The Kitchen at the End of the World: A Japanese Chef’s Adventures in Antarctica

Society Environment Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

If you live in Japan and frequent convenience stores, you may have seen Lawson’s akuma no onigiri, or “devil’s rice balls,” one of the chain’s more popular snacks. But you might not be aware of its remote origins. This tasty mixture of rice, edible green algae, and crunchy tenkasu (bits of fried tempura batter) actually originated in Antarctica. Chef Watanuki Junko developed it as an evening snack when she was cooking for the 57th Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition. Back home in Japan, she introduced it to TV viewers, and word spread through social media. Eventually, Lawson’s decided to market it.

Watanuki Junko was 41 years old when, after three applications, she was finally selected to join the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition (December 2015 to March 2017). What possessed her to submit to months of study, training, and preparation with the goal of spending more than a year in the frozen wastes of Antarctica?

“It’s Now or Never”

The seed of the idea came from a 2003 newspaper photo of Asahi Shimbun reporter Nakayama Yumi, the first female reporter to accompany the JARE wintering team. “That picture of a woman standing tall in her bright red parka against the pure white landscape left such an impression on me,” recalls Watanuki. But it was not until several years later that the seed sprouted into an ambition. In 2009, Watanuki saw the film Nankyoku ryōrinin (Chef of the South Pole), depicting the daily life of the wintering team at Dome Fuji Station deep in the Antarctic interior. For the first time, Watanuki felt she knew what she wanted out of life.

“I had graduated from culinary school and spent years in the food industry, yet I didn’t have a clear idea of the kind of culinary professional I wanted to be. When I saw the movie, it all fell into place. I finally understood that I didn’t want to be one of those chefs in a Michelin-starred restaurant who works only with the finest ingredients. I realized I would be much happier working in a community of sorts, where there’s an ongoing relationship between the chef and the diners.”

At the same time, Watanuki was looking for something a bit more adventurous than a school cafeteria. “When I saw the movie about the chef at the South Pole, I immediately thought, ‘That’s the kind of thing I want to do.’ I was tremendously drawn to the idea of working in Antarctica and cooking for the people who conduct research there.”

The Right Stuff

It took another five years for Watanuki to realize that ambition. During that time, she talked to former expedition team members and read up about the Antarctic. When her son entered high school, she decided it was time to act. “I thought, It’s now or never. If I waited any longer, my parents might get to the point where they needed my care, and I’d never be able to go.“

Each year, the National Institute of Polar Research accepts applications from members of the general public to participate in the Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition. The first time she applied, Watanuki was rejected without an interview. On her next try, she was eliminated after her interview. In January 2015, she tried again. This time, she passed the initial screening and interview and was notified that she was in. “Still, until I got the letter of appointment from the Ministry of Education, I was technically just a candidate. So I passed the next six months in a state of suspense.”

As Watanuki embarked on preparations for the expedition—including two types of training course (for wintering and non-wintering team members) and a series of physical exams—it dawned on her husband and son that she really intended to go through with this crazy scheme. Once they realized how serious she was, they gracefully gave her their blessing for a 16-month leave of absence. On the morning of her departure, as her son was leaving for school, he spread his arms wide and gave her a long hug.

Shōwa (also spelled Syōwa) Station, Japan’s main Antarctic research base, is located on East Ongul Island, four kilometers off the coast of the Antarctic land mass, some 14,000 kilometers from Tokyo. The climate is brutal, with temperatures falling as low as –45℃ in the winter. The Japanese research teams that have been stationed there since 1957 were all male until 1987, when a woman was finally permitted to join the 29th expedition’s summer team (popularly known as the “day trippers” because true night never falls on the group during their stay). It was another decade (the 39th expedition, 1997–99) before women were allowed to join the wintering team. Nowadays, around 10 women participate in JARE each year, although the number on the wintering team fluctuates considerably.

The wintering team of the 57th expedition, consisting of 30 members altogether (a team leader, 12 researchers, and a support staff of 17), included five women: a medical officer, a general administrator, a meteorological officer, a whole-earth monitoring officer, and chef Watanuki. The culinary team also included one male chef specializing in French cuisine—Watanuki’s specialty is Japanese.

To the Land of the Midnight Sun

Getting to Shōwa Station is an ordeal in itself. The expedition team first flew from Tokyo to Fremantle in Western Australia. There the members boarded the icebreaker Shirase, operated by the Maritime Self-Defense Force. Altogether, there were about 250 people onboard, including MSDF personnel. The voyage out took almost three weeks. (It takes at least twice as long on the way back). After battling seasickness on rough Antarctic seas, they were transported to Shōwa Station by helicopter. “All told, we spent more than two months of the 16-month expedition onboard the Shirase,” says Watanuki.

For the first two months, the wintering team, day trippers and MSDF personnel were all crowded into Shōwa Station. During that time, MSDF mess officers handled the meals, while the expedition team busied itself with unpacking and a variety of maintenance and construction tasks. “I was sore all over,” confesses Watanuki.

In February, all but the 30 members of the wintering team returned home, and the work of the cooking staff began in earnest.

The kitchen at Shōwa Station. The brutal Antarctic winds often shook the entire structure, causing the dishes to rattle in their steel cupboards.

Getting the Blues for Greens

One of the biggest handicaps facing the culinary staff on the wintering team is the lack of access to fresh food. The team has to bring along a whole year’s worth of cooking supplies. The process of planning and stocking up on about 2,000 different ingredients (weighing more than 30 tons altogether) begins four months prior to departure.

“As soon as we arrived at Shōwa Station, we formed a kind of bucket brigade to convey all that food into the freezers,” recalls Watanuki. “It took two full days.”

Managing the food supplies is an important aspect of the culinary team’s duties.

The team as a whole suffered from “green deprivation,” according to Watanuki. “There was a special room where we grew hydroponic vegetables, but it took at least three or four weeks for the plants to mature, and there was just no way to grow enough to feed everyone. Still, some people liked to go into that room while they were brushing their teeth or whatever to gaze on the green things growing there. The Antarctic landscape is just three colors: white, blue, and brown. I had no idea how much I would miss the color green.

Taking the “do yoga anywhere” mantra literally, Watanuki and her colleagues gave it a go under the Antarctic sky, only to find that the mats froze hard in a matter of minutes.

Seals were a common sight near the station’s coastal observation posts.

Cooking Up a Taste of Home

The kitchen at Shōwa Station offers a no-choice menu that changes daily. A certain number of dinner menus are planned around requests from the team members. “The most challenging request I received was for samgyetang [Korean chicken soup with sweet rice and ginseng]. I did have whole chickens to work with, but not all the medicinal herbs required. I improvised with the seasonings I had on hand, and everyone seemed to enjoy it a lot.”

In addition, the chefs planned special thematic meals geared to the Japanese and Antarctic seasons. For example, the expedition marked the advent of Japanese spring with a “cherry-blossom viewing” meal and the Antarctic winter solstice (in June) with a “midwinter festival.”

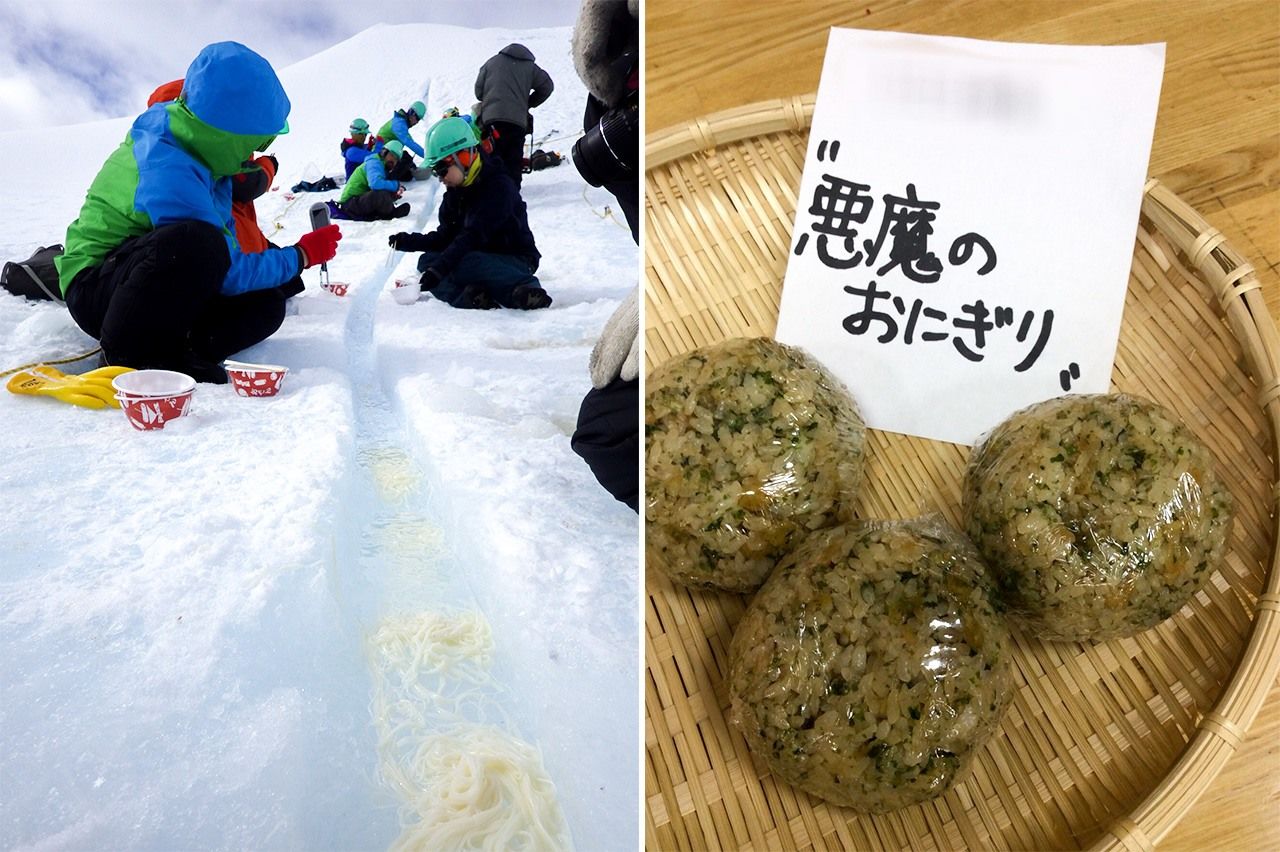

Watanuki also honored the tradition of capping off the expedition with an outdoor meal featuring a popular Japanese summer dish, nagashi sōmen—cold “flowing” noodles served in a flume. Ordinarily, diners sit in front of a bamboo chute and catch the fine noodles with their chopsticks as they flow past. In Antarctica, the chute is cut into an iceberg.

“The one thing the members are allowed to take home with them from Antarctica is ice,” Watanuki explains. “So, on a designated day, everyone goes out onto an iceberg with pickaxes to chip off some ice as a souvenir. That’s when they eat nagashi sōmen on the iceberg. I brought along some tempura, as well as hot water, boiled noodles, and dipping sauce.”

Iceberg nagashi sōmen, a Japanese Antarctic tradition (left); Akuma no onigiri, or “devil’s rice balls.”

Obliged to keep waste to an absolute minimum, Watanuki was at pains to make good use of any food left over from meal preparation. One of her favorite methods was to use leftover rice and other ingredients to form onigiri, or rice balls, that the staff could snack on after dinner. Along the way, she perfected her recipe for “devil’s rice balls”—so named by a team member who found the high-calorie snack too tempting to resist. They were especially appreciated by those assigned to nighttime snow-shoveling duty, one of whom called the rice balls “a mouthful of happiness” after a hard night’s work.

Riding the Snowcat

Watanuki had duties other than cooking, including construction in the summer and snow removal in the winter. At times she was called on to drive a truck or operate a forklift. But her favorite job of all was driving the snowcat, a large, enclosed, multi-passenger snow vehicle. Sometimes, when a small group needed to travel out to one of the observation posts situated on the mainland, Watanuki drove them out in the snowcat. After transporting the group and their supplies across the sea ice, she might prepare their meals in the observation hut or in the snowcat itself.

“Obviously, I’d never driven a snowcat before. You maneuver with two levers. The mechanism isn’t complicated, but you have to pull really hard to steer. It’s quite stressful and tiring to maneuver such a big heavy vehicle over the ice and snow. Sometimes I drove with the pain patches still plastered to my arms.”

Nonetheless, Watanuki developed the knack. On several occasions she transported team members all the way out to the depot and way station known as S16, a four-hour drive from Shōwa Station. Despite the physical and mental strain, she relished the opportunity to drive for hours through the vast, white expanse of the Antarctic.

Clearing the Air

About a month after the team’s arrival, Watanuki got into an altercation with a team member affectionately known as “Gramps.” One day, Gramps curtly informed Watanuki that he considered it a mistake to hire chefs for the wintering team. He let it be known that he resented having to arrive at the dining room at a predetermined time, arguing that his observation duties should take precedence. After trying unsuccessfully to reason with him, Watanuki was on the verge of tears. But the next day, Gramps apologized.

“He worked at an observation post that was a full twenty-minute walk from the dining room. Still, from that time on, he showed up religiously five minutes before mealtime. He was never late for a meal. I took that as a gesture of goodwill on his part.”

Having returned to Antarctica with the most recent expedition, Gramps sent Watanuki a New Year’s greeting card from Antarctica last January. It arrived in her mailbox in April. “The mail only leaves Shōwa Station once a year,” she explains.

Today, Watanuki thinks of Gramps and the rest of the team as a second family. “It was such an intense and stimulating year,” she says. “How many opportunities does someone in her forties have to stretch herself like that?”

The icebreaker Shirase approaches the Japanese research base on East Ongul Island against the dramatic backdrop of the Antarctic land mass.

Like living in space, a year in Antarctica can play havoc with the human constitution, and Watanuki struggled to re-adapt to life in Japan. “Part of it was that my circadian rhythm was off. But it was also hard to deal with the superabundance of food and the huge amount of waste.” Watanuki has yet to readjust to that aspect of Japanese society. “As I see it, there wouldn’t be much point in going all the way to the South Pole if I lost the perspective that I gained while I was there.”

Her next goal? To go back. “Shortly before I left Antarctica, I had one last chance to pilot the snowcat over the sea ice, and it made me so sad to think that I might never drive through that pure white landscape again,” she said. “I’m determined to go back there and see it one last time.” Watanuki’s Antarctic adventure is not over yet.

(Interview and original Japanese text by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. South Pole photos courtesy of Watanuki Junko. Banner photo: Watanuki Junko at Shōwa Station in July 2016.)