“Shitaku beya”—Where “Rikishi” and the Media Meet

Sports- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Like a Dressing Room Backstage

The East and West shitaku beya, or dressing rooms, at Tokyo’s Ryōgoku Kokugikan lie toward the back of the arena. These long, narrow rooms, at the end of the corridors leading to the ring, are floored with tatami mats and feel like backstage spaces at a performance hall. The rooms are bare save for full-size mirrors and pillars for practicing the teppō pushing and thrusting motions that are fundamentals of the sport. Spacious bathing and toilet facilities are attached.

Rikishi, tokoyama hairdressers, and others connected with the Japan Sumō Association, as well as sports reporters and photographers with the proper credentials, can come and go as they please. But being part locker rooms and part press rooms, shitaku beya are where rikishi disrobe, and as such are off-limits to women.

The air in the shitaku beya becomes charged after two in the afternoon, when the top-division wrestlers enter and start preparing for their bouts. Dressed in formal wear of haori crested jackets and hakama overskirts and accompanied by their attendants, they come pouring into their respective dressing rooms. After donning their decorative keshōmawashi aprons for the ring entrance ceremony, they return to the dressing rooms to change into loincloths and begin warming up. They do shiko squats and practice their tachiai face-off moves, with their attendants standing in for their opponents. They slap and slam the teppō pillars and jam the narrow aisle as they practice suriashi, keeping their feet on the ground while squatting and moving forward. When the time for their match nears, they are escorted by their attendants through the corridor to the dohyō ring.

The space occupied by the rikishi in the dressing rooms corresponds roughly to their standing in the banzuke rankings. The ranking yokuzuna occupies the farthest end of the room, with other yokozuna and ōzeki on either side, and sekiwake, komusubi, and maegashira filling up the rest of the room by rank..

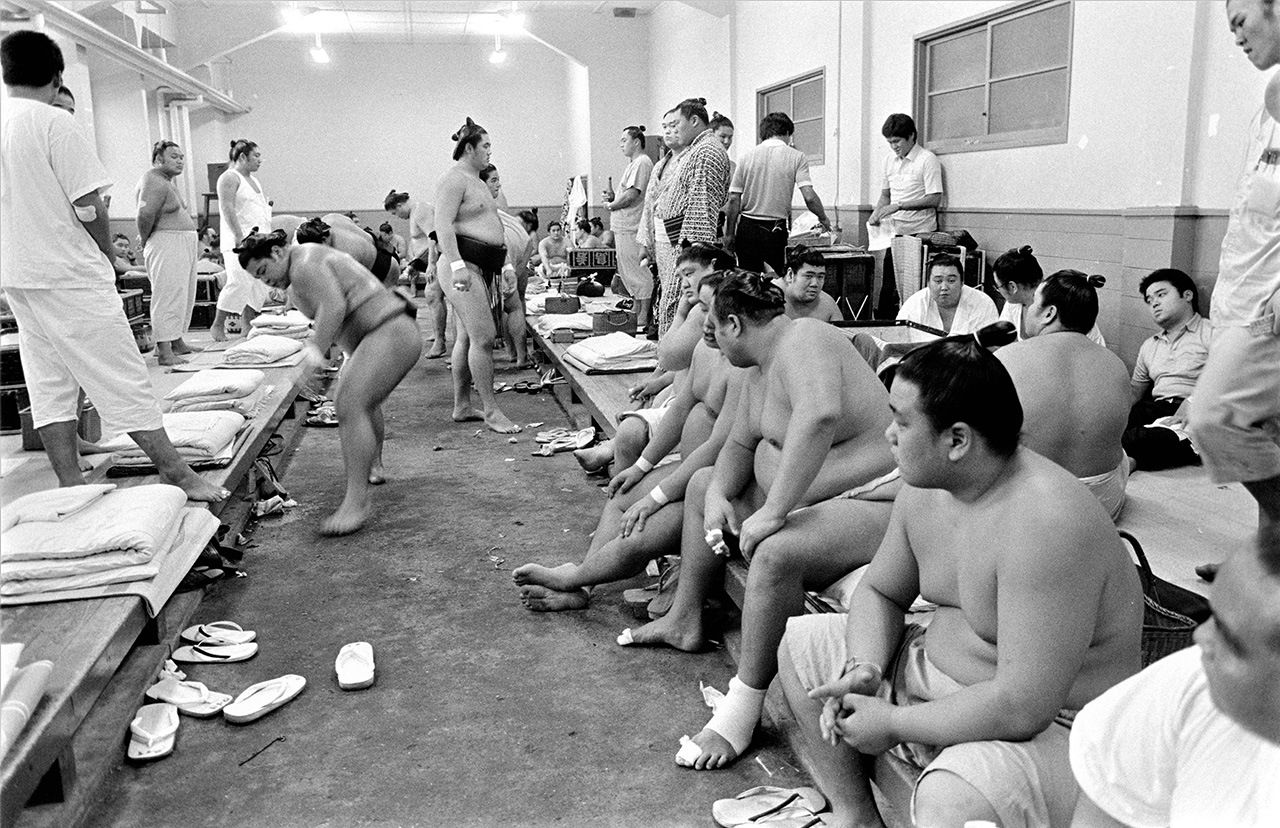

A shitaku beya at the Kuramae Kokugikan, where Tokyo tournaments were held until 1984. (© Jiji)

Best Timing for Interviews

After their bouts, rikishi return to the dressing rooms and bathe to clean off sand and sweat. They then sit to have their hair restyled from the elaborate ōichō coiffure worn by the top ranks in the ring to the plainer chonmage topknot. This is the optimum time for approaching them for interviews.

Numerous reporters flock to interview top-ranking and up-and-coming rikishi. It is not unusual for 20 or more reporters to cluster around a yokozuna, and anyone who wants to get a good quote makes sure to secure a front-row spot.

A grim-faced yokozuna Kisenosato, returning to the shitaku beya after his second consecutive loss on day two of the January 2019 tournament, with his attendant holding off the press. Two days later, Kisenosato announced his retirement. (© Jiji)

Places are not strictly assigned, but veteran reporters and those the rikishi know well stand to the side and in front. Reporters new to the sumō beat have to stand at the back of the crowd and crane their necks as they take notes. If a rikishi is soft-spoken, it can be hard to hear what he says, and reporters are often seen checking up with each other on the content of a wrestler’s comments.

The shitaku beya are equipped with television monitors relaying the NHK live broadcasts. Back in the dressing room after his match, ōzeki Dejima (now oyakata, stable master, Ōnaruto) watches the action with reporters including the author, at front row center. (© Nagayama Satoshi)

A Place Where Emotions Can Run High

Wrestlers who have won their matches are often in a good mood. Even so, some are men of few words. Losers, meanwhile, can be out of sorts and refuse to talk, or may be seething with anger. The sumō world is one of wins and losses—there are no gray areas—and defeats have a direct bearing on rikishi prospects for advancement. The dressing rooms see all sorts of mini-dramas playing out and can, in a certain sense, be more interesting than the matches themselves.

Mitakeumi, winner of the 2018 summer tournament, notched the first tournament championship for the Dewanoumi stable in 38 years and was the first title-taker to hail from Nagano Prefecture. (© Jiji)

Interviews with rikishi are a bit different than for athletes in other sports. Reporters do not ask questions about what is common knowledge, avoid digging too deeply, and phrase their queries so as not to displease the interviewee.

Since interview questions tend to be similar at each tournament, experienced reporters are on the lookout for a few words or a facial expression that can give some insight into what a rikishi is feeling. Before they get to ask any questions, reporters new to interviewing rikishi start out by assiduously attending morning practice sessions so that they become familiar faces. In the dressing rooms, some reporters are instructed by their newspapers to observe and learn from veterans’ interview methods.

Contrasting Styles

Rikishi reaching the top ranks of yokozuna or ōzeki, conscious of the responsibilities of their position, need to be cautious when speaking. Many upper-ranked wrestlers—for example, two ōzeki, Kotoōshu (now oyakata Naruto) and Takayasu—would stay virtually silent after losing a match.

At one tournament, Kotoōshū, skilled at uwatenage overarm throws, unexpectedly lost a match to his opponent, who used a shitatenage underarm throw. Reporters in the shitaku beya asked Kotoōshū a few questions, all of which were met with a “no comment.” One reporter made the notation “. . .” in his notebook. Spotting that, Kotoōshū said, “I didn’t say anything, so what are you writing down?” “Nothing in particular,” answered the reporter, but the leaden atmosphere in the room grew even heavier, with the wrestler and journalist glowering at each other for what felt like a long time.

Yokozuna Hakuhō, after losing a match to Gōeidō on the twelfth day of the May 2015 tournament. Hakuhō sits with his back to reporters, unwilling to be interviewed. (© Kyōdō)

Yokozuna Takanohana, an instigator of the Heisei era (1989–2019) sumō boom, was famously taciturn during his days as the up-and-coming fighter Takahanada. This was partly because as a member of a famous sumō dynasty—the son of an ōzeki, nephew of a yokozuna, and brother to another wrestler, Wakanohana, who also reached the top rank—he attracted so much frenetic media coverage. He was the same in the shitaku beya, uttering nary a word whether he had won or lost. When he lost a match, he would only say: “I lost because I was weak.”

On the first day of the May 1991 tournament, Takahanada (later Takanohana) faces the press in the shitaku beya after downing yokozuna Chiyonofuji. At the age of 18, he was the youngest wrestler ever to defeat a yokozuna, but even so he remained tight-lipped and expressionless throughout the interview. (© Jiji)

Never previously voluble, Takanohana began answering questions in more detail after his 1994 promotion to yokozuna, but reporters were taken by surprise at the July 1998 tournament when he suddenly became much more talkative. Apparently, his physical trainer had suggested that it would be better if he spoke more frankly, and he would sometimes bring up topics other than sumō and spend a long time chatting with reporters.

Asked what he did to relax in his rank as yokozuna, Takanohana answered “Talking with all of you here,” with a smile on his face. This newly talkative Takanohana surprised many reporters, but he fell silent again following reports of a rift with his brother just before the next tournament in September that year.

Reporters covering the dressing rooms interview several rikishi at a time and jot down their ring name or nickname to keep track of who was interviewed. For example, a reporter’s notes may be prefaced by the name Asashōryū or Dorge, Asashōryū’s Mongolian name, followed by the pertinent comment. But one day, a certain reporter, who may have been in a hurry, wrote “Do-ru,” [from the Japanese pronunciation of Dorge, Do-ru-je].

Sharp-eyed Asashōryū, after answering a number of questions, addressed the reporter, saying “You’re writing everything down properly, aren’t you?” Glancing at the reporter’s notebook, he spotted “Doru” and jokingly asked, “What’s up with this ‘Doru?’ My name has three syllables, Do-ru-je, you know. Why is the third syllable missing? Don’t mix me up with any doru [dollar],” and playfully knuckle-rapped the man’s head.

This episode is a good example of quick-witted Asashōryū’s repartee. But he had emotional ups and downs: When he was in a good mood, he was capable of perceptive comments, but he would turn overbearing and unapproachable whenever news of his bad behavior became public.

Asashōryū in a jovial mood at the 2003 September basho, after winning his fourth grand tournament championship. (© Kyōdō)

Mixed Zone Introduced During the Pandemic

Among all the world’s sports, Sumō must be among those with the freest environment for mingling between competitors and the press, even before bouts. But the COVID-19 pandemic upended this longstanding tradition.

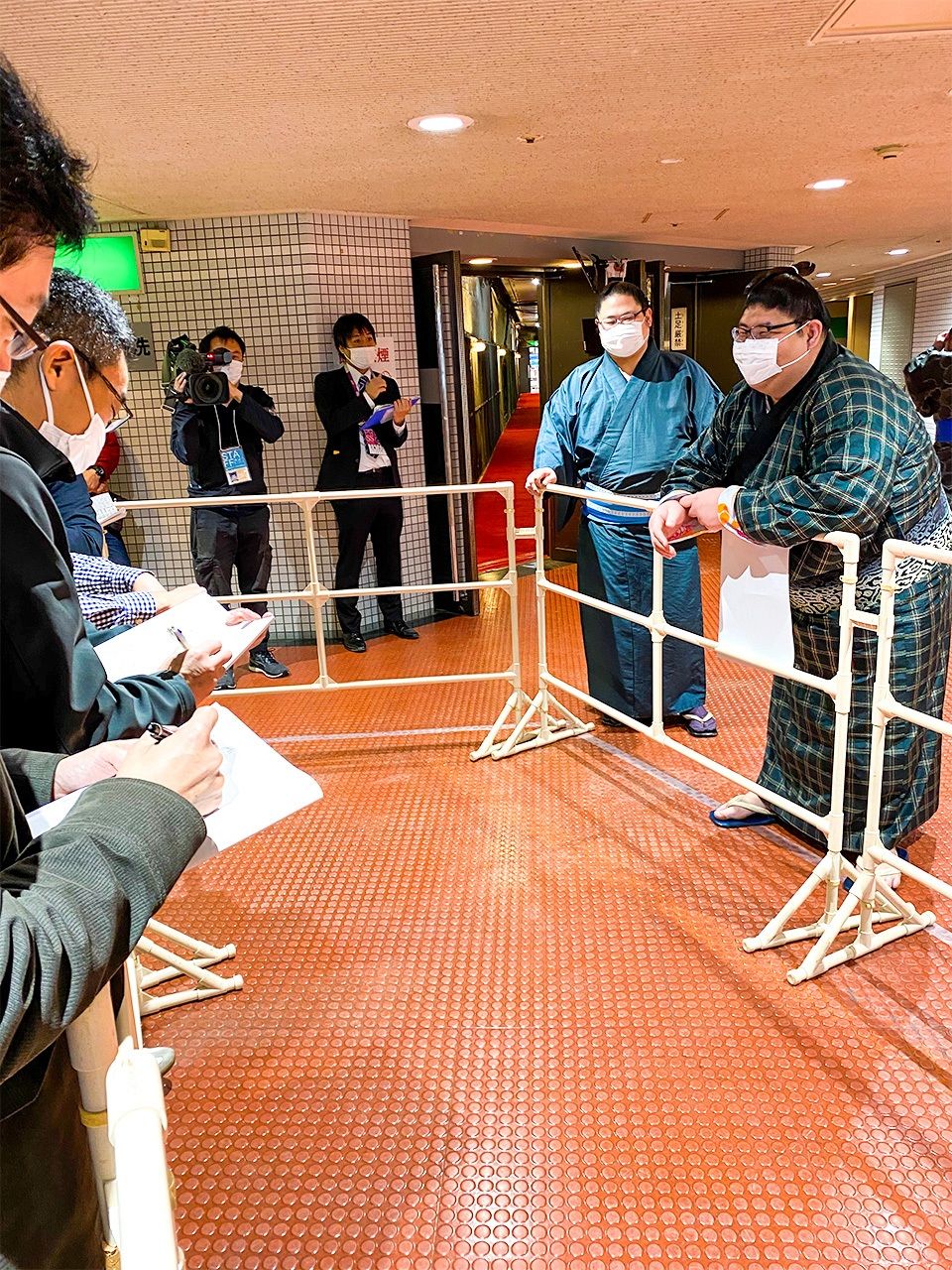

The March 2020 tournament was the first ever held behind closed doors. Reporters were not allowed to mingle with rikishi, and none could enter the shitaku beya for interviews. But to allow for some press coverage, a “mixed zone” with a 2-meter-wide corridor was set up outside each dressing room. Reporters standing to one side could hold brief postmatch interviews with rikishi filing past on the other, but some simply kept walking and ignored reporters. Even so, the mixed zone arrangement did give the media brief opportunities to hear directly from the fighters.

Reporting from the mixed zone at the March 2020 tournament. (© Nagayama Satoshi)

The May 2020 tournament was cancelled outright, as the government had put a state of emergency into effect, only the third time in sumō history that a tournament had been called off. In July, the tournament usually held in Nagoya took place in Tokyo at the Ryōgoku Kokugikan before a limited number of spectators. Interviews with rikishi were conducted online only, a practice that continued even after regional tournaments resumed.

It was only with the May 2023 tournament, following the May 8 official downgrading of COVID-19 to the level of a seasonal ailment, that the media were once again allowed into the shitaku beya, but only to interview yokozuna and ōzeki, and only with the individuals’ permission. Takakeishō, in danger of being demoted from ōzeki rank, refused to be interviewed at any time during the tournament.

Rikishi in the lower ranks of the top echelon were allowed to meet the press in a mixed zone set up at the Sumō Training Center next to the main hall. Here, reporters could get up closer to the wrestlers, although the two sides were still kept 1-and-a-half meters apart. Again, quite a few rikishi ignored the press and sailed through the zone without stopping.

At the 2023 May tournament, a mixed zone was set up for the first time for a tournament taking place in Tokyo. Asanoyama, marking a win on the first day after returning to the top ranks, speaks with the media. (© Nagayama Satoshi)

I hope media coverage will soon return to normal, with the press once again being allowed into the shitaku beya. Coverage was done remotely for the past three years, leading to a marked dearth of notable comments or memorable conversations. As the episode with Kotoōshū shows, even if a rikishi says nothing, being able to mingle with the wrestlers, something no other sport offers, gives sports journalists an invaluable opportunity to gain insight into the competitors’ thoughts, both before and after their bouts.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 20, 2023. Banner photo: Yokozuna Takanohana chatting with the media. While making his way up the ranks, he spoke little but after promotion to the top spot, he mellowed considerably and gradually began opening up. Photo courtesy of Amano Hisaki.)