By the People’s Side: Imperial Family Visits to Disaster Areas

Imperial Family Disaster Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Popular “Heisei Style”

On February 23, Emperor Naruhito made special mention of the devastating New Year’s Day Noto Peninsula earthquake during his annual birthday press conference. He told reporters in attendance that he was deeply saddened that so many people had lost their lives and expressed concern that others have been forced to evacuate or were still missing. He also expressed his desire to visit the afflicted regions at the earliest possible opportunity.

This would follow in the footsteps of the Heisei emperor and empress (now styled the Emperor Emeritus Akihito and Empress Emerita Michiko), who reigned from 1989 until his abdication in 2019 that ushered in the Reiwa era. Following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko notably made visits to meet the victims of the disaster in seven consecutive weeks. They visited the greatly affected Tōhoku prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima a total of 13 times before the 2019 abdication.

Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako visited the same three prefectures nine times as crown prince and crown princess, and a further five times after their tenure began in 2019, including “virtual visits” during the COVID-19 epidemic where they interacted with residents online in disaster areas. The current emperor and empress therefore have inherited their predecessors’ tradition of providing consolation to victims in regions afflicted by Japan’s many natural disasters as they fulfil the emperor’s role as the symbol of the “unity of the people.”

Crown Prince Naruhito and Crown Princess Masako talk to victims at an evacuation center following the Great East Japan Earthquake. Photograph taken in June 2011, Yamamoto, Miyagi Prefecture. (© Jiji)

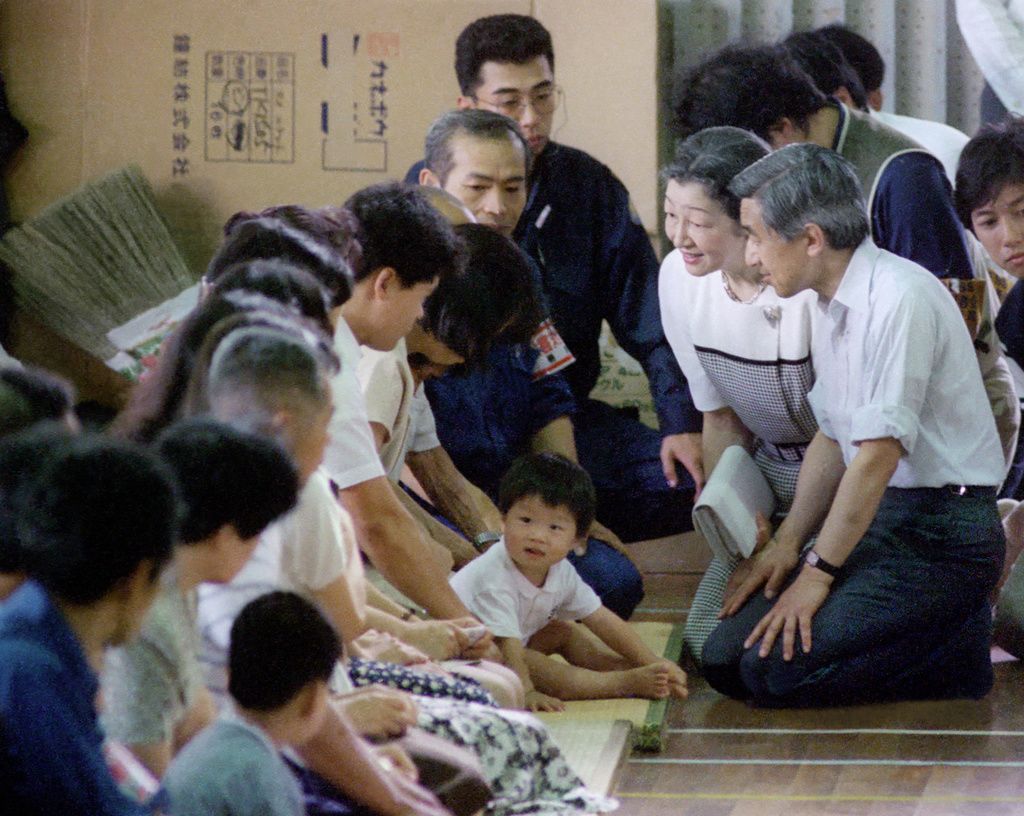

While taking care not to burden local officials and residents working toward recovery, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko proactively visited disaster-stricken areas as soon as they could during their tenure. When visiting evacuation shelters, they would often be seen exchanging words with victims while sitting in seiza, a position where they kneel while sitting on their ankles and heels. Such a scene could scarcely be imagined during the Shōwa era (1926–89), leading to this method of providing consolation while talking face-to-face with victims becoming known as the “Heisei style.”

Kanegae Kan’ichi, mayor of Shimabara, Nagasaki Prefecture, explains the situation to Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko during their July 10, 1991, visit to the city after the June 3 eruption of Mount Unzen’s peak of Fugen-dake, in which. 43 people died from pyroclastic flows. (Courtesy Kanegae Kan’ichi; © Jiji)

Emperor Akihito’s first official visit to a disaster area took place in July 1991, three years after his ascension to the throne. Travelling to Shimabara in Nagasaki Prefecture with Empress Michiko after the eruption of Mount Unzen, he was seen listening carefully to explanations from the mayor of Shimabara with his shirt sleeves rolled up. The Emperor and Empress also knelt in the seiza position to talk to residents who had been evacuated to an emergency shelter.

Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko sit while talking to evacuated residents in Shimabara, Nagasaki, following the eruption of Mount Unzen. Taken July 10, 1991. (© Kyōdō)

The emperor of Japan taking this position was actually met with objections at the time. A person close to the imperial family recalls hearing that people complained to the Imperial Household Agency and were upset that they had “made the emperor kneel down.”

The emperor and empress, however, continued with this “Heisei style.” The person also noted that, “standing up, you cannot hear the voices of people sitting on the floor—people who are exhausted due to having been forced to evacuate following a disaster. Their Majesties were motivated by a sincere desire to listen to the stories of victims in the shelter and felt that kneeling was therefore an entirely natural action.”

The emperor and empress talking to people in the Miyako Public Sports Hall shelter after the Great East Japan Earthquake on May 6, 2011, Miyako, Iwate Prefecture. (© Jiji)

Following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko continued to express their solidarity with victims through numerous visits to tsunami-affected areas. On one occasion in July 2013, they visited Tōno in Iwate Prefecture, a municipality that played a key role in providing logistical support to coastal areas during the disaster’s response and recovery stage. During the visit, they were briefed by Maekawa Saori of the Tōno Cultural Affairs Section on the activities of the Cultural Heritage Rescue Program, which restores tsunami-damaged heritage and coordinates the donation of books to affected sites. It turned out that Prince Akishino (Emperor Naruhito’s brother and the current crown prince) had attended a CHRP event in Tokyo before and had related its activities to the emperor. Empress Michiko also showed great empathy by remarking to Maekawa on how time-consuming and complicated book donation activities were. From these interactions, Maekawa felt uplifted, knowing that the imperial family was paying attention to her organization’s efforts from afar.

The current emperor and empress have continued this tradition of face-to-face meetings. In June 2023, for the first time since accession to the throne, they visited a disaster-affected area in person to attend a national tree-planting ceremony in Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture. At the Tsunami Memorial Museum of the Great East Japan Earthquake, Emperor Naruhito said to guide Hitokabe Masuyo, “Your father was a fisherman, wasn’t he? He must have gone through a very hard time.” Hitokabe had simply mentioned in the information that he sent to the prefectural government before the visit that his father’s boat and fishing equipment had been damaged by the tsunami. The emperor’s comment showed that he had paid careful attention to this information and, as Hitokabe recalls, that “just by mentioning what my father did, I felt that he empathized with all that I had been holding in my heart up until then.”

Avoiding Telling People to “Keep at It”

“It’s tough, isn’t it?” “How has it been for you?” “Take care of yourself.”

Many people heard these words from Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko during their visits to evacuation shelters following a natural disaster. While they carefully listened to the stories of the victims, they kept their own comments brief. However, the imperial couple were very careful never to say ganbatte kudasai, the phrase meaning “keep at it” or “do your best.” Haketa Shingo, grand steward of the Imperial Household Agency at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake, reflects on their choice of words:

Rather than visiting to these areas to explicitly “encourage” the victims of natural disasters, Their Majesties visited out of courtesy and to offer empathy to those in distress. Rather than being told to “keep at it,” the victims would feel more supported and have courage instilled in them through such empathy. Gloomy expressions were often transformed into optimism by these visits through the opportunity to tell their stories to Their Majesties.

Kawashima Yutaka, Emperor Akihito’s chief chamberlain from 2007 to 2015, writes in his memoirs:

I believe that Their Majesties, despite the calmness with which they spoke to the victims, were deeply affected by the suffering they witnessed, and will carry it with them for the rest of their lives. At the same time, I think they were intentionally reserved and careful. They did not want to give the impression that, as people who had not lived through the disaster, they truly understood the pain and grief of those affected. Their Majesties’ task is a very hard one that is impossible to truly get used to, but they still go to the locations and perform the task of consoling the people.

As Kawashima notes, the feelings of the emperor and empress are not momentary, and they continue remembrance even today. In 2005, at the tenth anniversary of the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, a representative of the victims’ families presented them with seeds from sunflowers that neighbors had planted on the site of the former home of Katō Haruka, a 12-year-old girl who had died in the disaster. They then planted them in the garden of their residence and tended to them year after year. Emperor Akihito composed a poem about these sunflowers at the last poetry reading of his tenure:

These sunflowers grown

From seeds presented to us

How tall they now are

Their leaves spreading out widely

In the early summer light.

Now, as emperor emeritus and empress emerita, they continue to tend to these sunflowers and keep them in bloom at their new residence (the Sentō Imperial Palace).

Embodying Their Constitutional Role

Emperor Akihito made many visits to disaster areas despite intermittent difficulties with his health. For example, in the autumn of 2011—less than half a year after the Great East Japan Earthquake—he was admitted to the hospital for pneumonia, and in the following year he underwent bypass heart surgery. Although Haketa and others advised him to reduce his duties, he continued to visit disaster areas. In the speech he gave in August 2016 to communicate his intention to abdicate, he stated:

I have considered that the first and foremost duty of the Emperor is to pray for peace and happiness of all the people. At the same time, I also believe that in some cases it is essential to stand by the people, listen to their voices, and be close to them in their thoughts. In order to carry out the duties of the Emperor as the symbol of the State and as a symbol of the unity of the people, the Emperor needs to seek from the people their understanding on the role of the symbol of the State. I think that likewise, there is need for the Emperor to have a deep awareness of his own role as the Emperor, deep understanding of the people, and willingness to nurture within himself the awareness of being with the people. In this regard, I have felt that my travels to various places throughout Japan, in particular, to remote places and islands, are important acts of the Emperor as the symbol of the State and I have carried them out in that spirit.

Emperor Akihito continually sought to embody the “symbol of the State and of the unity of the People” as defined in Japan’s postwar constitution. In the process, he and his wife won the trust and empathy of the majority of Japanese citizens. Haketa believes that such visits to affected areas were the result of deep and careful reflection on how to embody the emperor’s constitutional role as the symbol of the Japanese nation and the people’s unity.

Haketa Shingo during an interview on February 22, 2024, in Minato, Tokyo. (© Nippon.com)

Inheriting the “Heisei Style”

Emperor Naruhito is Japan’s first monarch to be born after World War II. Throughout his life he has been conscious of not only inheriting the throne but also of the evolving, symbolic role of the emperor of Japan and how it has transformed in line with changes in Japanese society. In February 2018, not long before ascending to the throne, the then crown prince told participants at a press conference that he too would emulate his father in devoting his body and soul to sincerely performing the official duties of the emperor as a symbol of national unity.

During the 2023 visit to Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture, he attended a musical performance on a viola made from a part of the Miracle Pine, a tree that withstood the tsunami and became a symbol of postdisaster reconstruction. This was the same viola that he himself had played at a concert in July 2013.

Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako observe the “Miracle Pine” at the Takatamatsubara Memorial Park for Tsunami Disaster, Rikuzentakata, Iwate Prefecture, on June 3, 2023. (© Jiji)

Stringed-instrument maker Nakazawa Muneyuki has crafted 11 instruments—including violins, violas, and cellos—from wood of dead pine trees taken from the rubble of Rikuzentakata. When Empress Michiko attended a violin concert for tsunami recovery in January 2013, Nakazawa said that he wanted the crown prince (the current emperor) to play one of these instruments. This wish was fulfilled at a concert in July, the same year when Crown Prince Naruhito performed with a viola from this series with the Gakushūin University Alumni Orchestra.

Crown Prince Naruhito performs on a viola with the “Miracle Pine” painted on its back at a July 2013 Gakushūin University Alumni Orchestra concert in Toshima, Tokyo. (© Jiji)

To preserve the memory of the disaster, Nakazawa has been working on a project to bring together 1,000 professional and amateur musicians to play violins and other instruments made from tsunami debris. Empress Emerita Michiko has told him of her belief that music has the power to reach people and move their hearts and that this work needed to continue after they were gone. Her words align perfectly with the image of Japan’s emperor committed to being in constant contact with citizens, and Nakazawa admits that tears come to his eyes at the memory of that moment.

Nakazawa Muneyuki, a stringed-instrument maker, holding the Tsunami viola played by Emperor Naruhito (then crown prince). Taken on February 19, 2024, in Shibuya, Tokyo. (© Nippon.com)

Rikuzentakata Mayor Sasaki Taku recalls the imperial couple’s visit to his town in 2023: “It was as if time was moving slowly, creating a serene atmosphere that allowed the victims to express what they had been holding inside them. It created a special place for them.” Haketa, who witnessed such scenes countless times, explains emotionally that this “is the essence of the emperor as a symbol of the nation. No politician or official can do that.”

Even as Emperor Naruhito and Empress Masako fashion a fresh image of the symbol of Japanese national unity for a new era, it is certain that they will continue the empathetic tradition of providing consolation to the victims of natural disasters.

(Originally published in Japanese on March 11, 2024. Banner photo: Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko visit Utatsu in Minamisanriku, Miyagi Prefecture, on April 27, 2011, to meet with victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake. They bow silently facing the tsunami-devastated area from the raised ground of a primary school. © Jiji.)