Undiscovered Treasure Lures New Residents to Ama, Shimane

Society Work Economy Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Against All Odds

The town of Ama is a remote one, located on the island of Nakanoshima in Shimane Prefecture, four hours from the mainland by ferry from Sakaiminato in Tottori Prefecture. Alternatively, it is one hour by ferry from Dōgo, the largest of the Oki Islands, which is just a 40-minute flight from Osaka’s Itami airport. Ferries are often canceled due to rough seas, a common occurrence in the autumn and winter months.

The islands have a reputation for being distant and isolated, known for being the exile location of Emperor Go-Toba in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). They are wildly beautiful, with a pristine natural setting. Surrounded by crystal clear seas, and with a dramatic geography, the Oki Islands are listed in the UNESCO Global Geoparks Network. Here and there on the rugged islands, the mountains suddenly open up to reveal rice paddies.

A view from Nakanoshima toward Chiburijima, at left, and the peninsulas of Nishinoshima at right. (© Mochida Jōji)

Rice paddies sit adjacent to woodlands. (© Mochida Jōji)

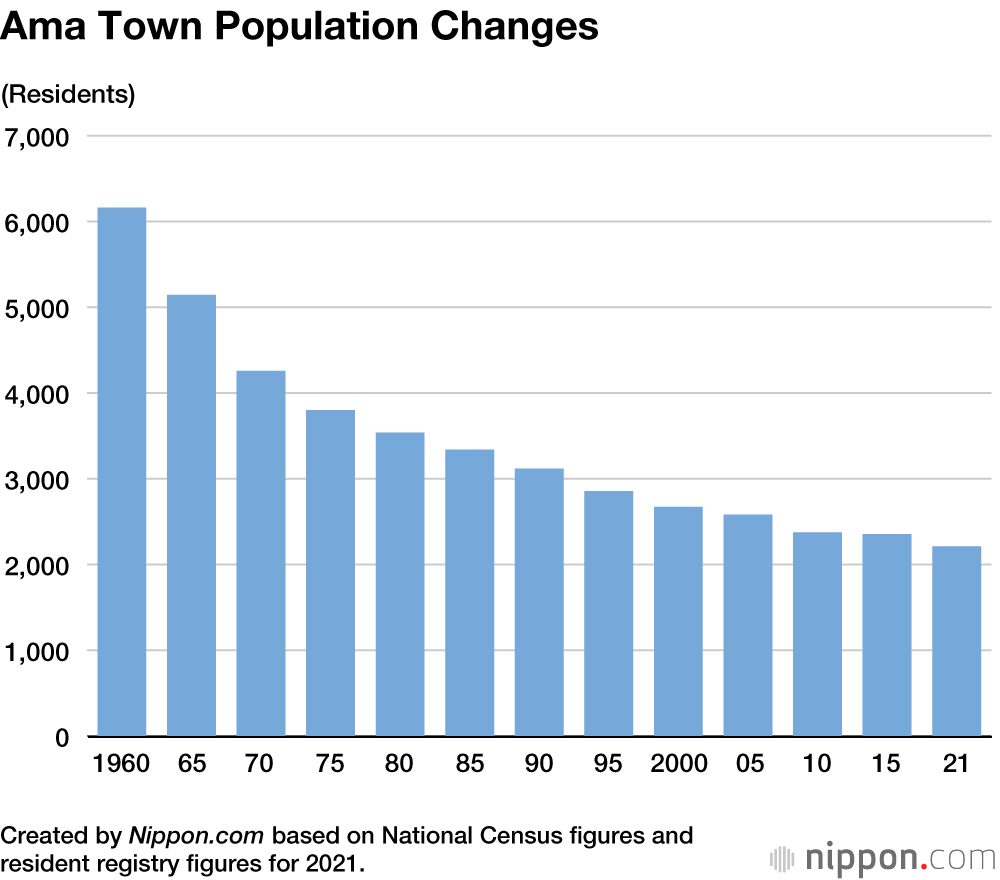

But are such remote islands destined to decay? Ever since World War II, young people have left the islands never to return, and the population has continued to decline. Public works projects helped prop up the islands, but ballooning debt, straining government finances, has backed the islands up against the wall.

Seeking Independence

Amid the town’s economic woes, Yamauchi Michio, a town councilor determined to bring reform, was elected mayor in 2002. In 2004, he launched a plan to promote independence, for the town’s survival. He introduced drastic staffing cost cuts in the town hall, redirecting money to add value to local industries such as fisheries and the livestock industry, and to boost child support.

In 2018, Ōe Kazuhiko, who had worked in the town government’s industrial development division under Yamauchi, became the new mayor. Reflecting on Yamauchi’s mayorship, Ōe says, “All the town hall staff, not just the officials, offered to take salary cuts, as an investment in the town’s future. I think that the town hall’s determination rubbed off on the island’s residents.” Townsfolk began to appreciate them more, and became more receptive toward reform.

Ama’s mayor Ōe Kazuhiko. (Courtesy of the Ama municipal government)

If cutting staff costs was a “defensive” move, it was the “offensive” of administrative reform that caught the eye of outsiders, enticing them to dig deeper to uncover the town’s hidden potential—the “treasure” of the Ama township that could be developed into products of real value. “We were sitting on an untapped goldmine, but had trouble recognizing its value ourselves.” Ōe explains that it was outsiders who made such discoveries.

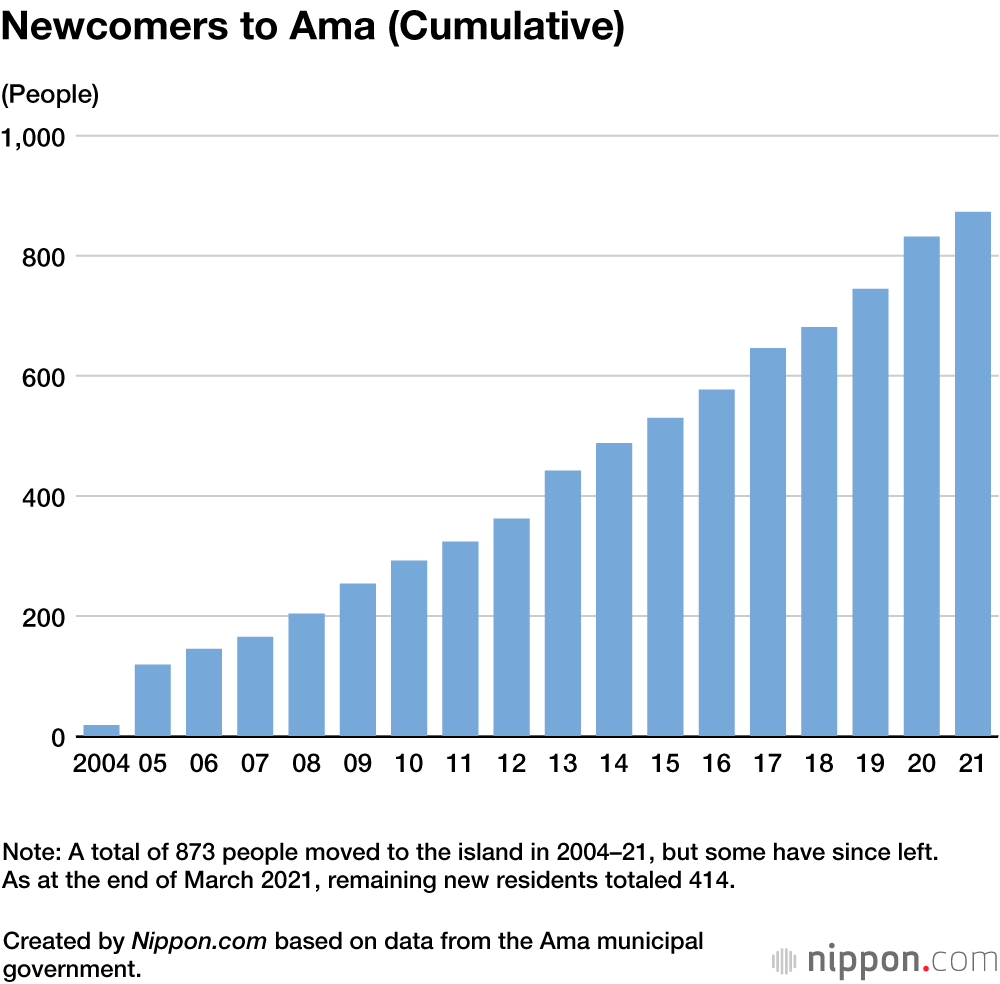

Product development trainees—Ama Town’s regional development corps—were the initial key players. Later, the town vigorously advertised on job posting sites seeking people who wanted to use their abilities for the town. Their efforts began to pay off, and newcomers started arriving in Ama. The town provided new residents with childcare benefits and housing, predominantly funded with money saved by the pay cuts taken by town hall officials.

People love the chewy texture of the sazae turban shell curry (left), developed by the product development trainees, and Oki’s renowned beef (right). With the decline in public works, a local construction company has entered the livestock industry. (© Mochida Jōji)

Housing for new residents. (© Mochida Jōji)

Treasure Hunting

Ishida Daigo, now 42, was among the first wave of new residents, moving from Osaka in 2005. After he became disillusioned with the business practices of his old company, he found himself intrigued by a job board posting looking for “people to seek the island’s hidden treasure.”

The position advertised was at a marine product processing facility that used quick-freeze technology to maintain freshness. Ama’s seafood industry was hampered by the cost of transporting products to Tottori’s Sakai Port, and issues with freshness often resulted in lower prices. A joint venture between government and business, designed to benefit the town, had introduced new technology to turn the local oysters and squid into big sellers.

The marine product processing facility uses a “cells alive system” to freeze squid instantaneously. (Courtesy of the Ama municipal government)

The venture uses CAS, or “cells alive system,” instant-freezing technology to boost the value of the squid almost three-fold. According to Ishida, it was a straightforward operation, but each task performed was helping to rejuvenate the town, and he was proud to tell his friends about it. “This is probably my treasure.”

Dried sea cucumber is another treasure uncovered by a newcomer. In 2005, Miyazaki Masaya, then a student at Hitotsubashi University, was involved in an exchange project with Ama’s junior high students, leading him to become enamored with the town. He eventually rejected a job offer from a financial institution and moved to Ama to work in the fishing industry. Inspired by his prior experience studying in China, he realized that dried sea cucumber, a luxury ingredient in Chinese cuisine, could be produced in the town and exported to China, resolving the undervaluing of the town’s precious harvest.

But there were no facilities to dry the catch, and even with a national government subsidy, Miyazaki and his comrades still needed ¥70 million in funding from the town. Ama’s fiscal 2007 budget proposal was met with fierce opposition in the council. Ōe, who was then responsible for industry promotion at the town hall, went to lengths to explain that, if the project succeeded, it would bring significant income from China. By demonstrating that the extra money would be shared with the local fishers, thus providing everyone with greater income, he finally convinced the council to pass the budget. Sea cucumber is now a valuable source of income for the town.

The Tajimaya brand sea cucumber plant. (Courtesy of the Ama municipal government)

Stories from the first posse of new residents spread by word-of-mouth and on social media, drawing more young people hoping to follow in their footsteps. From the introduction of the reforms in 2004 up through 2021, the town enticed a total of 873 newcomers. Of those, 414 have remained, representing 18.7% of the population of 2,212 (as of the end of March 2021). Not only has the town managed to stem its depopulation trend, it has also lowered the average age.

As the town faces a succession dilemma owing to its aging population, newcomers are valuable in a range of fields, and locals accept them as their own. According to Ishida, “Everyone is cooperating as a team. Everybody wants to work together, to repay their gratitude to the island.” Many people moved to Ama on a whim, but already they feel like true islanders.

The Toyoda fishing harbor in northern Ama. (© Mochida Jōji)

Half Government Official/Half X

One example of this new wave of residents is Kojima Megumi. According to her business card, her position is “Half Government Official/Half X” in the Ama Town Council’s Exchange Promotion Division. She explains that the “half X” indicates that, for the sake of the community, she can perform any role. “I’ve even changed sheets and done the ironing at Ama’s Entō Hotel.”

This symbolizes the revolution that has taken place among Ama’s public servants. It also incorporates a philosophy espoused by Mayor Ōe: “Don’t think that your job is to just sit behind your computer and do work dictated by the national or prefectural governments. The challenges we face are at the frontline, and we should take the initiative to benefit the town.”

Kojima Megumi and her unusual business card. (© Mochida Jōji)

Kojima moved to Ama from Kanagawa Prefecture in April 2022. With the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work had become well-accepted, to the point where one could work for an office in Tokyo while growing grapes to make wine.

Recently, the town has been expanding its efforts beyond just seeking new residents, designing other avenues of loyalty. Supporters of Ama can be anywhere, but are encouraged to have financial ties with the town, for example, by purchasing local products, or through the furusato nōzei (hometown tax) system. The town also hosts adult “exchange students” for 3 to 12 months, to familiarize people with the island.

As it faces an aging population, a declining birthrate, and waning vitality, Ama is a snapshot of Japan’s future. Toyota Shōgo is the town council’s special representative for developing human resources. In his view, “Inconvenience begets wisdom. Our challenge is to become a model for the future of Japan.”

Ama now receives frequent visits from representatives of other local governments that are struggling with depopulation. Here, representatives from the village of Ogasawara, a remote island outpost in Tokyo, meet with Toyota Shōgo (in blue, at the desk at front) to learn about Ama’s strategies. (© Mochida Jōji)

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: The view from Rainbow Beach in Ama. © Mochida Jōji.)