Japan’s Overlooked Ethnic Diversity

People Society Culture Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Monoethnic Myth

Shimoji Lawrence Yoshitaka clearly remembers the first time he became aware of himself as potentially belonging to a “minority” within Japanese society. He was a university student at the time, attending a lecture on diversity and multiculturalism.

“One of the guest speakers had a Japanese father and a Filipina mother. The talk discussed the various minority groups in Japan, living here under different residency statuses and with diverse roots, including Japanese-Brazilians and other communities from South America, and Zainichi Koreans. The speaker also mentioned ‘Amerasian’ children born to local mothers with fathers serving in the US forces, noting that they were particularly numerous in Okinawa.”

Shimoji’s mother was one of these Amerasians, born in 1950 to a local woman and a white member of the US Armed Forces based in Okinawa. His American grandfather was transferred to another unit and returned to the United States during his grandmother’s pregnancy. He later married an American woman and died in 1995. Shimoji’s mother never met her father.

“Until then, although I would describe myself as a ‘quarter’ American or say my mother was ‘half’ Japanese, I never really saw myself as part of a minority. But the word Amerasian suddenly made me feel that I had been put in a separate category from other ‘Japanese’ people. It brought on a bit of an identity crisis.”

This experience led Shimoji to focus his research on the lives and experiences of so-called “halves” and other mixed-race people in Japan, as he came to feel a growing sense of belonging to a minority himself. He was surprised to find that there was almost no prior research on the topic.

“An important part of the reason, I think, is the widespread perception of Japan as a monoethnic nation state. The reality is that Japanese citizens include people with roots in Korea, China, and other countries, as well as indigenous groups like the Ainu and native Okinawans. But because ethnic identity is not recorded in official statistics, it tends to remain invisible. This makes it difficult to carry out research on the lives of so-called ‘half’ and ‘mixed’ Japanese people.”

In spring 2024, Shimoji collaborated with Viveka Ichikawa, a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, on a survey that looked at discrimination and mental health issues among people with mixed ethnicity in Japan. Of roughly 450 respondents, fully 98% reported having experienced “microaggressions” (subconscious prejudice and discriminatory behavior in daily life) in everyday life, while 68% had experienced bullying or discrimination at school or elsewhere. Using the same questionnaire as the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare’s survey on mental health, they found that the proportion of those indicated as requiring medical attention or monitoring was more than five times higher than the national average. The survey highlighted the extent to which adequate care systems are still lacking for Japan’s minorities.

Empty Claims to Support Diversity

Although the government has made a show of promoting diversity and positive intercultural relations in recent years, Shimoji is skeptical about the sincerity of these efforts, and says they lack substance.

“The government uses ‘half’ and mixed-race people only when it suits them. The Tokyo Olympics in 2021 were a perfect example. They chose internationally famous athletes like tennis star Ōsaka Naomi, who lit the Olympic cauldron, and basketball player Hachimura Rui, who was one of the flag-bearers at the opening ceremony. They wanted to show off their commitment to diversity and inclusion.

“But at the same time, the government does nothing to investigate the situation that people with mixed roots find themselves in, and shows no awareness of discrimination as a problem. Even though Japan is a signatory to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and the International Covenants on Human Rights, the government has taken no steps to establish a human rights body, or to pass comprehensive legislation banning racial discrimination. Schools teach almost nothing about human rights. As a result, young people are easily swayed by simplistic messages and susceptible to populism.”

Shimoji points out that life has become even more difficult for people with international roots since the July election for the House of Councillors, when Sanseitō made significant gains with a campaign that promised to put “Japanese first.”

“Note that the pledge is not ‘Japan First’ but ‘Japanese first.’ It’s exclusionary and racist, clearly built on the idea of the Japanese as an ethnically ‘pure’ people, distinct from ‘foreigners.’ It’s an us-and-them mentality, rooted in racism.

“It worries me to see how the ‘Japanese First’ slogan is seeping into daily life like a catchphrase. I’ve heard that children are already repeating it. Now more than ever, we need language that makes Japan’s diversity visible and encourages people to do more to value it.”

Okinawans as an Indigenous Ethnic Group

After a long period based in Tokyo and three years studying in the United States from 2021, Shimoji relocated to Okinawa in August 2024 to explore his roots more closely.

As a result, he has been spending a lot of time recently thinking about the Okinawan people as a distinct indigenous group. In 2019, the government finally recognized the indigenous status of the Ainu people, but so far has not extended the same status to the islands of the south.

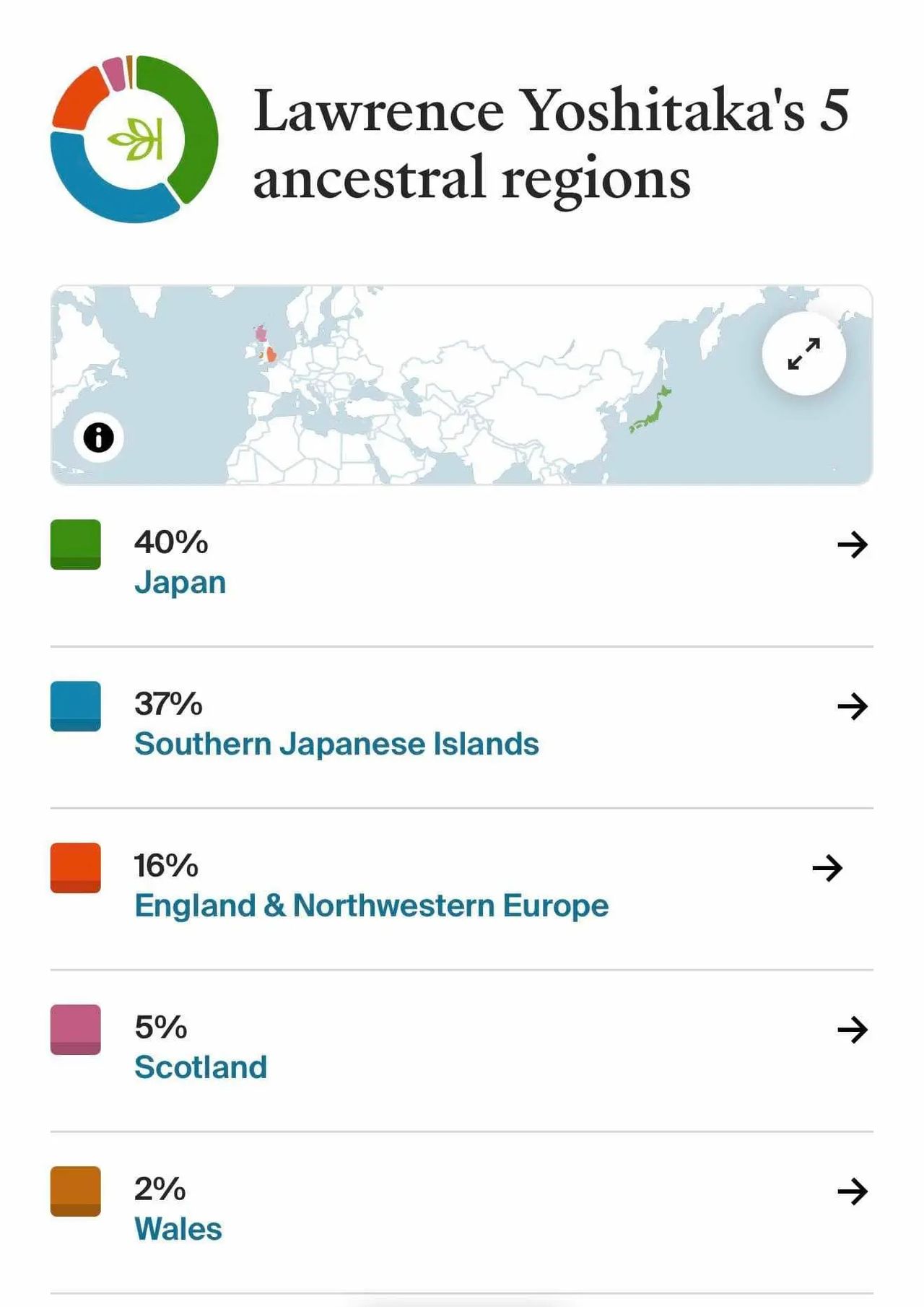

“Ishihara Mai, an assistant professor at Hokkaidō University whose work focuses on the Ainu people and their culture, describes herself as a ‘mix’ of Ainu and Wajin (Yamato Japanese) ethnicity. I had always thought of myself as a quarter Caucasian. But after a DNA test, I found that about 20 percent of my ancestry is ‘white,’ while Japan and “Southern Japanese Islands,” or Okinawa, account for around 40 percent each. I now see myself as a person of mixed ancestry with roots in an indigenous ethnic group.”

Shimoji Lawrence Yoshitaka’s ethnicity according to the results of a DNA test conducted by the Ancestry website.

In Okinawa itself, Shimoji says, although people strongly identify as Uchinanchu (Okinawans), discussion of an indigenous ethnic identity remains limited. “I feel that the government’s view of Okinawa has been internalized to a large extent within local society.”

Recently, he was disturbed by a news story about Okinawa Shōgaku High School, winners of the prestigious summer Kōshien baseball tournament in 2025. During the semifinal, supporters in Chondara costumes and face-paint based on the clown-like figure who appears in traditional Okinawan drama were a colorful presence in the stands. The Japan High School Baseball Federation apparently asked supporters to refrain from wearing “ethnic costume” and by the time of the final, these distinctive, uniquely Okinawan displays of support had disappeared.

“Think of rugby, where the All Blacks perform the haka, originating in an indigenous Maori war dance. If the Japan Rugby Football Union tried to ban the haka, it would be an international scandal. But in Japan, where Okinawans have no official recognition as an indigenous people, the incident went almost unnoticed, despite the huge media attention given to the tournament throughout the summer.

“The event reminded me that there is a persistent drive to erase Okinawan indigenous identity. The Ryūkyū Islands were once an independent kingdom. Today, Okinawa hosts a disproportionate number of US bases, and national security concerns mean the government is extremely wary of any moves toward independence. It feels as if a kind of colonial assimilation policy continues in place to this day.”

A New Generation of Writers and Artists

Shimoji’s aim is to smash the narrow view that equates “Japaneseness” with someone of stereotypically “Japanese” appearance, born to ethnically Japanese parents, and behaving in a conventionally “Japanese” way. While his mission continues, he says he finds reason for hope in the growing ability of a younger generation of minorities to make themselves heard.

“In the 1990s and 2000s, many so-called ‘halves’ became prominent as athletes, media celebrities, or fashion models, often singled out for their exotic looks or physical abilities. Today, we’re seeing more young people from diverse backgrounds asserting themselves across a wider range of fields.

“A rising generation of creators with roots outside Japan is making its mark. Writers like Andō Jose, who made his debut with Jackson Alone and won the Akutagawa Prize for Dtopia, and Fujimi Yoiko, whose manga Half-Siblings depicts the everyday lives of so-called hāfu in Japan, are gaining attention and acclaim.

Andō Jose (left) after winning the Akutagawa Prize in January 2025 (© Jiji), and the first volume of Fujimi Yoiko’s Hanbun kyōdai (Half-Siblings). (© Fujimi Yoiko/Torch Web)

Creative young people from diverse backgrounds are taking the initiative to express themselves within their own different genres based on their real-life experiences,” Shimoji says. “It’s encouraging to see them forging links through dialogues and collaborations. As more people take an interest in their work, my hope is that this will help promote greater awareness of the hidden diversity in our society.”

(Originally written by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com and published in Japanese on September 29, 2025. Banner photo © Pixta.)