Japanese Jeans Turn Sixty: Visiting Okayama’s Denim Capital, Kojima

Society Economy Fashion- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Cotton at the Industry Core

The Kojima region in Kurashiki, in what is now Okayama Prefecture, is no fresh arrival to importance in Japanese history. It gets a mention in Kojiki, the oldest surviving Japanese-language text. While Kojima is now connected to the mainland, it used to be an island, as the –jima in its name suggests. Over time, land reclamation, combined with the accumulation of sand deposited by local rivers, transformed the area into a vast plain.

Widespread land reclamation in the Edo period (1603–1868) made the soil of Kojima salty and unsuited for rice production. Farmers therefore cultivated cotton instead, which has better salt tolerance. Cotton produced here was woven into cloth for sails and socks, of which Kojima was the most important production center. From the Edo through the Meiji –periods, sailcloth produced in Kojima was used extensively on the kitamaebune sailing ships that plied the Sea of Japan, connecting Osaka and Hokkaidō. Basically nondyed canvas, sail fabric provided the foundation for Japan’s first locally made jeans.

History of Kojima and Domestic Denim Production

712

The place name Kojima appears in the Kojiki.

Edo Era (1603–1868)

Cotton cultivation and sail production takes off.

Meiji (1868–1912)

Kojima produces canopies and workwear.

Early Postwar (1945–60)

School uniforms dominate output.

1965

Kojima produces first Japanese-made jeans.

1980–

Market becomes more competitive with influx of imported jeans.

1990s–

“Vintage” jeans gain popularity, focusing attention on high end of market.

Compiled by the author.

In the Meiji era many cotton mills opened around Kojima, producing tents, truck canopies, and workwear. After World War II, cotton school uniforms, of which Kojima was the greatest producer, came to dominate production. Hundreds of years of a thriving cotton industry also made Kojima the repository of significant expertise in sewing.

Forced to Change Course

However, this cotton powerhouse would soon be flung into crisis. In the latter half of the 1950s, Japanese manufacturers began producing a new fiber called “Tetoron” (polyester). A revolutionary material claimed to be “finer than silk and stronger than steel,” Tetoron proved to be a disruptive innovating force in the industry.

As Tetoron school uniforms became all the rage, sales of their cotton counterparts plummeted. Major clothing label Maruo Hifuku (now “Big John”) was left with warehouses overflowing with unwanted cotton uniforms. Not knowing what to do, CEO Ozaki Kotarō turned to jeans (often called jīpan in Japanese, a linguistic borrowing from the G in GI, the American military members stationed in the country), which at the time were a major hit in Tokyo’s Ameyoko shopping district.

An imported American 1960s Union Special sewing machine, capable of sewing rolled seams. (Courtesy Betty Smith Jeans Museum)

Ozaki procured a pair of US-made jeans and meticulously examined the fabric and stitching. With its years of sewing experience, Ozaki believed his company had what it took to produce the new garments. However, he had never seen denim before. Maruo Hifuku also lacked the metal rivets used to reinforce jean pockets or metal buttons and zips, not to mention thread suitable for sewing thick cotton fabric, or, for that matter, the right kind of sewing machines. Ultimately, it was only after importing most of these supplies from the United States that Maruo Hifuku was finally able to start making jeans in April 1965.

The young women working in this 1970s jeans factory lived in company dormitories. (Courtesy Betty Smith Jeans Museum)

Growing the Brand

Ozaki was short in stature, even for a Japanese person, and his given name, Kotarō, could be rendered as “Little John” in English. Feeling that this sounded like a brand for children, Ozaki’s product development team eventually settled on “Big John” instead for their brand name.

The first Japanese jeans were manufactured in 1965 under the Big John brand. (Courtesy Betty Smith Jeans Museum)

Over time, jeans came to enjoy broad support that transcended class, age, and gender. However, it was actually Ozaki’s focus on gender differences that led to the creation of the women’s jeans brand “Betty Smith.” This was followed by the “Bobson” line, which was established in 1969 as the little brother of the Big John brand. This positioning-based brand strategy, unusual in Japan at the time, proved highly successful.

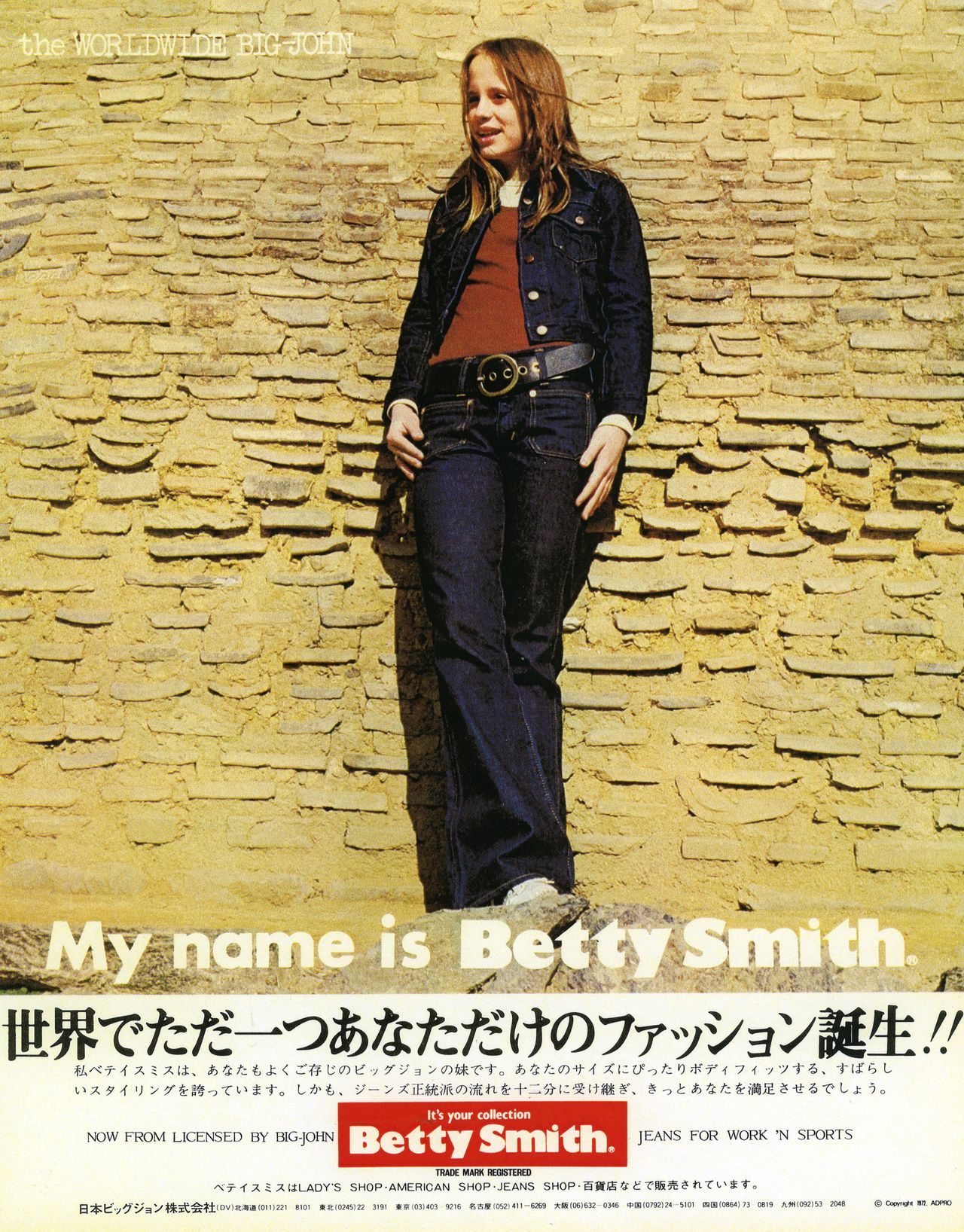

Betty Smith, Japan’s first women’s jeans brand, was launched in 1970. (Courtesy Betty Smith Jeans Museum)

An advertisement for Betty Smith jeans from the 1970s. (Courtesy Betty Smith Jeans Museum)

Interestingly, Big John advertised and marketed these brands as if they were from California. Beginning in the 1970s, Japan’s textile industry became less competitive due to US-Japan trade friction, the increasingly strong yen, and the industrialization of developing nations, causing the Japanese market to be flooded with jeans imported from the United States and other markets. Now that they had been introduced to the real McCoy, Japanese consumers also became choosier. Kojima’s jean manufacturers were forced to differentiate themselves from their competitors.

Building on the Region’s Original Strengths

While Japanese clothing manufacturers initially sourced their raw materials from the United States, Kojima’s makers began to explore ways to bring their production focus to a more local level, from materials to crafting methods, early on. As discussed above, the changing business environment also encouraged Kojima jeans manufacturers to innovate.

What was traditionally called the Sanbi region (comprising the old domains of Bizen, Bitchū, and Bingo that span today’s Okayama and Hiroshima prefectures), has for hundreds of years had a large indigo dyeing industry, and it was this experience that enabled a smooth transition to modern-day indigo dyeing. Hiroshima-based textile manufacturer Kaihara, one of the first to make indigo-dyed denim, is now an internationally renowned company with an over 50% share of the domestic market.

According to the Japan Cotton and Staple Fiber Weavers’ Association, which represents the cotton textiles industry, a total of 23.9 million square meters of denim were manufactured in the Sanbi region in 2023, representing almost 100% of Japanese made denim. Renowned jeans manufacturers from around the world love the product for its quality and uniqueness. Kuroki is a denim manufacturer based in Ihara, to the west of Kurashiki, that has partnerships with the world’s largest luxury brand, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, and has received praise for its incorporation of traditional Japanese weaving techniques.

Denim manufactured in the Sanbi region travels to Kojima to be made into high-quality jeans. This is because, as noted above, the region is home to a large workforce of skilled textile workers, as well as to the craftmanship and attention to detail that have been passed down from generation to generation. At the heart of Kojima-made jeans are pattern-cutting technologies that make jeans better fitting, and over 200 years of technological innovation in stitching thick cotton. Denim garments shrink slightly over time, a property that Kojima’s jean manufacturers have successfully transformed into a comfortable fit through the application of expertise in patterns and stitching.

Stitching techniques passed down through generations are the secret of Kojima-made jeans’ comfortable fit. (Courtesy Betty Smith Jeans Museum)

Kojima manufacturers have also continually tried to avoid falling into the trap of mimicking established overseas brands like Levi’s, time and time again creating new value. Their washing techniques are a prime example. Wash processing makes jeans softer and more comfortable to wear.

To date, textile manufacturers have developed a variety of wash processes, including stone washing, in which denim garments are put in a washing machine with pumice and abrasives; chemical washing, in which garments are treated with bleach and other additives; and bleaching, in which oxidants and reductants are added to fade the fabric. Another manufacturing technique that enables makers to add value is “distressing,” in which fabric is sandblasted or otherwise intentionally damaged. As well as enabling Kojima-based manufacturers to differentiate themselves from overseas brands, these techniques have also led to the creation of new trends in jeans fashion. The world-leading refinement of these techniques is the reason that many overseas brands of jeans are produced in Kojima.

A World Denim Leader

Let us consider what needs to be done to enable the continued development of the Kojima jeans industry. It is possible to identify five main areas where work is needed.

- The merging of traditional craftsmanship with technological innovation

- The enhancement of branding

- Tie-ups between industry and tourism

- Environmental measures

- Reuse and recycling

With regard to technological innovation, the distressing process is now being performed by lasers, as the merger of this new technology with traditional technologies opens up new markets. When it comes to boosting the “made in Kojima” brand, we can learn a lot from the Swiss watch industry, which pulled off a successful revival in the 1980s through clever marketing. Harnessing tourist attractions like “Jeans Street,” which is filled with jeans proprietors, and the Jeans Museum, which showcases the history of Kojima’s jeans in a way that shares the appeal of the local jeans culture with a large audience, will win new fans.

This unique sign greets visitors to Kojima Jeans Street. (Courtesy Kojima Chamber of Commerce and Industry)

This manhole on Kojima Jeans Street features a characteristic logo and orange stitching. (Courtesy Kojima Chamber of Commerce and Industry)

It goes without saying that ongoing efforts to manage the large quantities of water and chemicals consumed in the manufacturing process are essential, in addition to other environmental commitments. As textile waste increasingly becomes an issue internationally, initiatives for the reuse of unwanted jeans will become even more important.

According to Ōshima Yasuhiro, former chair of the Kojima Chamber of Commerce and president of Betty Smith, “In addition to being the home of Japanese-produced jeans, Kojima needs to retain its leading position as a manufacturer of the world’s most global uniform.”

In order to resolve these issues and make Ōshima’s aspirations a reality, the fostering of workers who will carry on the craft, as well as engineers who will bring about future innovation, is a matter of urgency. The industry also needs a new entrepreneurial figure to carry on Ozaki Kotarō’s legacy of plotting and executing a path for the future.

The street remains a popular destination for visitors. (Courtesy Kojima Chamber of Commerce and Industry)

References

The author referred to the following works in preparing this article.

- Christensen, Clayton M., The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, Harvard Business School Press (1997).

- David, Paul A., “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY,” in American Economic Review, Vol. 75 No. 2 (1985).

- Heldt, Gustav (trans.), The Kojiki: An Account of Ancient Matters, Columbia University Press (2014).

- Porter, Michael E., Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, Free Press (1980).

- Porter, Michael E., The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Free Press (1990).

- Schumpeter, Joseph A., The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle, Harvard University Press (1934).

- Sugiyama Shinsaku, Nihon jīnzu monogatari (The Story of Japanese Jeans), Kibito Publishing (2009).

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A display of jeans welcomes visitors at the entrance to the Kojima Jeans Street. © Kojima Chamber of Commerce and Industry.)