A Sumō Sandstorm Blows In from Egypt

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

It Takes More than Strength

INTERVIEWER What got you interested in sumō?

ŌSUNAARASHI When I was training at a body-building gym, someone told me that sumō was a very popular combat sport in Japan and that my sturdy frame was suited to it. My first training session was a bout with the slimmest person in the gym. He weighed 75 kilograms and I weighed 120, so I thought I could win even with one hand tied behind my back. In fact, I lost in less than two seconds flat. I fought five bouts and lost every time. My coach told me then that sumō isn’t just a matter of strength—it takes technique as well. It was really annoying but at the same time I felt attracted to sumō.

ŌSUNAARASHI When I was training at a body-building gym, someone told me that sumō was a very popular combat sport in Japan and that my sturdy frame was suited to it. My first training session was a bout with the slimmest person in the gym. He weighed 75 kilograms and I weighed 120, so I thought I could win even with one hand tied behind my back. In fact, I lost in less than two seconds flat. I fought five bouts and lost every time. My coach told me then that sumō isn’t just a matter of strength—it takes technique as well. It was really annoying but at the same time I felt attracted to sumō.

I had a look at the Internet and learned that there was a world of professional sumō, and that rikishi [sumō wrestlers] devoted their whole lives to the sport. Immediately I wanted to be a part of that world.

INTERVIEWER What sort of hardships did you have to face before your dream could be realized?

ŌSUNAARASHI Well, based on my strong desire to make it to Japan somehow, I started to chat on a sumō Internet message board. A member of the European Sumō Union offered to help if I was serious about it. But he warned me that junior rikishi had to follow the strict code of looking after the senior wrestlers. There might also be inconveniences from the point of view of religion.

ŌSUNAARASHI Well, based on my strong desire to make it to Japan somehow, I started to chat on a sumō Internet message board. A member of the European Sumō Union offered to help if I was serious about it. But he warned me that junior rikishi had to follow the strict code of looking after the senior wrestlers. There might also be inconveniences from the point of view of religion.

His warnings didn’t dissuade me, though, and I told him that I was determined to follow my dream, come what may, and that religion was a personal matter that wouldn’t stand in the way of that dream. When I added that I wanted to go to Japan right away, he said, “In that case, let’s discuss the details.”

INTERVIEWER When did you actually arrive in Japan?

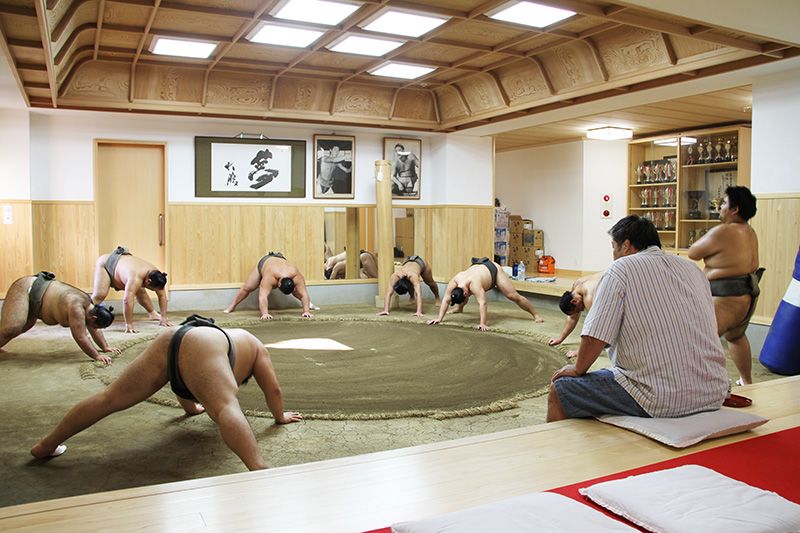

Training at the Ōtake stable starts at 7:30 in the morning.

Training at the Ōtake stable starts at 7:30 in the morning.

ŌSUNAARASHI I got here in September 2011. I thought it had already been decided which heya [sumō “stable”] I was to enter but apparently we had hardly any replies to the letter introducing me. So I had to call on many different heya to pay my respects and take part in the training there. The Ōtake stable was seventh on my schedule. When the oyakata [stable master] told me I could join his stable, I broke out in tears—it was the first step on the road to realizing my dream.

High Expectations for Himself

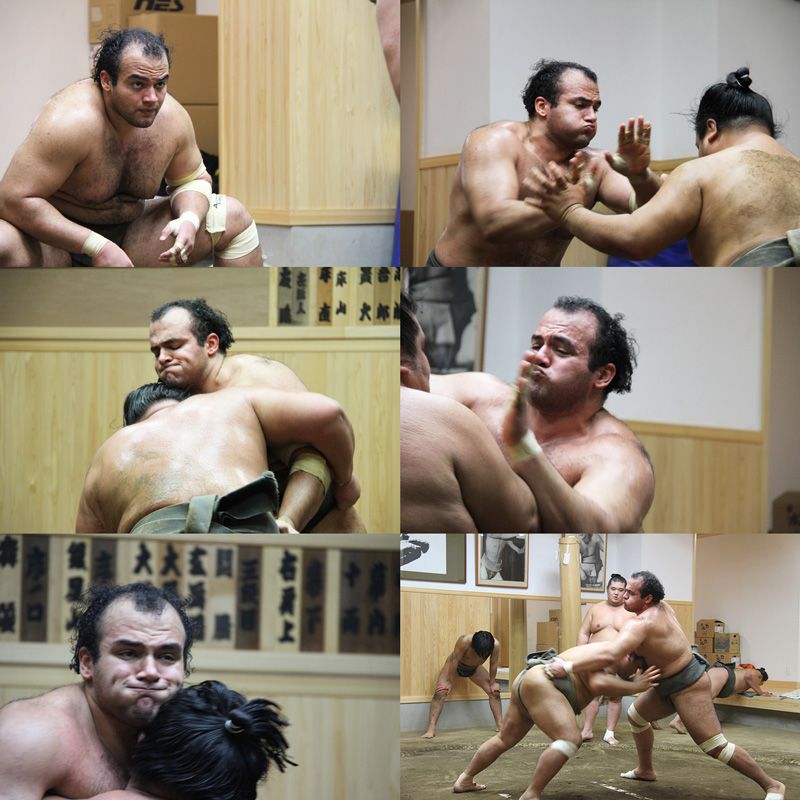

A scene of "sanbangeiko" (repeated practice bouts).

A scene of "sanbangeiko" (repeated practice bouts).

INTERVIEWER Do you feel any pressure, as the first rikishi to come from Africa or the Middle East?

ŌSUNAARASHI As the only one, of course there’s tremendous pressure. At the same time, because of this pressure, I feel I have to do my utmost—and this really motivates me. I’d like people all over the world to have a better understanding of sumō. People from the Middle East are unjustly seen as trouble-makers, but I want to show that we can play a regular part in any profession.

INTERVIEWER Twenty-four wins, three defeats, and one default due to injury; your record so far [as of the conclusion of the November 2012 tournament] is fantastic. Do you feel you’ve made progress?

The strict but warm-hearted stable master, Ōtake, offers some advice.

The strict but warm-hearted stable master, Ōtake, offers some advice.

ŌSUNAARASHI What’s important for me isn’t how many times I win, but how many times I lose. I’m always asking myself: “Why did I lose that bout?”

Anyway, I have to keep working hard to get to be a yokozuna [Grand Champion—the highest rank]. I’ve never once thought “I give up.” But I have felt totally exhausted any number of times! [Laughs]

INTERVIEWER What do you think about the strict relations between senior and junior rikishi in each sumō stable?

ŌSUNAARASHI It was a tremendous shock. In Egypt I was a champion and treated like a king. But here everyone treats me like a slave. [Laughs] But to make my dream come true, I just have to accept that treatment and be patient.

Hopes to Be Judged for His Skills and Character

INTERVIEWER What do you think of Japanese food?

ŌSUNAARASHI As long as a dish doesn't contain pork, I have no problem. My oyakata and the people who do the cooking understand about my religion, so I don’t have to worry about it. They make a point of keeping pork out of my meals.

Former sumō wrestler Yuho is in charge of preparing meals at the Ōtake stable (left). "Chanko" is the general term denoting the food prepared by sumō wrestlers. Ōsunaarahi’s favorite is "chanko-nabe" with chicken.

Former sumō wrestler Yuho is in charge of preparing meals at the Ōtake stable (left). "Chanko" is the general term denoting the food prepared by sumō wrestlers. Ōsunaarahi’s favorite is "chanko-nabe" with chicken.

“Chanko-nabe” is a kind of stew, traditionally the main dish eaten by the wrestlers. At Ōtake stable it is made with stock taken from chicken bones, according to the traditional recipe that Ōtake “oyakata” received from his own stable master, Taihō.

“Chanko-nabe” is a kind of stew, traditionally the main dish eaten by the wrestlers. At Ōtake stable it is made with stock taken from chicken bones, according to the traditional recipe that Ōtake “oyakata” received from his own stable master, Taihō.

Ōsunaarahi plays around with a young sumō fan.

Ōsunaarahi plays around with a young sumō fan.

INTERVIEWER How do you deal with Ramadan?

ŌSUNAARASHI Ramadan is no problem. But the humid summer heat is hard to bear. I fell ill because of it.

INTERVIEWER Do you feel self-conscious walking in the street dressed in a yukata summer kimono?

ŌSUNAARASHI Not at all. In fact, I feel quite proud, because people think: “Look, a sumō wrestler! How cool.” There are even some people who didn’t know much about sumō before but have become interested because of me. So I walk around in my yukata, proud to be a rikishi.

INTERVIEWER What are the things that you admire about Japan and what are you critical about?

The Ōtake stable master, who oversees Ōsunaarashi’s training: “Succeeding in the sumō world takes more than strength. Whether Japanese or foreign, sumō wrestlers are expected to be willing to learn about Japanese culture and to behave with decorum. It is important for the people around Ōsunaarashi to see that he’s giving it his all and that he has a sense of humility. We have an expression, ‘Begin with a bow and end with a bow,’ and I want Ōsunaarashi to learn the spirit behind this saying.”

The Ōtake stable master, who oversees Ōsunaarashi’s training: “Succeeding in the sumō world takes more than strength. Whether Japanese or foreign, sumō wrestlers are expected to be willing to learn about Japanese culture and to behave with decorum. It is important for the people around Ōsunaarashi to see that he’s giving it his all and that he has a sense of humility. We have an expression, ‘Begin with a bow and end with a bow,’ and I want Ōsunaarashi to learn the spirit behind this saying.”

It’s really well organized, and everyone goes about their business systematically. The standard things that need to be done are done properly—people don’t go in for half measures. Middle Easterners quite often tend to lose interest in what they’re doing and give up half way. I’d like them to know about this good characteristic of Japanese people. On the other hand, sometimes life is made difficult in Japan because there are so many rules. Also, when I visit a trendy area like Shibuya—and see so many strange hairstyles and ways of dressing—I feel like I’ve stepped into the world of manga. I even see men who dye their hair, which takes some getting used to, because that is not considered a very manly thing to do in my part of the world. [Laughs]

INTERVIEWER What is your aim as a rikishi?

ŌSUNAARASHI I want to be judged on my ability as a rikishi, without any focus on nationality or religion or race. Above all, I want to become a yokozuna. If more people become fans of sumō because of the way I wrestle—rather than because I’m a Middle Easterner—that would also be satisfying. Relations between people have nothing to do with nationality or religion or skin color. I hope that my efforts will help to bring people in the Middle East and Japan closer together.

Note: Each sumō wrestler, known as a rikishi, belongs to a heya (“stable”). All the rikishi in a heya lead a communal life and train every day under the supervision of their stable master, known as the oyakata, who himself a retired rikishi. Anyone who passes the test to become a rikishi can join a heya. Some rikishi are as young as 15 years of age. Inside the heya there is a sumō ring for training.

Egypt Islam sumō Osunaarashi¬ Otake stable Yokozuna Arab sport ritual