The Former US Air Force Lawyer Assisting Women and Children in Okinawa Abandoned by US Servicemen

Society Family Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Plight of Local Mothers

“Children cannot choose where they are born. I believe my role is to recover the rights that have been taken from them, because I know how to do that.”

Annette Eddie-Callagain first encountered the child support payment issue 30 years ago. When she was working as a lawyer for the US Air Force at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, she learned of cases in which local women who had had children with soldiers and other men working for the US military were unable to receive child support payments. As the fathers were no longer in Japan the women had no redress, leaving them confused and overwhelmed.

In the United States there is a system that ensures the parent who is not raising the child or children pays child support. “Parents have the same responsibilities to their children no matter where they go,” said Eddie-Callagain, recalling the anger she felt at the time. “How could this irresponsible behavior be allowed to go on?” But providing legal support to mothers seeking child support from absentee partners would have required her full commitment and all her resources, something she was unable to do at the time. So she resolved to return one day to Okinawa to take on the issue.

Eddie-Callagain during her time at Kadena Air Base, around 1991–2. (Courtesy of Annette Eddie-Callagain)

Some 70% of the US troops stationed in Japan are in Okinawa, and 60% of these are in the Marine Corps. The US Marine bases in Okinawa are largely used for training and military exercises, and new recruits in their late teens and twenties are sent there on rotations typically lasting several months. Many of them spend their free time off base, where they meet local women. Although children may result from these relationships, the US servicemen are soon transferred to other bases. In many cases the local women lose touch with the fathers of their children, and often both the mothers and the children face dire circumstances, both economically and socially.

The women who are raising children fathered by “Americans from the base” are not viewed with understanding and empathy by those around them. “Women who work in bars, restaurants, and convenience stores in the towns near bases frequently encounter US servicemen. That has become the norm in Okinawa,” says Noiri Naomi, associate professor of humanities and sociology at the University of the Ryūkyūs. “While this situation may be a result of ‘free love,’ individuals’ lifestyles are closely entwined with the social structure.”

Callous Attitudes of Absentee Fathers

A screencap from a remote interview with Eddie-Callagain in March 2023. (© Gotō Eri)

Eddie-Callagain returned to Okinawa as a civilian in 1995. Her application to register as a foreign lawyer in Japan was approved, and she opened a law office. She was soon contacted by a local single mother to schedule a consultation. The woman was raising two children fathered by a US serviceman.

Her former husband left home to “have a job interview,” as he explained to her, but never returned. She called her in-laws in the United States to try and find out where he was, and it was then that her former husband told her he wasn’t coming back to Okinawa. As their four-year-old son was deaf, the local woman was learning sign language in order to communicate with him and was unable to work full time as a result.

Eddie-Callagain called the former husband and informed him that if his former wife did not learn sign language she would be unable to communicate with their son. If he felt that he didn’t want to provide support in spite of this, they would bring him to court. In response, the former husband said that since he was in the United States and they were in Okinawa, there was nothing they could do to him. This statement gave Eddie-Callagain the resolve to do whatever needed to be done.

“I will not give up until I make this man fulfill his responsibilities as a father,” she remembers thinking.

During her search for a way to collect child support payments from US servicemen residing in the United States, she was referred to the annual training session held by the National Child Support Enforcement Association, an organization that provides training to child support professionals. She joined NCSEA and traveled to the United States each year to attend the annual training conferences out of her own pocket. This allowed her to build relationships with representatives of the organization from every US state. She learned that she could apply for child support services, to collect monetary benefits from an absentee father, even from Okinawa as long as the child support office of the state in which the father resides accepted her application for assistance.

“Once I got to know the person in charge of the child support office located in the state where the absent father resided, I could inform him or her directly of the situation. And then all it takes is a little enthusiasm,” she says with a laugh.

Success in 35 States

At the first NCSEA training conference that she attended, she met representatives from the Illinois child support office, the state where the absentee father mentioned above was living. In 1998 the state ordered him to pay child support. This was the first successful case of a child support payment collection from Okinawa. She then hired a full-time staff member who spoke Japanese. She worked the first few years for free in spite of each case costing several thousand dollars. At the start of each new case, she would persistently negotiate with government officials in the state where the absentee father was living. To date, she has been able to obtain child support payments from 35 of the 50 US states.

The United States has a powerful legal system in place to ensure payment of child support. Once it is determined that he is the father, he must pay the amount of child support determined by the court until the child reaches the age of adulthood, which is 18 in the United States. If he is late in his payments or fails to pay, the state government can suspend any occupational license he has, put a lien on his bank account in order to force payment, and so forth. If a man does not recognize a child as his own, he is forced to undergo a DNA test to establish parenthood.

At home in New Iberia, Louisiana. (Photo courtesy of her son, Glynn)

However, some states refuse to take on cases from mothers residing in Japan due to the lack of a mutual agreement regarding child support with the Japanese national or local governments. Thinking that she would be able to make smoother progress if there were an official memorandum on the issue, she proposed to the prefectural government of Okinawa that it sign memoranda of understanding with US state governments. The Naha government, however, seemed to be reluctant to act, replying simply: “There are already systems in place for single parents, such as allowances for dependent children and support allowances.”

“Raising children is the responsibility of both parents,” says Eddie-Callagain. “And since the child support payments coming in from fathers in the United States are in dollars, it’s not like Okinawa is suffering a loss of any kind.” But she was at the same time aware of the complex attitudes that the people of Okinawa have toward partners and children left behind by US servicemen. One of her Okinawan clients was told not to bring “a child with different-colored skin” to the grandparents’ house. Such women often have nowhere to live and no one to help them.

The Best Interests of the Children

“Annette doesn’t see the issue as either the United States or Japan, or as either the father or the mother, as being the one to blame,” says Han Kyōko, a Japanese-language teacher who works as an interpreter at Eddie-Callagain’s law office. “She is angry at fathers who do not fulfill their responsibilities, and at the same time she tells mothers that they need to take better care of themselves and that they should have both a sense of responsibility and of dignity.” Eddie-Callagain does not accept cases in which the custodial mother who is demanding child support payments refuses to let the father exercise his visitation rights without justification. She has tirelessly gone out to offer explanations of the relevant systems, whether it be to parties in the US military or to local groups that oppose the military presence in Okinawa. What must be done is what is fair. What is in the best interests of the children. Eddie-Callagain has prevailed in nearly 800 cases of failure to pay child support through the application of these unwavering beliefs.

Another mother who was assisted by Eddie-Callagain is Fukami Tomoe, who works at a base in Okinawa.

She met a serviceman in the US Navy, married, and gave birth to their daughter at the age of 27. But her husband left for his next assignment before their daughter was born. He failed to regularly send money even while they were still married. They were eventually divorced due to the fact that they were living apart and to differences in their living circumstances impacting their relationship. She attempted to collect child support by telephoning government agencies in the United States, but was given the runaround as she was told each time that such claims were not within their jurisdiction.

“Getting divorced takes much more energy than getting married,” says Fukami. “I thought I would explode due to the anger and frustration, not to mention the stress of raising a child.”

At the same time, however, raising her daughter was her one motivation to go on living. She sent her to an international school as she wanted her to be “proud of her dual heritage.” She worked tirelessly to earn the money to pay for the school tuition and their living expenses. Eddie-Callagain said that she would represent Fukami in her efforts to claim child support. “I couldn’t believe that someone would help me at no cost,” says Fukami. “She is like an angel.”

“Paying It Forward” by Seeking a Career in the Law

With Eddie-Callagain’s assistance, she was able to achieve a ruling from the state government ordering her former husband to pay child support in an amount equivalent to between $300 and $380 per month until her daughter reaches the age of adulthood. “This money is important to my daughter,” said Fukami. “I saved all of it to pay for her university tuition.” Her daughter studied criminal law at the University of Hawaii and plans to go into the legal profession like Eddie-Callagain.

Eddie-Callagain has not helped only women. Approximately 10 years ago a Japanese man in his fifties repatriated his children to Japan after winning a US court case against his American wife who had made off with the kids to the United States from Okinawa. Eddie-Callagain spent several months assisting the man with everything from preparing his statements to representing him in court. After his children had been repatriated, she even took care of them when she thought he might be having a tough time due to his dual work and child-rearing responsibilities. “Without her,” the man said, “we never would have been able to put our family back together. We owe her everything.”

“I Never Once Thought of Giving Up”

Upon entering the Navy in 1983. (Courtesy of Annette Eddie-Callagain)

Eddie-Callagain is from the American South, where discrimination remains a persistent problem. She grew up in a single-mother home as the third of 10 siblings. Her mother worked as a maid in a white household and did not have the means to hire a babysitter, and so during long school breaks, she would bring the children to the public gallery of a local courthouse, where they were guaranteed a safe, calm environment. “The prosecutors and lawyers were all white,” she says, “while most of the defendants were black. I just thought that was the way things were.”

She worked hard during her university days, pursuing her studies while working part time on campus, and became a high school teacher. One day she was invited to a graduation party being held for a colleague’s friend who had completed her studies at law school. “When I arrived at the party, I saw that the law school graduate was a black woman just like me,” said Eddie-Callagain. “It was the first time I realized that a black person could become a lawyer, and this realization changed everything for me.” She left her teaching job, entered law school on a scholarship, and graduated with excellent grades. While studying for the bar she herself was a single mother who was struggling to balance studies with both her job and her responsibilities to her child. “I couldn’t allow my son to become homeless,” she said. “I never once thought of giving up.”

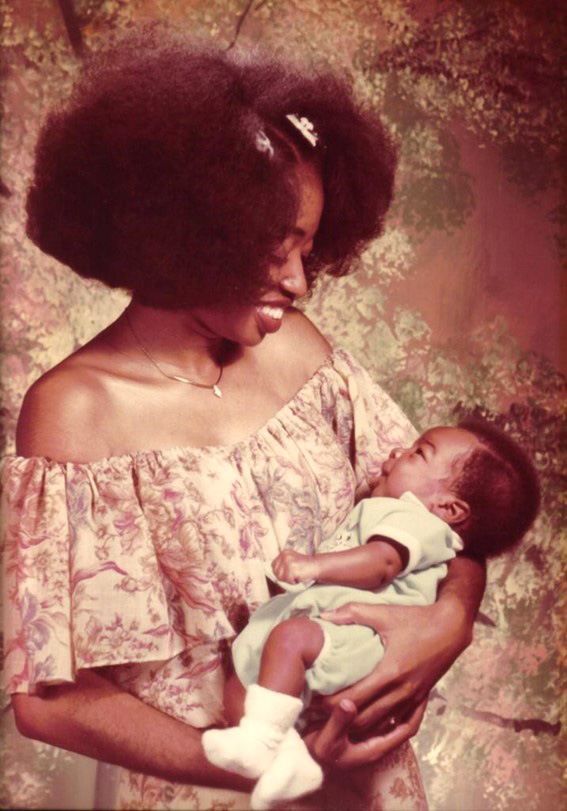

With her newborn son in 1979. (Courtesy of Annette Eddie-Callagain)

With her son, Glynn, at a school reunion in 2018. (Courtesy of Annette Eddie-Callagain)

Eddie-Callagain has been working to support parents in Okinawa seeking child support for 28 years. As there is still no consultation service staffed by qualified people who are knowledgeable in the pertinent aspects of the legal system, she is still inundated by inquiries. “It has become shockingly easy for people to meet now as a result of the widespread use of dating apps,” says Han, Eddie-Callagain’s secretary. “As a result, we are seeing an increasing number of inquiries from pregnant women who only know the father’s dating app nickname. So, there is still a great need for the kind of services Annette provides.”

Eddie-Callagain has since returned to the United States, but she will continue providing her legal services to the people of Okinawa via a website she is currently setting up.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Eddie-Callagain photographed by her son, Glynn, near her home in New Iberia, Louisiana. Courtesy of Annette Eddie-Callagain.)