Medical Care Behind Bars: Author Ōtawa Fumie on Being a Prison Doctor

Society Health- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Treating the physical and mental ailments of prison inmates is the role of a team of prison doctors employed by the Japanese Ministry of Justice’s Correction Bureau. These doctors practice what is known as correctional health care. Their number is constantly fluctuating: As of 2022, a mere 291 doctors staffed Japan’s 73 correctional and detention facilities. Prison doctors are posted to penal institutions around the country, and while most are employed as full-time public servants, others work as itinerant doctors, visiting different institutions on different days.

“I’m an itinerant doctor responsible for three institutions,” explains Ōtawa Fumie, author of a new book on the profession—“a prison, a youth justice facility, and a remand center, all located in Kantō and other outlying areas nearby. My patients comprise a wide variety of prisoners including murderers, rapists, abductors, firearms offenders, drug addicts, and even juvenile inmates. While I refer to my patients as ‘inmates,’ some of them are actually in remand centers awaiting trial.”

A Clinic “On the Inside”

Many patients want to be seen by a doctor. Nurses perform regular rounds in which they inquire after the health of the inmates. “Many of these nurses actually started out as warders and later trained as nurses so they could perform both tasks,” says Ōtawa. “There are therefore some very muscular male nurses. Male inmates are usually accompanied by a male nurse in case there’s a struggle or unforeseen circumstances arise.” Sometimes an inmate will fake an illness in order to see a medic, she explains, but if a nurse decides that an inmate should see a doctor, he or she is brought to consultation. Prisons employ internal medicine specialists, psychiatrists, and sometimes even orthopedic surgeons, optometrists and dentists. Prohibited from talking to each other in the waiting room, inmates must sit in silence, facing the wall.

“The clinic is staffed by several warders and nurses, so we’re never left alone with patients. There are several desks, and sometimes several doctors examine patients simultaneously. In a regular outpatient clinic, there is one consultation desk in each room, and the doctor and the patient are left alone. But in our workplace, that doesn’t happen.”

To prevent the medical workers’ personal information from falling into the hands of inmates, who might be tempted to look a person up once they are released, the doctors and nurses at the clinic do not call each other by name. “Nurses won’t refer to me as ‘Dr. Ōtawa,’” the author explains. “Instead they’ll direct the inmate to, for example, ‘the doctor at the desk in the middle.’ There’s also a line drawn on each desk that inmates are not allowed to lean over.”

While electronic medical records are now the norm outside penal institutions, the overwhelming majority of Japanese prisons still use paper. Things are done the old-fashioned way, and there is a space that you would not find on a regular medical record for entering information on unusual traits such as tattoos, missing fingers, and wounds. Also, above the description of the patient’s illness, there is always information on what they are in for, their number of offenses, when they were incarcerated, and when they are due for release.

“As a prison doctor, I see fourteen or fifteen patients in a morning session. On the outside, I would sometimes see fifty outpatients in a morning, so the caseload in prison is not that high. That doesn’t mean I can spend longer with each patient, however. Prohibited from making chit-chat, the patients only talk about matters relevant to the consultation. I like to make jokes and talk about a range of topics. After all, that is all part of the process of treating a fellow human being, and I try to spend at least a few minutes on small-talk.” Unfortunately, says Ōtawa, if a patient’s answer to a question goes on too long, the nurse steps in to cut things short.

Why Become a Prison Doctor?

So why did Ōtawa choose this career? “My father was a doctor with his own practice, and it was out of a sense of duty and to meet the expectations of those around me that I went to medical school and became a doctor too. However, I was always pestered by the idea that I didn’t know why I had chosen this career. One day, an acquaintance asked me if I’d be interested in working in a prison. The idea interested me. The representative from the Justice Ministry was so earnest in inviting me to come and see the clinic that I agreed. After seeing the operation first-hand, I decided that I would be suited to the job. Without hesitating, I told the official that I’d take the job. He was completely taken aback, as this wasn’t what he was expecting to hear. And just like that, I had a new job.”

The reason Ōtawa thought she would be a good prison doctor, she recalls, is that did not find the job remotely scary. “People often ask me whether it’s frightening being ‘on the inside,’” she notes. “In fact, going to see the clinic and seeing inmates waiting to be seen by a doctor made me realize that the relationship between doctor and patient is no different from on the outside. These situations will cause some people to experience fear or discriminatory or negative emotions, but not me. I think the doctors that have that kind of positive reaction are precisely the ones who should work here.”

Doctors’ Shortage an Issue

She did not feel particularly scared after beginning her work as a prison doctor, either. “One of the patients I saw today was missing an eye and completely missing a finger. Many patients are in organized crime gangs. Because they lived bound by the rules of their organizations, though, they are used to being governed by rules. On ‘the inside,’ they’re mild-mannered and well-behaved as a result.”

The greatest issue faced by prison medicine is a shortage of doctors, says Ōtawa. While staff shortages in urban areas are at last starting to be resolved, regional locations still face significant shortages. It is a sorry state of affairs when a facility that houses several hundred inmates can go for days without having a single doctor on duty, and Ōtawa stresses that there needs to be improvement in these kinds of areas.

There are other problems to address as well. “Because of budget limitations, storage space is limited, so we can also only stock a small number of medicines. No prisons have MRI machines, and even CT scanners are rare. When it’s deemed necessary, we do send inmates to outside hospitals, but because this involves removing the inmate from the prison, the process requires several warders and a transport vehicle. The time-consuming red tape involved means that it can unfortunately take a long time to diagnose a single illness. It really strikes me that even on the inside, doctors must ensure they diagnose their patients illnesses before it is too late.”

Some readers of Ōtawa’s book may feel that these patients don’t deserve proper treatment because they are prisoners. But she disagrees vehemently. Care is thorough as can be: When inmates first come in, they are examined by a doctor, and at their annual physicals, they are x-rayed and undergo blood tests.

The Role of Correctional Medicine

Because inmates are sentenced to time with labor, they must be made to work. For this reason, she says, “We ensure they stay physically and mentally healthy. This is important in order to reduce the rate of repeat offending as well. In recent years, we are increasingly learning that harsh punishment does not reform prisoners, and the correctional process is starting to change. We know that we can reduce recidivism by concentrating on education and support for those being reintegrated into society.”

Ōtawa Fumie in the Nippon.com office in Toranomon, Tokyo. (© Amano Hisaki)

In areas of the prison outside the clinic, for example the workplaces and living quarters, conditions remain uncomfortable. Group living is stressful, and some of the warders can be very strict. They shout at inmates for talking back, and failure to comply results in punishment, with those who struggle being placed in solitary confinement. “The prison clinic is in fact the most peaceful part of the prison,” notes Ōtawa. “I think that’s one reason why inmates want to see doctors.”

At the clinic, says the doctor, inmates can tell the medical staff where they hurt, or what’s bothering them. “I believe the biggest job of a prison doctor is telling inmates that they are somewhere where they will be listened to—not that they have no right to complain because they did wrong. The message I most want to convey is that if the society on the outside refuses to accept former inmates and treats them like pariahs, they will have nowhere to go. Recidivism is not an issue that can be solved ‘on the inside.’ There also needs to be somewhere on the outside for former inmates to go. I believe it’s the community as a whole that enables criminals to change.”

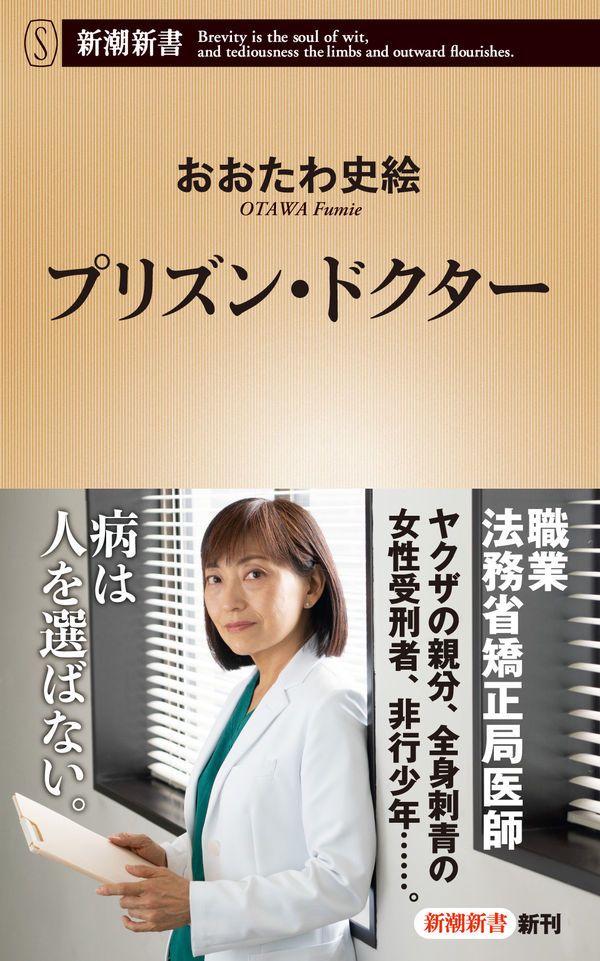

Purizun dokutā (Prison Doctor)

By Ōtawa Fumie

Published by Shinchōsha in 2022

ISBN: 978-4106109751

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Ōtawa Fumie in the Nippon.com office in Toranomon, Tokyo. © Amano Hisaki.)