Contemporary Culture Going Global

French Manga Fans Inspire the Work of Tsutsui Tetsuya

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Deep Ties with France

Tsutsui Tetsuya (Photo: Laurent Koffel)

Tsutsui Tetsuya (Photo: Laurent Koffel)

The thirteenth Japan Expo, held outside Paris in July 2012, brought together some of the greats of the Japanese manga world, including Hagio Moto and Urasawa Naoki. Another manga artist in attendance was Tsutsui Tetsuya, who stood out due to his youthful style.

It was Tsutsui’s third trip to France after his appearance at the Paris International Book Fair in 2007 and the Japan Expo in 2008. Prior to this year’s Paris Expo, Tsutsui went on a book-signing tour that took him to eight cities, from the Belgian capital of Brussels in the north to Marseilles in the south. He is the first Japanese manga artist to make such a tour, which gives some idea of how popular Tsutsui is in the French-speaking world.

Back in 2004, Tsutsui published his first manga in France, called Duds Hunt. The French-language edition was the world’s first printed version of the manga, which Tsutsui had released online two years earlier on his website.

Despite his 2002 magazine debut in the August 22 extra edition of Monthly Shōnen Jump, Tsutsui was still largely unknown in Japan at the time. This led him to self-publish his stories on his website. He explains: “My motivation was simply to get a reaction from readers—not because I was hoping to land a contract or make money.” Despite these intentions, the success of the online effort opened the door to the publication of his work by the major publishing firms Square Enix and Shueisha.

After his work Manhole (serialized in the magazine Young Gangan) came to an end in May 2006, Tsutsui returned to the web the following May, self-publishing The Collector on his website. But after the end of The Collector, he went through a long artistic lull. During that inactive period he visited France for the first time—also his first trip overseas. He recalls the impact of that memorable trip: “I was surprised by the fresh new questions readers and journalists in France asked me. And it was a pleasure to engage in in-depth discussions. The trip restored my desire to draw manga. So I really owe a debt of gratitude to France and the passionate readers there.”

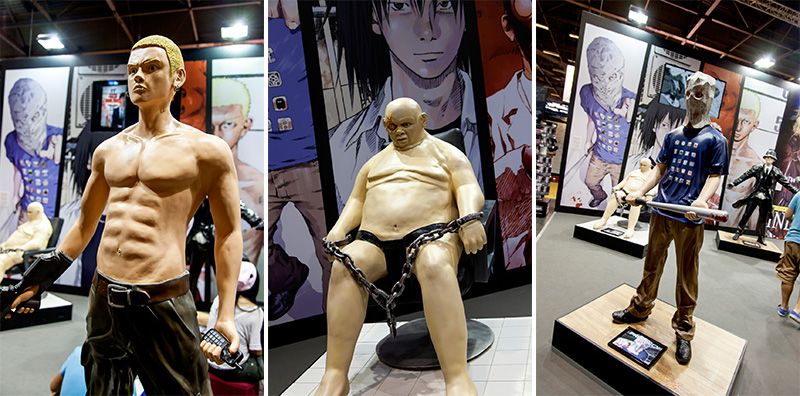

The life-size figurines of Tsutsui’s “manga” characters (from left to right): Nakanishi, the bad boy from “Duds Hunt”; Tamura, the helpless criminal in “Manhole”; and Paperboy, the antihero from “Prophecy.” (Photos: Laurent Koffel)

The life-size figurines of Tsutsui’s “manga” characters (from left to right): Nakanishi, the bad boy from “Duds Hunt”; Tamura, the helpless criminal in “Manhole”; and Paperboy, the antihero from “Prophecy.” (Photos: Laurent Koffel)

Questioning Social Attitudes

Tsutsui has now returned to form with his new manga series Yokoku han (Forewarned Crimes), currently serialized in the magazine Jump X published by Shūeisha. The first book-length volume of the manga was released in Japan on April 10, 2012, and just two and a half months later a French edition was published under the title Prophecy. That edition was released on June 28 by the French publishing house Ki-oon, just in time for the opening of the Japan Expo. The company, which has been backing Tsutsui for the past eight years, organized a large-scale promotion of his work at its Paris Expo booth.

Upon entering the Ki-oon booth right next to the entrance of the Paris Expo, visitors experienced the shock of encountering four life-sized figurines of Tsutsui’s manga characters. The figurines were arranged in a 30 square meter space in front of huge panels bearing images of his creations. Four artisans from the Luxembourg-based figurine company Tsume-art spent four months working intensely to produce the figurines.

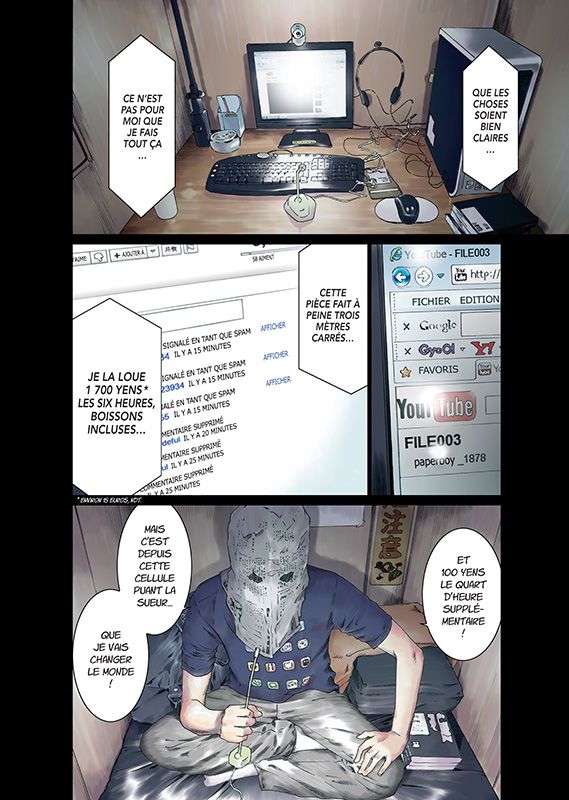

Right in the middle of the Ki-oon booth is the figurine of a man holding a baseball bat, his head covered by a newspaper; this is Paperboy, the aptly named antihero of Prophecy who releases video images on the Internet showing crimes about to be committed, and punishes evildoers. The character harshly punishes those who tread on the dignity of others. The manga deals with a theme treated in other works by Tsutsui, namely, the way in which people living on the margins of society use new technology to take the law into their own hands.

In his creative work, Tsutsui is highly concerned with the message he conveys to readers. The general trend these days is for magazine editors to “guide” young writers, but Tsutsui is an exception who dares to insist on his own viewpoint. “Japanese society is quite cruel to those who are different,” he explains. “It looks bad in Japan to have a gap in your resume, for instance, and if you have the misfortune to lose your job, you can find yourself left behind permanently. I hope that my Prophecy series will encourage readers to question whether this social attitude is normal or not.”

Scenes from the manga series “Prophecy” (© Tetsuya Tsutsui/Ki-oon)

Scenes from the manga series “Prophecy” (© Tetsuya Tsutsui/Ki-oon)

A Realistic Depiction of Cybercrime

Tsutsui’s ability to criticize society is directly linked to the praise he has won in France. Pop culture in France is often held together by a subversive attitude, as seen in the way hip hop has developed there in its own unique way. This may account for the popularity in France of Japanese manga artists like Mase Motorō and Arai Hideki.(*1)

On top of its social criticism, Prophecy has a very contemporary theme, concerning how the spread of social networks and the anonymity of the Internet gives rise to crime. In fact, Tsutsui came up with the scenario for the manga by scouring the Web for information on actual cybercrimes that have been committed.

It seems natural that adolescents and young manga fans would feel such an affinity for this series that revolves around issues related to their way of life. According to Médiamétrie, a French audience-measurement company, 77% of Internet users in France belong to a social networking service. As in Japan or the United States, France has also been subject to a constant increase in problems such as identity theft, moral harassment, and defamation. Readers have been drawn to Prophecy by this realistic aspect. Visitors to the Ki-oon booth at Japan Expo remarked on how closely the manga reflects what’s happening on the Internet now and that “some scenes include things that have happened to their friends.”

For French readers, Prophecy is not a manga set in faraway Japan. Rather, it is a story taking place right now in cyberspace—and this ability to dissect what is going on in present-day society is at the heart of Tsutsui’s importance as a manga artist.

(Abridged version of an article written in French in July 2012; photos by Laurent Koffel.)

Tsutsui Tetsuya and the Ki-oon staff dress up as the character Paperboy. © Ki-oon

Tsutsui Tetsuya and the Ki-oon staff dress up as the character Paperboy. © Ki-oon

(*1) ^ Mase Motorō, born in 1969, is best known for the manga Ikigami (Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit), serialized from 2005 until February 2012, first in the magazine Weekly Young Sunday and then in Big Comic Spirits (both published by Shōgakukan); a movie adaptation of the series was released in 2008. Arai Hideki, born in 1963, is the creator of manga that include Kīchi!! (Shōgakukan’s Big Comics Superior, 2001–6), Miyamoto kara kimi e (From Miyamoto to You; Kōdansha’s Weekly Morning, 1990–94), and Za wārudo izu main (The World Is Mine; Shōgakukan’s Weekly Young Sunday, 1997–2001).

manga Japan Expo France Paris social networking Tetsuya Tsutsui Mase Motorō Arai Hideki cybercrime