The Frozen North: Negotiations on the Northern Territories at a Standstill

Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Anguish of an Aging Population

The Shiretoko Peninsula, a registered UNESCO World Heritage Site, juts out from northeastern Hokkaidō and is dotted with numerous volcanic peaks. Sitting at the foot of the Shiretoko mountain range is the town of Rausu. A resident here, Waki Kimio (83), is a native of Kunashiri, one of the islands that make up the Northern Territories that are claimed by Japan but controlled by Russia. Waki tells us how his hope to return home to the island Russia now calls Kunashir has faded in recent years: “Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there has been absolutely no progress on negotiations to reclaim the Northern Territories. I no longer feel like I can see the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Waki is the former president of the Chishima Renmei (League of Residents of Chishima and Habomai Islands), an organization of former residents of the Northern Territories. On February 7—Japan’s officially designated “Northern Territories Day”—Waki joined 750 other participants at an annual meeting in Hokkaidō’s Nemuro to demand the return of the islands.

The February 2024 Nemuro convention demanding the return of the Northern Territories. (Courtesy of Nemuro City Council).

February 7 was chosen for Northern Territories Day because that was the date the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between Japan and Russia was signed in Shimoda, Shizuoka Prefecture, in 1855. The Shimoda Treaty delimited the border between Japan and Russia within the Kurils, drawing the boundary between Etorofu (administered by Russia as Iturup) and Urup, with the status of left undetermined. This essentially established the Northern Territories as consisting of the four islands of Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan, and Habomai (which is actually a collection of smaller islands) that stretch out from northeast Hokkaidō towards the Kamchatka Peninsula.

According to Nemuro officials, turnout for this years’ Northern Territories Day event was down by 100 people from last year. The stalled dialogue between Japan and Russia provided a further reason for the solemn faces of people at the meeting.

In Tokyo, Prime Minister Kishida Fumio also spoke at a convention on February 7 demanding the return of the Northern Territories. While the prime minister reiterated the government’s determination to resolve the territorial issue by working towards a formal peace treaty, he limited himself to facilitating the resumption of exchanges between the islanders and visits to grave sites within the Northern Territories in terms of concrete measures on the government’s immediate agenda.

The official Japanese government position is that the islands of the Northern Territories “are an inherent territory of Japan, which have never been held by foreign countries.” According to Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Northern Territories were illegally occupied by the Soviet Union (and now Russia) “after Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration and made it clear its intent to surrender,” and in violation of the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact that was still in force in August 1945. As Japan’s surrender was being accepted, the Soviet Union “continued its offensive against Japan and occupied all of the Four Northern Islands from 28 August 1945 to 5 September 1945.”

Russia’s Anger at Sanctions

Even after Russia annexed Crimea in southern Ukraine in 2014, the administration of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō quickly resumed dialogue with Russia, thereby prioritizing negotiations over the Northern Territories and a peace treaty. At the time, this stance was met with opposition from the United States and European nations. It was a different story following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, however, as Prime Minister Kishida and the Japanese government decisively aligned with Western counterparts to impose economic sanctions.

On diplomacy with Russia, ahead of the G7 summit in Hiroshima in May 2023 Prime Minister Kishida outlined his stance in an essay contributed to the journal Gaikō (Diplomacy) in March that year: “I felt a strong sense of crisis that ‘Ukraine may be the East Asia of tomorrow.’ That is why last year, I . . . made the decision to respond firmly to the aggression by imposing strict sanctions against Russia and providing strong support for Ukraine.” The background to this are worries in Japan that if Russia’s actions are left unchecked in Europe, then the activities of China and North Korea will gain momentum in East Asia.

In March 2022, immediately following Japan’s announcement that it would join the sanctions against Russia, Moscow ceased negotiations for a peace treaty, including the territorial dispute; this also put an end to the program of visa-free travel to the islands for Japanese visitors and to Japan for Russian inhabitants of the islands that had been in place since 1992. With the situation in Ukraine in a stalemate, and with no official dialogue between the Japanese and Russian governments taking place, short-term hopes for a peace treaty and resolution of territorial issues have been dashed.

The Fallout from Previous Diplomatic Efforts

The former residents of the Northern Territories have shown understanding for Japan’s application of sanctions against Russia. However, they have expressed disappointment with the large enthusiasm gap between Japan’s current leadership and that of Abe Shinzō’s 2012–20 administration, which pursued forward-looking diplomacy with Russia, including repeated summit meetings with President Vladimir Putin.

Prime Minister Abe (left) shakes hands with President Vladimir Putin on June 29, 2019, in Osaka. (© Jiji Press)

In May 2016, Abe and Putin agreed to pursue a “new approach” to resolving the Northern Territories’ issue and the conclusion of a peace treaty at a summit meeting in Sochi, Russia. Then, in November 2018 in Singapore, the two leaders agreed to accelerate negotiations based on the 1956 Japan-Soviet Joint Declaration. The Joint Declaration was signed in place of a peace treaty and terminated the state of war between both countries, normalizing diplomatic relations. The Joint Declaration also committed both sides to continue negotiations towards a peace treaty based on the expectation that the Soviet Union would eventually hand over Habomai and Shikotan to Japan.

According to Abe Shinzō’s memoirs, in September 2018 President Putin suggested ahead of the Singapore meeting that Tokyo and Moscow work toward concluding a peace treaty by the end of the year, “without preconditions.” Abe decided to “go all in” by committing himself to a return to the formula of the Joint Declaration, if necessary, to secure Moscow’s agreement to a peace treaty. His strategy was to leverage his personal relationship with Putin to promote joint economic activities with Russia while seeking to revitalize negotiations on the Northern Territories. In the memoirs, Abe also notes, “if we are serious about realizing the return of the Northern Territories, we must first present a proposal that stimulates the interest of the other side as well.”

While the former residents expressed concern about the collapse of the “four islands” reversion framework, they were encouraged by the “two islands” approach and the seeming progress on negotiations. Based on several discussions with the former prime minister, Waki recalls that “Abe’s resolve toward dealing with the Northern Territories was quite strong.”

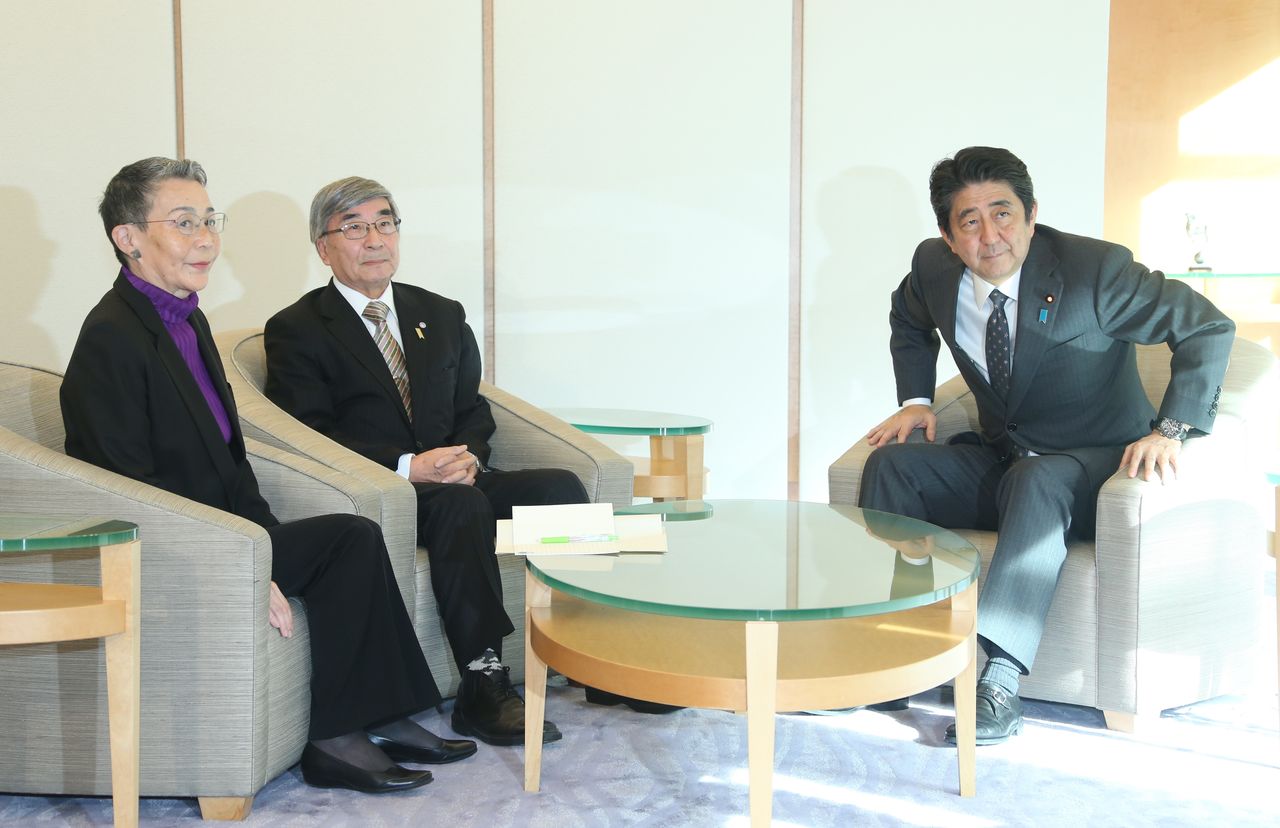

Prime Minister Abe talks with former residents of the Northern Territories at the Prime Minister’s Office in Tokyo, December 2016. Waki Kimio is second from left. (© Jiji)

It is the case, however, that negotiations with Moscow had already stalled even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In December 2018, President Putin suggested concern over the possibility of the United States—as Japan’s ally—deploying its military to the Northern Territories should Russia return the islands. The Russian side then insisted that progress would be based on the precondition of Japan recognizing that the Northern Territories were legitimately acquired by Russia as a result of the outcome of World War II. Then, in July 2020, Russia’s constitution was amended to specifically prohibit the ceding of territory. Thus, even before the Ukraine invasion, critics had labelled the Abe administration’s diplomacy toward Russia a “failure” that had only resulted in Japan alone making concessions and without any concrete achievements. In light of these developments and critiques, Abe’s successors as prime minister—Suga Yoshihide and Kishida Fumio—have avoided taking a proactive stance on negotiations with Russia on these issues.

Entry Bans, Lighthouse Flags, and Other Provocations

Russia continued its provocative actions regarding the Northern Territories following its invasion of Ukraine. In May 2022, the Russian government announced an entry ban on Prime Minister Kishida and other government officials, as well as on Japanese activists involved in the campaign to have the islands returned. In April 2023, Moscow designated the Chishima Renmei organization for former residents an “undesirable organization,” banning its activities in Russia.

Then in the summer of 2023, the Russian government reemphasized its “effective control” of the islands by raising the national flag at a lighthouse on Kaigara Island. Only 3.7 kilometers from Cape Nosappu on the easternmost tip of the Nemuro Peninsula, the Japanese-built lighthouse is visible to the naked eye. Russia also repainted the wall surface of the lighthouse in different colors and installed the cross of the Russian Orthodox Church to emphasize its control.

Lighthouse on Kaigara Island displaying the Russian flag in July 2023. The walls were painted white and a Russian Orthodox cross and other symbols were displayed as a show of control. (Left photo © Itazawa Naoki, a third-generation former resident of Kunashiri living in Nemuro; right photo courtesy of another Nemuro resident)

The Russian side also suspended portions of intergovernmental agreements from the 1990s that allowed for visa-free visits by former residents to the islands. By labelling Chishima Renmei an “undesirable organization,” the Russian government also effectively raised the hurdles for people hoping to tend family graves on the islands, despite nominally allowing such visits as part of humanitarian measures still in place. Many islanders have paid their respects to the graves from sea, clasping their hands in prayer from the decks of boats offshore.

Finding an Opening to Resume Dialogue

As of March 2023, the average age of former residents of Northern Territories was 88.5 years old. Their total population in Japan has also decreased to 5,135 former residents, about 30% of what it was at the end of World War II. A pessimistic outlook has spread among former residents regarding whether they will live to see the day that the islands are returned to Japan.

Tsunoka Yasuji (87) is active in the local community and is a native of Yuri Island in the Habomais. Head of the Nemuro branch of the Chishima Renmei, Tsunoka says that he is “of course naturally angry at Russia” but also “disappointed that the Japanese government has not found a way to resume further dialogue.” Nevertheless, Tsunoka also notes that “anger won’t get us anywhere. Territorial negotiations will be difficult unless relations between Japan and Russia improve. I want both sides to refrain from actions that could provoke each other.”

Professor Iwashita Akihiro of the Slavic-Eurasian Research Center at Hokkaidō University believes that “a ceasefire in the war in Ukraine will eventually come and this will be a chance to resume full-scale dialogue.” Professor Iwashita notes that while Japan and Russia are at odds with each other in various areas of the bilateral relationship, there is also “an urgent need for discussions on disaster response and maritime safety and fisheries, and on visions for the Northeast Asia region as a whole.” Noting that Japan and Russia are neighbors, Professor Iwashita emphasizes that they have no choice but to stay in contact. “Therefore, we should already be preparing for the next opportunity that presents itself to improve relations. Even though major barriers to reactivating negotiations over the Northern Territories have been erected in recent times, I believe that future exchanges and visits to graves could be resumed.”

(Originally written in Japanese on April 24, 2024. Banner photo: The Northern Territories spread out from Cape Nosappu on the Nemuro Peninsula, Hokkaidō, at lower left. © Kyodo.)