Girl’s Manga Pioneer Mizuno Hideko: Her Message for the Modern Day

People Culture Art Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Inspired by Tezuka’s Manga University

Mizuno was born in the fishing port city of Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Her father had been stationed in Japan’s overseas colony of Manchuria during World War II, but never returned home after the confusion at the end of the war, and so Mizuno grew up without a father at her mother’s family home. Her mother also died young, so her family was reduced to her grandmother and one uncle, whom she called Big Brother. There was a book rental shop not far from their house, and from a young age she fell under the spell of a collection of world literature aimed at young readers she found there. She also recollects, “Big Brother liked movies, so he took me with him to watch westerns and Tarzan movies.”

At that time, manga’s mainstream form was single-volume books written for these rental shops, or paid “lending libraries,” and magazines were in the heyday of picture stories for boys. The most popular stories were adventures like Shōnen Keniya (Kenya Boy) or Sabaku no maō (Demon Lord of the Desert), as well as war stories and westerns. Then, when she was around 11 years old, she had a fateful encounter with Tezuka Osamu’s Manga daigaku (Manga University), a book published in 1950. It mainly focused on teaching readers how to draw manga for themselves, but it also included a few short stories.

“The stories weren’t simple ones of good versus evil. They had deep messages and insights into human nature that were almost shocking. He drew all kinds of genres, like western, mystery, fairy tales, and even sci-fi. His science fiction outing in that book ended with warnings for the future. In those days, there were no other artists making stories like that for children to read.”

Mizuno had been drawing and writing her own stories from a very young age, and in that moment she decided that she would become a manga artist herself. “I used a pen to practice in fifth and sixth grades, and when I got to junior high school, I started submitting to Manga shōnen, the only place that accepted amateur submissions in those days. Tezuka was the judge. Winning entries got published, but mine were always honorable mentions.”

Moving into Tokiwa-sō at 18

Her debut came about through a lucky coincidence. Maruyama Akira, the editor in charge of handling Tezuka’s serial Ribon no kishi (Princess Knight) for the monthly magazine Shōjo kurabu (Girl’s Club), happened to stumble on one of Mizuno’s submissions when he went to pick up a manuscript. “I don’t know what my manuscript was doing there. But Tezuka apparently said that I could draw pretty cute pictures, so why not try to train me up.”

Around when she graduated from junior high, Maruyama sent a letter asking her to put together a small piece for him, and soon she took her first step on the way to becoming a pro manga artist. For a time, she went on working at a local fishing net factory while she drew. Her first long-form work was a western about two young girls and a horse.

In March 1958, at the age of 18, she went to Tokyo and spent seven months in the Tokiwa-sō boarding house, a location that would become famous for hosting the future masters of manga in their youth. Her main work then was an experimental collaboration with Ishinomori Shōtarō and Akatsuka Fujio. Ishinomori would put together a storyboard, Mizuno was in charge of the characters, and Akatsuka put them all together. “On my third day in Tokyo, Ishinomori took us to see The Ten Commandments at a Ginza movie theater. From then on, whenever we had time, the three of us would go see movies together.”

A re-creation of Mizuno’s room at the Tokiwa-sō Manga Museum. (© Nippon.com)

“Ishinomori also liked music, and he collected all kinds of records, from classical to pop, jazz, and even movie soundtracks. I was into classical as well because of NHK’s radio broadcasts, so I really enjoyed music, too. We sat drawing our manga like mad in Ishinomori’s room, surrounded by piles of records and books.”

Tokiwa-sō became the starting point for shōjo manga, works aimed specifically at a young female audience, says Mizuno.

“At the time, the mainstream for boys was still picture stories, and the action-driven narratives of shōnen manga still hadn’t fully developed. Shōjo manga magazines were just starting out, and there weren’t enough artists to draw them. And so Ishinomori, Akatsuka, and all the young people at Tokiwa-sō were drawing shōjo manga. Each of us had been immensely influenced by Tezuka, and we experimented with all kinds of things. As the years went on, shōnen manga started to move beyond simple narratives and into more complex work because of the groundwork done in shōjo manga.”

The First Shōjo Manga Romance and Epic Historical Drama

Mizuno’s 1960 Hoshi no tategoto (Harp of the Stars) broke shōjo magazine taboos by bringing the first romance to the genre. It is a story with a powerful setting based on Wagner’s Die Walküre, the second part of his opera Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Hoshi no tategoto (Harp of the Stars), left, and Shiroi toroika (White Troika).

“In our school days, boys and girls played apart even though we attended the same school. I thought it was strange that we couldn’t be closer, despite our interest in each other. Even marriage was all about arrangements, not love. All of the world’s great stories and movies show beautiful romance. So, I thought it would be good to do the same in manga.”

Her later work Shiroi toroika (White Troika), published from 1964 to 1965, is set against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution and is shōjo manga’s first historical drama.

“I was a fan of myths and legends from my junior high days, and was in love with the epic story and music of Der Ring des Nibelungen. And I was also very interested in Russia. I read Big Brother’s Russian literature, and went to see Russian movies. Above all, just like Tezuka, I wanted to do work in all kinds of dramatic styles and at all kinds of scales.” Mizuno’s creative inspirations, then, are the work of Tezuka, world literature, music, and movies.

Exploring the Wild World of Rock

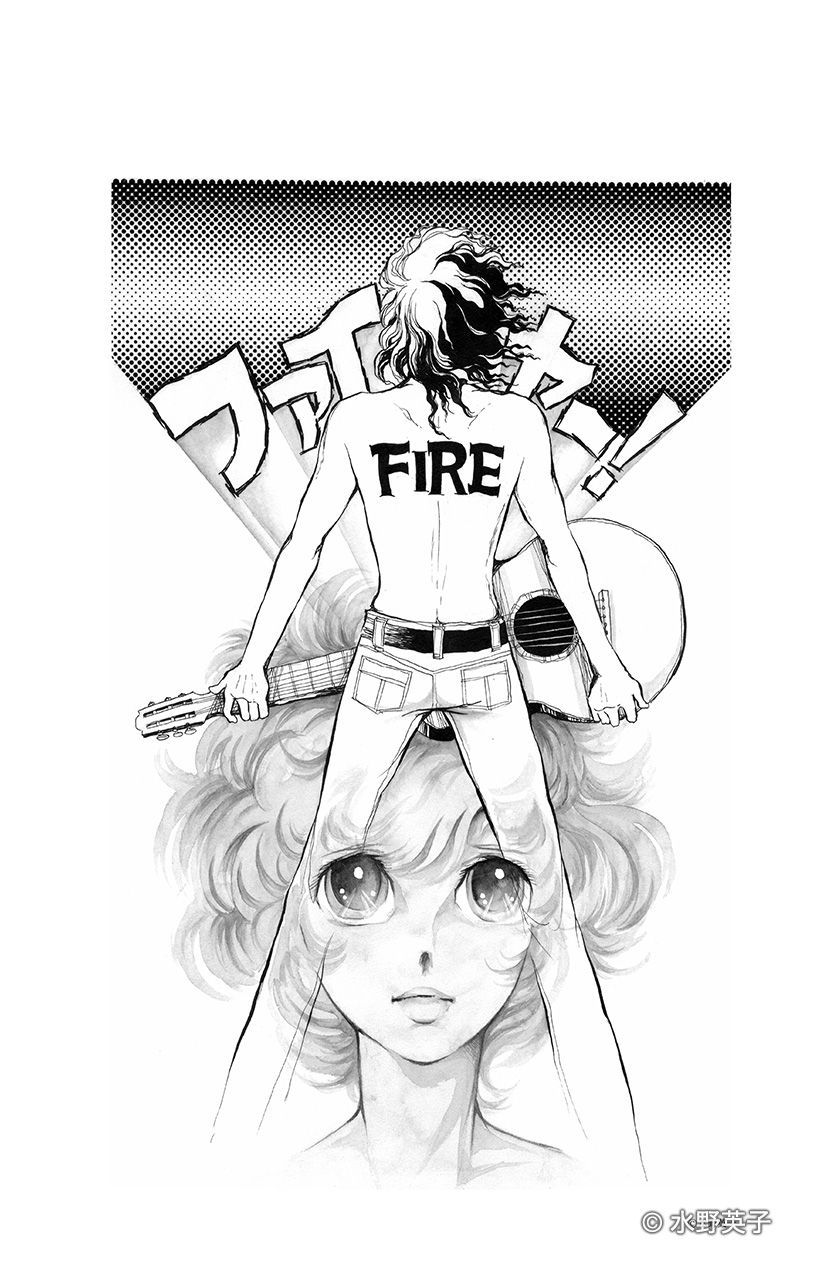

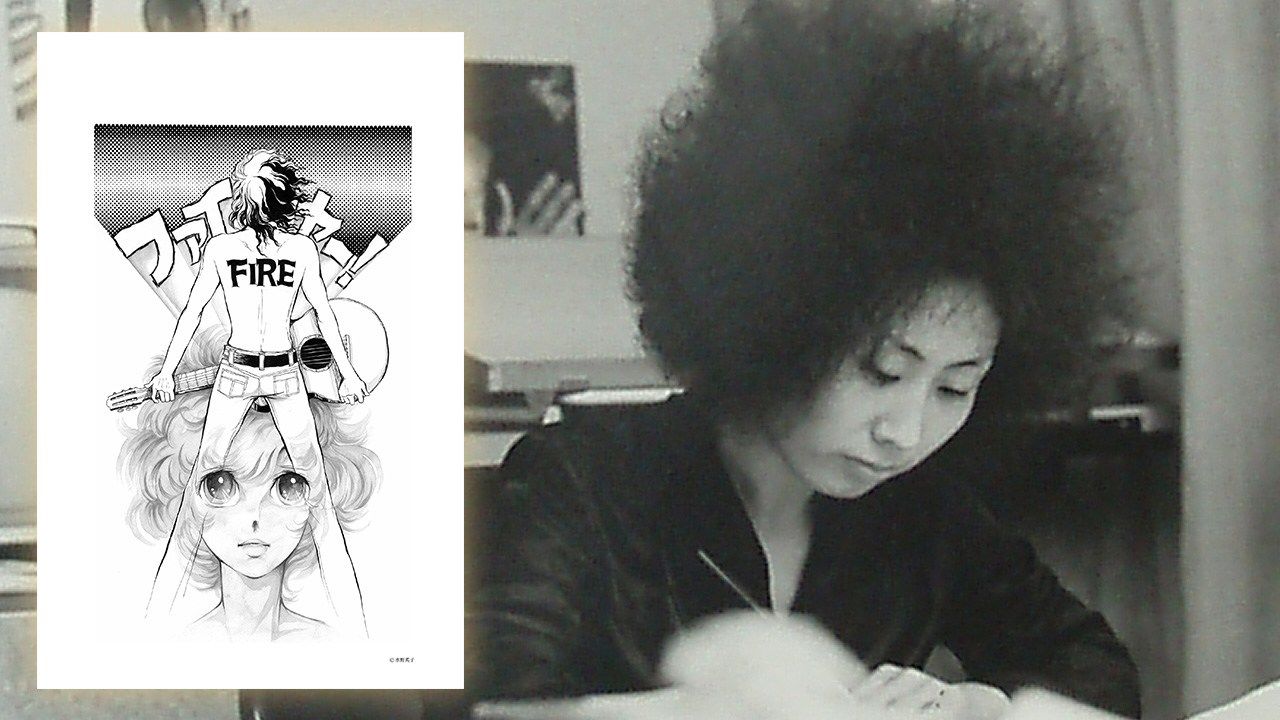

She calls herself a “heretic” for taking on ambitious themes and depictions in her work. Her heresy reached its pinnacle with 1969’s Faiyā! (Fire!), serialized in Shūkan sebuntīn (Weekly Seventeen). It was a groundbreaking work that went beyond the traditional framework of “girl’s stories” and projected the spirit of the age of rock from the days of the anti–Vietnam War movement and civil rights protests in the United States, a time of great turbulence.

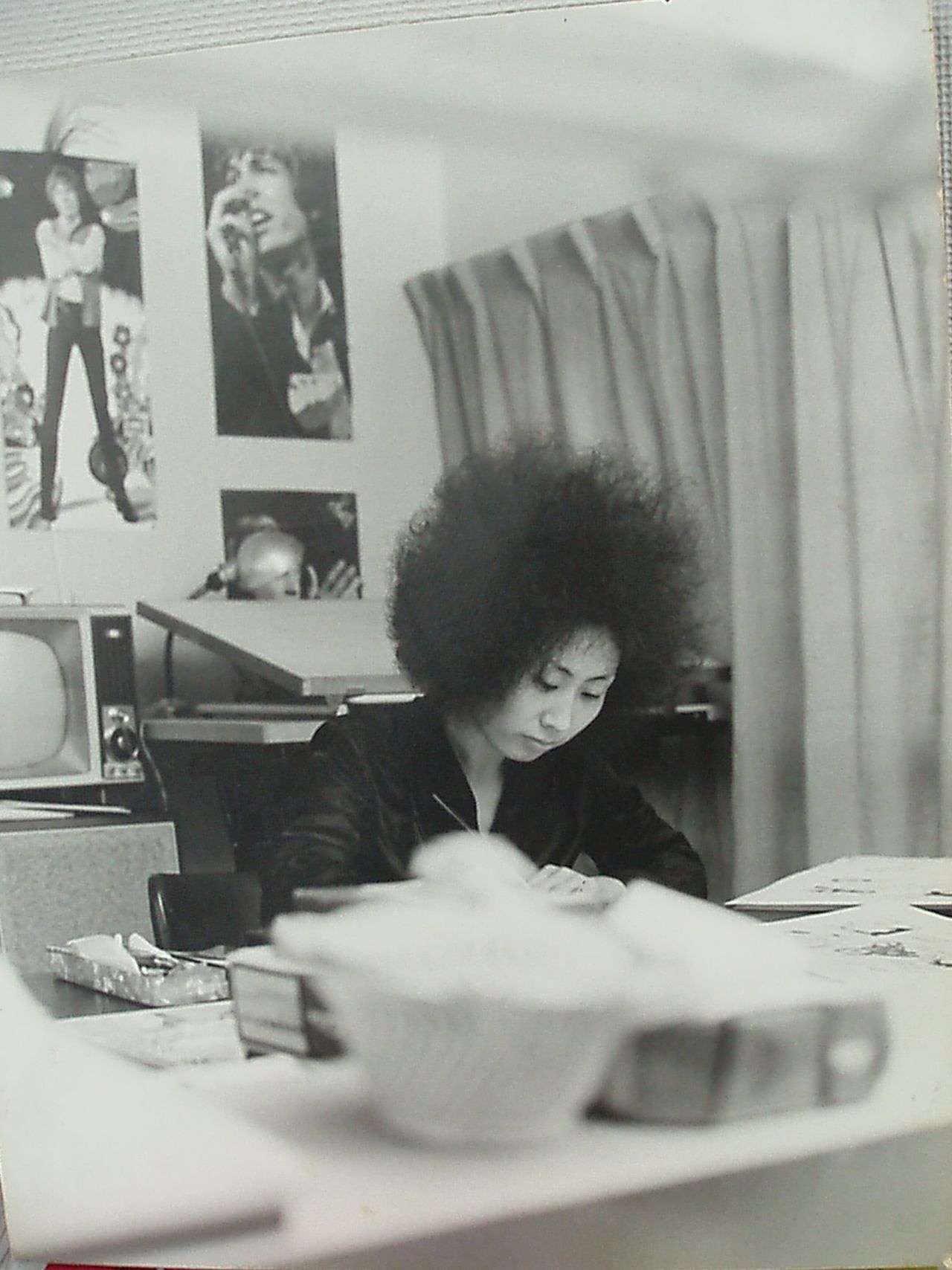

“I was fascinated at how this hidden side of the United States, the ‘land of the free,’ was being exposed, and thought it amazing that young people all over the world were rebelling against conventional society and material culture. I was drawn to the strong, complex, anti-establishment messages of rock music, especially prog-rock, and decided to depict rock in my work.”

The concept of the main character Aron, who is ruined by his simple love and pursuit of music, was based on Scott Walker, lead singer of the popular pop group the Walker Brothers. “I had this impression that, although his success had brought him great privilege, he still had doubts about his own sense of self. And then his solo on ‘Plastic Palace People’ really hit me. It’s a beautiful song, with wonderful abstract lyrics. Aron was born from that idea of utter purity.”

Mizuno at her desk, writing Faiyā! A poster of Scott Walker is on the wall behind her. (Courtesy of Mizuno Hideko)

She went on a research trip to Europe and the United States before her series started running. “The trip didn’t even last a month, but I went around and visited all of these centers for underground culture and clubs full of young people. Rock was playing in every city I went to, and I felt like all the world was connected.”

The work depicts the diversity of American society, with white, Black, and Native American characters. There are also nudity and sex scenes. “I drew the art to express the hippie message, which was to throw away all pretense and be your true self. There was no shortage of manga packed with sex scenes that came after my work, but these titles all came across more like pornography.”

Faiyā! got a huge response, and Mizuno saw a sudden spike in male readers. “For a while, most of my fan letters were from boys. It took a while for the work to break out among women readers.”

Regrets for an Unfinished Masterpiece

As the manga industry grew to be dominated by weekly magazines, artists began to be “closed off.” In search of exclusive access, companies sought to prevent editors with rival publications from contacting their favorite creators, but there was no talk of contracts. At first, as well, no one gave any thought to the potential for secondary use of the works, so many manuscripts were lost because of sloppy handling by publishers.

“I absolutely refused to be exclusive, and kept getting into fights with editors,” recalls Mizuno. “I’m sure they must have seen me as particularly rebellious or cocky.” While she was writing Faiyā! Mizuno learned about the concept of copyright and even held study groups with colleagues to get them up to speed on their rights. Publishers, though, nervous that she might try to start a union, got in the way of any progress. She was also told to end the story earlier than expected, and she had to tie the storyline off and wrap it up. “I think that was because of my other activities,” she says.

Her son was born two years after Faiyā! ended, and she became a working single mother. “I never imagined how hard it would be to raise a child alone. I gave up on long-form serials and filled in the gaps with illustration and other work. My income fell to about a quarter of what it was at my peak, but we made it through somehow.”

As a new generation emerged in the manga world, she got fewer requests from magazines for serial work. The one missed chance she still regrets is a serial based on the life of the Bavarian king Ludwig II. This was her first serial attempt after a long hiatus, and she even traveled to Germany to research it. It was broken off when the commissioning magazine went out of business. “Ludwig II was a devoted patron of Wagner, my favorite composer. I depicted his story as a tragedy of an overly pure youth, but I only got to do half of it. I took it to all kinds of other publishers, but no one wanted to revive it.”

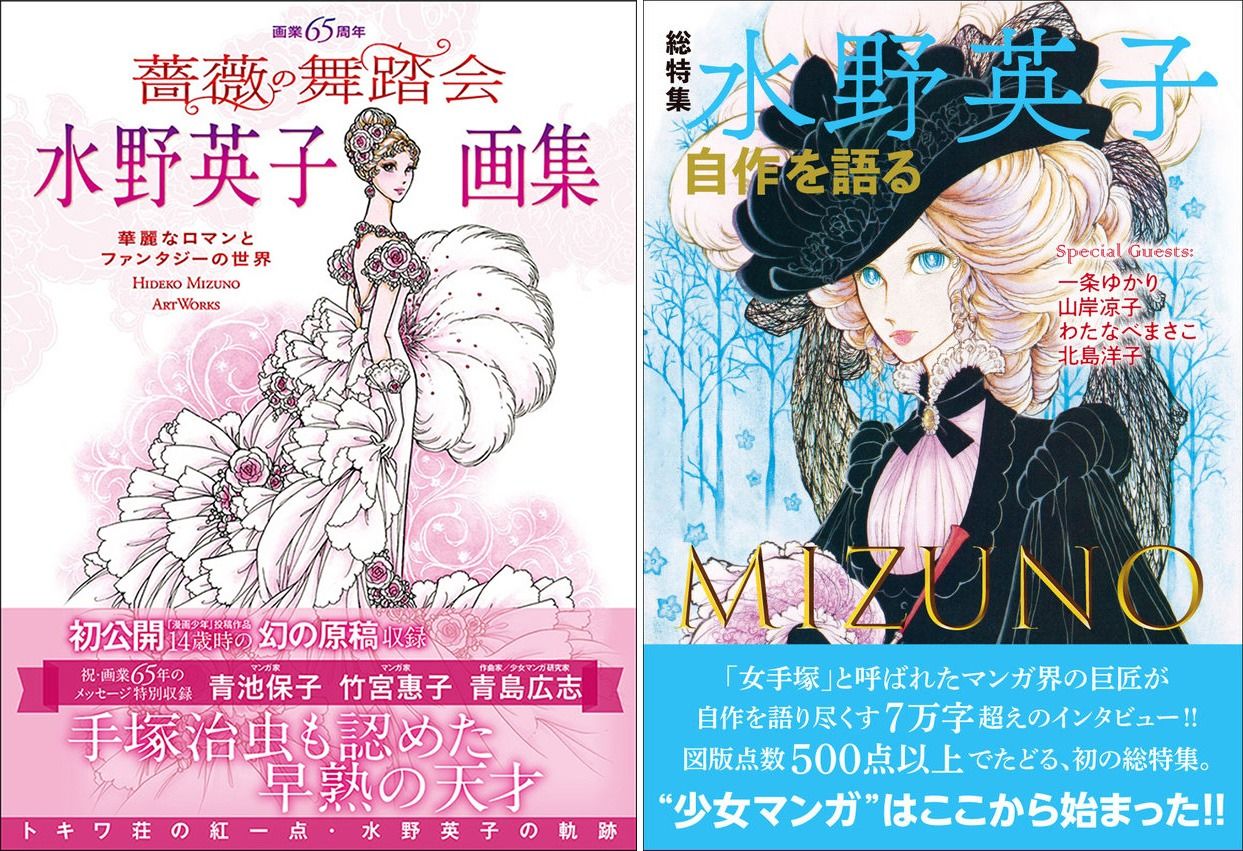

She says that now she doesn’t have the stamina to finish the work, but she still hopes to see it go on. “There are no records of our generation, those of us who took up the reins after Tezuka, so there appears to be a twenty-year gap between Tezuka’s Princess Knight and Ikeda Riyoko’s Berusaiyu no bara [The Rose of Versailles]. Of course, I want everyone to know how shōjo manga was in our days. In fact, I’ve got the help of a dozen or so artists active at the time to put together a record of what we did. I want to somehow get it all into a book and have everyone read about it.”

Several books looking back over Mizuno’s work have appeared, including the 2020 Bara no butōkai: Mizuno Hideko gashū (The Ball of Roses: A Mizuno Hideko Art Collection), at left, and the January 2022 Mizuno Hideko: Jisaku o kataru (Mizuno Hideko on Her Work).

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Hideko Mizuno’s most famous work, Faiyā! © Mizuno Hideko.)