Japan’s Loan-Based Scholarship System Leaves Students Saddled with Debt

Economy Education Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Little Prospect for Repayment

Scholarships were initially intended to help underprivileged students attain higher education. However, factors like rising tuitions and growing economic pressure on households have made it so that now around half of Japanese university students rely on scholarships to pay for school. A sizable number of these are loan-based public scholarships offered by the government-run Japan Student Services Organization, or JASSO, resulting in many students leaving school heavily in debt.

As student debt has risen, Japan’s labor market has seen stagnant wage growth and a significant increase in nonregular employment. These and other factors have produced an uptick in the number of borrowers who are unable to pay back their student loans. I spoke with one woman who received a ¥2.5 million loan-based scholarship from JASSO but had to drop out of university in her second year after her father pilfered her money for his business.

Despite withdrawing from school, she had to begin repaying her loans the same as if she had graduated. But having failed to attain a degree, she had limited employment options. She took a job in the basement food market of a department store, but the meager income she earned was not enough to cover her monthly loan payments of ¥15,000. Fortunately, she was given a temporary reprieve through a measure allowing borrowers who are having financial difficulties to defer repayment for up to 10 years.

Nine years on, though, this woman, now in her thirties, has seen little improvement in her economic situation. She has worked at a call center for the last seven years, but as a nonregular employee she is excluded from seasonal bonuses, and she says she previously received only nominal hourly wage increases of ¥10 or ¥20 twice a year—hardly enough to keep up with the rising cost of living. Working four days a week, her take-home pay hovers around ¥180,000 a month.

Complicating her financial situation further, she was hospitalized for a time and had to borrow money from a consumer loan company at high interest to make ends meet, putting her deeper in debt. With only one year to go before her student loan payments resume, she faces the real risk of falling into delinquency.

Demonstrators in Tokyo call for raising the average hourly minimum wage to ¥1,500. It currently exceeds ¥1,000 in only eight prefectures. (© Jiji)

This year’s shuntō spring wage negotiations by labor unions offered a small ray of hope by pushing real wages upward in most industries. The woman in question saw her hourly wage jump by ¥300, lifting her monthly income over ¥200,000. She says that the amount makes “all the difference in the world” as she is now eligible to reduce her student loan repayments by half to ¥7,500 when her deferment period ends.

While this provides a modicum of relief in the short term, it nearly doubles the length of her loan from 19 to 34 years, meaning she will be in her sixties before she pays the last of the some ¥2 million that she still owes. This is assuming that she remains in the workforce. Given her health issues, she says that the uncertainty of her situation weighs heavily on her mind. The prospect of being unable to work haunts her. “I’ll almost certainly become delinquent and then have to declare bankruptcy,” she says. Even with her recent pay raise, she remains pessimistic about the future. “Everything is up in the air.”

She holds up her experience as a critique of Japan’s loan-based scholarships, asserting that “compared to how easy it is to receive scholarships, the conditions for repayment are quite strict. I was a naïve high school student when I applied for my student loans, and I’ve learned the hard way just how treacherous it is to take on such ”

Income Woes

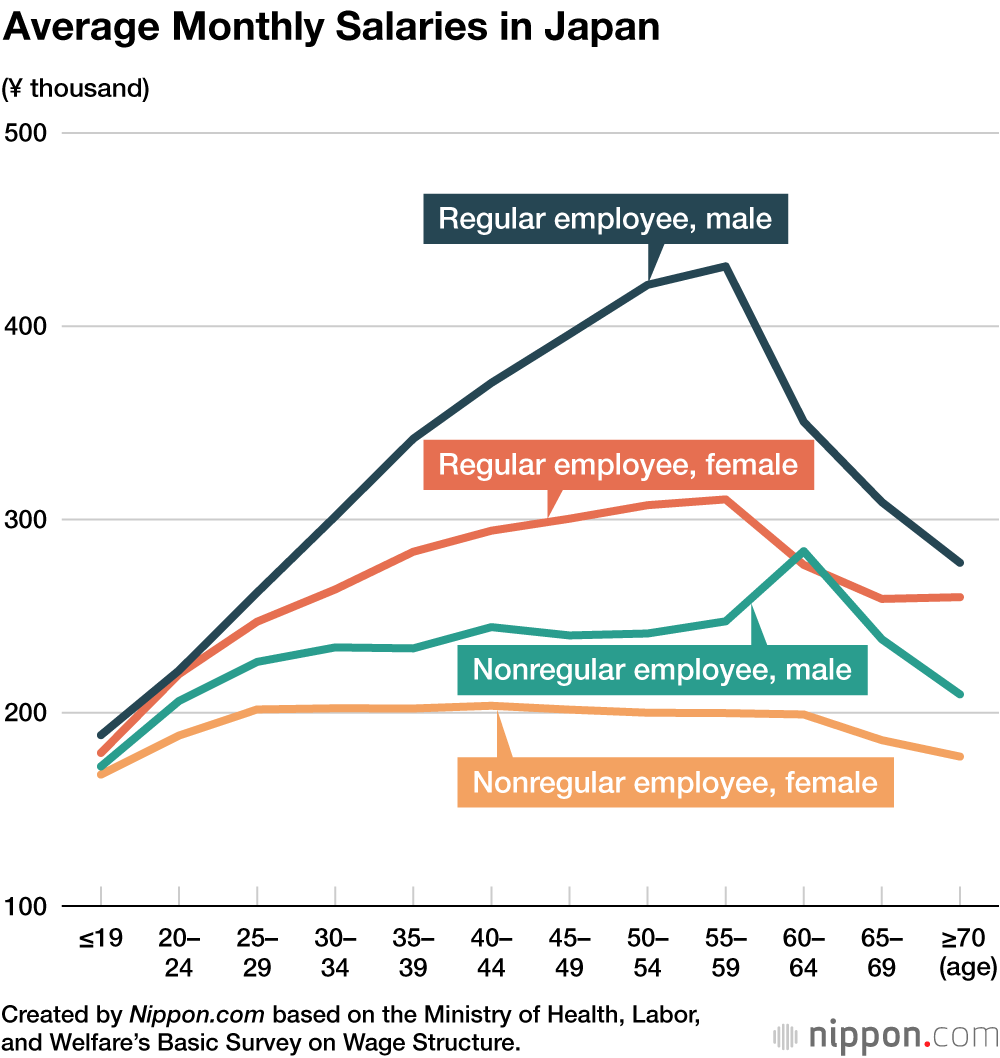

In taking on debt, young borrowers risk becoming stuck in low-paying, nonregular positions. Nonregular workers, who account for 40% of the labor force, are typically paid lower wages than regular, full-time employees and are more likely to see their incomes stagnate, resulting in a widening wage gap. The impact on women is two-fold due to Japan’s persistent gender pay gap.

Circumstances are hardly better for many regular employees who do not enjoy stable, high-paying positions at major corporations. Ōuchi Hirokazu, a sociology of education professor at Musashi University, points to the growing hordes of company employees whose compensation and benefit packages are substandard, what he calls “regular workers in name alone.” He says that even if employees are just eking by on their monthly paychecks, they should be able to repay their school loans if their company provides adequate bonuses. However, a growing number of regular employees, particularly those in IT, distribution, tutoring, and the service sector, only earn around ¥4 million a year (about ¥3.2 million in take-home pay after taxes and social insurance deductions) and receive bonuses equivalent to less than a month’s salary. Ōuchi points out that “such individuals living in major cities will find it hard to get by.”

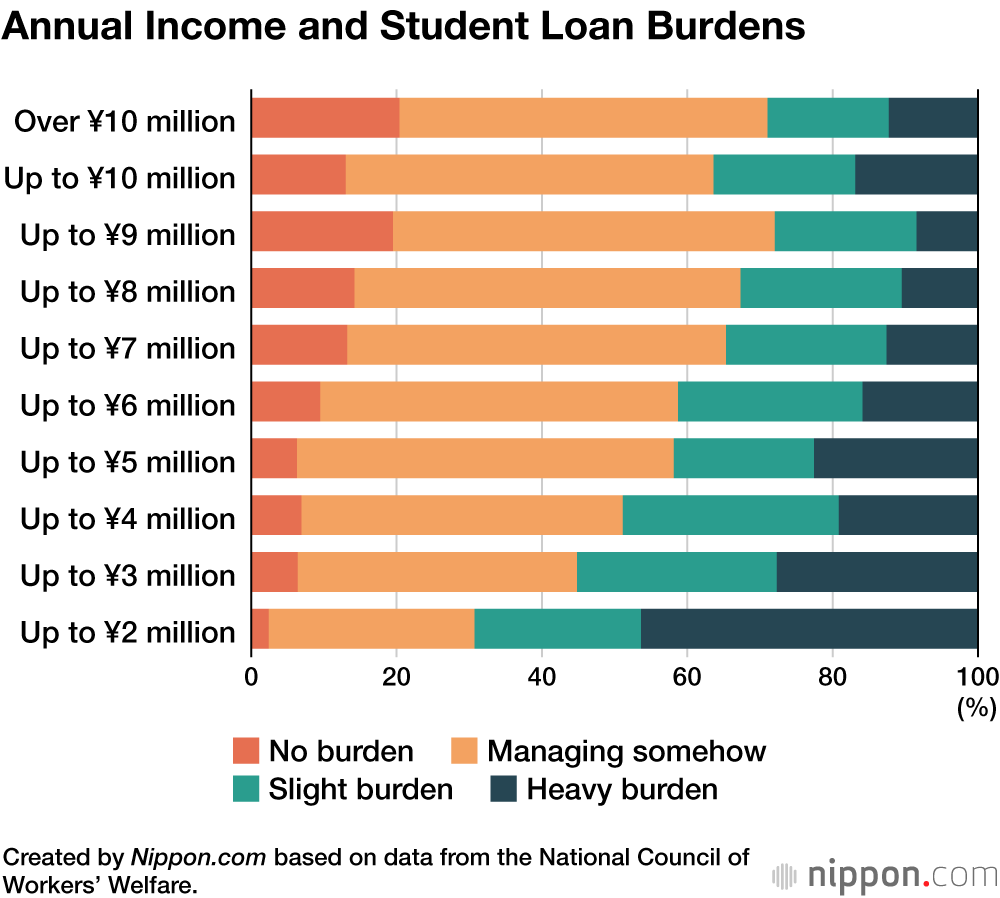

Ōuchi notes that while borrowers who have an annual income of less than ¥3 million are able to defer repayment of their JASSO loans for up to 10 years, no relief measures exist for people earning even one yen over this. “People whose salaries put them just north of the line—those earning between three million and four million yen a year—are the most hard pressed to pay back their loans.”

Iwamoto Nana of the labor NPO Posse says that low-wage earners are often at the mercy of so-called black companies, businesses that employ abusive and exploitative practices. “Many of the individuals who come to us have quit their jobs for mental health reasons after being made to work unreasonably long hours or having other excessive burdens placed on them,” she explains.

She describes a worrying trend among companies of hiring a slew of new university graduates with the intent of squeezing as much work out of them as possible. Worked into the ground, regular employees who have quit for health reasons typically find their employment options reduced and often have to settle for nonregular positions at exploitive companies when they reenter the workforce.

Delinquent Loans

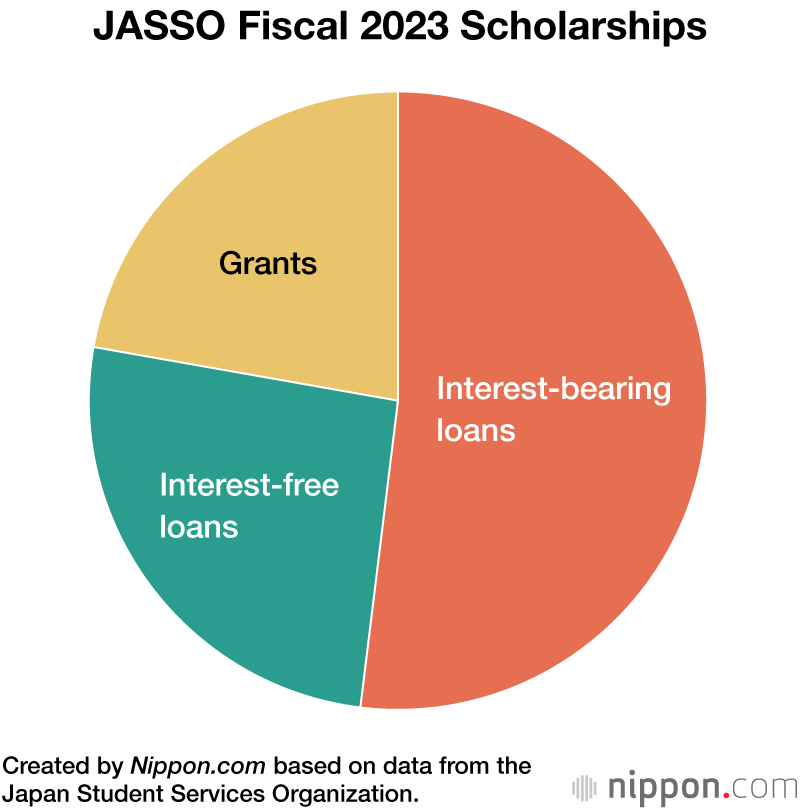

According to a 2020 student survey by JASSO, 49.6% of university students receive loan-based scholarships. JASSO itself provides 33% of the total for all types of scholarships for higher education, with 80% of these being either interest-bearing or interest-free loans requiring repayment. A mere 20% of the financial aid it offers are grants.

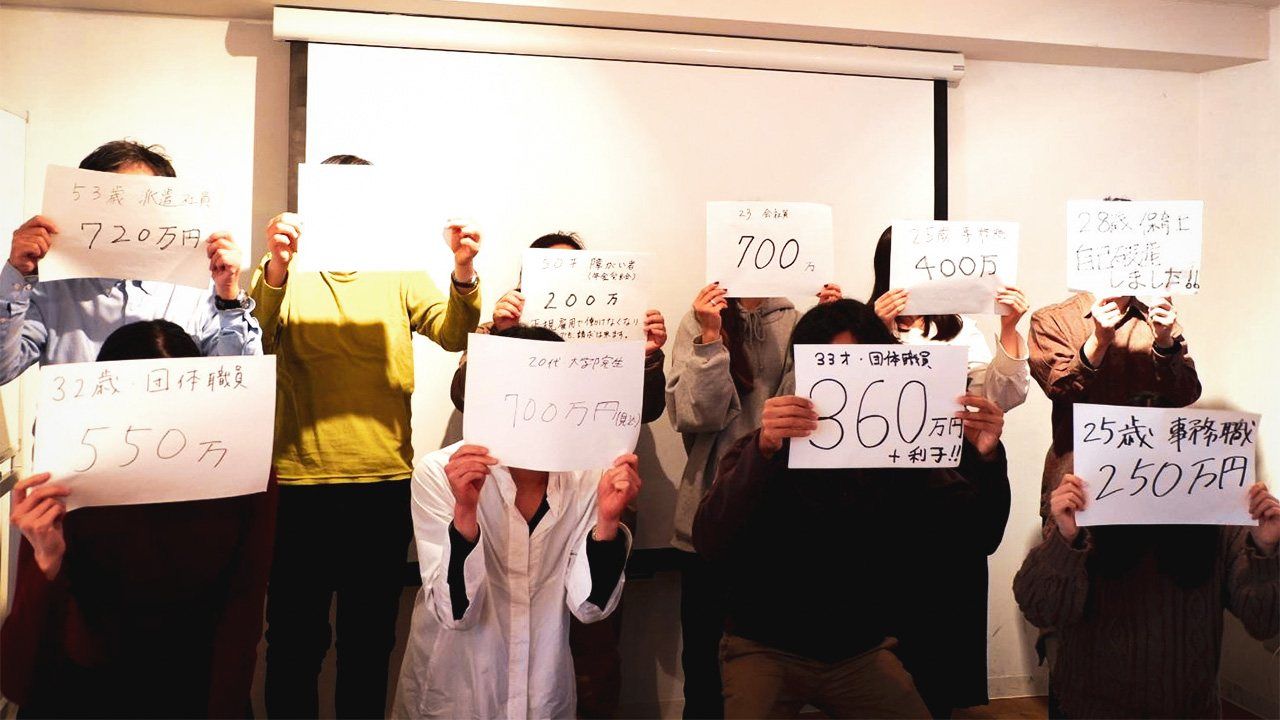

A survey of 2,200 individuals by the National Council of Workers’ Welfare found that on average, students take out ¥3.1 million in education loans, and that among borrowers, 26.9% have been delinquent at some point. A separate survey of 3,100 students by Posse found that 10% of borrowers have considered declaring personal bankruptcy. Notable among this group were individuals who had borrowed large sums, in some cases as much ¥8 million for art college students or ¥10 million for students in science and technology majors.

Iwashige Yoshiharu, a lawyer who deals with student loan issues, advises that borrowers at risk of delinquency know what options are available to them, including personal bankruptcy. “JASSO’s relief measures are extremely inadequate,” he says. “Bankruptcy is a very powerful tool for someone who is in debt.” Iwashige recommends that people struggling to pay back loans learn about the procedure and consider it as an option.

Limited Options in Life

Posse’s Iwamoto points out how the situation for female borrowers is particularly precarious. She notes that women who rely on their husbands to pay back their student loans all too frequently become targets of domestic abuse and suffer strained relations with their in-laws.

The woman interviewed above says that for her part, she is determined to solve her student loan debt on her own, even if it means putting off finding a romantic partner. “I’m not interested in finding some rich guy to bail me out of my predicament,” she declares. “I’ll start thinking about looking for a life partner once I get my finances straightened out.”

Growing up in a poor household, she says there was no money for lessons outside of school, which along with her own financial struggles has dampened her desire to have children of her own. “I don’t want them to go through what I have,” she says. “It would be unfair to bring a child into the world only for it to suffer.”

Faced with student loan debt, she has been forced to put marriage on hold and decided to give motherhood a pass.

Demographic Considerations

According to an NCWW survey on the effects of student debt on life decisions, 37.5% of respondents cited marriage, 31.1% giving birth, and 31.8% childrearing as being impacted by their financial situations. A further 65.6% expressed unease about their ability to save money for the future.

These figures bode poorly for Japan’s efforts to boost its falling birthrate. Ōuchi says the government could alleviate some of the downward pressure by bolstering student debt relief. “Getting married and starting a family is of course a personal decision,” he explains. “But the authorities still need to quickly enact measures to address the falling birthrate by reducing the burden of having children. The population may not increase, but at the very least, it needs to be kept at a level that can sustain society.”

Student debt weighs most heavily on members of the younger generations, those in their twenties to forties, limiting their options for marriage and family. “Reducing the number of individuals struggling under mountains of debt will improve the situation immensely,” Ōuchi stresses. He proposes expanding grants and student debt relief, such as is being considered in the United States. “Reduce the repayment burden of student loans could be achieved quickly and would be very effective.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Attendees at a seminar on scholarships hosted by the NPO Posse hold up pieces of paper showing their student loan amounts. © Posse.)

university students Nonregular employees finance salary scholarship bankruptcy