The Queen of Japanese Pop: Celebrating 50 Years of Matsutōya Yumi

Culture Music- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

New Music Shows the Way Forward

To grasp Matsutōya Yumi’s enduring presence on the Japanese music scene, one only needs to take a quick glance at the following statistics. In the five decades since her debut, no other artist has remained so consistently at the forefront in terms of both domestic sales and artistic achievement, and it is safe to describe her as a figure without equal.

- All-time artist sales: 40.04 million units; 8th place in all-time ranking

- Number 1 albums: 24 (19 standalone albums, 5 compilations); 2nd place (1st place solo/female artist, second in overall ranking only to rock band B’z [30 Number 1 albums])

- Consecutive Number 1 albums: 17 (from Sakuban Oaishimashō [1981] to Cowgirl Dreamin’ [1997]); 1st place

- Consecutive decades with Number 1 album: 5 (1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s); 1st place

- Top 10 albums (excluding compilations): 39 (every single album released under own name)

(Figures represent domestic Japanese sales/chart performance; Source: Oricon Inc.)

Born Arai Yumi in Hachiōji, Tokyo, in 1954, she made her songwriting debut in 1971 at the age of just 17, with a credit for Kahashi Katsumi’s “Ai wa totsuzen ni” (Love Comes Suddenly). Despite her own reservations, having only just enrolled at Tokyo’s Tama University of the Arts, her first named appearance as a solo artist came the following year with the self-penned single “Henji wa iranai” (No Need to Write Back), produced after prompting from Murai Kunihiko, a legendary composer in his own right and founder of the influential label Alpha Records.

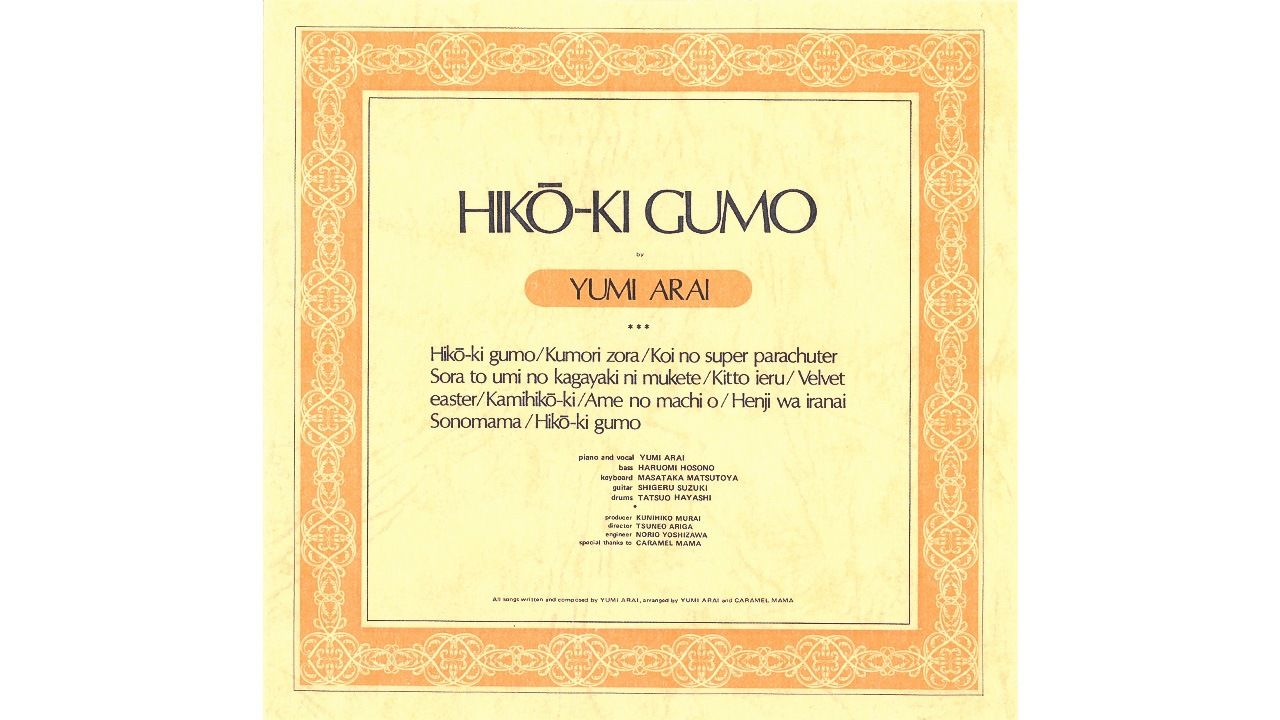

In 1973, a year when the pop charts were still dominated by enka ballad-tinged kayōkyoku (popular songs) like Chiaki Naomi’s “Kassai” (Applause) and folk songs like “Kandagawa” (Kanda River) by the group Kaguyahime, Arai Yumi released her debut album Hikōkigumo (Vapor Trails).

In stark contrast to the ponderous, brooding tone of the aforementioned hits of the day, the music of Yūming—as her fans came to affectionately call her—was sophisticated and evocative of modern city life, with a light, crisp quality influenced by her love of classical music (underpinned by piano lessons from the age of six) and Western artists such as Procul Harum and Françoise Hardy. A further contemporary edge was provided by the deft interplay of a backing band consisting of Hosono Haruomi (bass), Suzuki Shigeru (guitar), Hayashi Tatsuo (drums), and future husband Matsutōya Masataka (keys), collectively known at the time as Caramel Mama (later to evolve into the pioneering exotica unit Tin Pan Alley).

What set Yūming’s music apart was the combination of Western pop-style chord progressions and arrangements with beguiling lyrics shot through with a youthful sensibility, while a deft smattering of foreign words like “rouge,” “freeway,” “Milky Way,” “cobalt,” “station,” and “blizzard” only served to heighten the aura of stylish modernity. What’s more, the subject matter ditched established lyrical archetypes of the wronged or adoring woman for the cool new perspective of an independent young female. At the time, critics branded Arai’s oeuvre “new music,” but, in retrospect, she set the template for various future movements, including the urbane city pop that is currently finding new fans among a global audience, as well as the broader future of J-pop.

Marriage in November 1976 marked the transition from birth name Arai Yumi to the now familiar Matsutōya Yumi. (© Kyōdō)

From Hitmaker to Trendsetter

The most passionate audience for Yūming’s music was a young female demographic attuned to the latest trends. These loyal supporters made each album into a megahit and packed the concert halls on every tour, installing her as the undisputed queen of Japanese pop.

Her first number-one album arrived in 1976, with her fourth opus Jūyon-banme no tsuki (Fourteenth Moon). In a year of milestones, it would also be her last album under her birth name, as her marriage that November to backing band stalwart Matsutōya Masataka cemented a musical partnership that continues to the present day, with songwriting and lyrical duties for each track on every subsequent release handled by Yūming herself, and arrangement and production shouldered by Masataka. It is the same division of labor employed by another notable wife-and-husband duo, Takeuchi Mariya and Yamashita Tatsurō, and it seems clear that one key to both partnerships’ success is the presence of an arranger who is at once the songwriter’s closest companion and most trusted musical collaborator.

Indeed, according to Masataka himself, when it comes to arrangement, he enjoys such creative control that he has even been known to completely discard the chord progressions of songs provided by Yūming and rewrite them from scratch to arrive at what he sees as the most suitable setting. And while this revelation may at first come as somewhat of a shock, it also affirms the importance of Masataka’s production skills to his wife’s enduring success and record-breaking sales.

From the early 1980s onwards, Yūming’s assault on the pop charts gathered further momentum, and one particularly crucial release was 1980’s Surf & Snow, her tenth album and sixth as Matsutōya Yumi. While previous releases had featured songs inspired by summer, sun, surfing, skiing, and snow, as well as Christmas and other key events in the calendars of young lovers, 1987 saw the use of two songs from this particular record in the smash-hit movie Watashi o sukī ni tsuretette (Take Me Skiing): “Sāfu tengoku, sukī tengoku” (Surf Heaven, Ski Heaven) as the main theme song and “Koibito ga Santa Kurōsu” (My Sweetheart is Santa Claus) as a piece of incidental music, reinforcing Yūming’s voice as a near-ubiquitous presence that year.

Matsutōya Yumi and husband/collaborator Matsutōya Masataka accept the Cultural Merit Award at the 2017 Ski Association of Japan Snow Awards. (© Jiji)

Parallel to this, she began to establish performing relationships with popular resort destinations. From 1978, she appeared each summer at Kanagawa Prefecture’s beachside Hayama Marina, followed from 1981 onward by annual winter concerts at the Naeba Prince Hotel, a prominent ski destination in Niigata Prefecture. As well as a chance for resort-goers to gather and enjoy the seasonal outdoor spectacle, these events also served to promote emerging aspirational lifestyles.

Always one step ahead of the curve, Yūming had correctly sensed the coming economic bubble. With Japan entering the age of a “hundred-million middle class” society, no other musician so adroitly captured the changing mood of the times. Matsutōya made the transition from the personal musical novellas of her earlier work, becoming a leading trendsetter as she projected a new feminine ideal that was active and assertive in both love and leisure. The 1980s and 1990s saw her reborn as both a youth influencer and a romantic guru.

This same period also brought a 16-year unbroken streak of 17 consecutive number one albums, stretching from her twelfth song suite Sakuban oaishimashō (Meet Me Last Night, 1981) to her twenty-eighth, Cowgirl Dreamin’ (1997). Each new record became a nationwide event; I clearly remember the buzz around Tokyo on release days, and no singer-songwriter or artist before or since has gone on to so utterly transcend the boundaries of music.

Immortal Hits with a Life of Their Own

As Yūming herself predicted, “When my run of number ones comes to an end, it’ll be because Japanese society has changed.” And from 1997 to 1998, with banks and securities brokerages failing one after another, and the inexorable economic growth that had characterized the postwar years stuttering to an abrupt halt, her twenty-ninth album Suyua no nami (Waves of the Zuvuya, 1997) peaked at only number two in the charts. The following year saw the debut of Utada Hikaru, and as the music world shifted, Matsutōya, too, set off on a new path, including a partnership with the Great Moscow State Circus on Shangri-La, a new entertainment show that launched in 1999.

But in the 2010s, in times of need, Japan turned again to Yūming. In March 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami wreaked devastation on an unprecedented scale. And in the aftermath, Matsutōya’s 1994 song “Haru yo, koi” (Come, Spring) emerged as a unifying symbol of recovery. The following year saw the release of her first-ever career-spanning best-of collection Nihon no koi to, Yūmin to (Yūming and the Loves of Japan), which carried her once more to the top of the album charts, bringing her music to an entirely new generation.

Then, in 2013, she reached an audience that was global as well as multigenerational, when “Hikōkigumo,” the opening/title track of her debut as Arai Yumi, was selected as the theme song for Kazetachinu (The Wind Rises), the feature-length directorial return of anime legend Miyazaki Hayao after a five-year hiatus.

Matsutōya performing at an event to mark the opening of ski season, November 2019. (© Jiji)

And in 2020, with the world in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, her 1974 classic “Yasashisa ni tsutsumareta nara” (Embraced in Softness) took on a new and poignant meaning during NHK’s annual New Year’s Eve musical extravaganza Kōhaku uta gassen, when it was unexpectedly dropped into a medley by Yūming herself, accompanied by the comedy trio Small Three.

In recent years, Matsutōya has expressed a desire for her songs to live on beyond any recognition for their creator: “It’s fine for the author or the singer to be forgotten,” she says. “My only hope is that the songs will continue to be heard, and to be sung.”

Numerous Yūming compositions have entered the canon as much-loved standards, both her own songs and those written for others under the penname Kureta Karuho (a play on the name of actress Greta Garbo), including such hits as Matsuda Seiko’s 1982 “Akai suīto pī” (Red Sweet Pea) and Yakushimaru Hiroko’s 1984 “Woman ‘W no higeki’ yori” (Woman, from “W’s Tragedy”). Her songs have been treated to hundreds of cover versions, appearing on recent albums by the likes of Imai Miki and Juju, and even a growing number of compilations dedicated to Matsutōya interpretations.

And with multiple Yūming songs also found in school textbooks, you can be sure that at any given moment, someone, young or old, is singing one of them. It does not take a big leap of imagination to presume that several hundred years from now, somebody, somewhere in the world will still be listening—and singing along to—“Yasashisa ni tsutsumareta nara.”

(Banner photo: Hikōkigumo, Matsutōya’s 1973 debut album, released under her birth name, Arai Yumi. © Universal Music.)