Expression as a Crime: Hishiya Ryōichi’s Wartime Imprisonment Under Japan’s Peace Preservation Law

Society History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Shocking Arrests Under the Peace Preservation Law

The early twentieth century in Japan was a time of growing political, economic, and social uncertainty resulting from the country’s rapid modernization. It saw the rise of left-wing movements, and in response to these burgeoning challenges to the state the Japanese government passed the Peace Preservation Law in 1925 to guard the imperial system. In wartime, the suppressive legislation became a central tool for social control by curtailing liberties such as free expression.

In one of the most notorious examples of Japan’s wartime suppression of civil liberties, a small band of art students at a teaching college in Asahikawa, Hokkaidō, were imprisoned for depicting everyday scenes in their works. At 104 years old, Hishiya Ryōichi is the last living member of this group. He shares his ordeal of persecution for self-expression.

Even at well past a century in age, Hishiya recounts the traumatic events of his youth with clarity, calling his 1941 imprisonment by Japanese wartime authorities “a horrible experience.” He was a 19-year-old student when the military government incarcerated members of the art club for holding communist ideas. The incident is remembered as an egregious suppression of freedoms by the Japanese wartime government.

Hishiya had entered the Asahikawa Normal School in 1936 with hopes of becoming an art teacher. A curious and creative young man with a love of drawing, he joined the school’s art club. Along with his artistic pursuits, he enjoyed movies and would slip out of the school dormitory with friends to catch features not on the college’s curriculum. He was also an avid reader and was known to lose himself in the volumes he brought home from the local booksellers.

Hishiya Ryōichi (front left) and the other members of the art club at Asahikawa Normal School. (Courtesy Hishiya Ryōichi)

In January 1941, though, the carefree student lifestyle Hishiya and his art club friends enjoyed ended abruptly when their advisor, Kumada Masago, was arrested and charged with violating Japan’s Peace Preservation Law. Originally passed in 1925 to protect the imperial system from leftist ideologies, Japan’s wartime government had expanded the repressive legislation, enabling it to crack down on political thought and social movements it perceived as dangerous.

Hishiya says that the arrest of Kumada, who had been targeted by the authorities for encouraging his pupils to depict the actual lives of ordinary people in their artwork, was like a bolt from the blue. “I had never even heard of the Peace Preservation Law,” he recounts. “I was immature and didn’t accept what was happening.” His more astute classmates, though, were quick to discern the situation and warned that students would be next.

The pall that had fallen over the school grew even heavier as the army occupied the college, posting personnel around campus to monitor students and instructors. The military also took a heavy hand in the running of the institution. Hishiya was preparing to graduate, but to his shock, he and other members of the art club were ordered to repeat their final year of schooling on the grounds that they had been tainted by Kumada’s ideas.

Everyday Images

Although astonished by the order, Hishiya naively believed the situation would not get any worse. “I figured that as long as I didn’t make any waves I would be allowed to graduate,” he explains. But in the early hours of September 1941, eight months after Kumada’s arrest, three police officers entered the school dormitory and roused Hishiya and others as they slept. “They flashed a warrant and asked if I remembered Kumada. When I said yes, I was ordered to get my toiletries together.” The police arrested Hishiya and four other members of the art club, hauling them to prison as their dormmates looked on with concern.

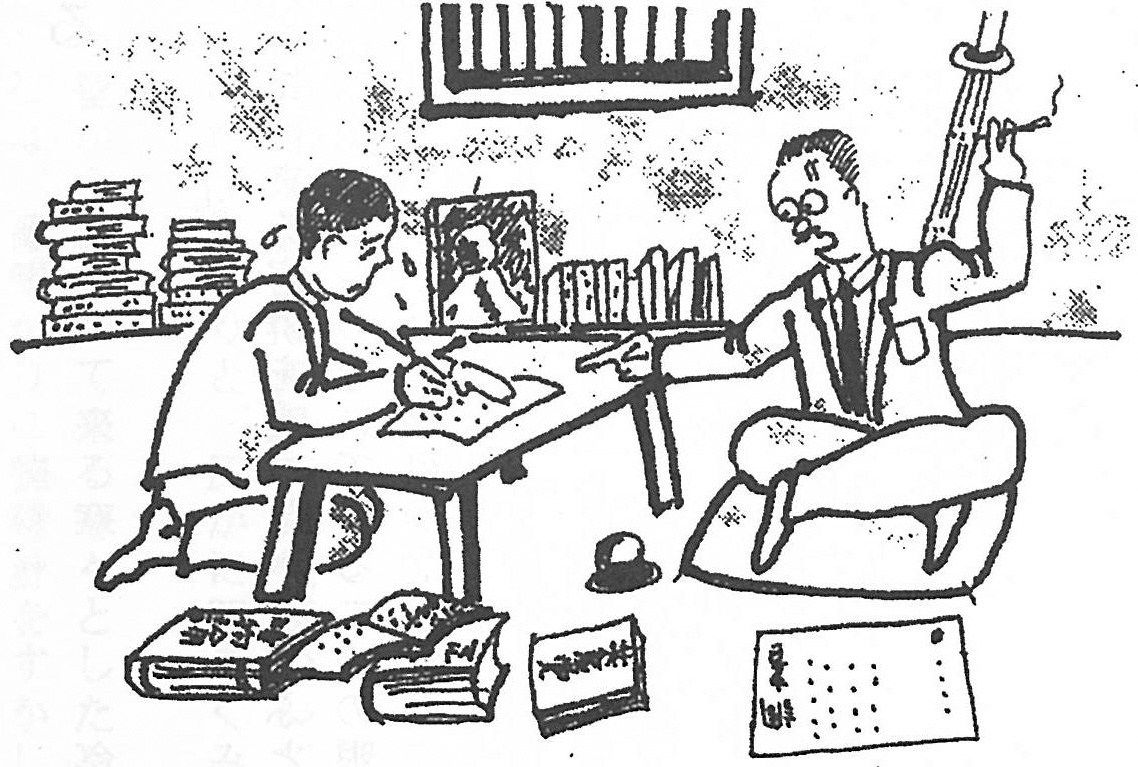

Hishiya documented his arrest in a sketch titled “The Police Come.” (Courtesy Hishiya Ryōichi)

The police interrogated Hishiya about one of his drawings, a scene showing two students discussing a passage in a book. The work had been part of an assignment to depict scenes of dormitory life, and the detectives’ suspicions focused on the book in the picture, which they declared to be a communist text.

Hishiya’s work depicting two people in deep discussion. (Courtesy Hishiya Ryōichi)

Hishiya vehemently refutes the accusation, declaring that “back then, I didn’t know the first thing about communism. I was merely re-creating moments from everyday life, much as Kumada had. All I wanted to show was that reading was an important part of the lives of young people.”

A Forced Confession

Held in custody at the prison in Asahikawa, the students endured harsh conditions. The police demanded they write statements admitting guilt and frequently resorted to violence, slapping or beating prisoners with bamboo swords to force them to confess. Hishiya complied with his captors and avoided such heavy-handed treatment, pleading guilty to the charges leveled against him under immense psychological pressure. “There wasn’t a word of truth in my written confession,” he says. “But it placated my interrogators.”

The police used the document to pressure Hishiya’s close friend Matsumoto Gorō, who was being interrogated at the same time. “They told Matsumoto about what I had written to coerce him into admitting guilt.” To their own surprise, they had become “communists.”

A sketch by Hishiya depicting the interrogation of a prisoner. (Courtesy Hishiya Ryōichi)

Hishiya would spend 15 months in prison. He suffered through the harsh Asahikawa winter, with the temperature dipping as low as minus 30° Celsius. The ordeal was made all the worse by knowing his family was just beyond the prison wall. “Our home was near enough to hear the bell rung each morning to wake the prisoners,” he recounts. “My mother and brothers eventually worked out that I was being held there.” In his despair, he says he even contemplated suicide by stabbing needles into his arm.

Legislation Deployed to Suppress Free Thought

The 1925 Peace Preservation Law was enacted in reaction to the 1917 Russian Revolution, an event that sent shockwaves across the globe. With the law, the Japanese government aimed to suppress ideologies that threatened the imperial system or denied private property. Historian Ogino Fujio, professor emeritus at the Otaru University of Commerce, explains that the wartime government used the law to roundup groups they saw as posing a threat. “Official records show that nearly 70,000 people were arrested in Japan under this law,“ Ogino explains. “Around a hundred of those incarcerated, particularly members of the Japanese Communist Party, were tortured to death, while several hundred more died from causes like psychological duress.”

Timeline of Events: 1917–45

1917

Russian Revolution

1925

Peace Preservation Law enacted

1928

First amendment of law makes death maximum penalty

1935

Japanese Communist Party effectively destroyed

1937

Sino-Japanese War begins

1941

Second amendment to law expands scope of persecution

Hishiya and others at Asahikawa Normal School arrested

Pacific War starts

1943

Hishiya sentenced to 18 months in prison (suspended for 3 years)

1945

End of World War II

Peace Preservation Law abolished by GHQ

Many of those persecuted under the Peace Preservation Law had no connection to communism. Like Hishiya, who vehemently denies ever supporting the communist movement, they were innocent victims of Japan’s march to nationalism.

Ogino notes that after 1935, when government crackdowns had effectively crushed the Japanese Communist Party, police units controlling political thought and expression began, in the guise of national security, to seek out new “subversive” targets. As the Sino-Japanese conflict intensified and Japan settled into its total war footing, they broadened their suppression activities to include social democratic and labor movements, liberals, new religions, and even Christians.

Ogino says that the Asahikawa Normal School incident illustrates the extent to which the government went to prevent dissent among the populace. “The authorities were concerned that in their depictions of everyday life, the students would lay bare the poverty and contradictions of society, providing an impetus to criticize the government and reinvigorate the communist movement.“ Ogino stresses that this period stands as an important lesson about the abuse of power by the state, noting that the government revised the law twice to broaden its scope and punishments. “Those in power could essentially direct the law against whomever they pleased.”

Hopes for Peace and Freedom

Hishiya was released from prison in December 1942 to await trial. He was expelled from the Asahikawa Normal School and eventually received an 18-month suspended sentence. Later, he was conscripted into the army’s replenishment forces.

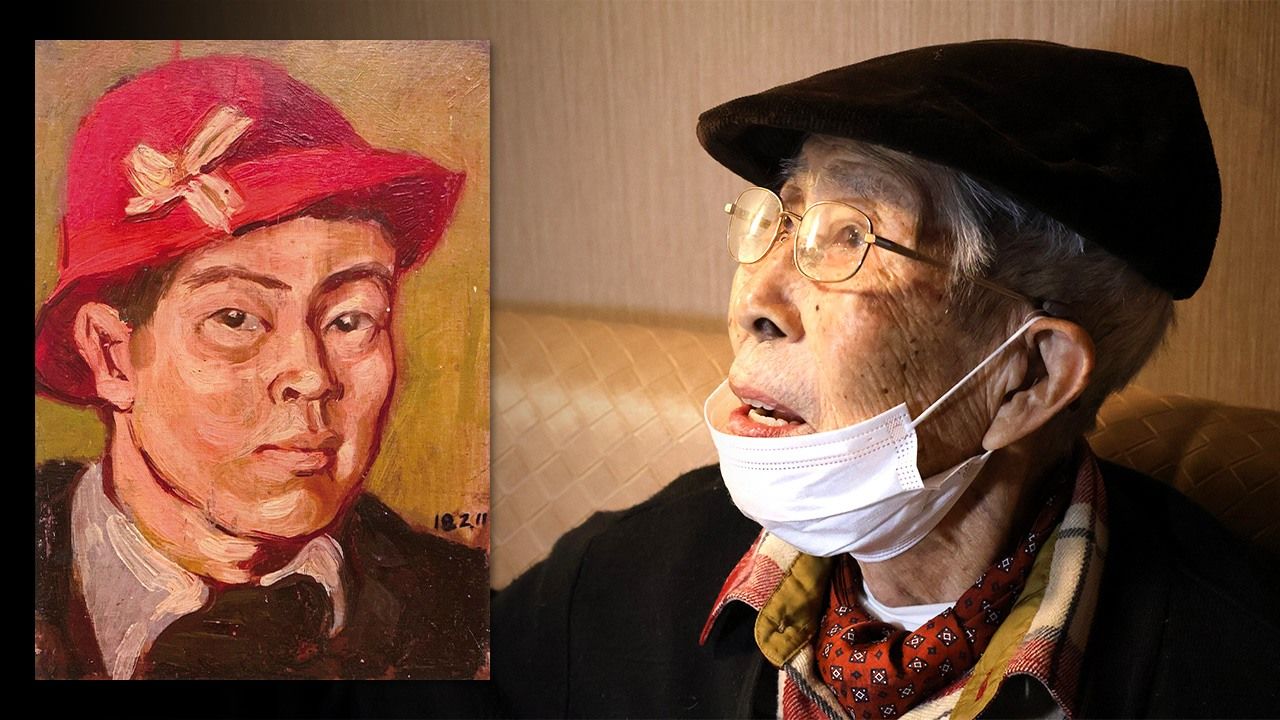

Fearing further abuse at the hands of the authorities, Hishiya did not speak out about his wrongful imprisonment, choosing instead to funnel his rage into his art. In 1943, he donned his sister’s red hat and painted a stirring self-portrait (shown in the banner image for this article) in a powerful mockery of the communist label he had been forced to wear.

At the end of the war, GHQ, the General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, quickly abolished the Peace Preservation Law. However, this did little to assuage Hishiya, who in his trauma remained silent about his ordeal for much of his life.

Through his father’s connections, Hishiya went to work for the energy company Asahikawa Gas, where he forged a successful career, retiring in 1979 as the director of a subsidiary. He married, raised a family, and dabbled in photography in his spare time.

He only returned to painting after retiring, seeing it as his life’s work. A turning point for him came in 1979 when he attended a gathering of his old art club friends. The group shared old stories and even spoke by phone with their former teacher Kumada. This led to a literary magazine, published in 1981, featuring essays, sketches, travel journals, and more. Estranged for so many years, Hishiya enjoyed renewing bonds with these old companions.

As the details of the incident at the Asahikawa Normal School slowly came to light in later years, researchers and citizen groups encouraged Hishiya to share his story. In 2006, he was visited at his home by the historian Miyata Han, and the two began reaching out to people related to the incident. As Hishiya opened up, the anger that he had suppressed for so many years welled up inside him, driving him to action. Since then, he has worked to clear the names of his friends and former classmates. He has traveled to the Japanese Diet every year with companions to petition the government for an apology and to demand state compensation for the victims’ families.

Hishiya Ryōichi. (© Mochida Jōji)

Having had his freedom and dignity taken away as a young man, Hishiya insists on staying abreast of political developments. When the coalition government led by the Liberal Democratic Party pushed through controversial provisions expanding the “conspiracies” class of crimes in organized crime legislation in 2017, Hishiya joined citizen groups in voicing his opposition. He saw parallels with the Peace Preservation Law, calling the legislation “troubling.”

Looking at the state of the world today, Hishiya says, “I’m a little anxious about whether we’re heading in a good direction. I want peace and freedom protected as basic rights, but it doesn’t feel like people enjoy them today. It’s like they’ve eroded away before our eyes.”

(Originally published in Japanese on December 15, 2025. Banner image: Hishiya’s 1943 self-portrait, painted shortly after his release from prison, showing him in his sister’s red hat; Hishiya during an interview at a hotel in Asahikawa on November 11, 2025. © Mochida Jōji.)