Season of Disaster: Downpours and Heatwaves Becoming the Norm as Japanese Summers Get Hotter and Longer

Society Disaster Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Warming Oceans

As climate change pushes temperatures higher, July 2025 was one for the books in terms of heat. The mercury soared across Japan, averaging 2.89° Celsius above normal for the month to make it the hottest July on record. The sweltering weather was capped by Tanba in Hyōgo, which set an all-time national high of 41.2° on July 30; just a week later, on August 5, Isesaki in Gunma surpassed the mark, reaching a baking 41.8°.

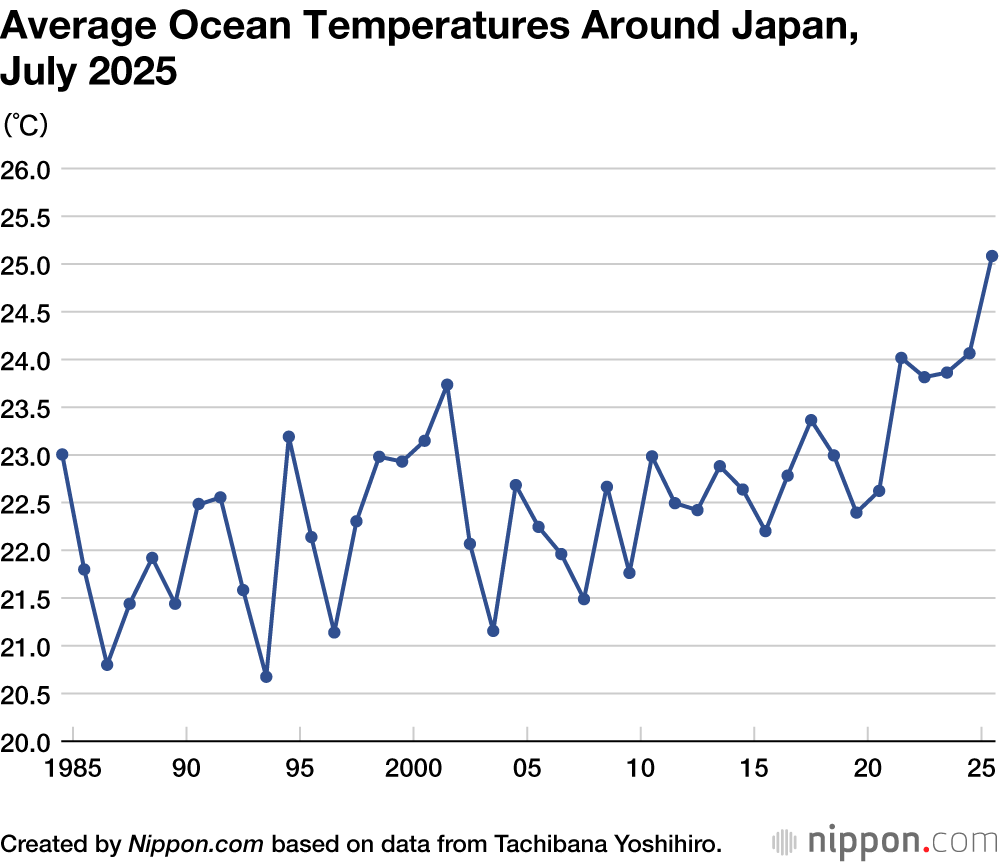

Japan’s scorching summers are the result of the North Pacific High, a high-pressure system that brings hot and sunny weather, and the Foehn effect, a phenomenon resulting in warm, dry conditions as air descends the leeward side of mountain ranges, often after having dropped its moisture on the windward side. This year saw an added driver of hotter weather in the form of high ocean temperatures, with the average for July exceeding 25°, fully 1° above the already high marks of the last few years. Sandwiched between warm air and warm seas, Japan baked mercilessly.

High-Seas Research

I tracked the precipitous rise in ocean temperatures firsthand as part of joint research by Mie University and the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC). From mid-June to early July, researchers on vessels from each institution took readings of surface ocean temperatures off the Pacific coast of Tōhoku in northern Japan. Astonishingly, the water temperature climbed 3°–4° degrees in a single week, with the unseasonal June heat pushing it past 20°, more than 5° above average for the time of year.

The warm conditions produced a band of nearly 100% humidity up to an altitude of one kilometer, triggering a nearly impenetrable fog. This so-called Yamase fog, long the scourge of farmers in region, is typically caused by cold, wet air from the northeast moving over the Pacific coast of northern Japan. However, the rapidly warming ocean surface gave this year’s fog a tepid character, as illustrated by the coastal town of Ōfunato in Iwate, which averaged a high of 23.5° in late June, a sweltering 4.3° above normal.

The author, right front, and researchers from Mie University prepare to release a weather balloon from a research vessel off Japan’s northeastern Pacific coast in June 2025. (© Tachibana Yoshihiro)

Caught in a Climate Change Vise

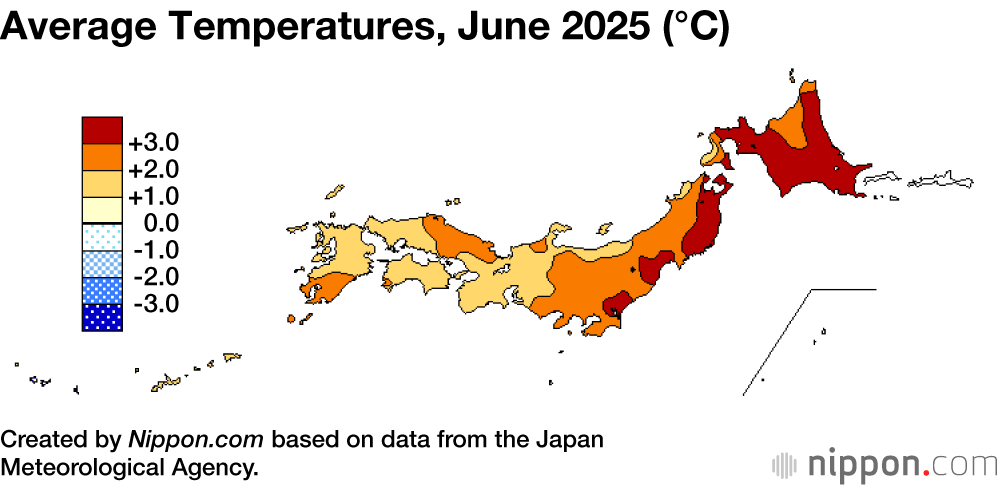

Analyzing the data clearly shows that hot weather in June set the stage for July’s heat wave. According to the Japan Meteorological Agency, the average temperature for June was a record-shattering 2.34° above normal. Ocean surface temperatures were likewise high, at 1.2° above the norm for the month, tying the record set in 2024.

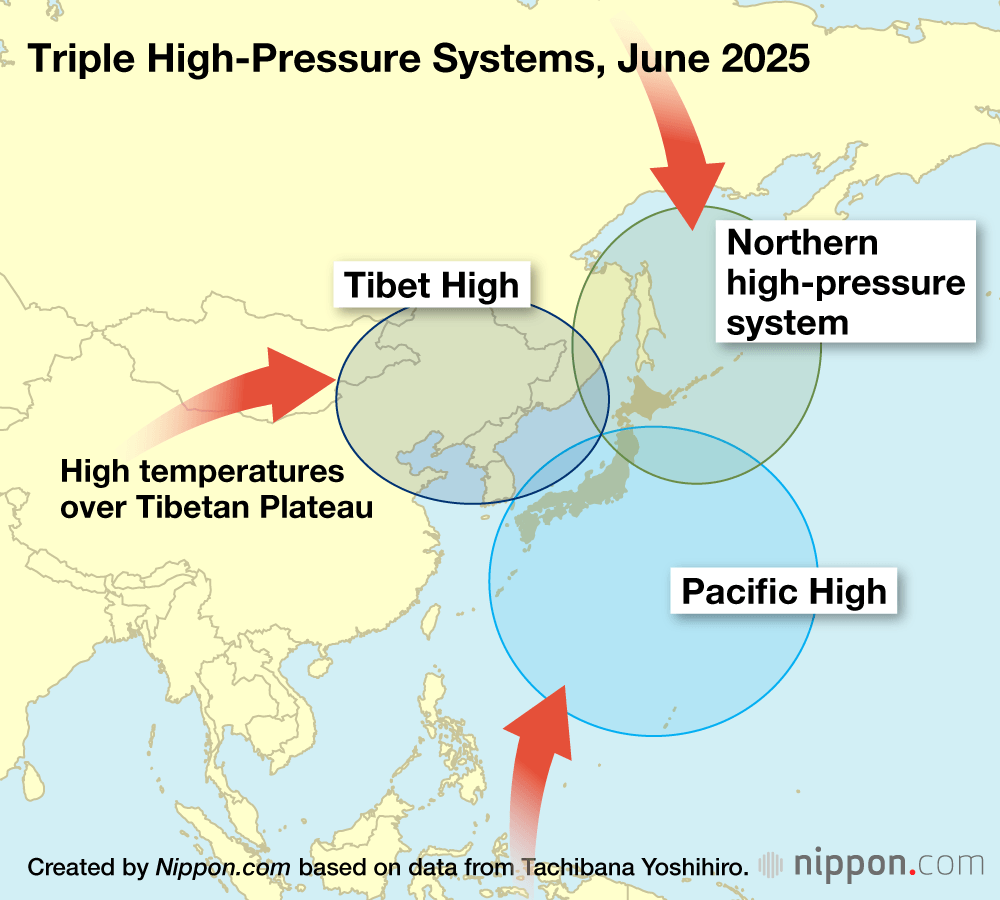

The baking June temperatures were the result of a trifecta of high-pressure zones that surrounded Japan, bringing an inflow of warm air that pushed the mercury to levels typically only seen in late summer. Needless to say, climate change is a major factor in the anomaly.

The Tibetan High, for instance, develops in the summer months over the Tibetan Plateau and Mongolia and influences Japanese weather patterns. However, accelerated snowmelt in those continental regions reduced the amount of sunlight reflected back into the atmosphere, allowing the ground to absorb more heat and driving up temperatures.

To the south of Japan, the Pacific High expanded rapidly, fed by abnormally high ocean temperatures spanning from the Philippines to the Indian Ocean, while the wildly meandering westerlies driven by Arctic warming trapped a high-pressure system that engulfed northern Japan in warm air.

June is when the summer solstice takes place, with the month’s long days bringing copious hours of daylight. But June also coincides with the rainy season in Japan, and the overcast skies help keep temperatures moderate by blocking sunlight. This year, though, the three high pressure systems brought an early end to the rainy season across much of the country, and without the shielding cloud cover, heat rapidly built up over land and sea.

The development caught experts off guard, as the JMA in May had initially forecasted a relatively mild summer. This prediction was based on the expected weakening of the warm Kuroshio Current, which typically flows northward from tropical latitudes along Japan’s Pacific coastline and branches into the Sea of Japan, helping drive warmer weather. However, June’s hot spell turned this moderate outlook on its head. Heat rapidly built over Japan and its surrounding waters, and the rise in ocean surface temperatures exceeded the expected effects of the weakened Kuroshio, forcing meteorologists to greatly adjust their prediction, warning instead that the impact would last well into October.

Growing Risk of Severe Rainstorms

As climate change warms the oceans, it releases more and more water vapor into the atmosphere. When low-pressure systems or weather fronts pass over the ocean, they readily soak up this moisture, raising the risk of flooding and other disasters when dumped on land in the form of torrential rains. Large swaths of Japan already face the threat of localized heavy rainfall, and as the waters off of Tōhoku warm, this risk has extended northward to threaten every corner of the country.

Japan has four main categories of heavy rain events. The first, yūdachi, are sudden showers that occur in the late afternoon and early evening on hot summer days. They are typically of short duration and have a low disaster risk. Similarly, so-called guerrilla rainstorms (gerira gōu) are localized thunderstorms lasting one to three hours, with their longer duration and intensity known to cause flooding in low-lying urban areas. More dangerous are training rainstorms (senjō kōsuitai), narrow bands of towering cumulonimbus clouds, also known as “thunderheads,” that dump huge amounts of rain over focused regions, lasting 6 to 12 hours at a stretch. Finally, there are seasonal weather fronts, which can trigger intense rain for long periods over a wide area and are a major cause of flooding and related disasters.

Types of Rainstorms

Afternoon showers

- Duration: around 30 minutes

- Range: localized

- Disaster risk: low

Guerrilla rainstorms

- Duration: 1–3 hours

- Range: localized

- Disaster risk: moderate

Training rainstorms

- Duration: 6–12 hours

- Range: concentrated over a long, narrow band

- Disaster risk: high

Weather fronts

- Duration: 12–24 hours, or longer

- Range: wide

- Disaster risk: high

Flood waters from rainstorms inundate temporary housing for victims of the Noto Peninsula earthquake in Wajima, Ishikawa, on September 22, 2024. (© Jiji)

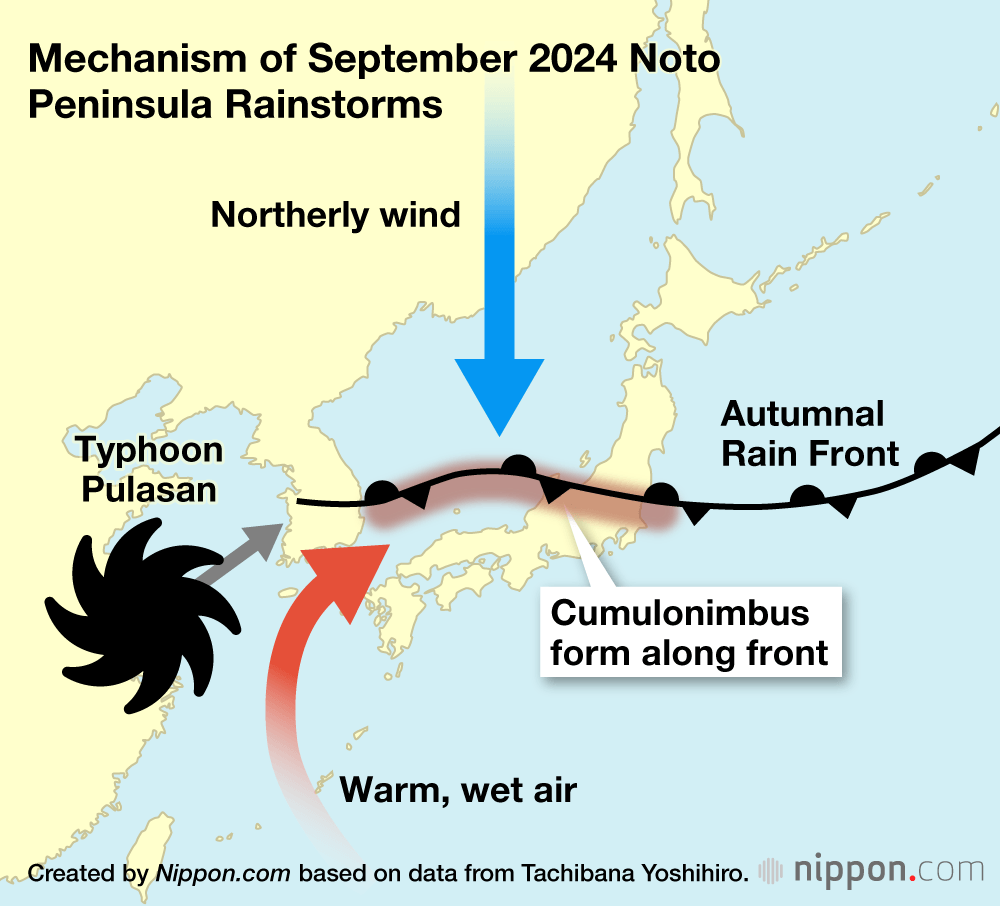

These different categories of weather event can occur in concert, posing an especially large risk of disaster. In September 2024, for instance, training rainstorms from a stalled weather front besieged the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa, adding to the woes of victims of a major earthquake that had struck the previous January. At the time, the surface temperatures of the Sea of Japan had climbed to as much as 5° above average in a phenomenon called a marine heatwave, releasing a torrent of water vapor into the atmosphere that engorged rain clouds and fell back to earth in a deluge.

Another destructive example was the torrential rains that swept across western Japan in July 2018. The heavy rainfall was fueled by the inflow of moist air from the remnants of a typhoon and humidity from the Pacific Ocean interacting with the tsuyu rainy season front. The prolonged rains caused flooding and landslides across multiple prefectures, with Hiroshima, Okayama, and Ehime being hit particularly hard.

The phenomenon is not limited to Japan, either. A similar effect of warming oceans supercharging weather fronts is behind unprecedented rain events around the globe, such as the deadly floods that devastated parts of Spain in 2024.

Meandering Typhoons

The effects of the changing climate also manifest in the unusual paths of typhoons. I describe in my recently published book Ijō kishō no mirai yosoku (Predicting Extreme Weather) how tropical storms are deviating from normal courses with greater frequency, making U-turns, zigzagging, and meandering across the seas in a drunken fashion. Such typhoons have stymied even the latest predictive technology, such as this year’s Severe Tropical Storm Krosa in July, which fitfully changed directions before eventually skirting the Kantō region.

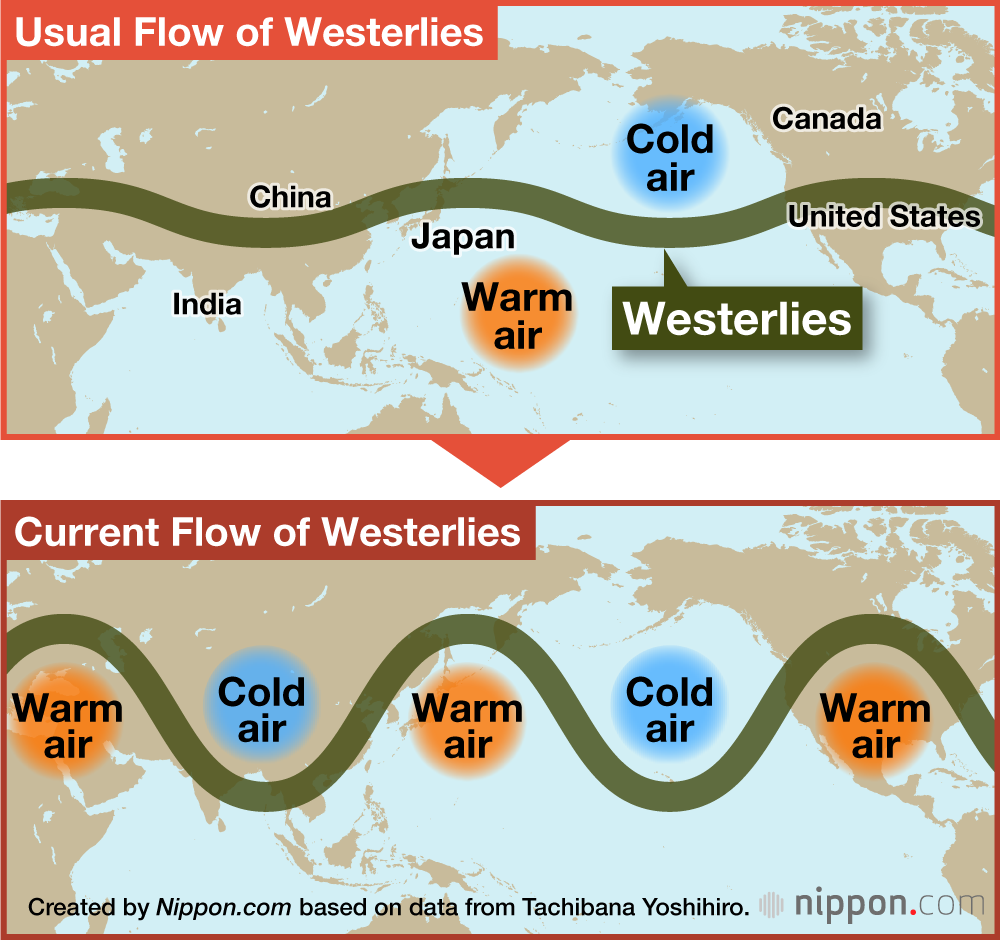

Climate change has complicated the ability to predict the course of typhoons by disrupting the meandering flow of the northern westerlies, strong east-to-west winds in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. The undulating tendencies of the westerlies increase or decrease depending on how fast the river of air flows. When there is a large difference in temperature between the poles and the equator, their speed increases and rippling is minimal, whereas the winds slow as the temperature difference narrows, intensifying the snaking effect. As the Arctic has warmed, the meandering of the westerlies has steadily become more pronounced, resulting in deep ridges.

These ridges influence the path of typhoons as they near Japan, with the blustery northern bends of the westerlies producing calmer winds over Japan, slowing the progress of tropical storms and causing them to move unpredictably. The effect is not unlike the way a leaf floating in a stream can undulate wildly when caught in an eddy.

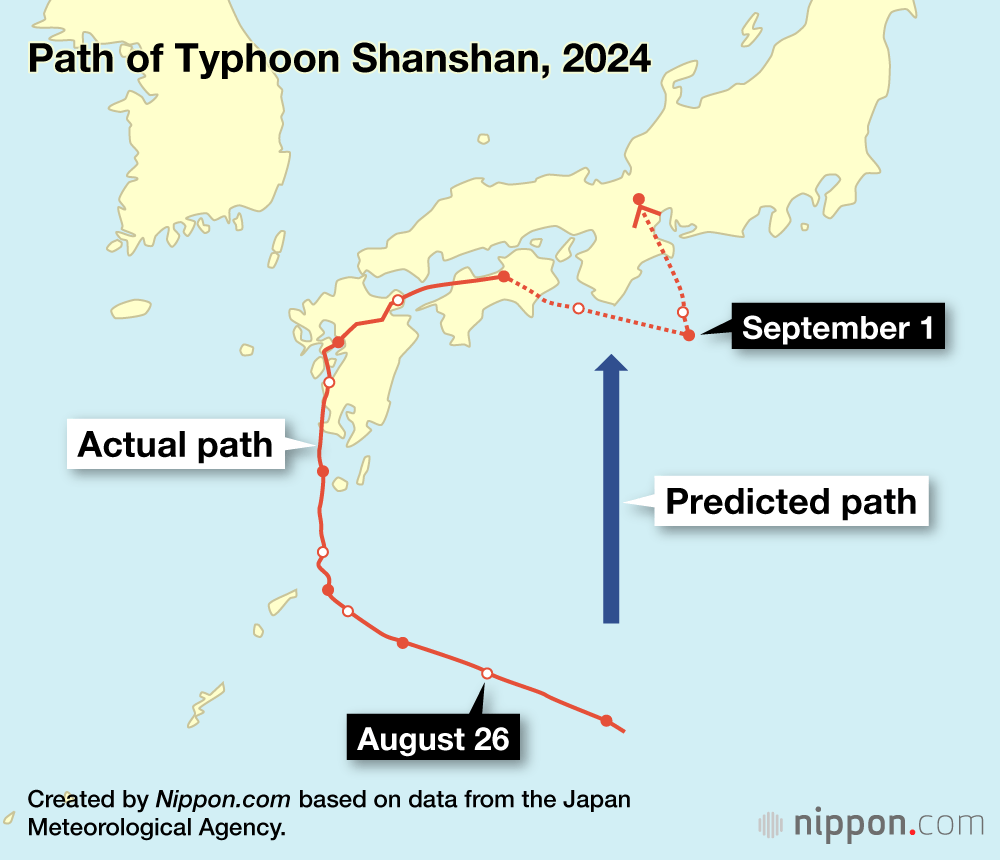

An extreme case of this was Typhoon Shanshan in 2024. The storm initially approached the coast of Japan in late August on a course for the Kii Peninsula in the Kansai region. However, it veered to the west and then north, eventually coming ashore over Kyūshū. From there, it followed an arching path over the Seto Inland Sea and the island of Shikoku before heading back out to sea in a southerly direction, where it abruptly turned north and made land again over the Kii Peninsula. Although Shanshan weakened to a tropical storm over Shiga, it hovered around Japan for a week, lashing it with wind and rain and disrupting transportation networks, including stopping the Tōkaidō Shinkansen for a three-day stretch.

Typhoons typically weaken as they make their way north. However, as the Kuroshio Current warms, pumping out the water vapor that fuels the storms, there is greater likelihood that slow-moving typhoons will maintain their strength or even grow in intensity as they spin across the North Pacific.

As global warming progresses, it is vital that people understand that the effects of the phenomenon extend far beyond merely a rise in temperature, but impact a wide array of weather patterns that directly affect our daily lives. As the warming of the atmosphere continues unabated, we can expect more and more severe weather events like intense rainstorms and meandering typhoons, bringing with them a greater risk of flooding and other disasters. Surely everyone can agree that such a future should be avoided at all costs.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner images © Pixta.)