Contemporary Culture Going Global

Taniguchi Jirō’s World of Manga

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

When manga creator Taniguchi Jirō died in February 2017, the majority of the Japanese media described him as the artist of Kodoku no gurume (The Solitary Gourmet), the series he was best known for in his home nation. In France, however, detailed coverage in Le Monde and other press outlets primarily paid tribute to his solo works Aruku hito (trans. The Walking Man) and Haruka na machi e (trans. A Distant Neighborhood), which won acclaim in the country. Taniguchi may well be more highly regarded in Europe than he is in Japan. He took inspiration from Franco-Belgian comic artists like Mœbius and François Schuiten, and most of his works are available in French. His standing in France is apparent from his being one of just three mangaka to receive the Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, alongside Akira creator Ōtomo Katsuhiro and Matsumoto Leiji of Ginga tetsudō 999 (Galaxy Express 999) fame.

In December 2017, publisher Shōgakukan released two posthumous volumes including unfinished works by Taniguchi. An exhibition in the same month at the Maison Franco-Japonaise in Tokyo put his exceptional talent on display.

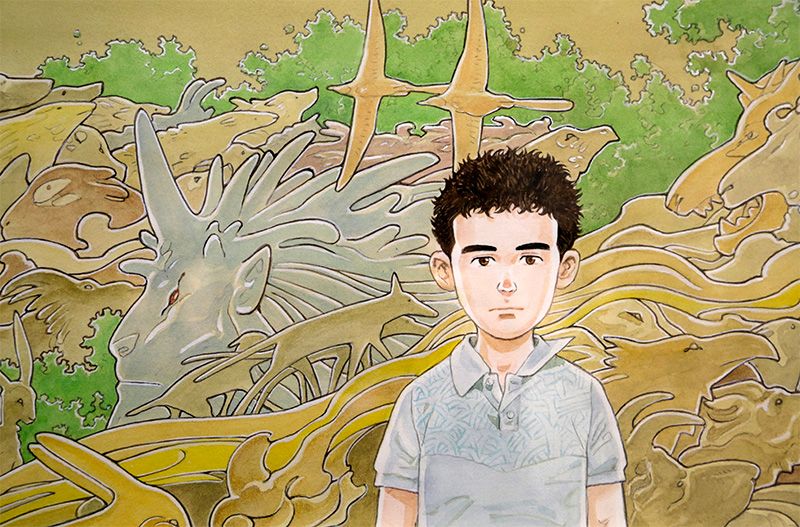

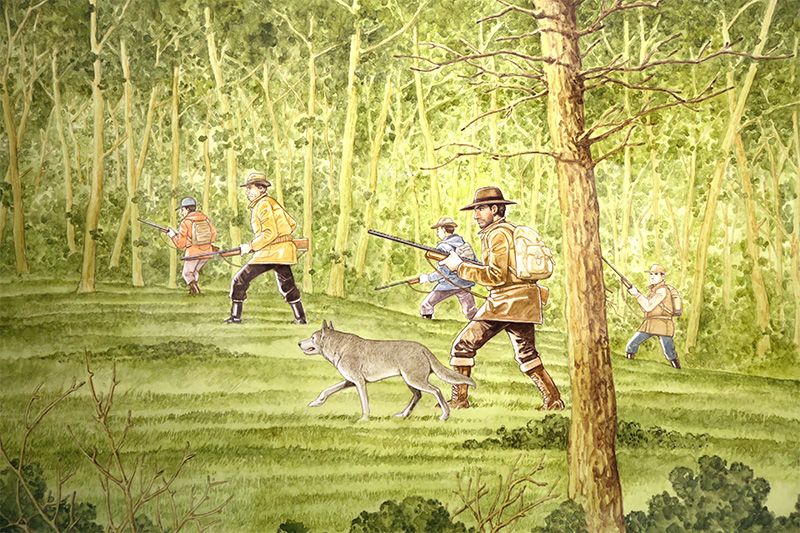

Taniguchi created Kōnen no mori (Light-Year Forest) in the last two years of his life, when he was battling illness. It was published in Japan in 2017 in an unusual full-color, landscape format. Taniguchi said that he wanted to create scenery that seemed to express its own emotions.

Taniguchi created Kōnen no mori (Light-Year Forest) in the last two years of his life, when he was battling illness. It was published in Japan in 2017 in an unusual full-color, landscape format. Taniguchi said that he wanted to create scenery that seemed to express its own emotions.

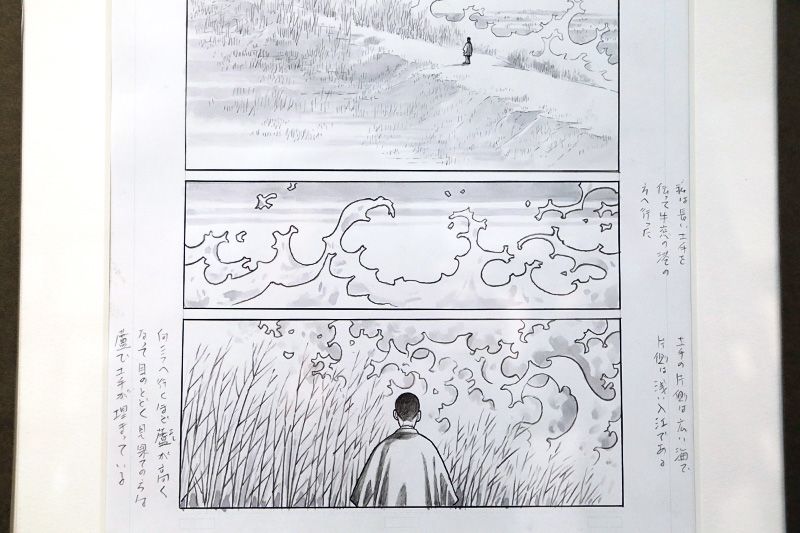

The collection Izanau mono (Tempting Things) includes works in science fiction, historical drama, modern, literary, and other genres, some of which are unfinished.

The collection Izanau mono (Tempting Things) includes works in science fiction, historical drama, modern, literary, and other genres, some of which are unfinished.

At Home in Different Genres

Born in Tottori Prefecture, Taniguchi made his debut in the 1970s in the Young Comic weekly. In the 1980s, he formed part of a new wave of creators working in a realistic comic style known as gekiga, collaborating with writers like Sekikawa Natsuo and Tsuchiya Garon (Marley Carib). The series Jiken’ya kagyō (Trouble Is My Business) continued until 1994, despite changes in magazine and publisher, with a noticeable evolution in Taniguchi’s style from the unpolished lines of the early days to later refinement.

Taniguchi’s early masterpiece Kaikei shuten was published as Hotel Harbour View in Canada in 1990. It was the first time foreign readers could encounter his art in translation.

Taniguchi’s early masterpiece Kaikei shuten was published as Hotel Harbour View in Canada in 1990. It was the first time foreign readers could encounter his art in translation.

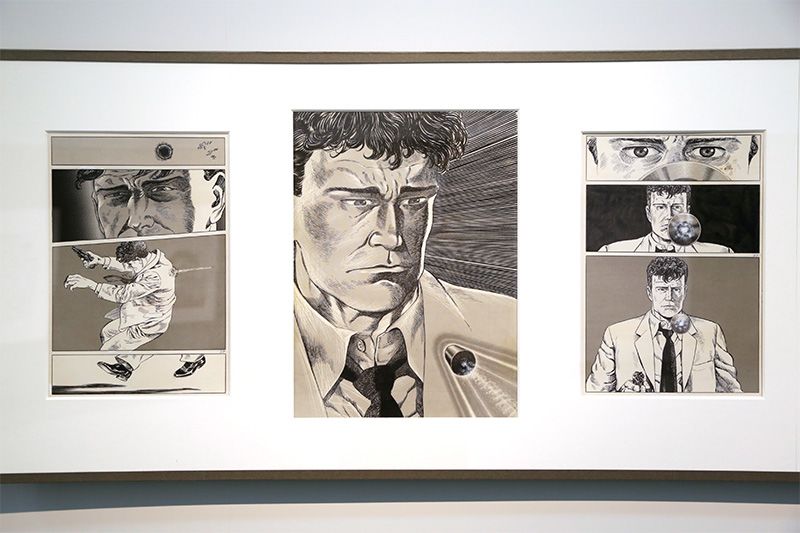

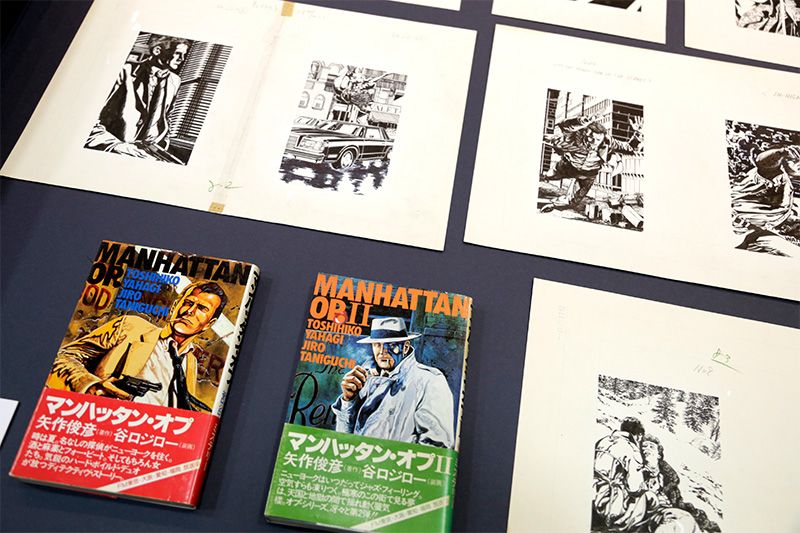

Taniguchi took inspiration from film noir in the illustrations for novelist Yahagi Toshihiko’s hard-boiled Manhattan Op.

Taniguchi took inspiration from film noir in the illustrations for novelist Yahagi Toshihiko’s hard-boiled Manhattan Op.

From the late 1980s to the 1990s, Taniguchi explored a range of new fields, working on the dog tale Buranka (Blanca), the mountaineering manga K, and Botchan no jidai (trans. The Times of Botchan). The latter work, which centered on Natsume Sōseki and other modern writers, won the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize. He also ventured into science fiction with Chikyū hyōkai jiki (Ice Age Chronicle of the Earth) and fantasy with Genjū jiten (Tales of the Prehistoric Animal Kingdom). It is rare to find a mangaka at home in so many different genres.

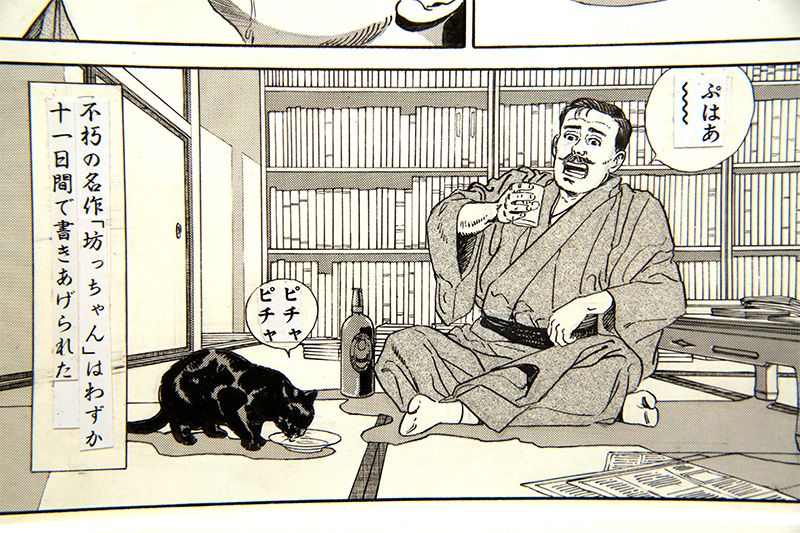

Botchan no jidai (trans. The Times of Botchan) took a decade to complete.

Botchan no jidai (trans. The Times of Botchan) took a decade to complete.

Kodoku no gurume (The Solitary Gourmet), illustrated by Taniguchi and written by Kusumi Masayuki, is the most popular work associated with Taniguchi in Japan. Its simple tales of a man eating alone at various real-world restaurants is surprisingly appealing.

Kodoku no gurume (The Solitary Gourmet), illustrated by Taniguchi and written by Kusumi Masayuki, is the most popular work associated with Taniguchi in Japan. Its simple tales of a man eating alone at various real-world restaurants is surprisingly appealing.

Western Tokyo Dramas

Aruku hito (trans. The Walking Man) is another of Taniguchi’s 1990s works. A story told mainly by the pictures rather than the text, it has an atmosphere redolent of both bandes dessinées comics and the films of Ozu Yasujirō.

Aruku hito (trans. The Walking Man) is another of Taniguchi’s 1990s works. A story told mainly by the pictures rather than the text, it has an atmosphere redolent of both bandes dessinées comics and the films of Ozu Yasujirō.

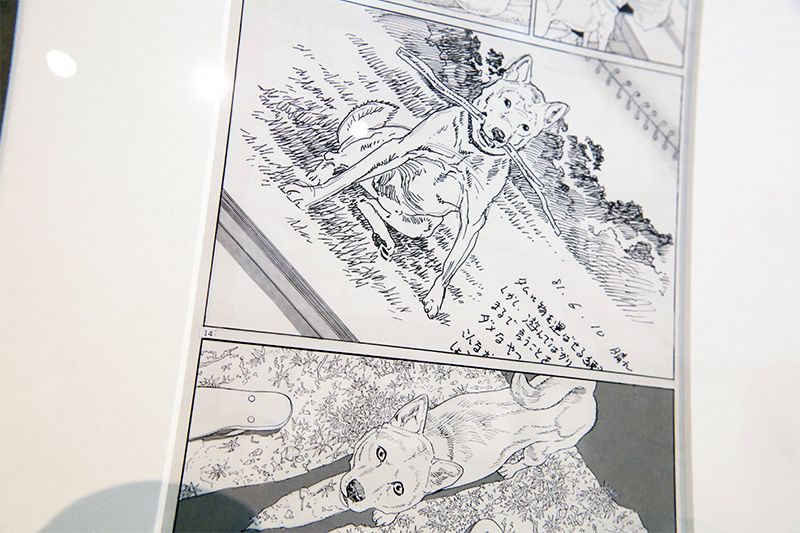

A kind of holy text for dog lovers, Inu o kau (Owning a Dog) warmly depicts the relationship between pet and owner.

A kind of holy text for dog lovers, Inu o kau (Owning a Dog) warmly depicts the relationship between pet and owner.

From the late 1990s to the 2000s, Taniguchi’s talent bore fruit in works like Ikaru (Icarus)—written by Mœbius—and A Distant Neighborhood. He won fans in France with his painstaking, detailed style in which he spent time to get each picture right rather than zipping on to the next panel.

The text for Kamigami no itadaki (trans. The Summit of the Gods) came from a recent hit mountaineering novel by Yumemakura Baku. Taniguchi adapted the large-scale work to the comic format. In the autobiographical Fuyu no dōbutsuen (trans. A Zoo in Winter), he traced his path from salaryman to mangaka.

The original picture for the cover of the mountaineering manga K.

The original picture for the cover of the mountaineering manga K.

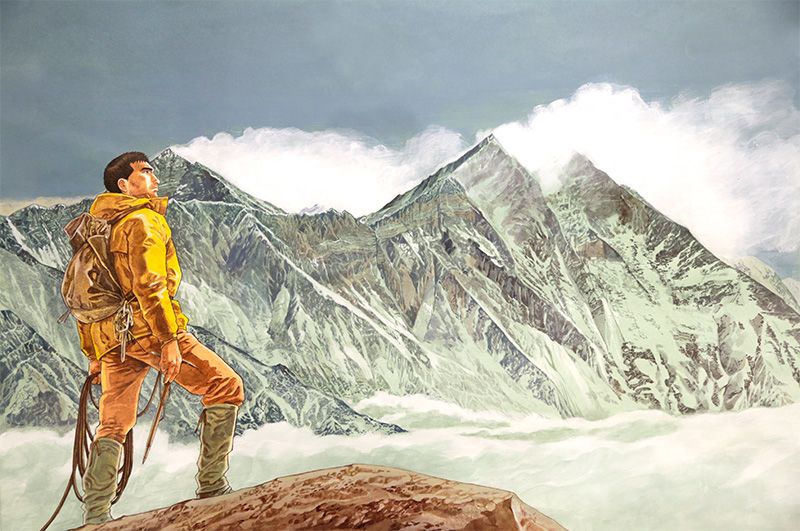

The original picture for the cover of Kamigami no itadaki (trans. The Summit of the Gods) has a power almost three-dimensional in nature.

The original picture for the cover of Kamigami no itadaki (trans. The Summit of the Gods) has a power almost three-dimensional in nature.

In his major works of the 2010s, Furari and Sennen no tsubasa, hyakunen no yume (trans. Guardians of the Louvre), he put an imaginative historical spin on the themes of The Walking Man in a fusion of Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées and Japanese manga styles. If only we could have seen more of this distinctive Taniguchi expression in further works.

Taniguchi was eager to adapt to manga Ryōken tantei (Hunting Dog Detective), a hard-boiled and heart-warming novel of man and dog written by Inami Itsura.

Taniguchi was eager to adapt to manga Ryōken tantei (Hunting Dog Detective), a hard-boiled and heart-warming novel of man and dog written by Inami Itsura.

The Tokyo exhibition displayed Taniguchi’s great ability and range. Yonezawa Shin’ya of the organizing Fondation Papier offered hints on how to enter the world of the mangaka.

“Taniguchi went to work in Kyoto after graduating from his Tottori high school, but left after six months and headed for Tokyo. He lived in the western suburbs of the capital for the rest of his life. Perhaps this is why you can sometimes see suburban Tokyo scenery in the background of his manga. You almost never see shitamachi low-town neighborhoods. While some of his works are set in his hometown, you could say his later output is drama that emerges from the scenery of west Tokyo. In this newly settled area, there are not the same strong ties to the neighborhood and land, so this is what gives his works their universal themes.”

(Originally published in Japanese on December 15, 2017. Reporting and text by Yoshimura Shin’ichi. Photographs by Nagasaka Yoshiki, courtesy of Fondation Papier. © Papier.)