Maternal and Child Health Handbooks: From Japan to the World

Society Health Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Overseas Debut in Indonesia

Japan’s use of boshi techō, or Maternal and Child Health Handbooks, began in 1948, not long after the end of World War II. These small notebooks keep extensive records, starting with a pregnancy record, the mother and child’s conditions at birth, and the child’s health from the time of the birth until elementary school. They have helped protect the lives of many mothers and their children, enabling them to grow up healthy.

“As a pediatrician in Japan for many years, the boshi techō was simply a given for me. Yet, when I went to work in Indonesia, I found there were no organized records for mothers and children,” says pediatrician and director of the Friends of WHO Japan, Nakamura Yasuhide. Nakamura went to the Indonesian island of Sumatra in 1986 as a specialist with the JICA North Sumatra Health Promotion Project. At the time, he says, many Sumatran mothers were losing their lives in childbirth, and many children failed to survive to their fifth birthday.

“There were records of the child’s weight at birth and of vaccinations, but they were flimsy paper cards folded in thirds. Many mothers simply didn’t have them because they were lost or water damaged. And in Indonesia, vaccinations end after the first year of age, so very few people kept those cards after that. That was when I realized just how wonderful Japan’s boshi techō really are.”

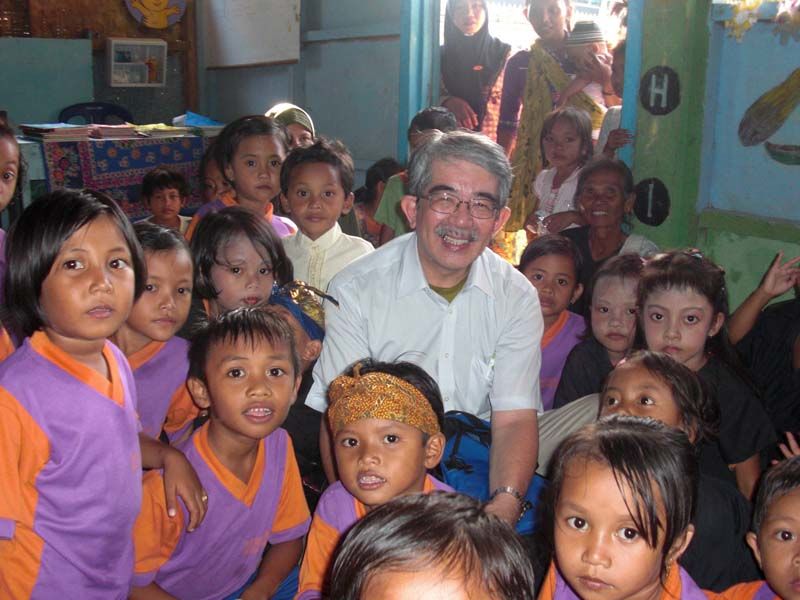

Nakamura surrounded by nursery school children on the Indonesian island of Lombok.

Nakamura took it upon himself to investigate Japan’s medical history, and discovered that Japan’s child mortality rate had started declining even before it adopted advanced medical care.

“One of the international Sustainable Development Goals is to reduce infant mortality numbers to twelve or fewer per thousand live births by 2030, and Japan achieved that more than fifty years ago. At a time before ventilators and when incubators were barely sufficient, we took care of the basic needs of the babies: keeping them warm, giving them a little water and nutrition, and keeping them clean so they wouldn’t get sick. I feel that beyond the hard work of doctors and nurses, Japan’s low infant mortality rate was achieved in large part due to the existence of the boshi techō.”

Surprises Offered by Japan’s Infant Health Care

After two years and three months of service, Nakamura returned to Japan, and in the winter of 1992 invited two Indonesian doctors to visit him there. They traveled around the country observing infant health checkups as training. They were surprised to find that wherever they went, mothers brought their boshi techō, and healthcare workers and doctors always recorded the exam results.

The doctors both insisted that they wanted to take the boshi techō practice back to Indonesia. Nakamura recollects, “I was glad to see their fervor, but I had to point out that there could be some roadblocks to the plan.”

They could not simply print up and distribute handbooks. The contents had to be understandable not only to doctors and nurses, but mothers and fathers as well. It would also require training for the system to take root, and the road to widespread adoption would likely be difficult.

Nakamura says, however, that the doctors stood strong. “They said, ‘We are still going to do it. Because we already have a prototype back home!’ and then they took out a booklet of yellow paper.”

It was a handmade maternal and child health handbook that Nakamura had made himself with local doctors during his time in Indonesia. He recalls: “I was surprised that this thing I’d made had come back to me in Japan, and happy, as well.”

The Indonesian maternal and child health handbook project started in earnest soon after.

Nakamura (second from left) with health volunteers in North Sumatra, Indonesia.

The first issue was deciding which region to start in. If the population was too low, it would be hard to judge the results, but starting in a big city would require much more labor and investment.

They eventually settled on the city of Salatiga in Central Java Province, which then had a population of 150,000. It has a university and hospitals, and a relatively high educational level among young people.

They calculated the number of maternal and child health handbooks needed for a year based on the population and birthrate, and prepared a few more. And yet, soon after they began distribution, they received word that stock was running out.

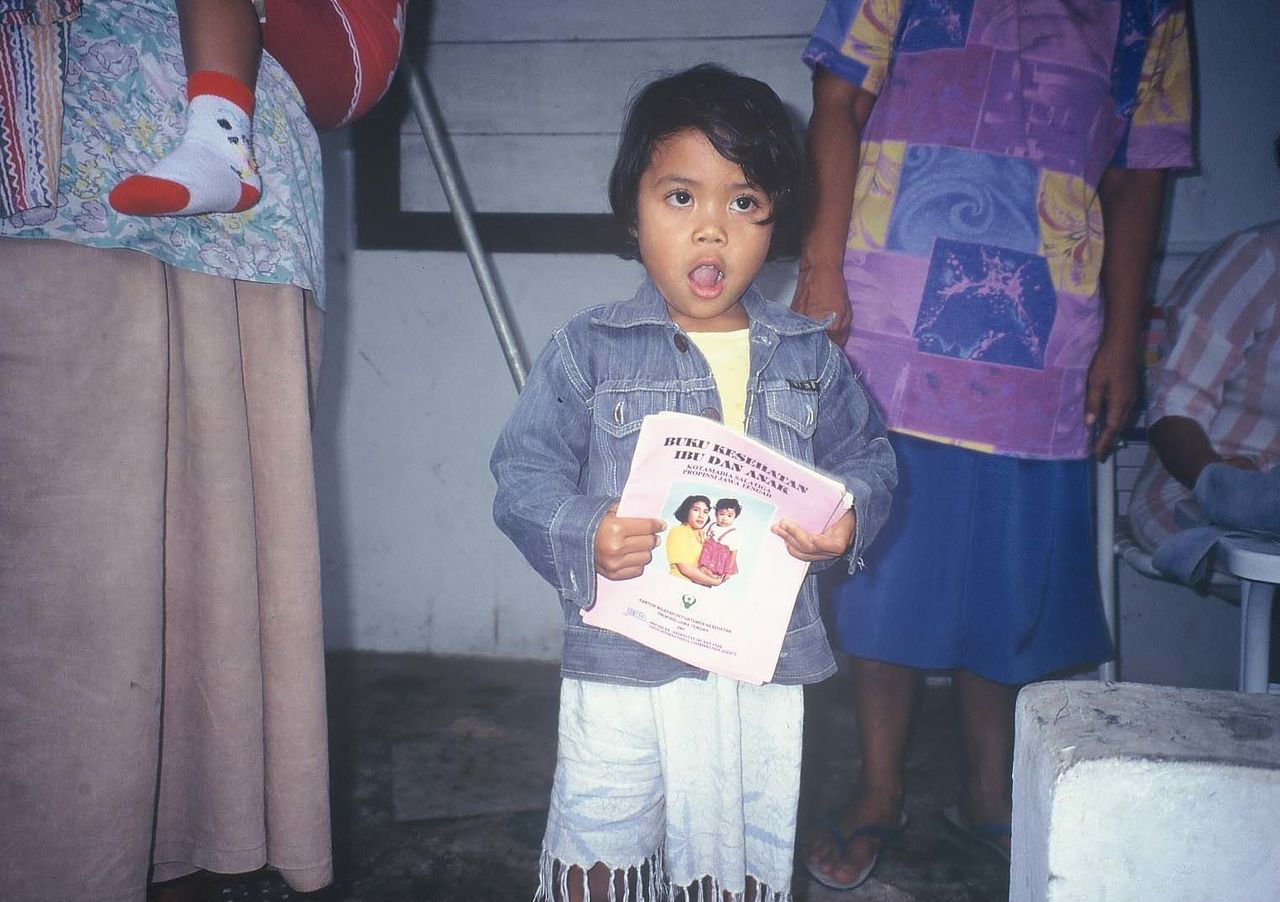

“We thought that it was impossible, but when we went out to check, we found that mothers from the nearby areas were coming to get them. When we asked some why they had come, they said they’d heard that something good was being handed out. The network of mothers was really something, and was spreading information far faster than the government could. And then, showing one reason why I love Indonesia, the healthcare center workers didn’t say ‘You’re from another town, you can’t have one.’ Instead they said, ‘Welcome!’ and handed them out. So, of course they ran out!”

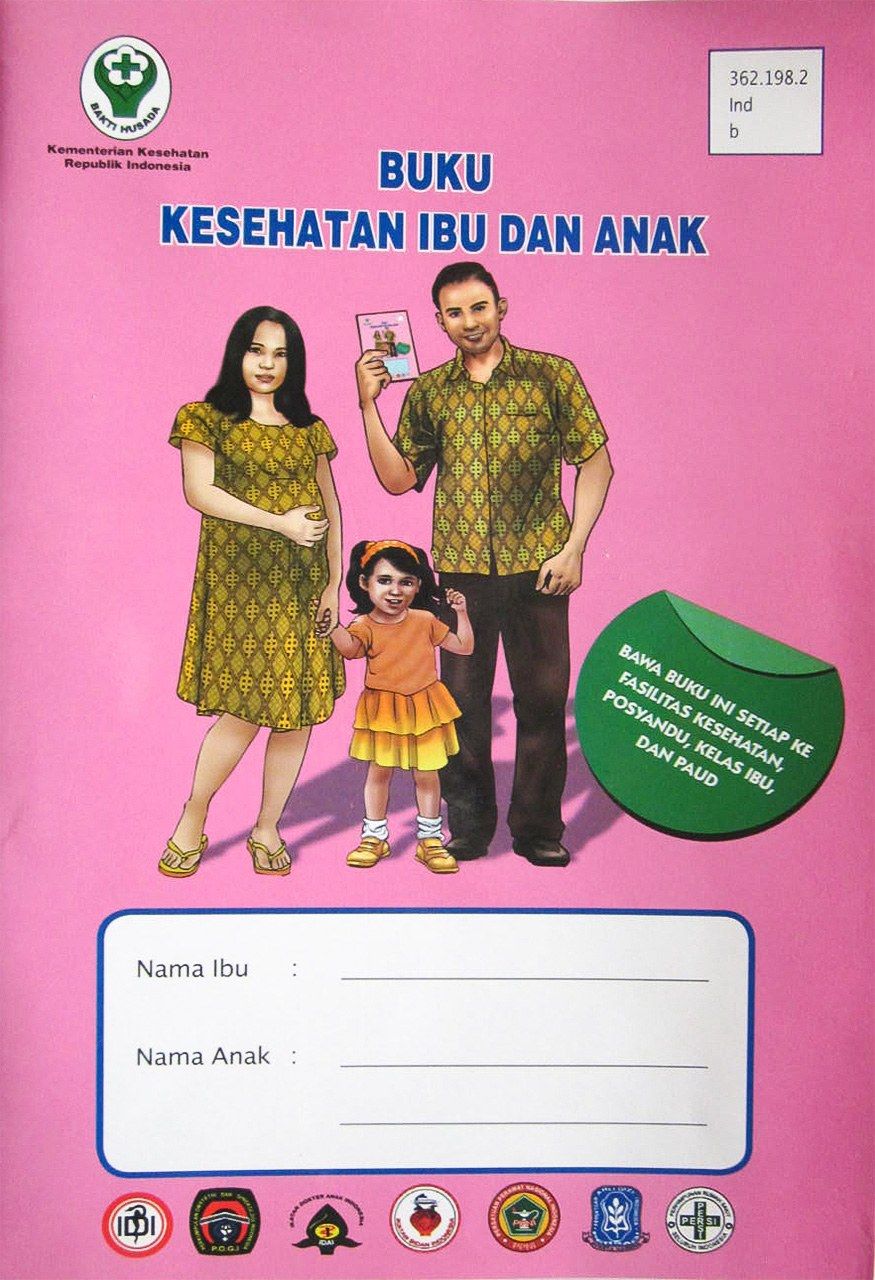

The cover of an Indonesian maternal and child health handbook.

More Illustrations for Nations with Low Literacy

Another barrier was dealing with nations with lower literacy rates than Japan. The handbooks do more than keep health records, also offering guidance on pregnancy and infant-raising needs. So, the team added lots of illustrations so that mothers could understand the content even without reading.

“We didn’t simply translate Japan’s boshi techō into their languages. Japan and Indonesia have their own cultures and medical systems, so we made sure that the cards and such that everyone already used could be slipped into the handbooks for safekeeping.”

A child in central Indonesia holding her handbook.

They have followed this same approach not only throughout Indonesia, but in other countries, as well. Now, roughly 50 countries, mostly in Asia and Africa, have adopted the handbook system. They are customized to the situations of each country, and parents use them with great care.

Nakamura says that when things spread overseas, the perspective back home changes, as well.

“Boshi techō appeared in Japan right after World War II, so even if someone asked me what good they did, I couldn’t have answered. Measuring results would require comparing groups that have them with groups that don’t. And in Japan, now, we couldn’t tell someone, ‘Please join this group of people who don’t have boshi techō.’ The results only came clear when we compared the situation in countries newly adopting them before and after adoption. That’s a huge benefit for Japan.”

New Approaches for Japan to Emulate

One thing Japan should learn from other countries is digitalization, says Nakamura. In Vietnam and other countries, QR codes were included on the handbook covers very early on, allowing users to transfer the data to their smartphones by scanning the code.

“I think that’s very handy. Mothers today always carry their smartphones, letting them check the records anytime, anywhere. However, there is some benefit in having the printed handbooks, so I’m against complete digitalization,” Nakamura notes.

Rawan Hussein, a Palestinian living in a refugee camp, holds a paper maternal and child health handbook and a smartphone with a companion app, at a United Nations Relief and Works Agency clinic in Amman, Jordan, on April 4, 2017. Refugees have taken to calling the handbooks “life passports.” (© Jiji)

Nakamura then shared this anecdote.

“At a certain high school in Japan, there was a lesson using boshi techō. The students opened their own childhood handbooks and listened to a midwife’s explanation. They saw their mothers’ dated notes saying things like “Stood for the first time. So happy!’ or “Walked!’ One girl, who had been in a rebellious phase, saw those notes and said ‘When I get home today, I’m going to tell my mom thanks.’ I was floored, and realized what a treasure they are for families.”

From “Mother and Child” to “Parent and Child?”

The first handbooks issued in 1948 were officially called Boshi techō (Mother and Child Handbooks); in 1966, the name was officially updated to Boshi kenkō techō (Maternal and Child Health Handbook). No matter how the world changes, though, the joy of a new mother learning she is pregnant does not.

The handbooks are all made by local governments, and more and more are changing the name to Oyako kenkō techō (Parent-Child Health Handbook) because the term “mother and child” is growing less appropriate as men participate more actively in childcare.

“When we introduced the handbooks abroad, we first proposed the name as Parent and Child Handbooks, rather than Mother and Child, but many countries say they prefer to keep it as mother and children. One time in Africa, something related to that was particularly convincing.”

The ninth annual International Conference on the Maternal Child Health Handbook took place in Cameroon in 2015. Eight Cameroonian government ministers, including the minister of health, attended the opening ceremony. Curious, Nakamura asked the minister of agriculture and forestry, a woman, sitting next to him why she was there.

She replied, “I am the first woman to serve as Minister of Agriculture in my nation, and I want to solve the problems that women farmers suffer. However, women on farms often give birth at home, and it’s common for them to get ill or die from it. My wish is for women to be able to return to farming in good health after pregnancy and childbirth. So I’m very much in favor of and very interested this handbook to protect mothers and children.”

“I understood her,” says Nakamura. “In this country, the handbooks are something to protect the lives of mothers and children. When you open the books, you see illustrations of men on nearly every page. There is a big X over a picture of a man smoking, or a drawing of a man taking care of his child. The title is Maternal and Child Health Handbook, but it still helps to raise awareness that women are not the only ones who raise children. I really felt like the handbook has a deeper meaning.”

A Cameroonian version of the handbook.

Even now, Nakamura is helping to spread the handbooks around the world. In 2018, the World Medical Association announced that medical associations around the world should make greater use of the handbooks. Nakamura hopes that will encourage more countries to roll them out.

Handbooks from around the world.

“Just a few years ago, I went back to visit Salatiga, the city where we first distributed boshi techō in Indonesia. I happened to mention the handbooks to a taxi driver, and he said his family had one at home. So, I asked him if I could visit his house. His wife showed off their handbook with pride, explaining it just like a medical worker, saying ‘This page is for during pregnancy, and this is for the birth record.’ The last thing she said was, ‘Do you have anything like this in Japan?’ It felt like the greatest compliment I’ve ever gotten.”

Nakamura listening to a handbook explanation in East Timor.

Umi o watatta boshi techō (Maternal and Child Health Handbooks Across the Sea)

By Nakamura Yasuhide

Published by Junpōsha (in Japanese) in August 2021

ISBN: 978-4-8451-1708-6

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A pregnant woman, accompanied by her partner, bringing her maternal and child health handbook to a health checkup in Bali, Indonesia. All photos © Nakamura Yasuhide except where noted.)

children Parents mother boshi techō Maternal and Child Health handbook child