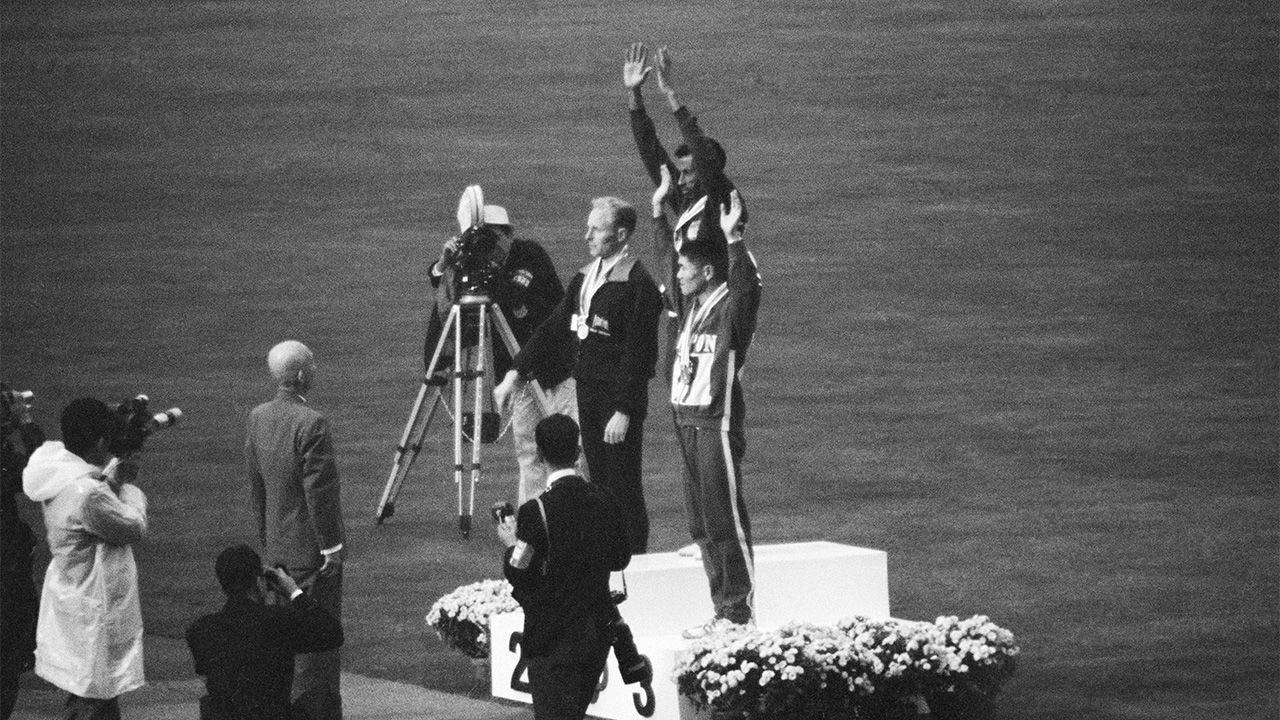

I still clearly remember the Tokyo Olympics. We watched it on NHK throughout our honeymoon. I can still recall the gymnasts Ono Takashi and Endō Yukio from Japan and Věra Čáslavská from Czechoslovakia, the women’s volleyball team led by their tough coach “Demon Daimatsu” Hirofumi, the weightlifter Miyake Yoshinobu, the jūdōka Inokuma Isao, and Ethiopia’s Abebe Bikila, who won his second Olympic marathon after famously running barefoot in Rome in 1960. I also recall Tsuburaya Kōkichi, who won bronze in the men’s marathon, but tragically took his own life before the subsequent Mexico Olympics. The camera work of film director Ichikawa Kon and the Olympic March, composed by Koseki Yūji—I remember it all so vividly.

Paling in Comparison

These images came to symbolize the prosperity of the high growth Japan that I mentioned earlier. Eventually, this gave way to the overheated bubble economy of the late 1980s and its subsequent collapse. From the excessive pride that led Japan into a reckless conflict, the repentance that followed our defeat, the renouncement of war, and the subsequent one-eyed pursuit of money, our nation saw its image distorted. By the time we realized that true happiness lay in improved culture and lifestyle, it was already too late.

Although the Olympics are staged every four years in principle, the aspirations of modern politicians such as Ishihara Shintarō, Abe Shinzō, and Suga Yoshihide to “relive the dream” and leverage the Games for political purposes were stopped in their tracks by COVID-19: a moral lesson for one and all. Now that the banquet is over, I can see it clearly: While the 2020 Games were the same event, carried out to the same tune, the 1964 Games shone brightly owing to the era. This year’s event paled in comparison, and failed to make a mark. In contrast, the 2020 Paralympic Games (which were also held 57 years ago) left a deeper impression on us this time around—perhaps reflecting our keener appreciation, as an elderly couple, of the need for a solid social welfare system.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Bronze medalist Tsuburaya Kōkichi raises his hand to the crowd along with the marathon winner, Ethiopia’s Abebe Bikila, as Britain’s silver medalist Basil Heatley looks on, at the award ceremony at the Tokyo Olympic Stadium on October 21, 1964. © Jiji.)