Manga Ambassador Frederik Schodt: From Tezuka Osamu to the Age of AI

Entertainment Manga Anime- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Manga Goes Mainstream

Japan’s manga and anime have been making quite a splash in the United States for some time now, and are wielding growing influence in various areas of American culture. Anime works are streamed on Netflix, manga and anime characters are featured in New York’s Thanksgiving Day parade, and these artforms have even been referenced as an inspiration for films like the 2022 Everything Everywhere All at Once, which won numerous Academy Awards the following year.

For anyone who lives in the United States, it is clear that the popularity of manga and anime knows no bounds. A visit to any bookstore will be evidence of that.

The public broadcaster PBS reports that US sales of manga rose fourfold from 2019 through 2022, making up the fourth-largest fiction genre after romance, thriller, and fantasy titles. The boom is fueled by low-cost apps offering instant access to manga in English translation. Animated works are also broadly available on Netflix and other streaming platforms.

Manga sales are rising sharply, mainly among young people, who flock to independent booksellers. At one such shop in New York, for instance, manga are prominently displayed in the center of the sales floor.

A New York City bookstore with an eye-catching manga display. (© Kasumi Abe)

Frederik L. Schodt, a veteran Japanese-to-English translator with a five-decade-long career, notes: “In the United States, everyone knows the word manga. It’s even in the dictionary now. And thanks to being raised on anime like that of Miyazaki Hayao, young folks today are conversant with words like fusuma and tatami, which few people outside Japan knew fifty years ago.”

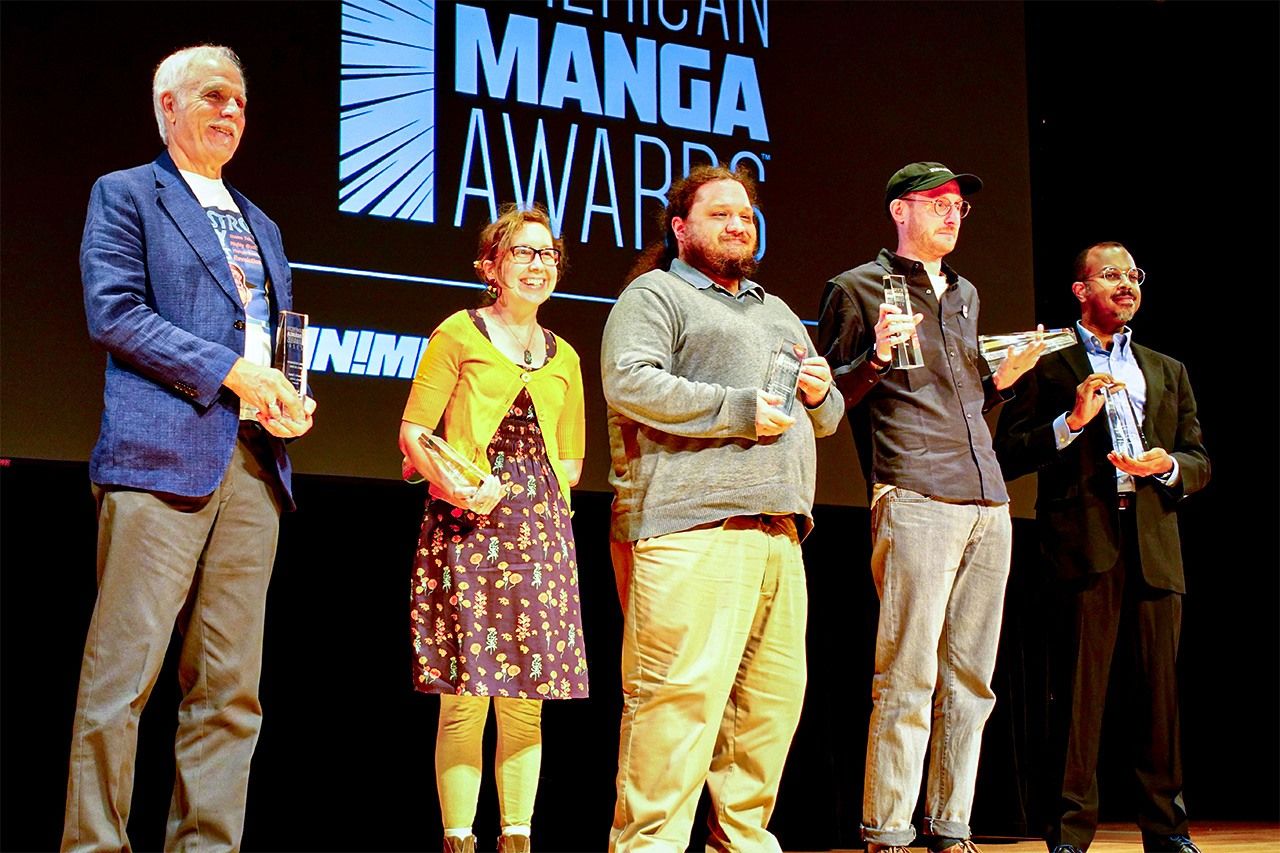

Having translated iconic works such as Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy) and worked on Hadashi no Gen (Barefoot Gen), Schodt was inducted into the Manga Publishing Hall of Fame at the American Manga Awards ceremony in New York City in August 2024 in recognition of his pioneering role in introducing manga to the North American market and laying the foundation for the current boom.

Frederik Schodt (far left) at the first American Manga Awards ceremony, in 2024. (© Kasumi Abe)

A Journey as a Translator of Manga

Schodt, whose father was a US foreign service officer, lived in Norway and Australia before coming to Japan at the age of 15 in 1965. After spending three years at the American School in Japan, he enrolled at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1968, but later spent two years living in Tokyo as an exchange student at International Christian University.

Graduating from UCSB in 1972, Schodt worked in various jobs, including as a dishwasher at a Japanese restaurant and as a guide for Japanese tourists. Back in Tokyo in 1975 as a graduate student on a Ministry of Education grant, Schodt returned to ICU to study translation and interpreting. Upon finishing his studies in 1977, Schodt began his career as a translator and interpreter, working at a language services company in Tokyo. Now living in the United States, he retains strong ties to Japan. His most recent visit there was in March 2025, as a member of the executive committee for the Japan International Manga Award sponsored by Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Schodt recalls his initiation into the field of manga translation. “In my first year at ICU, I was in the intensive Japanese language program, and I began reading manga as part of my studies. Manga was booming among university students at the time, and lots of them were carting around comics even thicker than their textbooks. Okada Shūichi, one of my dorm friends, came to my place one day and left five volumes of Hi no tori [which Schodt would later translate as Phoenix] with me, saying, ‘If you like manga, here, read these, but make sure you give them back!’

“I had been reading lots of comics aimed at young male readers, but Hi no tori blew me away with the quality of its storytelling and literary value. I realized then that manga was a medium equal to film and novels as a means of expression.” Of Tezuka Osamu, whom he later came to work with, he says: “Tezuka was a real intellectual, which is why he probably tried to make Hi no tori read almost like a work of literature.”

Friends he made during his second period at ICU provided the impetus for Schodt’s career as a translator. “Together with my pals Jared Cook, Ueda Midori, and Sakamoto Shinji, we formed a translation group named Dadakai to translate manga and bring Japan’s manga culture to overseas audiences. At the time, I was working at the translation company Simul International after finishing my graduate studies at ICU.”

Meeting Tezuka Osamu

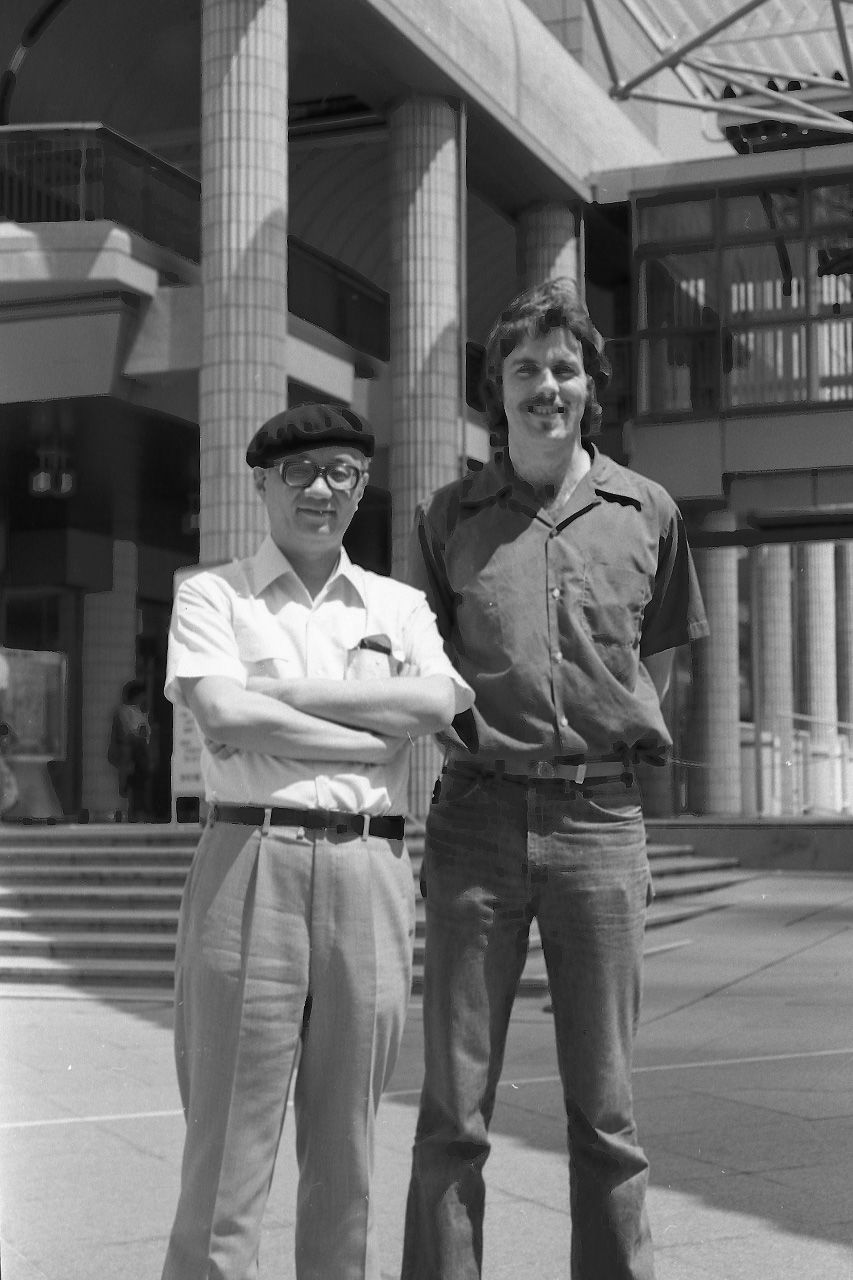

Schodt met Tezuka himself in 1977. The Dadakai members had decided that they wanted to translate a manga they loved, and they settled on Hi no tori. Through a connection of one of the Dadakai members, they decided to approach Tezuka Productions to pitch their idea.

“Tezuka was already very famous by then, so we certainly didn’t expect to meet the man himself. But as we were talking with his manager, he suddenly appeared and asked what we were there for. After we had explained our mission, the chance to have his work introduced abroad piqued his interest, and he okayed our project on the spot.” Thus began Schodt’s relationship with the “god of manga.”

“Tezuka-sensei was a very interesting character who already had plenty of overseas experience. Tetsuwan Atomu had already been aired on US television as Astro Boy, so he had been to Los Angeles for events related to that. He’d also been dispatched to the 1964 New York World’s Fair as a reporter for a Japanese daily newspaper.”

The late Tezuka Osamu with Schodt. (Courtesy Frederik Schodt)

What was Schodt’s relationship with Tezuka? Was the master just a guide to the industry, or had they become friends? Schodt explains:

“I can say without a doubt that Tezuka-sensei had a major impact on my life. He was much older than me and already an icon in my mind, but he was very kind to me. I also traveled several times with him to the United States and Canada as his interpreter. He was just a bundle of curiosity, and we had endless enjoyable talks.

“I remember one major blooper. I met Tezuka-sensei at the San Francisco airport where we were to board a flight en route to a film festival in Canada. We started talking, and we were so engrossed in our conversation that we missed our plane! That was a real misstep on my part, but he just said ‘Never mind. Don’t worry about it.’ He could be tough on his family and his subordinates, but he was never anything but kind to me.”

The Global Manga Boom

When Schodt began his translation career in earnest, there was nothing like the manga boom the world is seeing today. He says, “My only thought was that it would be great if translating manga into English helped more people develop an interest in Japanese manga. I started seeing the beginnings of a real manga boom around the end of the 1990s. That was when US television began airing anime like Pokémon and Sailor Moon. All the kids suddenly caught Pokémon fever, and that’s when the tide began to turn.”

It is clear that anime was the catalyst for manga’s popularity. Crunchyroll, a major anime streaming service, is steadily rising in popularity, with 120 million registered users and over 150,000 paid-up members at the end of 2024. Manga are also flying off the shelves.

Schodt notes: “In the early days of anime, videotaped copies of anime programs made by fans were common. As the anime fan population grew, anime-related conventions began to be held. In the Internet age, scanlations—scanning and translation of manga by amateur fans—also proliferated, and there was an epidemic of pirated translations. All of these factors contributed to manga’s popularity.

“In the latter half of the 1990s, jisui—literally, ‘cooking for yourself,’ a manga otaku term referring to taking a manga apart to scan it page by page to create an ebook—was popular in Japan and abroad. Such ebooks reached a wide audience, although that’s blatant copyright infringement.”

Pirated works and scanlation were huge drivers of manga’s popularity, but deprived manga creators and publishers of revenue. The people sharing works with these methods, though, gave little thought to the fact that manga disseminated by those methods meant financial losses and raised ethical dilemmas.

AI’s Emergence and Its Impact on Translation

Today, new trends are impacting the industry, and AI in particular is making giant strides. The quality of AI-translated material can be quite high, leading some to believe that the traditional profession of translation is on the verge of disappearing. As for the future of translation, Schodt explains that “I’m not earning a living by translating manga exclusively; I also work as an interpreter and as an advisor for manga-related events. Frankly, I think that AI spells the end for translation as a profession.”

Schodt sometimes encounters aspiring manga translators at anime conventions, but feels he has to break it to them that that line of work just isn’t viable anymore. “There are already startups specializing in AI-assisted translation, and the quality of the work is vastly improving. I think we’re at a historic turning point. Eventually, 90 percent of translation will be done by AI, with humans relegated to the task of checking and fine-tuning the output.”

Manga in translation is a form of entertainment, explains Schodt; few in the field expect translations to be perfect. “In the entertainment field, people are satisfied with so-so translations. There are lots of scanlations done by amateurs, which fans are fine with. But illegally copied works really push down the fees that professional translators can earn. It’s simply become impossible to earn a living from translating manga only, unless those who do that are ready to put up with living in their parents’ basement and subsisting on instant ramen.”

Schodt addressing the audience at the first American Manga Awards in 2024. (© Kasumi Abe)

Schodt offers a ray of hope to those wishing to see the artforms continue to thrive, though. “When you live in Japan, it’s hard to realize just how much of an impact manga and anime have had elsewhere. But the genre is a powerful global force: The Japan International Manga Awards for 2024 received 716 entries from 95 countries and territories, the largest number ever. A Brazilian won the Gold Prize, and the Silver winners were from Thailand, Taiwan, and Chile; their works were of professional quality. The number of entries, many of which were clearly influenced by Japanese manga and anime, has also risen sharply. I think that’s wonderful, and it’s a really good example of Japan’s soft power.”

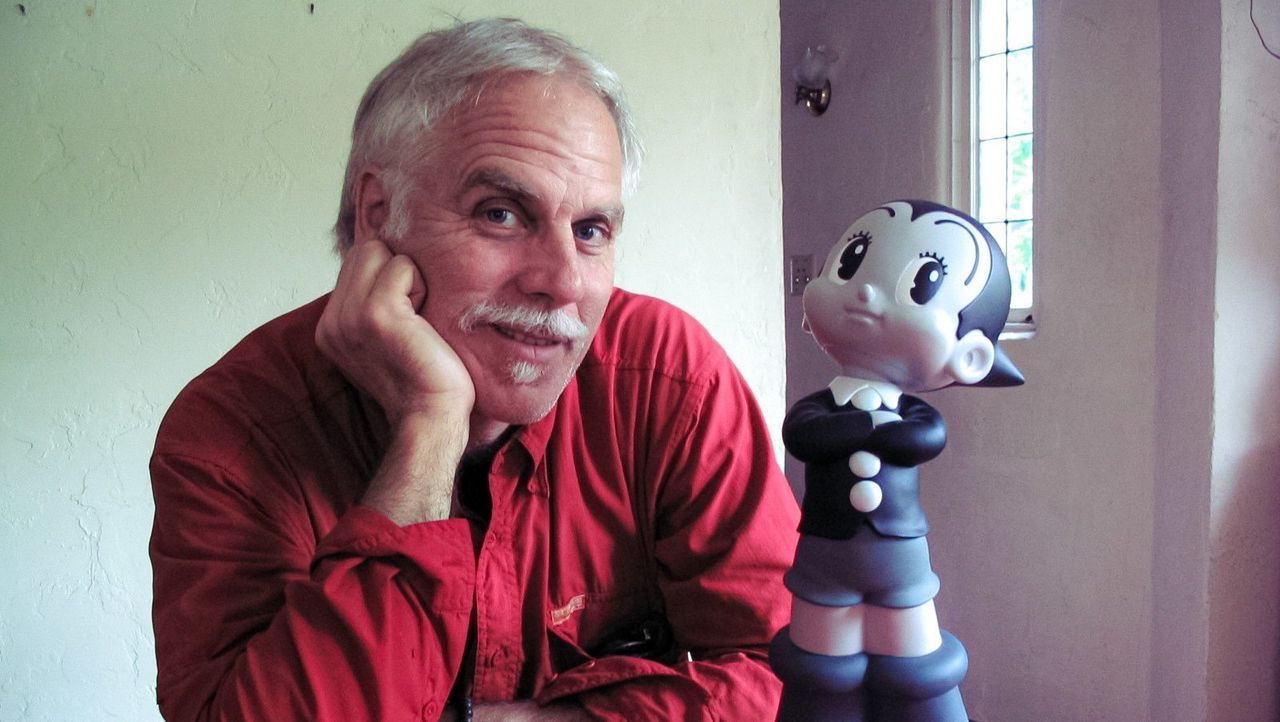

(Written in English based on an original Japanese text. Banner photo: Pioneering manga translator Frederik Schodt with his longtime companion, Astro Boy. Courtesy Frederik Schodt.)