Satō Hatsumi and the Lost Girls of Kabukichō: A Decade of Selfless Service

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Nighttime Patrol

It is 9:00 on a Friday evening in late June, and Satō Hatsumi and her team have just set out on one of their weekend “patrols” of Kabukichō, the iconic nightlife and adult-entertainment district in Shinjuku, Tokyo. The 72-year-old Satō may look slightly out of place in the neon-illuminated streets of this “town that never sleeps,” but to many of Kabukichō’s denizens, “Sato-bā” (“Ma” Satō) is a familiar and respected figure. Her business card identifies her as the director of Ninshin SOS Shinjuku (*1), a local nonprofit that offers free counseling to girls and young women suffering from abuse or facing an unplanned pregnancy.

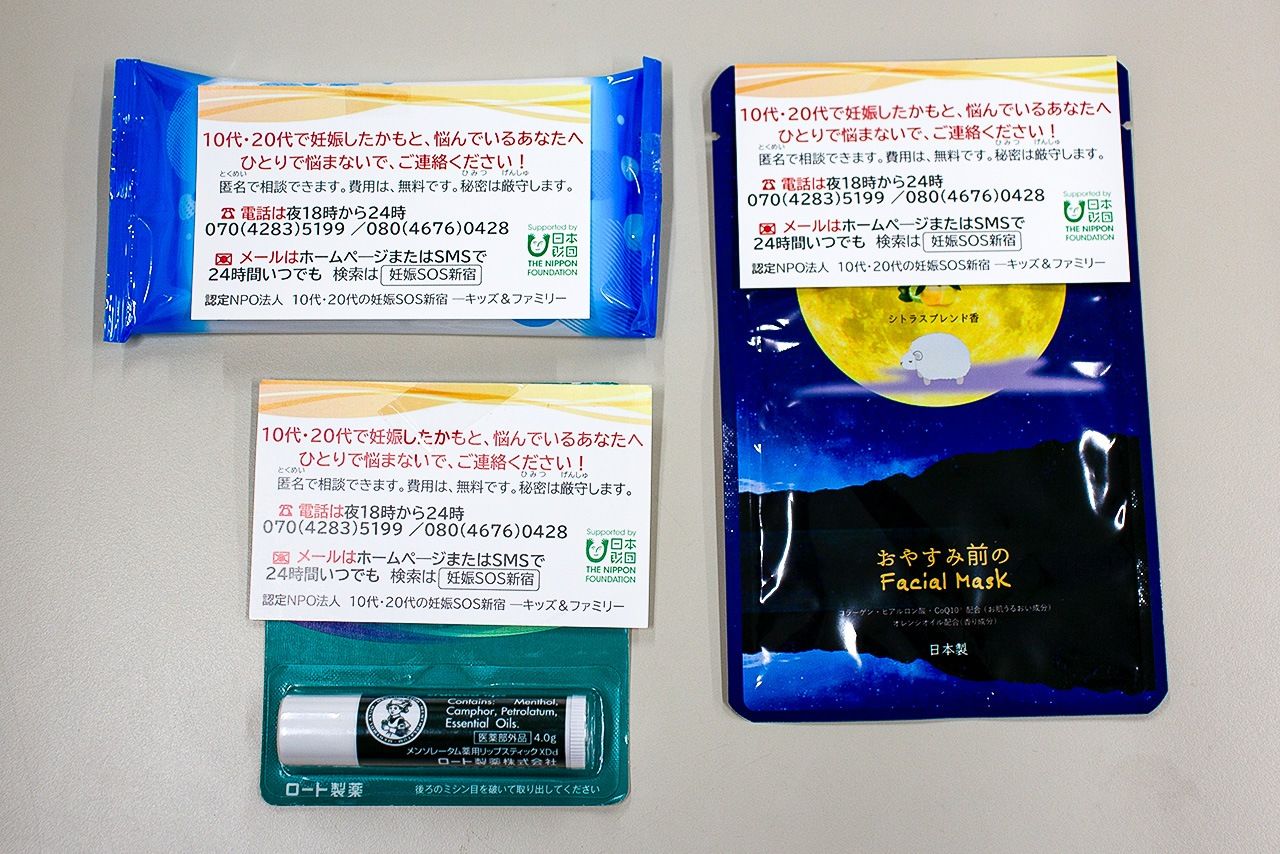

On their patrol, Satō and her team approach the girls seen soliciting customers in Ōkubo Park and outside the short-occupancy “love hotels” nearby. Satō offers them bags containing free lip balm, wet tissue, and facial masks, along with cards bearing contact information for the nonprofit’s counseling line. There is no pressure, no sales pitch. About half of the girls they approach accept the bags. “Hold onto the cards, okay?” says Satō. “And if you have any problems, feel free to get in touch.”

Satō stops for a moment to chat with a girl she knows and asks after a mutual acquaintance. “What’s your friend —— been up to lately? If you see her, will you tell her to get in touch with Sato-bā?”

Out on a weekend evening “patrol,” Satō Hatsumi offers swag bags to women and girls working the streets in the Kabukichō district of Shinjuku, Tokyo. (© Ninshin SOS Shinjuku)

Attached to the freebies are cards bearing the phone number and URL for Ninshin SOS’s free counseling service. (© Nippon.com)

On Friday and Saturday nights, the nonprofit’s social workers offer walk-in counseling in a room at the local community center. The space doubles as a lounge, a refuge where young women can retreat and refuel with snacks and instant noodles. The night counseling center serves as a model for the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Kimimamo youth counseling program, which debuted in Kabukichō.

Explosion of Host Bars

The sex industry has long been a conspicuous presence in Kabukichō. Over the past decade, the district has also become a magnet for runaways and other marginalized minors. (It was in 2019 that someone christened them “Tōyoko kids” after their preferred gathering spot beside the Shinjuku Tōhō Building, known for its towering Godzilla Head). But the proliferation of under-age sex workers in spots like Ōkubo Park is a more recent phenomenon. Satō believes the main catalyst was the post-pandemic proliferation of host clubs, establishments where women pay for male companionship.

Kabukichō’s Ichibangai street, June 2025. (© Nippon.com)

“Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 60 host clubs in Kabukichō,” says Satō. “By 2023, there were 330. The pandemic forced many of the district’s small bars and restaurants out of business, and rents fell sharply. Entrepreneurial types took advantage of the situation and opened a raft of new host clubs. That led to overheated competition, and many of the clubs responded by shifting their target from well-heeled mature women to teenage girls. At first they lured them in with low prices. Then they hiked their fees and encouraged their young customers to run up a tab. Many teenage girls have been forced into prostitution to pay off their debts.

“Over the past few months, some of these host clubs have begun closing down, but they’re being replaced by music clubs featuring menchika(*2) entertainers, and it’s basically the same game. The young male singers use sympathy and flattery to manipulate vulnerable girls and young women into relationships of dependency.”

Satō takes issue with media reports that have blamed the plight of under-age sex workers on their own “host crazy” behavior or depicted them as ordinary teenagers who took fandom a step too far. “Ninety percent of the girls who contact us for help grew up in abusive environments that denied them their personhood from an early age,” she says. “They’re traumatized by loneliness, and they come to Kabukichō feeling they have nothing to lose. When a young man approaches one of these girls with kind, caring words and begins to rely on her support, it touches her deeply. Girls who have somewhere else to turn will have the presence of mind to pull back before it’s too late.”

A backstreet on the east side of the Shinjuku Tōhō Building in Kabukichō, June 2025. The area has become a magnet for marginalized teens and the adults who prey on them. (© Nippon.com)

From Nursery School Teacher to Youth Counselor

For 34 years, beginning in 1975, Satō worked as a public nursery school teacher in Shinjuku. From the beginning she was acutely aware that some of her charges were victims of neglect or abuse, and she did all she could to help them. From 2001, she honed her expertise as a founding member of an organization established by Tokyo nursery school teachers and child welfare officers to study best practices in the detection of and response to child abuse (Hoiku to Gyakutai Taiō Jirei Kenkyūkai). Eight years later, she was offered a new opportunity to put that expertise to use.

“For years, I was convinced that being a childcare worker was my calling, and I would never work outside a nursery school,” she says. That changed in 2009, when Shinjuku, having decided to expand its support program for families with children from one center to three, tapped Satō to work as a counselor specializing in child abuse. Some of the families and children she worked with were dealing with serious mental health issues and developmental disabilities. But as soon as the child turned 18, their problems fell outside the scope of the Child Welfare Act. Satō felt deeply conflicted to see troubled young people age out of the program.

Cycle of Neglect and Abuse

Satō explains why young people who grow up in abusive or neglectful families often end up on the fringes of Japanese society.

“While they’re in nursery school,” she says, “the teachers can give them the attention they need, and at that age the kids communicate honestly with adults. But once they start elementary school, they fall behind. This is inevitable because their parents haven’t prepared them for grade school, and they don’t nurture good study habits. And elementary school teachers have too much on their plates to give them the extra attention they require. They’re thrown in at the deep end.

“The teacher writes on the board what the students need to bring to school the next day. Kids who can’t read and write [hiragana] yet are already lost at that point. Before long, their classmates are giving them funny looks. Even if they’re not bullied outright, they’re treated differently—not invited to birthday parties and so forth. That kind of thing is extremely painful to children. Their self-esteem suffers, and in the end they feel like they don’t belong anywhere, at home or at school. I’ve seen quite a few cases of neighborhood girls who’ve made their Kabukichō debut before they were out of elementary school.”

Grappling with Teen Pregnancy

In 2015, Satō stopped working for the city, and in 2016 she earned her qualifications as a certified social worker and a psychiatric social worker. That same year, she founded the local nonprofit she still directs. She felt the need to break free from the confines of the government bureaucracy and build an organization capable of responding to personal crises around the clock.

“Kids often tell me that the worst times for them, when they feel they can‘t go on anymore, occur late at night, when the rest of the family has gone to bed, and the house is quiet,” says Satō. “But as a civil servant, you can’t be there for them at those times. I felt that the city’s support apparatus was out of step with the kids’ circumstances. And I also felt that we weren’t addressing one of the biggest problems teenage girls struggle with—namely, pregnancy.” Satō’s answer was to set up a nonprofit counseling service for girls and women aged 11 through 24 facing unwanted or unplanned pregnancies.

Clients generally make initial contact with the nonprofit by phone or email. The counseling itself takes place in person, providing the client wishes to continue. She almost always does, since few people send out such an SOS unless they are in desperate need of help.

The organization’s basic policy is to put the client in a position to receive all the social and medical services available to her. Accordingly, the first step is to personally accompany her to the appropriate medical facility, welfare bureau, and national health insurance office and help her complete all the required paperwork. Women with no fixed abode and those lacking the resources to pay for obstetric care are also put in touch with the agencies in charge of public assistance and other services for the needy. In a pinch, women can find temporary refuge at a shelter that the nonprofit operates.

“The idea is to provide multiple points of contact and create as extensive a support network as possible for these women. It’s very important that they learn to open up with people close to them and accept their help.”

A decade after founding her nonprofit, Satō remains totally committed to the lost girls of Kabukichō.

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Ishii Masato of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Satō Hatsumi, center, and her team pack swag bags to distribute to young women working the streets of Kabukichō. © Nippon.com.)

(*1) ^ The full name of the organization is 10-dai 20-dai no Nishin SOS Shinjuku—Kizzu & Famirī (Teens and Twenties Pregnancy SOS Shinjuku—Kids and Family).—Ed.

(*2) ^ Menchika is an abbreviation of menzu chika aidoru, literally, “male underground idols.” The term refers to boy bands that have yet to achieve commercial success and do most of their performing in small clubs.—Ed.