The Black Ships Shock: A Historic Encounter that Changed Japan

Society Politics Culture World History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

From Fear to Curiosity

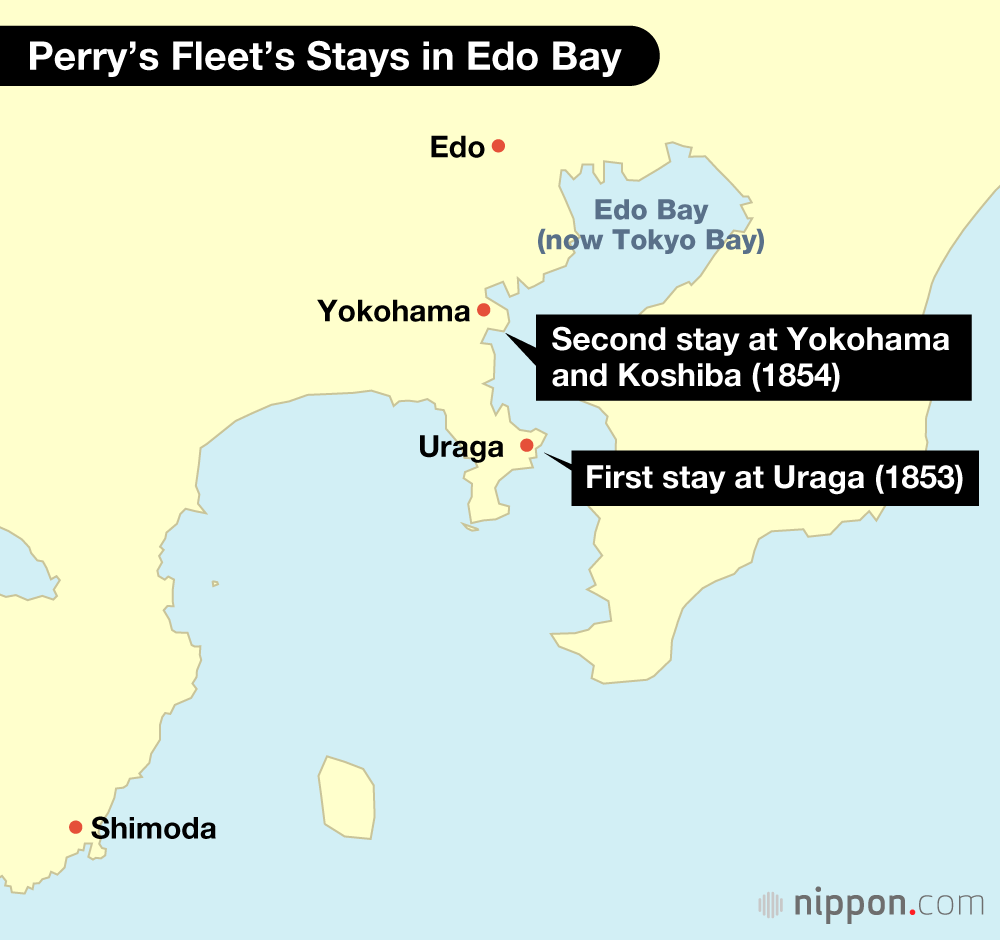

US Navy Commodore Matthew Perry first arrived off Japan with a fleet of ships at Uraga, the entrance to what is now Tokyo Bay, on July 8, 1853. On his second uninvited visit, the ships dropped anchors on February 13, 1854, near the villages of Yokohama and Koshiba (both locations are in the modern city of Yokohama). Negotiations between the two sides began in Yokohama on March 8, and the Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity was signed on March 31.

Perry’s fleet left Tokyo Bay on April 14, moving on to the newly opened port of Shimoda in modern-day Shizuoka Prefecture, meaning that the people of the area had a total of around two months to see the “black ships” up close. There were nine vessels with more than 2,000 crew members, who frequently came ashore and astonished the local residents with their Western goods.

| Year | Date | Movements of Commodore Perry and US Ships |

|---|---|---|

| 1852 | March 24 | Perry appointed commander of East India Squadron. |

| 1853 | July 8 | Perry’s fleet arrives in Uraga, by Tokyo Bay. |

| July 17 | Fleet moves to Naha. | |

| August 7 | Fleet moves to Hong Kong, and remains around Hong Kong and Macao. | |

| 1854 | January 23 | Fleet returns from Hong Kong to Naha. |

| February 13 | Fleet drops anchor in Tokyo Bay near Yokohama and Koshiba. | |

| February 27 | Shogunate decides to hold Japan-US negotiations in Yokohama. | |

| March 8 | First round of negotiations. Shogunate holds banquet with Japanese cuisine. | |

| March 21 | Test of model steam locomotive in Yokohama. | |

| March 27 | Perry holds banquet for shogunate officials on the flagship USS Powhatan. | |

| March 31 | Japan-US Treaty of Peace and Amity signed. | |

| April 14 | Fleet moves to Shimoda. | |

| June 2 | Fleet moves from Shimoda to Naha. | |

| July 17 | Fleet’s last vessel departs Naha for Hong Kong. |

When the fleet first anchored at Uraga, it triggered a boom in black ships sightseeing, drawing large crowds. Among the records of visitors, one observer who made a living in shipping wrote that it was “like looking at castles floating in the ocean,” and left detailed notes in a diary about the vessels’ paddle wheels and onboard cannons.

Initially, there was fear of the fleet. A priest’s February 1854 diary entry describes Perry’s chief of staff Commander H. A. Adams leading a party of soldiers ashore at Yokohama for the first time, and records that “Villagers fearing the outbreak of war if negotiations broke down moved their household goods away from the sea.”

However, concerns over conflict diminished with the progress of talks, giving way to a strong sense of curiosity as locals interacted with US crew members. The priest wrote in April that when the ships left, “villagers were even sorry to see the sailors go.” It was fortunate that the treaty was completed without the use of force. This sense of affinity seems to have encouraged a later openness to the adoption of aspects of Western culture in the leadup to the Meiji era (1868–1912).

Commodore Perry (right) and Commander Adams in Beikan torai kinenzu (Pictures Commemorating the Arrival of US Warships). (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

Presents for the Shogunate

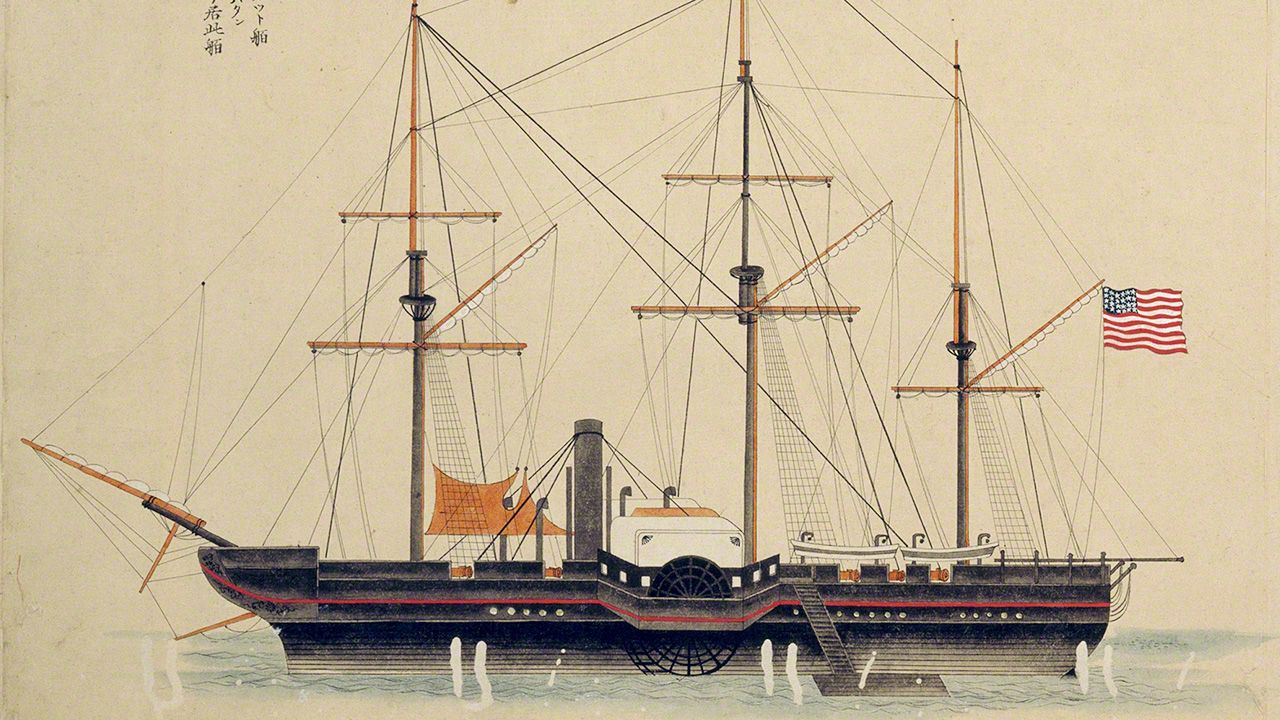

While the fleet was off Yokohama and Koshiba, visiting Edoites were amazed by the stately steamships equipped with their giant paddle wheels. The flagship USS Powhatan had a tonnage of 2,415, which was an order of magnitude greater than the 200 tons or so for large Japanese vessels. There were fishing grounds for the Edo population in Tokyo Bay, so many fishing boats went out there. Other vessels loaded with goods passed by on the way to the shogunate capital. Many of those on board had a chance to view the fleet from nearby. The giant ships were a terrifying sight, and their presence soon became well known in Edo and other communities around the bay.

People viewing the ships from the village of Koyasu (now part of Yokohama). From Kurofune raikō fūzoku emaki (Picture Scroll of Customs Around the Arrival of the Black Ships). (Courtesy Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore)

In the first round of treaty negotiations, the shogunate hosted a banquet. A Japanese official who was present wrote of the US sailors cutting their food with small knives and using what looked like tiny rakes to eat, apparently fascinated by their knives and forks. He also noted that they did not touch the sashimi, and that they preferred drinking mirin to shōchū or sake (while mirin is principally used for cooking today, it was a common drink at the time). There are also records of the gifts brought by Perry. He presented musical instruments, weapons, agricultural tools, telegraph equipment, perfume, alcoholic beverages, furniture, and other items to the shōgun, daimyō, and their retainers. There are also picture scrolls showing these goods, indicating the great interest in Western products among the Japanese.

Commodore Matthew Perry and his men arrive at the banquet in Yokohama. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

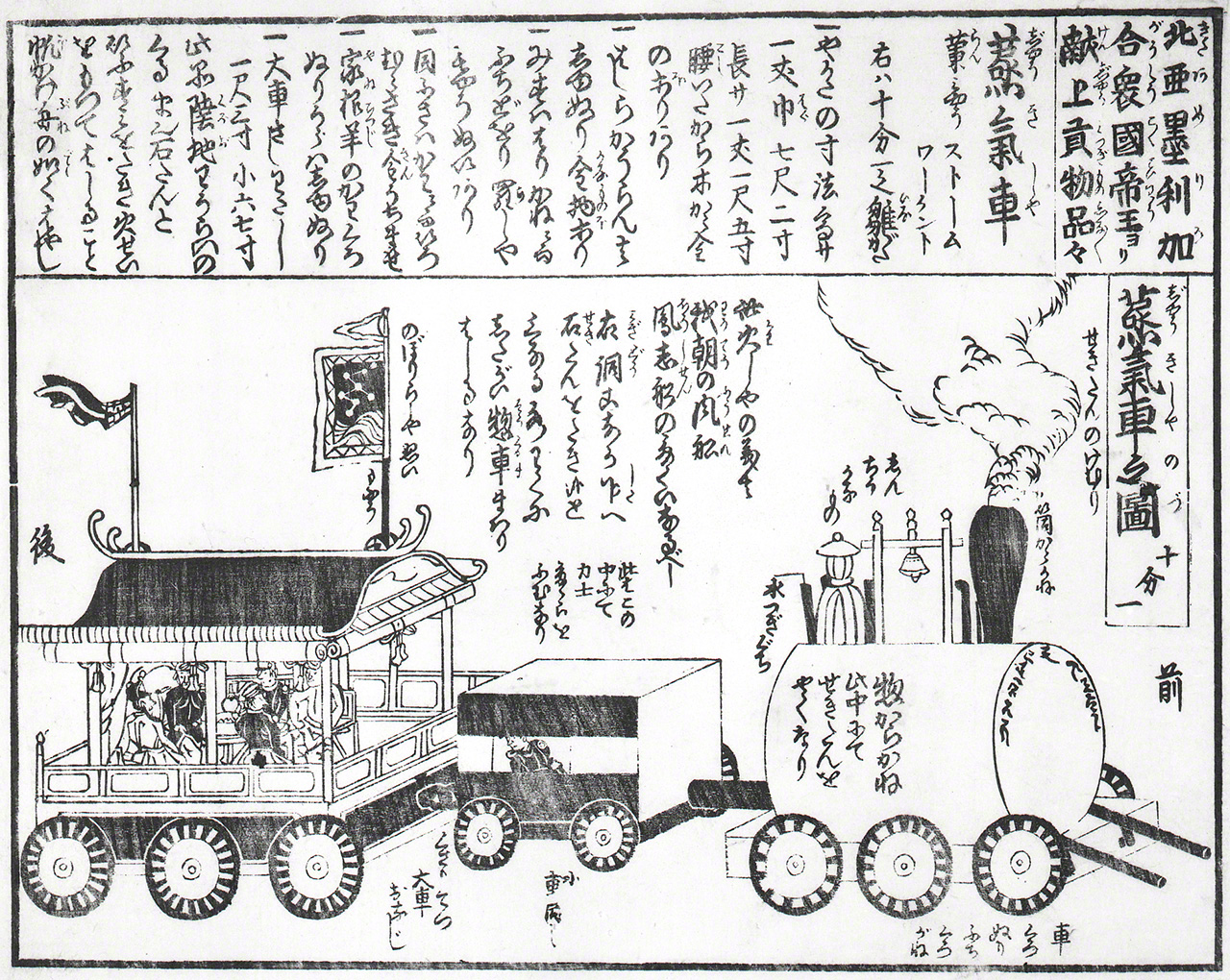

Perry brought a model steam locomotive to show off American industrial prowess. In its speed of around 30 kilometers per hour and the black smoke it puffed out while on the move, it was no different from the larger locomotives it was based on. Perry had a circular track of around 100 meters laid out near where negotiations were being held, and crowds gathered to watch the demonstration. The carriages were only around large enough to carry a six-year-old child, but it seems some of the watchers climbed on the vehicle as it traveled around the track. A record of the Perry expedition described the “ludicrous” spectacle of a shogunate official clinging to the roof and “grinning with intense interest.”

A kawaraban newspaper reporting on the gift locomotive. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

Infotainment for Edoites

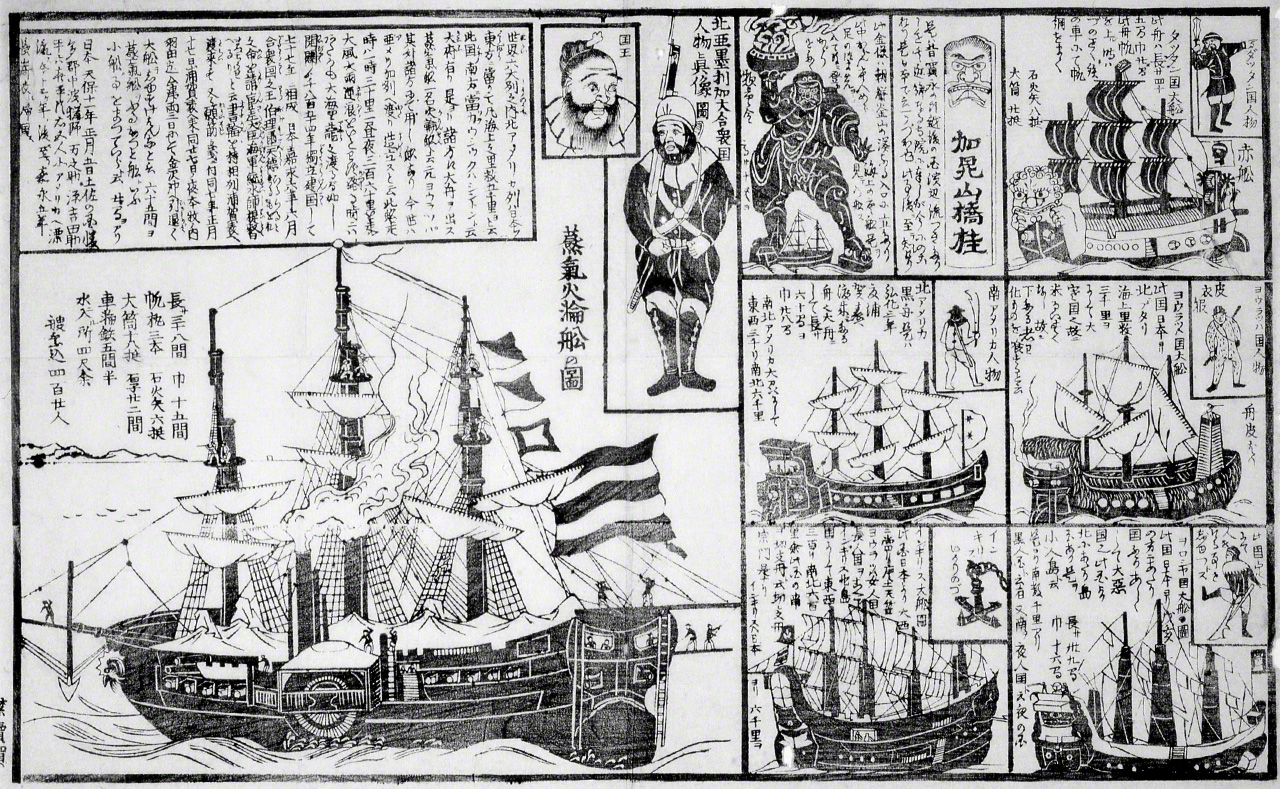

From 1853 to the following year, many kawaraban, or single-sheet woodblock prints, were published in Edo. These were a key source of news to the citizens, in an infotainment style similar to today’s televised “wide shows.” The first kawaraban to cover the black ships included words and illustrations to convey the size of the vessels and the number of cannons they had, as well as the defenses of Tokyo Bay and how daimyō were making preparations in other areas. Some showed soldiers on the move from Edo to strengthen defenses elsewhere, and these sheets with samurai in armor and helmets were quickly snapped up by avid readers.

Kawaraban depictions of the US vessels. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

They also provided information about how the United States had declared independence from Britain in 1776, and that its capital was Washington. While there was certainly some misinformation, in general the common people of Edo were able to learn more about the United States and Perry’s fleet via the kawaraban.

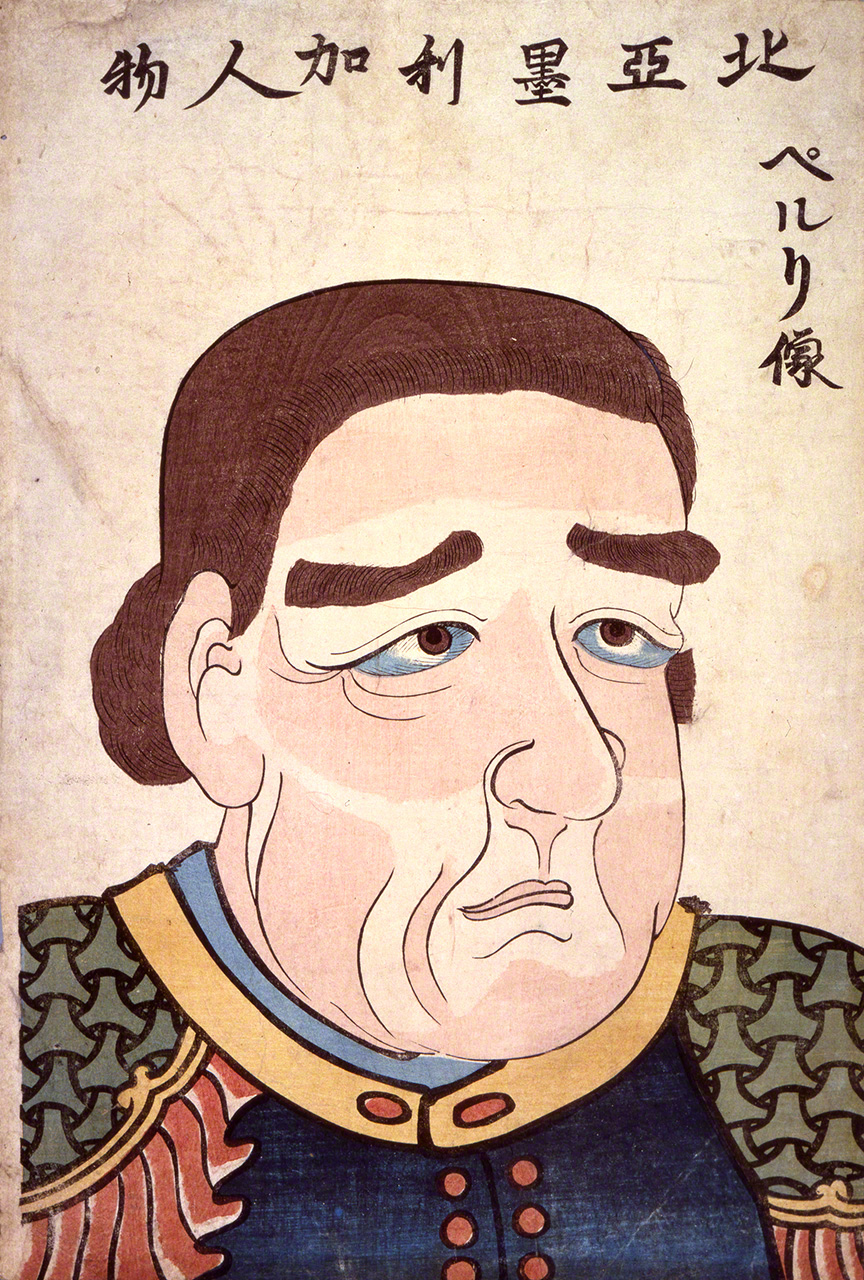

Perry, as depicted in a kawaraban. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

With the start of treaty negotiations, the kawaraban switched their focus to interactions between crew members and the Japanese in Yokohama. One gave highly accurate descriptions of the menu at the banquet for the Americans. For example, it said that the namasu, a dish of finely sliced fish seasoned in vinegar, used abalones and blood clams, and that there was gobō (burdock root) and udo (Aralia cordata) in the soup. It also noted that other dishes included mutsu (gnomefish) roe, tōfu boiled in dashi, and grilled sea bream. While the piece does not mention a source, the writer may have asked a shogunate official.

An Edo store selling kawaraban about the black ships. From Kurofune raikō fūzoku emaki (Picture Scroll of Customs Around the Arrival of the Black Ships). (Courtesy Saitama Prefectural Museum of History and Folklore)

The kawaraban reported on the presents exchanged by Perry and the shogunate, and a sumō demonstration at a reception held in Yokohama. The shogunate wanted to show the Americans, who included many well-built officers, that there were also large Japanese, but the Perry expedition record showed a dismissive attitude to the wrestlers: “They were all so immense in flesh that they appeared to have lost their distinctive features, and seemed to be only twenty-five masses of fat.”

The rikishi depicted in the kawaraban, performing feats of strength. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

Dozens of different kawaraban were published after Perry’s fleet arrived, with each one said to have run to around 1,000 copies. This is a tiny number compared to newspaper circulation today, but the total printed in a short period was unprecedented in the Edo period (1603–1868), and they gave people a detailed picture of the treaty negotiations.

A Fundamental Transformation

Reports grew in precision the longer the US fleet was present. For example, when the vessels first arrived, they were only described as “foreign ships” or “black ships,” but this later became “US ships.” The word ijin or “foreigner” also became less common, and profiles appeared of a number of individual Americans.

Meanwhile, Luo Sen, a Chinese interpreter working for the US fleet, recorded in his journal that a shogunate guard suggested it was a degradation for him, as a highly educated Chinese man, to speak the language of a barbarian country like the United States. This shows the guard’s surprise that a Chinese person would be employed to interpret for Westerners, and may have shaken his sense of respect for the Chinese. There is also a record by an Edoite of how the black US crew members carried out dangerous tasks like cleaning the bottoms of the ships.

The appearance of Perry’s fleet was an unignorable sign for Japanese society of the Western powers’ advance into Asia. It also conveyed a message that there were different nations and races in the world, and white people were at the top. It would be some time before Japan set its sights on modernizing to stand alongside the West, but it goes without saying that the event fundamentally transformed the thinking of Japanese people.

Commodore Perry Coming Ashore at Yokohama, attributed to Wilhelm Heine. (Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History)

(Originally published in Japanese on January 6, 2023. Banner image: The USS Powhatan, the flagship of the US fleet. Courtesy Yokohama Archives of History.)