Architecture and the Blueprint for Gender Equality: Interview with Venice Biennale Commissioner Ōta Kayoko

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Benefits of Being an Outsider

INTERVIEWER Were there any difficulties that came with being the first female commissioner of the Japanese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale?

ŌTA KAYOKO Not really. When it came to conducting research and raising the necessary funds I benefited from a lot of help, not only from those in the world of architecture but also from corporations and foundations. In fact, it seemed that people were even more willing to help me out as I was a woman. But looking at the national pavilions of other participating nations, it seems that we still have rather a long way to go in terms of female leadership.

INTERVIEWER How did you meet Rem Koolhaas,(*1) director of this year’s biennale?

ŌTA In 1988 he visited Japan for an exhibition of his work in Tokyo. At the time I was involved with some colleagues in publishing an alternative architectural magazine called Telescope, and right away we requested an interview with him, which was his first in Japan. That’s how I was able to meet him at a time when he was famous as the author of Delirious New York.

In 2002, quite a while after that first meeting, I was asked to curate a major retrospective of the work of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, the architecture firm that Koolhaas found, and its think-tank AMO at the New National Gallery in Berlin. That year, I moved to the Netherlands to begin what would be a ten-year stint working for AMO.

INTERVIEWER What kind of work were you doing before that?

ŌTA After graduating from university, I found a job working on international conferences and exhibitions under the direction of the architect Kurokawa Kishō. Although I had majored in international law, my interest in modern art and architecture led me to change course and aim for a job at an architectural firm. But since I hadn’t specialized in the study of architecture, I was an outsider then—and have been ever since. I’ve always had a slightly different perspective and outlook, and felt that this “outsider” sensibility would be of use. From the outset, I’ve stubbornly stuck to that sensibility. [Laughs]

Fewer Japanese Interns at OMA

INTERVIEWER The organization OMA is quite international, isn’t it?

ŌTA We have staff of an amazing range of nationalities, from every continent. We used to get a lot of Japanese interns coming to serve an apprenticeship at OMA, but unfortunately that’s much rarer nowadays. They’ve been replaced by Chinese and Koreans.

INTERVIEWER Are there many women working there?

ŌTA Yes, around 40% of the staff are women, and at OMA no distinction whatsoever is made between the sexes. But, looking at the architectural world as a whole, it caused a big stir in 2010 when the Venice Biennale chose its first female (and first Asian) director, Sejima Kazuyo. I think this shows that, even internationally, everything still revolves around men.

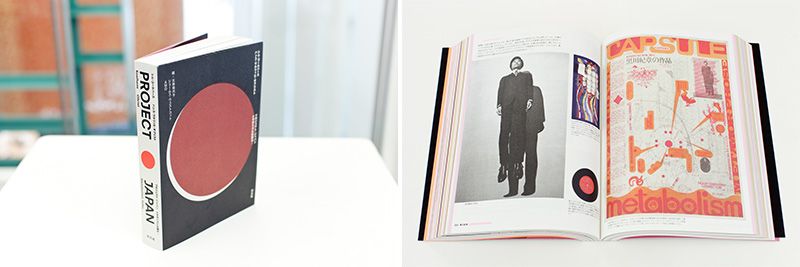

Ōta worked with Rem Koolhaas on the book Project Japan, which examines the postwar avant-garde architectural movement in Japan known as “Metabolism.”

Ōta worked with Rem Koolhaas on the book Project Japan, which examines the postwar avant-garde architectural movement in Japan known as “Metabolism.”

Looking Back on a Century of Modernization

INTERVIEWER What is the aim of the current exhibition?

ŌTA The Venice Architecture Biennale now has 66 national pavilions, along with two main venues overseen by the director. This year’s director, Koolhaas, invited the national pavilions to work together on a kind of global research project, and most of the participating nations agreed. The project, titled Absorbing Modernity 1914–2014, calls for each country to look back at its architecture over the past century to see how it has changed as a result of modernization, and also to understand what traditions and unique characteristics were lost during that time. It is the first project of its kind in the history of the Biennale, and I think it has been a huge success.

INTERVIEWER Why did the Japanese pavilion opt to focus on the architecture of the 1970s?

ŌTA In considering whether there was a particular period in which Japanese architecture reacted against the modernization taking place in the wider society, the 1970s stood out as a perfect example.

That was the decade when architects like Andō Tadao and Itō Toyoo, who are now globally renowned, prompted a root-and-branch rethink of architecture’s social significance as a profession. Those architects brought about radical initiatives and advocated fundamental change. In present-day Japan, though, you just can’t feel that kind of energy. Our hope was that the exhibition could energize today’s young people who are facing the challenges of contemporary society by conveying to them some of the developments from the 1970s.

It’s possible that the construction industry will see an upturn under the policies of Abenomics, much like it did during the “bubble” years. But that change won’t be of much use if it only takes place on the surface, without solving deeper issues. That’s why we want people to take another look at the 1970s, and at the revolts that took place during that decade thanks to young architects and historians. We hope that this can lead to a fundamental reconsideration of the relationship between society and architecture, including some self-criticism within the industry, and also for people to deeply consider what things are truly necessary.

Equality Is Not Just a Numbers Game

INTERVIEWER You just mentioned the term “Abenomics.” Another recently coined term is “womenomics.” How do you view the employment situation for Japanese women?

ŌTA The idea that something will change simply by increasing the number of women is simplistic. The task also involves undoing all of the long-established, ingrained values of large organizations, so it won’t be so simple. The United States has introduced affirmative action policies that establish quotas for the hiring of ethnic minorities, but that approach has also faced a lot of criticism. It’s much the same in Japan. That is, the issue is not just about increasing the number of women in management positions by a particular amount. The nature of the work must change, too. There’s a limit to what can be achieved by suddenly promoting a lot of women to the top jobs. Such changes need to be combined with a revolution in the value systems of organizations, or it won’t work.

INTERVIEWER How did you manage to gain such an international outlook?

ŌTA As a high school student, I spent some time in America as an exchange student. I experienced how speaking two languages leads to changes, not just in the way you think but even in your very sense of self. At first, I felt a conflict arising from the distance between my Japanese-speaking self and my English-speaking one. But gradually, almost at a subconscious level, I began to adjust and feel as though I could find a way to bridge the gap in culture and values. That ability to achieve a balance by seeing things from multiple perspectives is what people probably mean when they talk about an “international outlook.”

Even though OMA is based in the Netherlands, the lingua franca is English. I remember how, one day, after seven years with the organization, Koolhaas suddenly told me that my English had improved. I hadn’t noticed it myself, but it coincided with a period when I was finally beginning to feel confident that I could get my point across and argue logically with Westerners. It was around that same time that I suddenly began to appreciate the unique qualities of Japan.

(*1) ^ Rem Koolhaas (1944–) is a Dutch architect and urban planner with a host of awards to his name, including the Pritzker Prize (2000), the Praemium Imperiale (2003), and the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 2010 Venice Biennale of Architecture. Head of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), an architectural firm with offices in cities including Rotterdam, New York, Beijing, Hong Kong and Doha, as well as its own architectural think tank, AMO. Originally a journalist, Koolhaas is noted for his unique approach to research into the role of urbanism and architecture, based on thorough factual analysis. His first book, Delirious New York (1978), is regarded as one of the essential works on modern urbanism and architecture. As director of the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, Koolhaas proposed a research project entitled Absorbing Modernity 1914–2014, in which participating nations are invited to look back on their own history as a way of finding a new way forward in restoring the essential richness of architecture worldwide.

Getting Your Point Across

INTERVIEWER What do you think about the way Japan presents itself overseas?

ŌTA If I may continue to draw upon OMA, it is an organization where very able individuals from all over the world gather to hone their skills by competing against each other. After spending a long time in such an environment, you start to see the unique aspects of the Japanese approach to communication and presentations. Of course, there are a lot of good aspects of that approach, but the extreme meticulousness and cautiousness you often see in Japan can be a barrier. Despite the knowhow and aesthetic sensibilities that many Japanese people have, and the wealth of information available, those things are not always effectively conveyed to other people. There’s a tendency in Japan to focus too much attention on superficial details without expressing the more fundamental aspects of something. So time runs out before the key point has been explained. You might say that this detail-oriented approach has made it hard to fully convey the big picture.

ŌTA If I may continue to draw upon OMA, it is an organization where very able individuals from all over the world gather to hone their skills by competing against each other. After spending a long time in such an environment, you start to see the unique aspects of the Japanese approach to communication and presentations. Of course, there are a lot of good aspects of that approach, but the extreme meticulousness and cautiousness you often see in Japan can be a barrier. Despite the knowhow and aesthetic sensibilities that many Japanese people have, and the wealth of information available, those things are not always effectively conveyed to other people. There’s a tendency in Japan to focus too much attention on superficial details without expressing the more fundamental aspects of something. So time runs out before the key point has been explained. You might say that this detail-oriented approach has made it hard to fully convey the big picture.

The downside of meticulousness is the tendency to stick to established protocols and overlook essential points. But if people in Japan could be more accepting of new approaches, without sacrificing their attention to detail and aesthetic sense, then I think that the results could be quite interesting.

A Genuine International Outlook

INTERVIEWER We hear a lot in Japan about “internationalization,” but it seems that the reality has yet to catch up to the rhetoric.

ŌTA It’s still difficult for foreigners to be fully absorbed into Japanese society. By the time of the 2020 Olympics, I’m sure we’ll see some change in Tokyo, due to the establishment of special zones in which global businesses are being encouraged to set up their Asian headquarters. But simply fixating on the Olympics as a goal is typical of the kind of mistakes that Japan has consistently repeated throughout its history. We need to do away with this flimsy notion of superficial internationalization and enact more fundamental changes. That’s going to take tolerance, patience, and overall changes in values, but without those things we won’t see a more international society in Japan and Japan’s cities will not be able to outperform their rivals in the rest of Asia.

INTERVIEWER Isn’t that an area where more and more women might be needed?

ŌTA There’s no doubt that female personnel constitute a very valuable and necessary force. Women have a number of hidden strengths. Along with being adept at coming up with the kind of intuitive and imaginative thinking that can be difficult to express with words, they also have an uncanny ability to make connections.

The Power to Transform Yourself

INTERVIEWER Do you intend to remain based in Japan for a while?

INTERVIEWER Do you intend to remain based in Japan for a while?

ŌTA Yes, I think Asia is the most exciting place to be right now. Even though there are a lot of issues regarding Tokyo as an international hub, it seems to have a lot of fresh potential. By now I’m used to my role as a perpetual outsider, moving from place to place, but I do feel that I’d like to work in Asia, drawing on all my past experience.

INTERVIEWER Finally, do you have a message for the women of Japan?

ŌTA I want to say that our own concept of ourselves is something to be updated every single day. I think most people have a very fixed idea of what type of person they are, but in fact, far from being set in stone, any of us can change—to an unimaginable degree. We should all stop saying “it’s because I’m a woman,” and make an effort to look at ourselves from a different angle and try new things. It’s OK to be selfish, and we should set goals that we stick to with real grit. This is actually what is demanded of us in the current climate, so we shouldn’t be afraid to stand up, express ourselves, and even clash with others when necessary.

What you don’t say won’t get heard, and in that way nothing happens. Changing our outlook to expand our own horizons is the first step toward changing society. These are all things that I also need to remind myself of sometimes.

Venice Biennale

The Venice Biennale, which began in 1895, is a major biannual exhibition of contemporary art held in odd-numbered years from June to November. The delegations of participating nations select a commissioner as well as artists, whose work is exhibited in one of the many permanent “national pavilions” scattered around the Giardini, a park in the east end of the Venice island that serves as the festival site. Countries not allocated a permanent pavilion set up their own exhibition spaces elsewhere in the city. The first Japanese delegation participated in 1952, and the permanent Japanese Pavilion, designed by Yoshizaka Takamasa, was completed in 1956.

The Venice Architecture Biennale began in 1980, following the same format as the art biennale, but was initially held on an irregular basis in even-numbered years. The 2014 exhibition, the fourteenth such event, is directed by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, who was responsible for planning and defining the theme, “Fundamentals.” Ōta Kayoko was appointed the first female commissioner of the Japanese Pavilion, whose 2014 exhibition is titled In the Real World. The “Golden Lion” prize is bestowed on the top exhibit in each award category. The 2014 prize for architecture was awarded for the first time to the South Korean Pavilion. Past Japanese winners of the “Golden Lion” include the 1966 exhibit of the painter Ikeda Masuo and the 2012 exhibit led by Itō Toyoo titled Architecture in the Wake of Disaster, a response to the earthquake and tsunami of the previous year. Other winners of the award include the musician and artist Ono Yōko, who received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement in 2009.

2014 Venice Architecture Biennale

June 7 to November 23, 2014

http://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/

(Based on an interview conducted on July 17, 2014, by Yata Vattani Yumiko. Photographs by Igarashi Kazuharu.)