Matsuri Days (1): A Guide to Asakusa and the Sanja Matsuri

Strolling Around Old Tokyo: Shops and Restaurants Where the Old Edo Spirit Lives On

Guideto Japan

Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

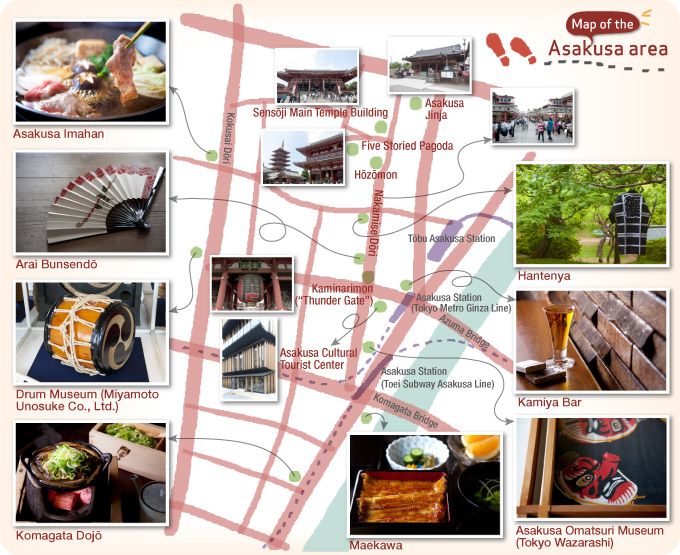

The Asakusa district of Tokyo is famous for preserving the spirit of the capital’s past. Visitors can still glimpse traces of the Edo period (1603–1868). The neighborhood revolves around Sensōji, a beloved Buddhist temple visited by millions of worshippers over the years. Thanks to this constant influx of people to Asakusa, restaurants and shops have long flourished in the area. Today, many of these establishments remain in business and carry on the old traditions.

(Clicking on one of the thumbnails below will take you to an article on that shop or restaurant)

(Originally written in Japanese by Motoyoshi Kyōko. Photographs by Katō Takemi and Kodera Kei.)

▼Click below for an interview with the rakugo storyteller Hayashiya Shōzō, who discusses some of the charms of the Asakusa area:

Komagata Dojō: A Traditional “Stamina Dish”

The dojō, or loach, is a freshwater fish often served at meals in the city of Edo (present-day Tokyo) during the Edo period (1603–1868). One such dish was dojō nabe, prepared by cooking several whole fish inside a pot with other ingredients, for a nutritious, energy-boosting meal.

One restaurant specializing in the dish is Komagata Dojō, established back in 1801. This Asakusa restaurant is located in the bustling area near Sensōji, and visitors to that famous temple often drop by for a meal. The delicious dojō nabe has made Komagata Dojō a neighborhood institution. The seventh-generation owner of the restaurant, Watanabe Takashi, explains more about this popular dish:

“Sake is poured over the fish while they are still alive. Once the alcohol takes effect, they are transferred to a sweet miso mixture and gently stewed. When it is done right, even the bones become soft. The recipe we use is largely unchanged from the Edo period. Many of our patrons have been eating here for years and we have a strong connection to the local area, which I think forms part of the appeal of our restaurant. Asakusa is a lively area of Tokyo but at night, it’s actually very quiet. Of course, that changes during the Sanja Matsuri, when Asakusa is lively from morning until late at night.”

The stamina-packed dish dojō nabe from the Edo period perfectly suits Asakusa, with its rich traditions and overflowing energy.

Tatami room on the ground floor

Tatami room on the ground floor

A photo of the restaurant in 1907

A photo of the restaurant in 1907

The dish “dojō nabe” (¥1,750) comes with a generous portion of spring onions. It is said that a shallow pan was used so the dish could be heated up and served as quickly as possible to the busy residents of Edo.

The dish “dojō nabe” (¥1,750) comes with a generous portion of spring onions. It is said that a shallow pan was used so the dish could be heated up and served as quickly as possible to the busy residents of Edo.

Watanabe Takashi, the seventh-generation owner of Komagata Dojō, calls “dojō nabe” the “fast food of the Edo period,” and says that “many local peddlers visited the restaurant early in the morning to spend their earnings on a hot meal.”

Watanabe Takashi, the seventh-generation owner of Komagata Dojō, calls “dojō nabe” the “fast food of the Edo period,” and says that “many local peddlers visited the restaurant early in the morning to spend their earnings on a hot meal.”

The “dojō” loach fish are cultivated in quiet subterranean waters of Ōita Prefecture, then delivered to the restaurant alive to ensure freshness for customers.

The “dojō” loach fish are cultivated in quiet subterranean waters of Ōita Prefecture, then delivered to the restaurant alive to ensure freshness for customers.

Komagata Dojō

Komagata Dojō

Address: 1-7-12 Komagata, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-3842-4001

Hours: 11:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. (every day of the year)

Reservations possible for four persons or more

English menu available

Average prices: ¥3,000 for lunch, ¥5,000 for dinner

http://www.dozeu.com/

Maekawa: Serving Traditional Eel Dishes for 200 Years

Maekawa is an Asakusa restaurant specializing in eel, established at the start of 19th century. As its sixth-generation owner, Ōhashi Hajime, explains, the restaurant can trace its origins back to a meager stall located on the banks of the Sumida River that sold eel and sake to the locals:

“Back then, many customers would come to the area by boat. Eating eel and sipping a cup of sake while gazing out on the river was a popular pastime, especially when the cherry blossoms were in bloom. The place was also said to be a popular rendezvous for lovers.”

These days it is common to cook eel quite lightly before serving, but that only started in the middle of the Edo period. Compared to western Japan, the eel in the area around Edo had a thicker skin. This made it necessary to gently steam the eel first, and then coat it with sauce and grill over charcoal. That is the cooking style used at Maekawa to prepare eel. The key to the taste is the sauce, which has been passed down and enhanced over the generations.

“I think the charm of Asakusa is how its culture and scenery combine the old with the new,” Ōhashi notes. “Just across the Sumida River, for instance, we now have a spectacular view of the ultra-modern tower, Tokyo Skytree, which opened in June 2012,”

Ōhashi Hajime, the sixth-generation owner of Maekawa, with Tokyo Skytree in the background.

Ōhashi Hajime, the sixth-generation owner of Maekawa, with Tokyo Skytree in the background.

The eel dish “unajū” at Maekawa (from ¥4,095). It takes 30 minutes for the eel to arrive because it is steamed after each individual order is placed. The appetizer “kimoyaki” (¥1,260), which goes great with beer, can fill the gap while you’re waiting.

The eel dish “unajū” at Maekawa (from ¥4,095). It takes 30 minutes for the eel to arrive because it is steamed after each individual order is placed. The appetizer “kimoyaki” (¥1,260), which goes great with beer, can fill the gap while you’re waiting.

Sauce is poured over the eel three times during the roasting process.

Sauce is poured over the eel three times during the roasting process.

The sauce’s recipe has been honed to perfection over the generations.

The sauce’s recipe has been honed to perfection over the generations.

Maekawa

Maekawa

Address: 2-1-29 Komagata, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-3841-6314

Hours: 11:30 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. (every day of the year)

Reservations possible.

English menu available.

Average prices: ¥5,000; set courses from ¥9,450

http://www.unagi-maekawa.com/

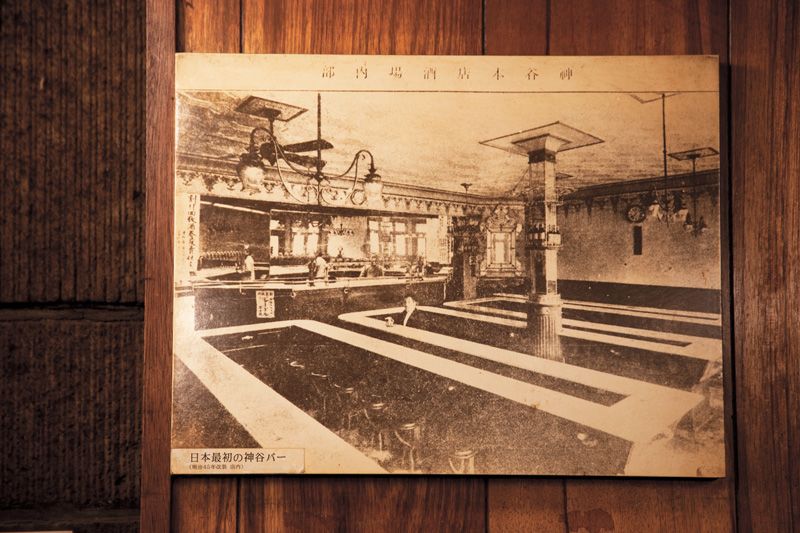

Kamiya Bar: The Famous Cocktail at the First Bar in Japan

Kamiya Bar was established in 1880 as Japan’s first bar. Today it remains a popular watering hole in the old shitamachi area of Tokyo, famous for its original Denki Bran cocktail created soon after the bar opened. “Denki” is the Japanese word for electricity, which was still a rare thing when the bar was established. Electrical goods and products that came from abroad and looked very new often had names with the denki- prefix. “Bran” is short for the cocktail’s main alcoholic ingredient, brandy. Other ingredients are gin, wine, Curaçao, and herbs, resulting in a slightly sweet flavor. There is also a similar cocktail, called Denki Bran Old, with an alcohol content somewhere between 30% and 40%.

“The originally conceived recipe for Denki Bran is still a trade secret to this day. People say that the flavor brings back feelings of nostalgia, even if they drink it for the first time,” says the fifth owner, Kamiya Naoya.

Some snacks often served with a Denki Bran are pieces of stewed beef, or fried pork and onion on skewers. Many people like to wash it all down with a draft beer too. Along with its famous cocktail, Kamiya Bar has a low-key, unpretentious atmosphere that sets it apart from other drinking establishments. Go for a visit to experience what Asakusa felt like back in the old days.

Over 150 seats available in the bar

Over 150 seats available in the bar

The famous amber colored cocktail, Denki Bran (¥260); you can also try a Denki Bran Old (¥360).

The famous amber colored cocktail, Denki Bran (¥260); you can also try a Denki Bran Old (¥360).

In the Meiji era, customers sat at long counters to drink.

In the Meiji era, customers sat at long counters to drink.

Kamiya Bar

Kamiya Bar

Address: 1-1-1 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-3841-5400

Hours: 11:30 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. (closed Tuesdays)

Reservations possible (up to eight people; weekdays only)

English menu available.

Average meal price: ¥2,000

http://www.kamiya-bar.com/

Asakusa Imahan: Sukiyaki Made with Japan’s Finest Beef

Asakusa Imahan is famous for its sukiyaki, or thinly sliced beef cooked in a pot. When the restaurant opened, back in 1895, it was still unusual in Japan to eat beef. Since sukiyaki was such a rare treat at the time, the restaurant’s popularity grew quickly.

Over its 100-plus years in business, the restaurant has continued to insist on using the finest ingredients, starting with the wagyū beef. Asakusa Imahan only uses the beef of “Japanese Black” cows from Kobe, carefully selecting each shipment.

Sukiyaki involves slowly simmering the beef inside a pot filled with bubbling soup. The beef is served raw at the table, and then freshly cooked in the broth with vegetables and other ingredients. As soon as the beef and vegetables are cooked through, customers can serve themselves with their chopsticks.

The pots used to cook sukiyaki at Asakusa Imahan are made by craftsmen in a style called nanbu tekki, a traditional kind of ironware from Iwate prefecture. As the beef begins to cook in the broth, a wonderful aroma fills the room. A waitress can prepare the sukiyaki for you, judging the perfect amount of time to cook the beef. The fifth-generation owner of the restaurant, Takaoka Shūichi, tells us more:

“I think Asakusa is the area of Tokyo where you can most feel the spirit of the Edo period. You really get a sense of the strong influence the Sensōji temple has had on Asakusa over the years.”

Consider visiting Asakusa Imahan for unique gastronomic experiences, set in a bustling, tradition-rich neighborhood of Tokyo.

The fifth-generation owner of the restaurant, Takaoka Shūichi, says his grandfather came up with the idea for the beef “tsukudani” sold as a take-away gift at the restaurant.

The fifth-generation owner of the restaurant, Takaoka Shūichi, says his grandfather came up with the idea for the beef “tsukudani” sold as a take-away gift at the restaurant.

“Gokujō shimofuri sukiyaki gozen” served for two (¥10,500 per person), which literally means “a feast of the finest marbled beef sukiyaki.”

“Gokujō shimofuri sukiyaki gozen” served for two (¥10,500 per person), which literally means “a feast of the finest marbled beef sukiyaki.”

1. Pour a small amount of “warishita” (a mixture of soy sauce, “mirin,” and sugar) into the heated “nanbu tekki” iron pot (enough to cover half of the pan’s surface). 2. Before the “warishita” boils, gently beat an egg with chopsticks, being careful to avoid forming bubbles. 3. Place two slices of beef on areas of the pot not covered by the “warishita”; once the beef is slightly cooked stir the “warishita” around the pan to mix it with the meat. 4. Once the flavor and juices from the meat have dissolved into the “warishita,” add vegetables and tōfu to the mix.

1. Pour a small amount of “warishita” (a mixture of soy sauce, “mirin,” and sugar) into the heated “nanbu tekki” iron pot (enough to cover half of the pan’s surface). 2. Before the “warishita” boils, gently beat an egg with chopsticks, being careful to avoid forming bubbles. 3. Place two slices of beef on areas of the pot not covered by the “warishita”; once the beef is slightly cooked stir the “warishita” around the pan to mix it with the meat. 4. Once the flavor and juices from the meat have dissolved into the “warishita,” add vegetables and tōfu to the mix.

More beef can be added as the mixture simmers in the pot, but it should not be overcooked, with a small amount of pink remaining.

More beef can be added as the mixture simmers in the pot, but it should not be overcooked, with a small amount of pink remaining.

The waitress makes sure that each piece of beef is cooked to perfection.

The waitress makes sure that each piece of beef is cooked to perfection.

Asakusa Imahan

Asakusa Imahan

Address: 3-1-12 Nishiasakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-3841-1114

Hours: 11:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. (every day of the year)

Reservations available.

English menu available.

Average prices: ¥3,000–4,000 for lunch, ¥10,000 for dinner

http://www.asakusaimahan.co.jp/english/index.html

Arai Bunsendō: Exquisite Hand-Held Fans

Hand-held fans have—in addition to their ordinary uses—long been an accessory used in the traditional Japanese arts. They are indispensable for performers in the arts of kabuki, traditional dance, and rakugo (comic storytelling).

The designs of Edo-period fans were superb, often using bold themes and incorporating large white spaces. One design of the period, for example, features only the head and the tail of a dragon, painted on the edges of the fan. This approach of hiding the body creates the impression that the dragon is enormous.

Arai Bunsendō is a shop that has been selling hand-held fans for over 120 years, with a clientele that includes kabuki performers, dancers, and rakugo storytellers. Its fourth-generation owner, Arai Osamu, designs and creates the fans by hand. “It’s crucial to create a design that is sharp and appealing,” he emphasizes.

Fans displaying a kabuki motif are particularly popular among the shop’s customers, some of whom ask for a design that corresponds to the content of a play that they are going to see.

Arai Bunsendō has built up its popularity over the years by providing beautiful hand-held fans that are as sophisticated as the culture of Asakusa.

The “shibusen” style fan, whose color results from repeatedly dying using persimmon juice. Samurai once used this type of fan. The small fan (for women) is priced at ¥3,040, and the larger version (for men) is ¥3,460.

The “shibusen” style fan, whose color results from repeatedly dying using persimmon juice. Samurai once used this type of fan. The small fan (for women) is priced at ¥3,040, and the larger version (for men) is ¥3,460.

“Mochisen” fans with a kabuki theme.

“Mochisen” fans with a kabuki theme.

Two fans featuring original designs (¥550 each).

Two fans featuring original designs (¥550 each).

The fourth-generation owner of Arai Bunsendō, Arai Osamu, who is dedicated to creating unique fan designs.

The fourth-generation owner of Arai Bunsendō, Arai Osamu, who is dedicated to creating unique fan designs.

The spine of the fan is fixed at the bottom.

The spine of the fan is fixed at the bottom.

Arai Bunsendō

Arai Bunsendō

Address: 1-20-2 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-3841-0088

Hours: 10:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. (closed the Monday after the 20th of every month)

No minimum quantity for custom-made fan orders

No English explanatory materials

Prices: “mochisen” fans from ¥1,100; handcrafted fans from ¥8,200 for women’s versions and ¥8,900 for men’s versions

Tokyo Wazarashi: Edo-Period Fashions Live On

Tokyo Wazarashi was originally established in 1889 as a factory for dying cotton materials white. Its fourth-generation owner, Takizawa Ichirō, explains more about the manufacturing process:

“After bleaching the cotton materials, you can add vivid colors and patterns to create yukata [casual summer kimonos worn by men and women] and tenugui [decorative hand towels]. Looking at how well the materials are dyed white reveals the skill level of the craftsman.”

In the 1960s, Tokyo Wazarashi had a large workforce and supplied a third of all the white cloth used in Japan for making yukata. Demand for yukata fell in subsequent years, however, along with a general decline in the popularity of traditional Japanese clothing.

In contrast, tenugui towels have become more and more popular over the years. Among their other uses, the long, rectangular towels can be folded and wrapped round the head like a bandana—a style that dates back to the Edo period. Tokyo Wazarashi makes tenugui to order, and these customized items account for 90% of all towels sold at the shop.

Tokyo Wazarashi has also opened the Asakusa Omatsuri Museum to showcase the iconic matsuri (festivals) in Asakusa, particularly Sanja Matsuri, which is in a class of its own—as Takizawa explains: “We decided to start up the museum as a way of capturing the spirit of Asakusa, which is overflowing with energy, and the sense of solidarity between its residents.” In addition to explaining the culture surrounding Asakusa festivals, the museum displays examples of the kinds of garments worn during these events.

Handmade paper stencils used for dying.

Handmade paper stencils used for dying.

A “tenugui” that has been dyed using the stencils.

A “tenugui” that has been dyed using the stencils.

The fourth-generation owner of Tokyo Wazarashi, Takizawa Ichirō.

The fourth-generation owner of Tokyo Wazarashi, Takizawa Ichirō.

Some hand-dyed “tenugui” that are priced between ¥800 and ¥1,000. Order-made versions cost ¥30,000 for a batch of 100, or ¥50,000 if the order requires dying by hand.

Some hand-dyed “tenugui” that are priced between ¥800 and ¥1,000. Order-made versions cost ¥30,000 for a batch of 100, or ¥50,000 if the order requires dying by hand.

Tokyo Wazarashi

Address: 4-14-9 Tateishi, Katsushika-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-3693-3334

http://www.tenugui.co.jp/

Hantenya: Festive Clothing and Goods

Typical Asakusa residents often have clothing and items specially made for festive occasions. One traditional item of clothing often seen at festivals is the hanten—a short jacket worn by both men and women. One shop specializing in hanten and other festival-related items is Hantenya. The owner and founder, Kojima Akihiro, grew up in a draper’s shop that had operated for over 100 years in Asakusa. He decided to open up his own shop sell clothing and goods for festivals to his friends.

“Festivals make Asakusa what it is,” Kojima says. “The friendships I have made with people in the area have been the result of strong bonds created during the local festivals, especially the Sanja Matsuri. Starting this business was a way for me to support and promote these events.”

Many of the clothing items sold at Kojima’s shop are originals, carefully created by hand and dyed individually. Underneath the hanten, many people wear shirts that have images of koi carp. Hantenya sells over 100 different kinds of these shirts. The shop aims to appeal to the clientele of “old Tokyo” and also produce small lots of originally designed items that stand apart from the usual, factory-produced products found elsewhere.

The owner of Hantenya, Kojima Akihiro

The owner of Hantenya, Kojima Akihiro

”Koi” carp shirts, priced at around ¥3,980 (hand-dyed shirts from ¥4,900).

”Koi” carp shirts, priced at around ¥3,980 (hand-dyed shirts from ¥4,900).

A winter “hanten” of the sort often worn by common people in the Edo period. The regular type costs ¥2,500 (hand-dyed versions in a plain and a patterned style are priced, respectively, from ¥20,000 and from ¥28,000).

A winter “hanten” of the sort often worn by common people in the Edo period. The regular type costs ¥2,500 (hand-dyed versions in a plain and a patterned style are priced, respectively, from ¥20,000 and from ¥28,000).

Hantenya

Hantenya

Address: 1-37-11 Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

Tel: 03-5827-0852

Hours: 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. (closed Wednesdays)

No explanatory materials in English.

http://www.hantenya.com/

Drum Museum : See Percussion Instruments from Around the World

Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd., founded in 1861, is well known for having built the replacement mikoshi now used in the Sanja Matsuri. Originally, the company produced equipment and other items used in festivals, such as taiko drums. These drums were an important part of the lives of common people during the Edo period (1603–1868). Towns around castles had shops that sold taiko, and the drums were used to broadcast the time of day to town residents.

Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd., founded in 1861, is well known for having built the replacement mikoshi now used in the Sanja Matsuri. Originally, the company produced equipment and other items used in festivals, such as taiko drums. These drums were an important part of the lives of common people during the Edo period (1603–1868). Towns around castles had shops that sold taiko, and the drums were used to broadcast the time of day to town residents.

To this day, the company still makes taiko used in Buddhist and Shinto ceremonies and traditions, as well as many taiko used for traditional performing arts, such as kabuki, nō, and gagaku (classical music from the imperial court). Musicians have long praised the high quality of Miyamoto Unosuke drums.

India has over 250 different kinds of percussion instruments.

India has over 250 different kinds of percussion instruments.

Based on this heritage, the company in 1988 founded the Drum Museum (Taiko Kan), which features not only Japanese drums (taiko), but also drums and percussion equipment from all over the world. The museum’s collection includes over 900, of which 200 are typically displayed at any given time. Visitors are able to touch and use many of the drums on display.

The percussion instruments in the museum are from a diverse range of regions, and come in all shapes and sizes. Some drums are struck with the hands, some are played with sticks, while others produce a sound by rubbing two parts of the instrument together.

“India has an abundant variety of types of percussion instrument—over 250 of them,” notes the museum’s curator, Arikawa Junko. “Many have been passed down from generation to generation for over 2,000 years. When you look closely at the instruments from various regions of the world, you can see some fundamental shapes and configurations in common despite how geographically remote they are from each other.” Arikawa says she is keen for visitors to experience the unpredictability and fascination of drums.

A “garamut” from Papua New Guinea, used as a tool for communication; by striking the drum in a particular way, different meanings can be conveyed.

A “garamut” from Papua New Guinea, used as a tool for communication; by striking the drum in a particular way, different meanings can be conveyed.

A “kaze-no-oto” from Japan. If you rotate the lever in front clockwise, the instrument produces the sound of the wind. Simulating the sounds of nature is a common characteristic of instruments from Japan.

A “kaze-no-oto” from Japan. If you rotate the lever in front clockwise, the instrument produces the sound of the wind. Simulating the sounds of nature is a common characteristic of instruments from Japan.

A “balafon” from Africa, which sounds much like a xylophone. Underneath the wooden keys are resonators made from the calabash fruit.

A “balafon” from Africa, which sounds much like a xylophone. Underneath the wooden keys are resonators made from the calabash fruit.

A “cuíca” from Brazil. A sound is produced by rubbing a wet cloth across the surface on the rear of the instrument.

A “cuíca” from Brazil. A sound is produced by rubbing a wet cloth across the surface on the rear of the instrument.

To hear what these instruments sound like, play the video below.

A “nagadō daiko” from Japan. Depending on whether the drum is for ceremonial purposes or for musical performances, the leather part is affixed differently. In the version used for musical performances (pictured above), the leather is rebound when it gets loose, so there is a spare amount behind the bindings used to pull the leather back and increase the tension. The leather on the version used for religious ceremonies (pictured below) is never rebound and the appearance is more important. Therefore, the leather is cleanly cut off behind the bindings, with no amount to spare.

A “nagadō daiko” from Japan. Depending on whether the drum is for ceremonial purposes or for musical performances, the leather part is affixed differently. In the version used for musical performances (pictured above), the leather is rebound when it gets loose, so there is a spare amount behind the bindings used to pull the leather back and increase the tension. The leather on the version used for religious ceremonies (pictured below) is never rebound and the appearance is more important. Therefore, the leather is cleanly cut off behind the bindings, with no amount to spare.

The ground floor of the Nishi Asakusa Store, which sells lots of festival-related goods.

The ground floor of the Nishi Asakusa Store, which sells lots of festival-related goods.

A genuine leather strap to attach to your cell phone, keys, or bag; the one in front is the “nagadō daiko” and costs ¥1,785 and the strap behind it costs ¥1,260.

A genuine leather strap to attach to your cell phone, keys, or bag; the one in front is the “nagadō daiko” and costs ¥1,785 and the strap behind it costs ¥1,260.

“Shishimai” (Lion Dance), a type of “satokagura” (Shinto based ritual). Pictured on the right is the male creature “Uzu,” and on the left the female “Gonkurō”; in the foreground are some bean bags for juggling (¥630).

“Shishimai” (Lion Dance), a type of “satokagura” (Shinto based ritual). Pictured on the right is the male creature “Uzu,” and on the left the female “Gonkurō”; in the foreground are some bean bags for juggling (¥630).

Drum Museum

Drum Museum

Address: Miyamoto Unosuke Co. Ltd, Nishi Asakusa Store Building 4F, 2-1-1 Nishi-Asakusa, Taitō-ku, Tokyo

Tel: +81 3-3842-5622

Hours: 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.; closed Mondays (except national holidays) and Tuesdays

Some English explanatory materials available.

http://www.miyamoto-unosuke.co.jp/english/taiko.html

Edo Asakusa Matsuri Sensoji Nakamise rakugo Komagata Dojo Maekawa unagi Imahan restaurants sukiyaki tenugui hanten Kamiya Bar Tokyo Wazarashi fan Arai Bunsendo