Medical Access for All: A Taiwanese Doctor’s Work to Bring Care to All Parts of Japan’s Society

Health Society Global Exchange- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Dr. Jo Tatsunori, a pulmonary specialist by training, launched the Online Home Doctor service last year. His aim was to provide needed medical services to foreign residents of Japan and to inhabitants of the country’s far-flung regions underserved by medical care.

Jo says it was only natural for him to enter a medical career, as his father and grandfather before him were both physicians. After earning his MD from Kaohsiung Medical University in 2013, he went to work as a doctor in Taiwan. Having been born in Japan, though, where he lived up through age five, his ties with the country drew him back, and he moved to Japan to work in 2015.

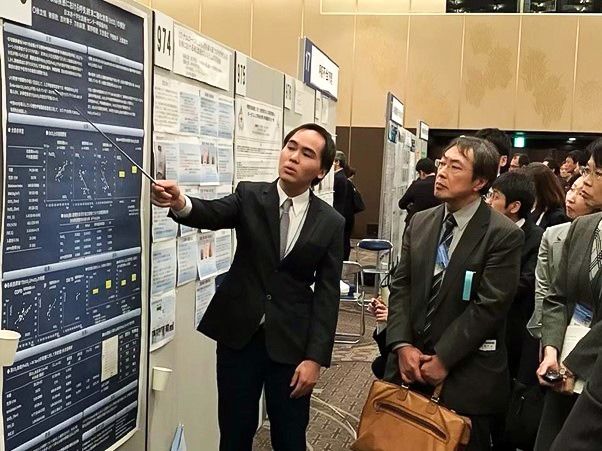

Jo gives a presentation on his research findings at a gathering of the Japanese Respiratory Society.

Taking On the Language Barrier

Taiwan produces many people of an entrepreneurial bent, or who head abroad, as part of their efforts to carve out their own success. Jo found himself in both of these categories when he came to Japan and launched a new medical service reaching out to society’s more disadvantaged members, such as foreign nationals and residents of remote regions who find it more difficult to access needed care.

In 1970 Japan’s population aged 65 and over numbered just 7.4 million. By 2020, this figure had ballooned to nearly 36.2 million, a leap of 500% in five decades. Seeking to offset dwindling numbers in the younger working generations, the government has been moving to boost immigration, such as by establishing new statuses of residence for foreign workers in 2019. Up until the COVID-19 pandemic effectively halted immigration, Japan had been adding some 200,000 new foreign workers to its population annually.

As of the end of October 2021, the population of foreign workers in Japan stood at 1,727,221. By nationality, the largest group among these was Vietnamese, accounting for 26.2% of the whole—and around half of these Vietnamese laborers, some 200,000 people, were in Japan on technical trainee visas. Compared with workers engaged in higher-level employment, these laborers often have lower Japanese proficiency, presenting a language barrier that prevents them from effectively accessing medical-care resources in the country.

Jo notes that as a doctor, he has treated numerous patients whose lack of Japanese language ability has kept them from communicating with their care physicians in the past. His own ability to speak Japanese, English, and Chinese has allowed him to serve as a medical interpreter in addition to an examining physician for many foreign patients. While the recipients of Jo’s care are fortunate to have encountered him, though, there are many more foreigners in the country who have given up on needed medical treatment due to the communication barrier—in some cases leading to severe illness and even death. This was a factor driving Jo in his decision to launch his new project, he says.

Jo demonstrates cutting-edge bronchoscopy technology for a group of visiting doctors from overseas.

The Challenges of Medicine in Far-Flung Regions

In 2017 Jo was working at the Japanese Red Cross Medical Center in Shibuya, Tokyo, as a senior resident in the respiratory internal medicine department. At this time he was sent to the JRC Urakawa Hospital in Urakawa, Hokkaidō, for a two-month stint what was his first exposure to the medical field in an underpopulated area.

The Urakawa facility, around three hours from Sapporo by car, is a key regional medical center, with 200 beds and an array of cutting-edge treatment and diagnostic equipment on hand. The surrounding region, however, is designated as a depopulated area with insufficient access to medical resources. The resources in question are not advanced medical machines, though, but rather the doctors, nurses, and other professionals whose expertise and experience cannot be replaced by such machinery.

The Japanese Red Cross Urakawa Hospital.

His experience at Urakawa was four years ago, but Jo remembers it clearly to this day: “There we were, in this huge general hospital, with only three physicians on duty! We had an ophthalmologist handling patients in the internal medicine department, and the doctor in charge of diabetes treatment would also be dealing with the lung cancer patients. It was all over the place.”

The doctor on duty on any given day, when confronted with a case requiring specialized attention, would have to put the patient in an ambulance headed for a hospital in Sapporo, three hours away. If the doctor felt there was a need to accompany the patient on this trip in case of a sudden change in his or her condition, it also meant calling up one of the other physicians not on duty that day. It was far from unusual for the doctors to give up their days off in this way, recalls Jo.

It was this experience at Urakawa that inspired him to tackle the problems of medical care in underpopulated areas.

Jo, at center, provided needed expertise in pulmonary medicine at the Urakawa hospital.

A Pandemic Provides a Push

The emergence of COVID-19 in late 2019, and its explosion into a global pandemic in the following year, produced tremendous upheaval in the medical profession. In some regions, shortages of healthcare workers and the outbreak of clusters of infections brought the medical system to the brink of collapse; in other places, people with chronic conditions and patients whose symptoms were not so serious stayed away from hospitals and clinics in droves, delivering a financial blow to many medical businesses. All of this reinforced Jo’s belief that the time for online medical consultations had arrived.

In 2021 he launched the Online Home Doctor website. Today this web-based operation has grown to employ 16 doctors, who can perform medical examinations and consult with patients online and even write prescriptions as needed. The web service is foreigner-friendly, with information available in Chinese and English as well as Japanese; OH Doctor can also serve patients speaking Vietnamese and Indonesian with the help of interpreters.

Jo has also worked closely with organizations overseeing the invitation of technical trainees to Japan, connecting these foreign residents with his online medical services. In doing so, he strives to ensure that these new arrivals secure their right to proper medical care while also helping the organizations hiring them to provide a healthier labor environment.

Upon receiving word from a technical trainee that he or she will miss work due to physical ailment, the hiring organization contacts OH Doctor to arrange an online consultation for the worker, or an examination and drug prescription as needed. In cases going beyond the ability of doctors to handle online, OH Doctor contacts hospitals equipped to provide care in the patient’s native language and provides an introduction to their services.

One key difference between OH Doctor and traditional clinics is the follow-up services. A week after an online consultation, staff from OH Doctor contact patients to check on their condition, providing additional help as required. Jo says the goal is to deal with these people not just professionally as customers, but with warm care.

“High-quality medical care means treating a patient like a friend,” says Jo. “If you do this, you create relationships of trust. At OH Doctor, we tell our patients to think of us as their friends, and to contact us at any time if they don’t feel so well.”

Generally speaking, patient-doctor relationships in Asia tend to involve the doctor providing a solution to the patient’s issue, and the patient following the doctor’s recommendations for treatment and medication. In many Western countries, however, this relationship is on a more equal footing, with patient and doctor working alongside one another in a collegial, or even friendly manner, and the patient receiving advice from the doctor and selecting from a menu of options provided by the specialist.

Online Treatment Moves Toward a Brighter Future

So how far can online medical care actually go as a replacement for in-person examinations? Jo is confident that we are far from the limits that can be reached: “In the future, it’s inevitable that technology and medicine will be even more closely fused. In other countries, we’re seeing progress in the development of self-use stethoscopes and even endoscopes for viewing the nasal and throat cavities, all of which can be used by patients as they confer with doctors online. Much of this work is still in the trial phase, but as it nears real-world usability, we’re going to see a change in the way people think about online medicine.”

In Asia, though, the online medical field is not as advanced as it is elsewhere around the world, and broad popular distrust in and outright rejection of online checkups remain the norm. Many people continue to feel that a doctor interfacing virtually cannot accurately grasp a patient’s actual condition, that the services provided are limited, and that there is a higher chance of misdiagnosis leading to errors in treatment.

Jo notes that these worries are misplaced, though. “Online treatment is never going to replace all medicine. We’ll make use of the online option for less serious symptoms and illnesses that aren’t so urgent and, based on the possible conditions, have the patient come in for more targeted advice and treatment as needed.” Even for patients in need of more urgent care, he notes, they do not always have easy physical access to a doctor. Online care gives these people a way to enjoy longer-term follow-up care from physicians in facilities with advanced treatment techniques, even when they live in remote, depopulated areas.

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed online medical care into an entirely new phase. In April 2020, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare implemented new rules allowing expanded use of online medical services, including for examinations of first-time patients. Restrictions on remote issuance of prescriptions have also been relaxed, making it possible for doctors to carry out online examinations and immediately send prescriptions to pharmacies so they can be filled and delivered to the patients at home. There are still limits to the sort of medications that can be prescribed in this way, but this has been a great step forward for online treatment in Japan.

A report published in June 2020 by the Mitsubishi Research Institute on personal health management and public views of treatment at medical institutions showed that some 60% of survey respondents viewed online treatment in a favorable light. There are naturally limits to what can be accomplished via online medical care, but technology is constantly evolving, and many companies are dedicating vast R&D budgets to pushing this area forward. As Japan enters a new era of medical services for its people, doctors like Jo Tatsunori are working to bring fresh ideas to the field.

(Originally published in Japanese. All photos courtesy of Jo Tatsunori.)