A Nighttime Banana’s Insights into Disability: Nonfiction Author Watanabe Kazufumi

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Telling It like It Is

Shikano Yasuaki passed away in 2002 at the age of 42 after suffering for most of his life from muscular dystrophy. The new film, Konna yofuke ni banana kayo (A Banana? At This Time of Night?), offers a good introduction to his story. Shikano, who led a defiantly “independent” life with the help of many volunteers in Sapporo, is played by fellow Hokkaidō native Ōizumi Yō. Full of humorous and touching moments, the film questions prevailing assumptions about caring for people with disabilities.

Konna yofuke ni banana kayo (A Banana? At This Time of Night?), starring, from left, Takahata Mitsuki, Ōizumi Yō, and Miura Haruma, was released in Japan on December 28, 2018. (© 2018 A Banana? At This Time of Night? Film Partners)

The original nonfiction book, however, is a far more complex human drama, delving deep inside the psyches of people with disabilities and their caregivers. Written by Watanabe Kazufumi over a period of two-and-a-half years based on interviews and personal engagement with Shikano, it highlights the often tense relationship between Shikano—portrayed as domineering and self-centered—and the young volunteers who look after him. The book, which unflinchingly examines both the light and dark aspects of caring for the disabled, received the Kōdansha Nonfiction Award and the Ōya Sōichi Nonfiction Award.

An “Independent” Lifestyle

The title of the book and film refers to a remark muttered by an exasperated student volunteer upon being awakened in the middle of the night to fulfill Shikano’s desire to be served a banana. The caregiver’s initial annoyance slowly gives way to respect over the commanding authority with which Shikano makes unrelenting demands on his helpers.

“Before I started writing this book, I didn’t really have an interest in physical disabilities or other welfare issues,” concedes Watanabe. He had been producing local government newsletters and other publicity materials on a freelance basis. There were no particular stories he wanted to tell, and he was unsure as to whether he should continue pursuing a writing career. It was then that he was asked by a fellow editor if he would be interested in writing a piece about Shikano Yasuaki. Looking over the dozens of notebooks that volunteers had filled with caregiving memos and comments, Watanabe was drawn by their extraordinarily rich emotional content. Why, he wondered, do these volunteers stay on to assist a man who is so abusive and self-centered? And can one really claim to lead an “independent” lifestyle when it is premised on round-the-clock care provided by others? In 2000 Watanabe began interviewing Shikano and his volunteer helpers for answers to these questions.

Shikano started using a wheelchair at the age of 18. Five years later, in 1983, he decided to leave the facility where he was housed and begin living “independently.” This was before the advent of in-home disability care and other welfare service support systems, so Shikano relied on volunteers—mostly students—that he himself recruited and trained to look after his needs. Living on a tightrope, he spent approximately the next 20 years being looked after by some 500 volunteers.

In writing about Shikano, Watanabe interviewed dozens of volunteers, sometimes jumping in to lend a caregiving hand himself. The interviewees had different reasons for staying, but they seemed to share a sense of something missing from their lives and stumbled on Shikano during their search. Some told him about their problems, and he comforted them and exhorted them to live more positively, so that it became unclear who was helping whom.

Shikano had an immense impact on countless young volunteers. Like the one who returned to medical school to become a physician, many have gone on to pursue careers in welfare, healthcare, or education.

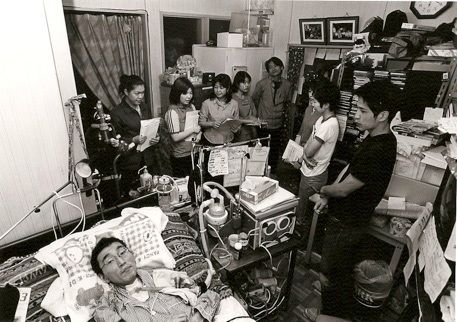

Shikano connected to a mechanical ventilator following a tracheotomy operation in 1995. (© Takahashi Masayuki)

The View from Hokkaidō

Watanabe won accolades for Banana but did not publish his second book until eight years later. Kita no mujin’eki kara (The Unstaffed Train Stations of Hokkaidō), too, was a critical success, winning such awards as the Suntory Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities and the Ishibashi Tanzan Memorial Journalism Award. His “second maiden work,” as Watanabe calls it, takes the reader on an eye-opening journey through the harsh realities of community life in Japan’s northernmost prefecture, using seven active train stations that do not have any attendants as gateways to the many critical issues confronting rural Japan today: the state of primary industries, environmental protection, tourism, depopulation, “marginal” villages (where over 50% of the population is 65 or older), consolidation of municipalities, and local government.

Kayanuma Station, adjacent to Kushiro Marsh National Park, is known for its support for the local red-crowned crane population. Through interviews with local residents, Kita no mujin’eki kara (The Unstaffed Train Stations of Hokkaidō) explores the complex issues surrounding the protection of endangered species. (© PIXTA)

Watanabe was born in Nagoya and spent his middle and high school years in Osaka. He became infatuated with Hokkaidō, though, after watching the TV series Kita no kuni kara (From the Northern Country), and the film Eki (Station), starring Takakura Ken—both of which were set in the prefecture. After studying at Hokkaidō University, he has maintained his base of operations in Hokkaidō over the past 30-plus years.

He chose to study to be a veterinarian at Hokkaidō University due to the influence of the zoologist, essayist, and filmmaker Hata Masanori, who was based in the prefecture. “I spent all my time editing a campus magazine, though, and hardly attended class. I eventually dropped out of college.”

Watanabe was also drawn to Hokkaidō’s natural beauty. “As soon as I entered college, I got a motorcycle license and traveled all around the prefecture. Biking around Hokkaidō was a big fad at the time, and I jumped right in.” He was among what became known as the mitsubachi-zoku, or “honeybee tribe”—local and out-of-town bikers who buzzed around Hokkaidō during the summer months in the 1980s and 1990s. To save on hotel expenses, he often curled up in a sleeping bag at unstaffed train stations scattered around the countryside.

After finishing Banana, his writing focus turned to these stations in Hokkaidō. His choice of publisher for his second book was not a Tokyo press but a local company—Hokkaidō Shimbun Press—which also published his first work.

“When I became a full-time writer in my twenties, I wrestled with the idea of moving to Tokyo,” Watanabe recounts. “Even after I gained recognition for my first book, people would tell me that I needed to be based in Tokyo if I wanted to do ‘serious work.’ I’m sure they meant well, and I could see their point, but I concluded that there was no need to be in the capital in order to write nonfiction. The problems Japan was facing or would soon face were far more visible and serious in rural areas. They appear in much sharper relief here, even if they don’t get much airtime on the national evening news.”

Breaking Down Preconceptions

His latest book, Naze hito to hito wa sasaeau no ka (Why Do People Support Each Other?), published in December 2018, revisits the issues of disability and welfare covered 15 years ago in Banana. Watanabe painstakingly conducted research and interviews over a five-year-period for his latest work, often prompting people to ask why it took him so long to “write just one book.”

In 2016, a mass stabbing took place at the Yamayuri-en care center for the disabled in the city of Sagamihara, Kanagawa. Uematsu Satoshi, a former employee at the facility, killed 19 and injured 27 others in what became one of the most horrifying crimes in Japan’s modern history. Following his arrest, the culprit is reported to have said that he hoped all disabled people would disappear. Such a sentiment, Watanabe posits in the book, lurks in the hearts of many people.

Indeed, social media is full of caustic, spiteful comments to the effect that people with disabilities are not worth keeping alive or that taxes should not be raised to support the disabled and the elderly.

“These comments miss the point that people who require care are not just on the receiving end of assistance,” Watanabe points out. “They reciprocate the attention they receive in ways that can be very beneficial for society. I, for one, would not be where I am today were it not for the time I spent with Shikano. And countless others have been a tremendous help to their caregivers.”

Nursing students receive caregiving training from Shikano. Watanabe is shown standing fifth from left. (© Takahashi Masayuki)

What was Shikano like in person? “He was very clear about wanting to create a society where people with even grave disabilities could lead normal lives at home. His idea of an ‘independent’ lifestyle, though, was quite different from notions we normally associate with that term.”

“When most people use the word, they mean being able to perform everyday tasks on one’s own, without the aid of others. But he turned this idea upside down; for him, it meant being free to decide how he lived his life. And he found it perfectly consistent to solicit the aid of others if that was required to achieve his goal.”

In Japan, there is a deep-seated aversion to inconveniencing others. As a result, Watanabe feels, many do not share their anxieties and pain or reach out to others for help. Feeling they need to be independent, people, instead, grow increasingly isolated from one another.

“Shikano’s approach was completely different, and on the surface, he may have appeared selfish and domineering. But his thinking and lifestyle have had a tremendous impact on many people. He was a pioneer who encouraged others with disabilities to leave their welfare facilities and move out into the community. In response, we now see a fuller range of in-home disability care services, and train stations increasingly have elevators and other accessibility features. I’m sure that as young people age, more will be grateful for the advances being made to build disability-friendly cities.”

Shikano’s Gift

For a full-time writer, having authored only three books over a span of 15 years may seem like an excruciatingly slow pace. But building trust with one’s interviewees is a time-consuming process. Watanabe pays for most expenses out of his own pocket, and he still needs to take on various freelance jobs to make ends meet. And while he frequently visits Tokyo for writing jobs, his base of operations remains in Hokkaidō.

“I’d love to do another book like The Unstaffed Train Stations of Hokkaidō, where I’m forced to grapple with issues threatening the outlying regions,” Watanabe says. “I’m also keeping an eye on the trial of the Sagamihara killer that’s about to start soon. I’ll probably be looking at welfare, healthcare, and nursing care issues all my life.”

Watanabe is no longer unsure about his career and is now teeming with ideas on new writing topics. This transformation may have been the greatest gift he received from Shikano Yasuaki.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 26, 2018. Interview and text by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Photos by Hashino Yukinori unless otherwise noted. Banner photo: Nonfiction author Watanabe Kazufumi during his November 2018 visit to Tokyo.)