Exploring Sumō: Unusual Techniques and the Sport’s Rising Stars

Sports Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

See the first part of this article: “Exploring the Match-Winning Techniques of Sumō”

Popular Moves in Early Sumō

Backward body drops, or soriwaza techniques that involve arching the upper torso backward, come in an amazing range of moves.

In the Edo period (1603–1868), there was no dohyō ring as such, and winning sumō techniques, or kimarite, like yorikiri (frontal force-out) or oshidashi (frontal push-out) which are common today, did not exist. In contrast, backward body drops were often used, and 12 such moves numbered among the traditional 48 kimarite.

A Muromachi period (1336–1573) illustration depicting what is most likely a sumō match. The circle formed by the spectators around the men may mark the origin of the dohyō. (Courtesy Ōzumō Journal)

The rule calling for sumō bouts to take place within a ring was established in the mid-seventeenth century, and for some time, any rikishi wrestler executing a backward body drop was deemed the winner even if his hand or bottom had touched the clay first. Since this move is quite showy, it was often used to add excitement and appeal to spectators.

But backward body drops had all but disappeared in tournaments by the mid-twentieth century, as they were considered too risky to execute. Ever since the Japan Sumō Association finalized its standard list of kimarite in 1955, the shumokuzori bell hammer backward body drop, the tasukizori reverse backward body drop, the soto-tasukizori outer reverse backward body drop, and the kakezori hooking backward body drop have never been used in the makuuchi division. Here is a rundown of the main backward body drop kimarite.

Former College Wrestlers Favor Izori

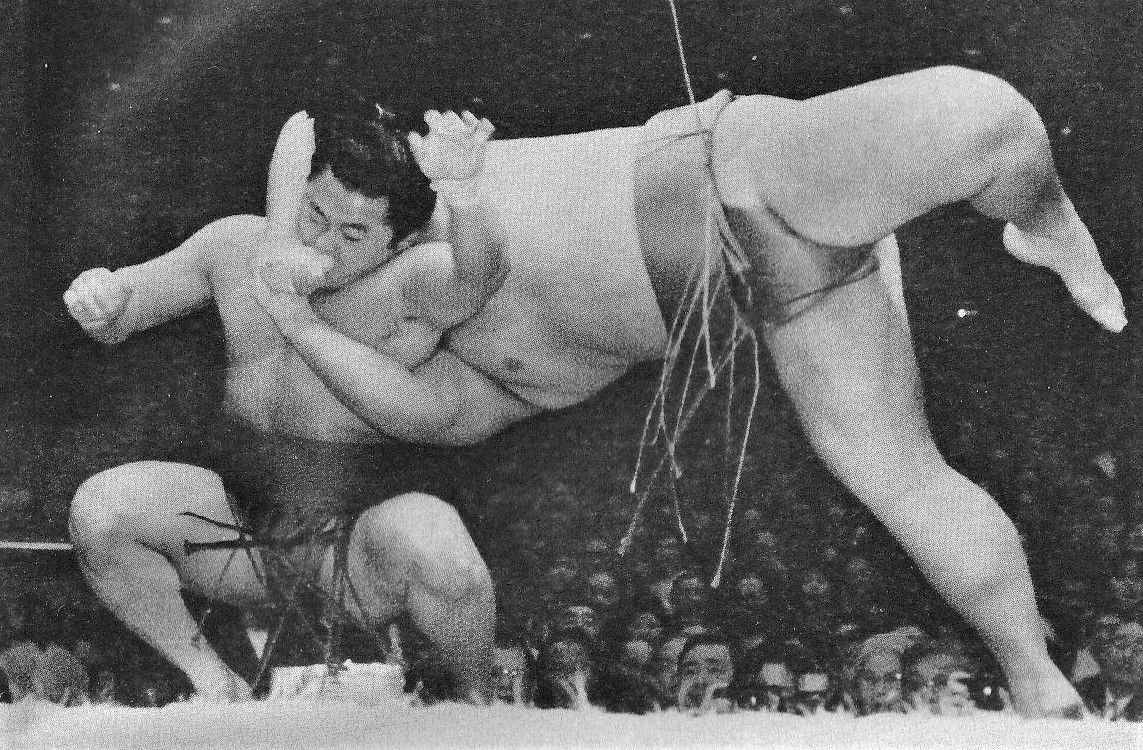

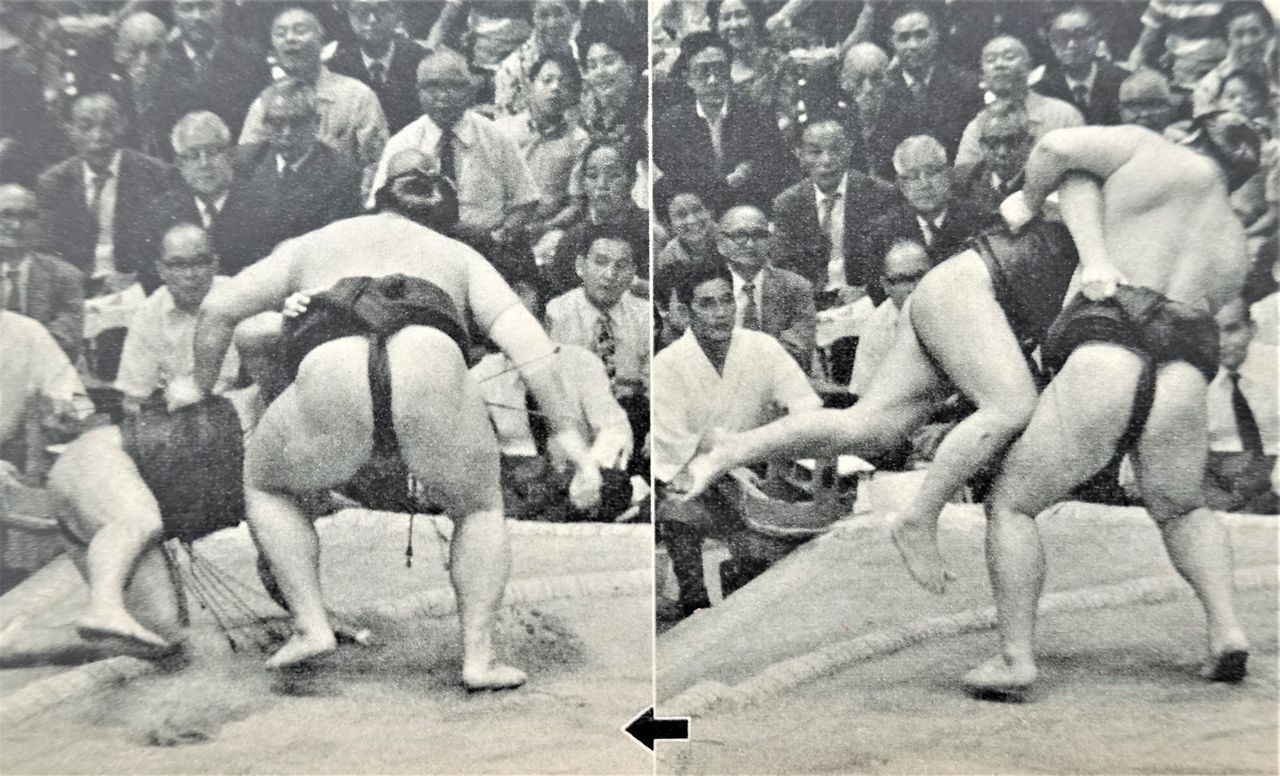

The izori backward body drop involves the rikishi on the offensive grabbing hold of his opponent’s extended arm, burrowing his head under the man’s other arm, and grasping his mawashi, bending backward to heave him to the clay. Izori has only been the kimarite twice at the makuuchi level since 1955: when Maenoyama downed Tatekabuto on the fourteenth day of the March 1957 basho, and on the second day of the May 1964 basho, when Iwakaze defeated Wakatenryū. Nearly 60 years after the last izori was performed, Mainoumi came close to pulling it off, on the sixth day of the January 1992 basho, against Takatōriki.

In his first fight against Mainoumi, known for a broad repertoire of surprise moves, Takatōriki took the unusual step of backing almost right up to the tokutawara recessed bales on all four sides on the edge of the dohyō for the face-off. After slaps and pushes between the two, Takatōriki got hold of Mainoumi’s neck when the latter circled behind him, and pushed him to the edge of the ring. Counterattacking, Mainoumi bent his upper torso backward to counterattack, but Takatōriki, leaning his own body against him, prevailed and won the match. Had Takatōriki dropped backward, the kimarite would have been the first izori in 28 years.

In the lower jūryō division, meanwhile, Tomonohana won against Hananokuni with izori at the January 1993 basho, as did Ura when he notched a victory against Kyokushūhō at the November 2020 basho.

The match between Mainoumi and Takatōriki at the January 1992 basho. Pushed to the edge of the ring, Mainoumi (left) attempts to pull off izori. (Courtesy Ōzumō Journal)

Mainoumi, Tomonohana, and Ura all hail from university sumō clubs. In amateur sumō, where some competitors are lighter or shorter, izori is used from time to time.

But unlike in amateur sumō and in the makushita and lower divisions, backward body drops are difficult for the physically much larger rikishi in the makuuchi class to execute. It would certainly be thrilling to see a makuuchi division rikishi pull off the spectacular izori, a kimarite that has not been seen at that level for a very long time.

Tasukizori (outer reverse backward body drop)

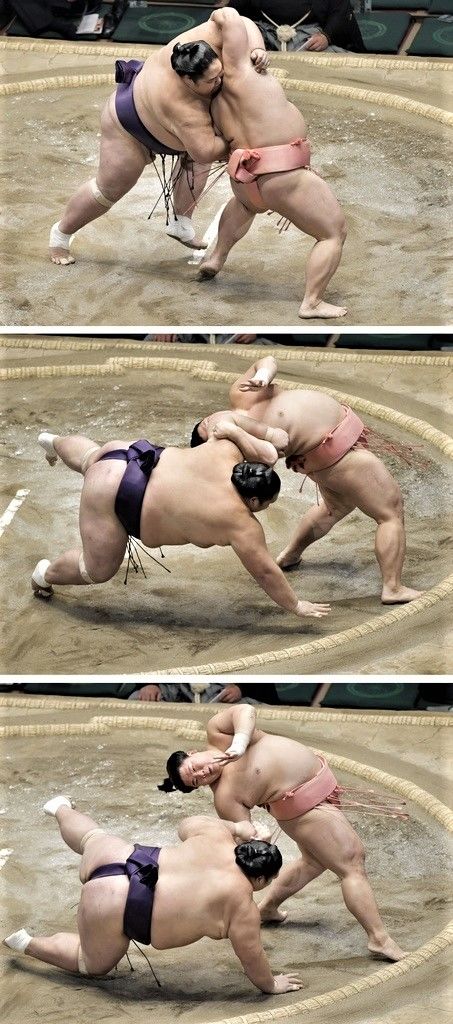

In this technique, the reverse backward body drop, the rikishi on the offensive lodges his head under the other man’s arm while dodging his grasp, uses his other hand to flip his opponent’s leg up from the inside, and bends back to down him. Although jūryō division rikishi Ura toppled Amakaze using this technique on the thirteenth day of the 2017 January basho, it has never been used so far at the makuuchi level.

Tasukizori is rarely used, but it was seen at the makuuchi level prior to its addition to the official list of kimarite in 1955, namely at the May 1951 basho, when komusubi (and later yokozuna) Tochinishiki won against 214-centimeter-tall Fudōiwa. When properly executed, this technique resembles a sash (tasuki) running diagonally across the body, from which the move derives its name.

The match between Ura and Amakaze at the January 2017 basho. (© Kyōdō)

Tsutaezori (under arm forward body drop)

In 2001, the JSA added 12 kimarite to its list of official techniques. One of these is tsutaezori, the underarm forward body drop, where the rikishi on the offensive burrows under his opponent’s arm, pulling on it and twisting him onto his back. In the makuuchi division, this technique has only been used once, when ōzeki (later yokozuna) Asashōryū downed komusubi Takanonami (highest rank: ōzeki) on the third day of the September 2002 basho.

In that match, Takanonami had gotten a grip on Asashōryū’s mawashi when Asashōryū pulled on Takanonami’s arm and got under his left side. Bending backward, he leaned on Takanonami, whose left hand touched the clay a fraction of a second before Asashōryū’s.

Asashōryū meets Takanonami at the September 2002 basho. The kimarite, initially announced as hikiotoshi (hand pull-down), was soon corrected to tsutaezori. (Courtesy Ōzumō Journal)

Ipponzeoi (one-armed shoulder throw)

In addition to the two backward body drops just described, other unusual or surprising techniques include ipponzeoi, the one-armed shoulder throw.

In this technique, the rikishi presses up against his opponent’s chest, uses both hands to grasp the man’s arm, hoists him onto his shoulder, and throws him forward. This is a familiar move in jūdō, and the jūdōka throwing his opponent can lower a knee onto the mat. Not so in sumō, where a knee on the dohyō means losing the match. The rikishi on the offensive is often crushed as a result of this move, so it is only rarely used in tournaments.

Ipponzeoi was seen for the first time after being included in the official list of kimarite on the twelfth day of the November 1974 basho, when Kaneshiro went up against Tamanofuji. Pushed to the edge of the ring by Tamanofuji, Kaneshiro grabbed Tamanofuji’s right arm with both hands and tossed him cleanly forward. It was a win for Kaneshiro but also offered the unusual sight of the rikishi, propelled by momentum, ending up in a headstand for a few seconds.

Smaller rikishi can use ipponzeoi effectively against tall opponents by leveraging the momentum they generate. The accepted wisdom was that two heavy rikishi would rarely if ever try to use ipponzeoi, but this was contradicted when Kaiō, weighing 172 kilograms and with a grip strength of over 100 kilograms, did just that.

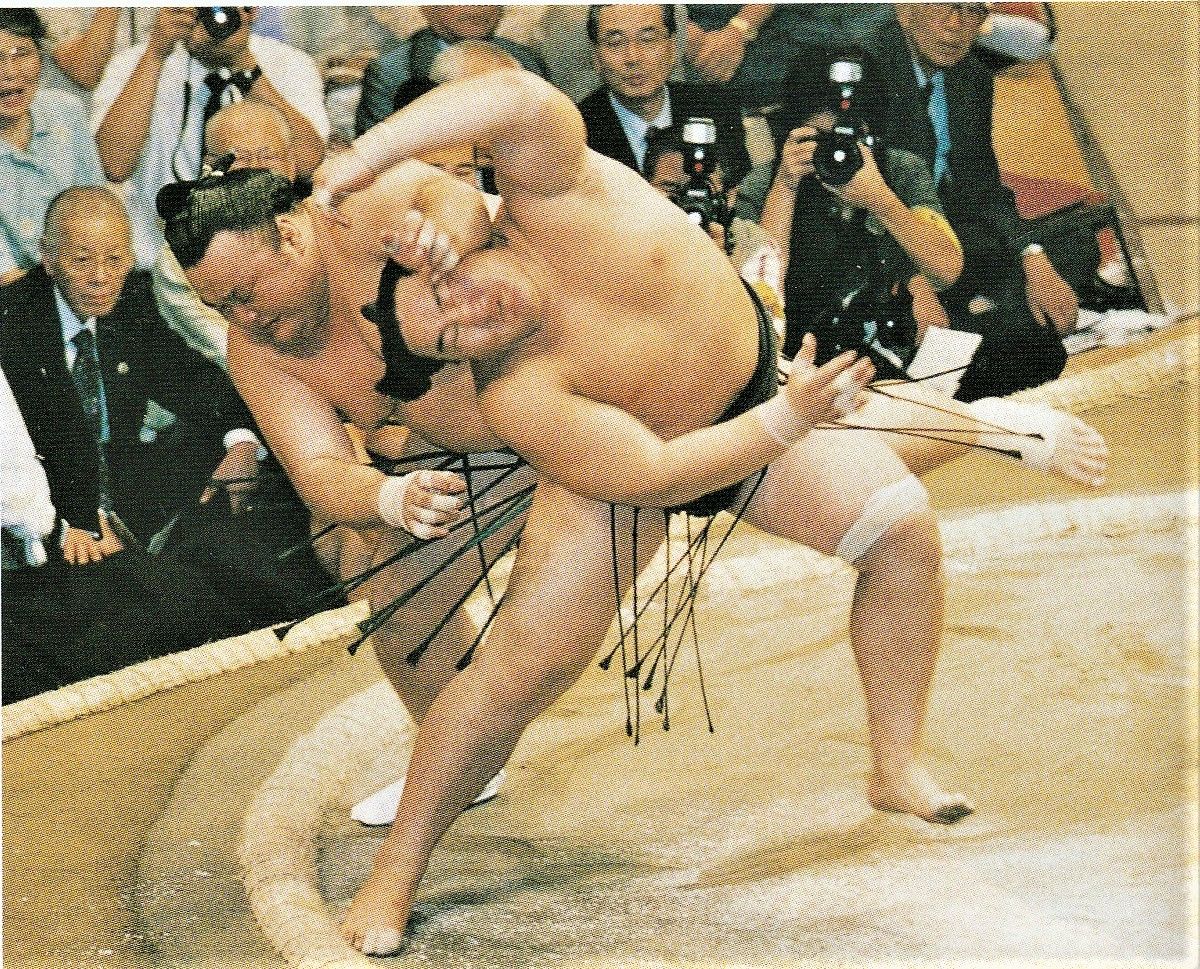

On the fourteenth day of the November 2000 basho, ōzeki Kaiō was paired against yokozuna Musashimaru. After using his left arm to loosen Musashimaru’s grip on his mawashi, Kaiō used both arms to grip Musashimaru’s right arm and went into ipponzeoi mode. Although Kaiō did not actually heave Musashimaru up, he was leaning on him from behind and Musashimaru, unable to keep his balance, touched out of the ring with his left hand. Kaiō, who had also practiced jūdō, used the borrowed technique to his advantage on this occasion.

Kaiō (right) forces Musashimaru out with ipponzeoi at the November 2000 basho. (© Jiji)

Matches have been won with ipponzeoi five times since then, most recently on the ninth day of the September 2021 basho when Hōshōryū downed Wakatakakage.

Hōshōryū had been forced to the edge of the ring by Wakatakakage, who had grasped Hōshōryū’s outside arm. Hōshōryū counterattacked, locking Wakatakakage’s right arm in both of his, and threw him over his shoulder. The referee initially declared Wakatakakage the winner, but the judges overruled him and awarded the match to Hōshōryū.

Hōshōryū and Wakatakakage on the ninth day of the September 2021 basho. (© Kyōdō)

Harimanage (backward belt throw)

In the harimanage backward belt throw, when a rikishi has both hands on the opponent’s mawashi, he reaches over his opponent’s head or shoulder to grasp his outer arm and throws him using a backward pivot. This technique has been used 29 times since its inclusion in the official kimarite list. Harimanage is usually performed using both hands but is recognized as such by the JSA even if only one hand is used. The name of this technique comes from how it is reminiscent of a wave smashing into rocks.

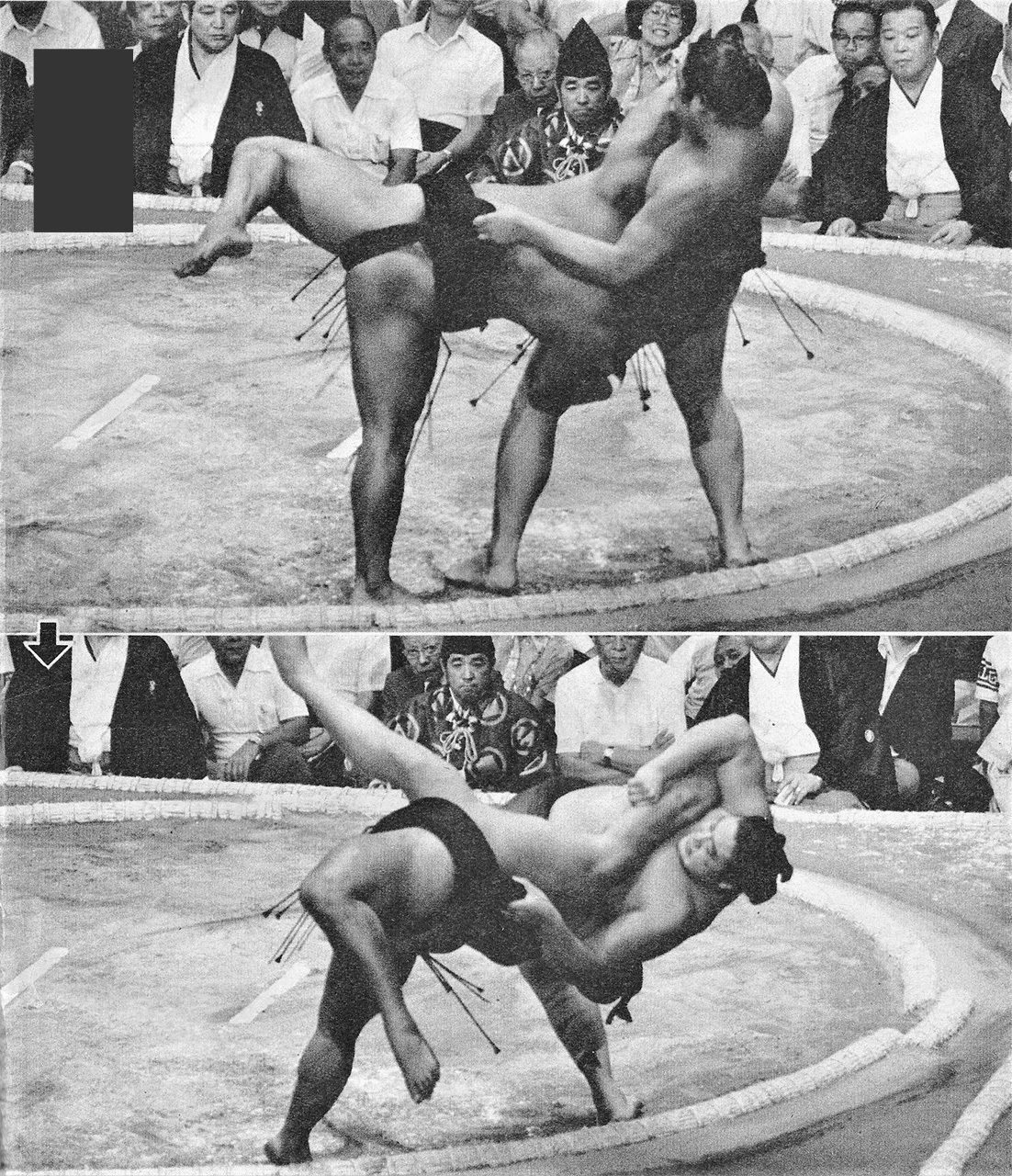

One rare instance of a stunning harimanage was the bout between ōzeki Wakamisugi (later yokozuna Wakanohana II) and sekiwake Washūyama on the first day of the September 1977 basho.

Washūyama, holding Wakamisugi’s mawashi in a two-handed underhand grip, forced him to the edge of the ring all at once, leaving Wakamisugi trying his utmost to stay in. Everyone was sure that Washūyama would prevail, but Wakamisugi, displaying unbelievable endurance, pinned Washūyama’s arm, reached over his shoulder to grasp his mawashi, and executed a one-handed harimanage.

Wakamisugi was known for extreme flexibility, and that match showed him at his best.

Many tall, barrel-chested rikishi employ harimanage, such as Estonia-born Baruto, who used the technique at the May 2006 basho against Iwakiyama, at the November 2010 basho against Aran, and at the July 2012 basho against Wakakōyū. The most recent use of harimanage was at the July 2021 basho, when Ichiyamamoto, newly promoted to the makuuchi division, used the technique against Ishiura.

At the September 1977 basho, Takamisugi, displaying astonishing lower body strength, pulls off an upset victory against Washūyama. (Courtesy Ōzumō)

Tsukaminage (lifting throw)

Four techniques have never been used despite being on the list of official kimarite decided by the JSA in 1955. Another, tsukaminage, or the lifting throw, has been used only once, on the sixth day of the November 1957 basho in the bout between sekiwake Tokitsuyama and komusubi Araiwa.

Tsukaminage is performed by grasping the opponent’s mawashi from the top with the outer arm and then hoisting his body before throwing him down. Whereas various throwdowns are done from right to left or vice versa, in tsukaminage the throw is right to right or left to left, exactly as if throwing a piece of rubbish to the ground. It cannot be used successfully unless there is a marked difference in strength between the two rikishi.

During practice bouts, a yokozuna or an ōzeki may sometimes demonstrate tsukaminage when grappling with makushita or lower division wrestlers. In tournaments, the technique was used five times during the 1940s and 1950s, so in earlier days it was employed from time to time.

The single example in more recent decades took place in the bout between ōzeki Daikirin and Masuiyama (who would later rise to ōzeki himself) on the twelfth day of the September 1972 basho. Daikirin, with a firm right-handed hold on Masuiyama’s mawashi, lifted him with his left hand, and threw him down using tsukaminage. It was a spectacular throw, but according to the JSA, Daikirin had won with a tsuridashi front lift-out.

Over the past 70 years, rikishi in the makuuchi ranks have gotten 40 kilograms heavier on average, and tsukaminage has become much rarer. Spectators would certainly enjoy the sight of a rikishi effortlessly pushing his opponent down.

Daikirin against Masuiyama at the September 1972 basho. At first glance, it looked as though Daikirin had executed a tsukaminage, but the official ruling was tsuridashi. (Courtesy Ōzumō Journal)

Three Rising Stars

As today’s rikishi have gotten heavier, many of them use pushouts as their main technique. This results in less variety in the range of kimarite used, compared to earlier days when techniques involving getting a grip on the opponent’s mawashi were more common.

Even so, some young rikishi are known for trademark showy, crowd-pleasing kimarite. One of them is Ura, a Kwansei University graduate born in 1992 who stands 172 centimeters tall and weighs 147 kilograms. The Osaka Prefecture native, who belongs to the Kise stable, often used izori and tasukizori to win his matches. But the unnatural posture he assumed to perform these moves exacted a physical toll. After suffering a serious knee injury, Ura plummeted near the bottom of the unsalaried ranks. Nevertheless, he made a brilliant comeback and is now in the top makuuchi division.

Abi, from the Miyagino stable, is another up-and-coming rikishi. Born in 1994 in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture and a graduate of Kanazawa Gakuin University, he is 168 centimeters tall and the only top division wrestler weighing less than 100 kilograms. The highest rank he has attained so far is fourth maegashira. Abi is similar in build to retired komusubi Mainoumi, who stirred up spectators in the 1990s with his array of surprise moves. Abi’s left-handed shitatenage underarm throws resemble Mainoumi’s, too. But he needs to work on developing more core body strength that would help him withstand being pushed out. The day may come when he too can use cunning techniques to topple behemoths.

A third promising young rikishi is Hōshōryū, from Mongolia, who is also the nephew of retired yokozuna Asashōryū. Born in 1999, he is 187 centimeters tall, weighs 132 kilograms, and belongs to the Tatsunami stable. His rank now is first maegashira. In his match against Wakatakakage at the September 2021 basho, he was driven to the edge of the ring but recovered by mounting a relentless pounding attack and downing Wakatakakage with an ipponzeoi after hooking a leg behind Wakatakakage’s knee. In that match, Hōshōryū displayed the phenomenal lower body strength he shares with his Mongolian compatriots. Sumō fans hope they will see more of thrilling action from him in the coming years.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The izori backward body drop is a difficult technique where the rikishi on the offensive drops down low to grasp his opponent’s knees and, arching his back, heaves him backward onto the clay. © Kyōdō.)