Tom Hovasse on Doing the Impossible and Olympic Basketball Victory

Sports Society Culture Global Exchange Tokyo 2020- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Always Aim for Gold

“For some reason Japanese athletes lose confidence when they play internationally. My work as head coach started with trying to figure out why this was.”

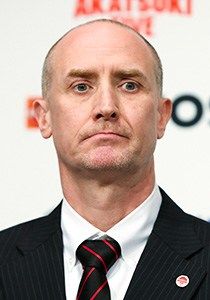

These are the words of Tom Hovasse, the man who led the Japanese women’s basketball team to win silver at the Tokyo Olympics. Born in the United States, Hovasse played professional basketball in the Japanese league for over 10 years. He also served as assistant coach to the Japanese national team at the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, where the Japan team made it as far as the quarterfinals.

“I told the players to aim higher, but they weren’t mentally prepared. They didn’t believe they could win a medal,” he reflects.

The first thing that Hovasse did upon being appointed to the position of head coach in 2017 was to assign his team a clear goal: Win gold at the Tokyo games. Tom says he believes the players were taken aback by this challenge, although they didn’t say so out loud. He recalls:

“The players were skeptical about their prospects, but I tried to inspire them by encouraging them to become the kind of team that fearlessly puts up three-point attempts, like the teams in the NBA, so that they could take on taller overseas players. I reminded them they were good from outside the arc.”

Having shared his strategy for winning at the Tokyo Olympics, Hovasse set about taking the steps necessary to achieve this goal. While the team finished ninth in the FIBA 2018 Women’s Basketball World Cup, it went on to win the 2019 Asia Cup. The postponement of the Tokyo Olympics due to the COVID-19 pandemic may actually have been worked in the team’s favor, giving it more time to hone its strategy.

That said, it was not until after the Tokyo games actually kicked off that the Japanese team became genuinely confident about its chances. In the first game of the group phase, Japan beat France, a team that finished fifth in the 2018 World Cup, by four points, allowing it to proceed to the quarterfinals, where it beat Belgium by one point in a last-minute comeback, before going onto play France again in the semifinal round, winning 87–71. While the team lost the final to team USA, it took home Japan’s first ever basketball silver medal, changing the history of the game in Japan.

Hovasse led the Japanese women’s basketball team to win silver at the Tokyo games on August 8, 2021, at Saitama Super Arena. (© Kyodo)

Hovasse says he was inspired by something one of his players said to him after the Olympics: “You believed me more than I believed in myself. Thank you, Tom.”

The athletes’ confidence in themselves was the product of their coach’s belief in them.

A Japanese Lack of Confidence

Whether you look at basketball or any other sport played in Japan, you get the impression that many elite athletes, despite playing at a national level, lack confidence. In a past interview, Hovasse surmised that in basketball, the issue stems from a lack of self-respect among players at the junior level.

“The team can afford to be more confident,” he said. “You won’t find a group of players this dedicated anywhere in the world. We’re talking about a group of ‘gym rats’ who practice shooting all day, every day, and spend their every waking moment in the gym. This regimen is ingrained in them from high school.”

He continued: “I didn’t like that. Instead of simply putting in long hours on the court, I’d rather see players think for themselves and use their time as they see fit. That way, they’re more likely to grow as individuals and play with depth. I sometimes chased players out of the gym, but I’m pretty sure they sneaked back when I wasn’t watching. They had me beat,” he laughs.

“Of course, that kind of work ethic is something to be proud of, but with this team, I didn’t sense the confidence and self-respect that normally comes with a work ethic like that. My first job was to change that.”

Putting in long hours is not the goal, says Hovasse. During practice, he got the players into the habit of asking themselves what they needed to achieve in training sessions, even short ones, to succeed in their games, and made them embrace meritocracy.

Hovasse’s work with the women’s team began with changing the players’ attitudes. (Saitama Super Arena, 2021; © AFP/Jiji)

Stigma Surrounds “Dirty Play”

Hovasse says Japanese players get into the habit of putting in long hours in high school. Even today, the leaders of many high school teams subject their players to long hours of practice and judge them based on how much time they spend on the court. There may be similarities between the way the leaders of such teams demand loyalty and clearly define the relationship of control between themselves and their teams and the workplace culture of old-fashioned Japanese corporations.

There is also a strong tendency for school basketball teams, an extension of the school’s extracurricular activities, to overemphasize adherence to the rules. However, this approach appears to be depriving the players of the ability to think for themselves. In basketball, a team trailing its opponent by a couple points late in the game may commit an intentional foul, sending the opponent to the free-throw line. While doing this creates a chance that the other team will sink both free throws, a miss on the second shot could give your team possession on the rebound, giving you a chance to even the score, or even to regain a lead with a three-point shot.

In the United States, such intentional fouls are very common and referred to as a “good fouls,” to the point that incorrectly executed intentional fouls attract criticism in the media. In Japan, however, coaches frown on intentional fouls, even at the national level. These coaches appear to have a preconceived notion that it is wrong to commit fouls. I myself have heard coaches tell their players not to “play dirty.”

Japanese club basketball demands such adherence to the rules, and there is pressure on players to play accordingly in order to be judged highly. This results in players thinking for themselves less and losing confidence in their play, which in turn creates a lack of self-respect.

If Japanese women’s basketball is going to compete at an international level in the future, it will need a culture in place for players from a junior level that encourages them to think for themselves, not just during games but during practice as well. Indeed, in basketball powerhouse Spain, whose national team won silver at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro games, you will find junior matches where there is no scoring whatsoever. In Spain, it is held that players in their teens should be learning how to think for themselves, hone their skills, and love the game, rather than focus on winning and losing.

Hovasse on the Japanese Men’s Future

By assigning his team the goal of winning gold at the Tokyo games, Hovasse proved that by doing away with the preconceived notions prevalent in Japanese basketball and changing its players’ attitudes, Japan could take on the world. Now, having made Japanese women’s basketball history, Hovasse has taken on another challenge. After the Tokyo games, he bowed out as head coach of the women’s national team to take a position as coach of the men’s team to prepare it for the 2023 World Cup.

Hovasse describes his new role as follows:

“I’ve heard people say ‘he’s never coached a men’s team.’ That’s irrelevant, however. Whether you’re coaching men or women, basketball starts with a process of building trust between the coach and the players. Fundamentally, the rules are the same. However, I’d be pushing things to set the Japanese men’s basketball team—ranked thirty-seventh in the world as of the end of 2021—a goal of winning gold, as I did with the women’s team. It’s unrealistic.”

Hovasse began training with the men’s team in November. Things did not get off to a good start, with the team tasting suffering two consecutive defeats against China in the Asian qualifiers for the 2023 Basketball World Cup. However, Hovasse was already stressing the importance of trust between coach and players.

“The team performed really well during training, but didn’t deliver in the games. Now we have to establish why that was. To do that, we need to hold plenty of training camps so I can build trust with the players.”

Hovasse’s first foray into coaching men’s basketball saw his team suffer two consecutive losses to China. Hovasse’s expression was often stern during the games. (Taken on November 28, 2021, at Xebio Arena Sendai; © Jiji)

However, Hovasse says male players face different structural issues than their female counterparts. Unlike the women’s league, which has no foreign players and whose top point scorers are all Japanese, in the men’s B. League, all of the top point scorers were born overseas. Therefore, local players often play second fiddle. Indeed, a look at the B. League rankings as of February 10 shows that foreign-born players dominate the top positions, as of February 10, 2022, with only four Japanese-born players making it to the top 50: Andō Seiya of the Shimane Susanoo Magic in twenty-fifth place, with 15.7 points per game; the Shinshū Brave Warriors’ Okada Yūta in twenty-eighth, with 15.5; the Kawasaki Brave Thunders’ Fujii Yūma in fortieth, with 13.7; and Togashi Yūki of Chiba Jets Funabashi in forty-seventh, with 13.1. All four players share the fact that they play point guard, a position typically taken by shorter players. In other words, the B. League’s tall Japanese players are not performing the role they are supposed to. Hovasse says this is a major difference between the men’s and women’s teams.

“Fundamentally, the women’s national team employs the same style of play as the teams in the women’s league, which means it’s possible to put together a national team whose style aligns with the players’ usual style. However, if I were to attempt to put together a men’s team based around three-point shots, as I did with the women’s team, I would end up with a different style of play from that adopted by the B. League. I believe it’s going to take longer to ingrain a teambuilding philosophy than it did with the women’s team,” says Hovasse.

Hovasse is thus applying his insight to identify areas that need improvement. His first games after making the switch to coaching men’s basketball were the Asian qualifiers for the 2023 Basketball World Cup played at the Okinawa Arena against Taiwan and Australia on February 26 and 27, 2022; Japan eked out a 76–71 win against the Taiwanese side and lost 80–64 against regional powerhouse Australia.

The Japanese men’s basketball team has only just set off on a four-year journey. It remains to be seen what kind of “prescription” Hovasse will issue to shape the team’s future.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Tom Hovasse gives instructions to a player at the game against China in the first round of Asian qualifiers for the 2023 Basketball World Cup on November 28, 2021, Xebio Arena Sendai. © Jiji.)