3.11: Japan’s Triple Disaster

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

When the earthquake hit on March 11, I was on the top floor of the University of Tokyo library. Books flew off the shelves, and young women’s screams echoed through the building. I evacuated the building and started to make my way home. No trains were running, of course, and I joined the growing flood of commuter “refugees,” making use of whatever means of transport I could find. It was nearly five hours later when I finally made it home.

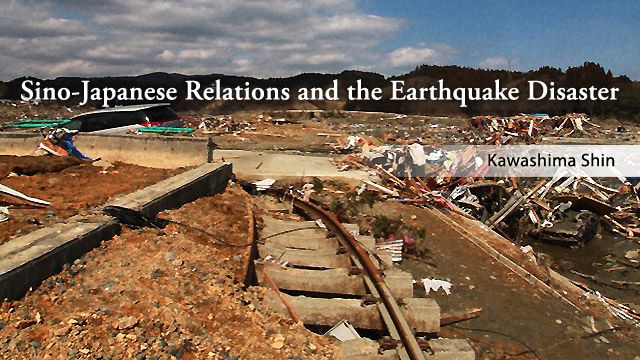

Nearly three weeks have passed since then. The catastrophe that Japan suffered on that fateful day was a triple disaster: the earthquake itself, the devastating tsunami that followed, and the ensuing crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. One of the distinctive aspects of this disaster is the way that, by and large, each of these three events has affected a different area and a different group of people. While strong vibrations measuring 5 or higher on the Japanese seismic scale were felt across much of northern Honshū, the tsunami that caused the majority of fatalities visited most of its damage on coastal areas, and serious fallout from the nuclear accident has so far basically been limited to an area within a 30-kilometer radius of the power station itself. The biggest victims, of course, are those who have been affected by all three events.

Over the course of the last three weeks, my work has taken me to Taipei, Beijing, and Shanghai. I received more than 100 messages of sympathy and concern in the days following the disaster, and have been met with words of encouragement and support everywhere I have been in the weeks that have passed since. I am extremely grateful for these words of kindness, of course, and have been touched by the fact that the lives of considerable numbers of foreigners were also affected by the disaster.

But I also have my doubts. Most of the people I have met overseas seem to be under the impression that the disaster took place within a single area; not many people seem to have grasped the multiple nature of the disaster and the wide range of different geographical areas affected by the earthquake, the tsunami, and the nuclear crisis.

My second reservation has to do with the way in which people have been giving aid, and the sentiment behind it. Because of the multiple nature of the disaster, the degree and type of damage vary dramatically from area to area, depending on whether the damage was caused by the earthquake, tsunami, or radiation. The types of assistance required are similarly diverse. Of course, we in Japan are extremely grateful for all the aid and assistance that continues to flow in from the Chinese-speaking regions and other parts of the world. But for this generous aid to be used as effectively and efficiently as possible, appropriate and prompt judgments are necessary, based on an accurate understanding of the situation.

This is the message I would like to convey to my friends overseas: People in the disaster areas will naturally tend to keep their emotions in check under an expression of gratitude. But there is and will continue to be a need for precisely directed aid, tailored to the needs of the moment. Ideally, aid decisions should be based not only on TV footage but on information gathered from the perspective of people on the ground and on meticulous ongoing communication with people in the affected areas.

(Originally written in Japanese on April 2, 2011.)