“Cool Traditions” Stay in Tune with Modern Life

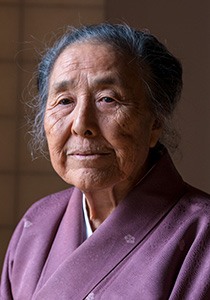

Spreading the Spirit of Tea in Europe: Nojiri Michiko

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Urasenke organization today operates 111 locations in 37 countries around the world. When Nojiri Michiko (also known by her tea name, Sōmei) made her way over to Rome 55 years ago, however, Europeans were almost completely unfamiliar with the art of tea. Meanwhile, in the United States, Okakura Kakuzō’s The Book of Tea, written in English, had been out for over a half century, and the then Urasenke head, Sen Sōshitsu XV (presently known as Sen Genshitsu), had already begun work on creating Urasenke’s first place of practice in Hawaii. Sōshitsu harbored doubts about whether the tea ceremony could ever catch on in European countries due to their longstanding cultures and traditions. But when Nojiri’s tea instructor told him that she was about to embark for Rome to study art on a scholarship, he decided to put the young woman in charge of investigating the European market for the Japanese way of tea, sending her off with a woven rush mat the size of four and a half tatami mats and a set of implements for the practice.

A lengthy sea voyage finally brought Nojiri to Rome, where the first thing she bought herself was a used car at a remarkably low price. She loaded her car, packed her tatami mats on the roof and her tea implements in the passenger’s seat, and began travelling around Europe to give tea demonstrations.

“D. T. Suzuki’s essays on Zen Buddhism were spreading around Europe at the time, so I felt that the groundwork had already been laid for us, that people would be able to understand the art of tea for the kind of spiritual culture that it is.”

Nojiri in the tea room of the Urasenke Rome branch, sitting next to her own collection of hina dolls, in March 2018.

Nojiri in the tea room of the Urasenke Rome branch, sitting next to her own collection of hina dolls, in March 2018.

The Birth of Centro Urasenke

In 1969, Nojiri was tasked by Sen Sōshitsu XV with opening an Urasenke branch in Rome. Having found a stately building in the quiet Prati district of the city, Nojiri was told by the building owner that she was free to renovate the apartment. She converted a dining room into a tea room, taking out the partitions of two other rooms and a hallway to create a wide-open space where she could hold chanoyu tea gatherings. This was the Centro Urasenke.

The entrance to the Urasenke Rome branch. The thoroughly Western-style door opens onto a Japanese tea space whose architectural design Nojiri supervised.

The entrance to the Urasenke Rome branch. The thoroughly Western-style door opens onto a Japanese tea space whose architectural design Nojiri supervised.

A hengaku, a placard with a motto inscribed by Sen Sōshitsu XV, sits above the entrance to the tea room, declaring it to be the 好日軒 (roughly translating to “the home of pleasant days”).

A hengaku, a placard with a motto inscribed by Sen Sōshitsu XV, sits above the entrance to the tea room, declaring it to be the 好日軒 (roughly translating to “the home of pleasant days”).

Teaching Tea from a Different Angle

Nojiri took unique steps to allure prospective students. She cultivated relationships with musicians, painters, sculptors, poets, and other artists, working all the while to spread knowledge of the art of tea throughout their ranks. “Even before the tea room was completed, I would invite them each month to the Japanese cultural center in Rome, where I would hold tea demonstrations. I gave detailed lectures on the spirit of tea and on the gardens, rooms, and implements associated with the practice, so that once the tea room was ready, they would come calling and invite their friends along as well.”

Nojiri also worked at forming a connection to the Vatican and was very active in building a close relationship with priests. Fortunately, in 1965, as a result of the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church announced it would undertake revised ecumenical efforts towards other religions, sects, and philosophies. Even if there had been priests up to that point who had even a slight interest in Zen Buddhism, the simple act of visiting a Zen temple, much less conversing with a Zen priest, was prohibited under Catholic law. Following Vatican II, though, priests started to come to Nojiri to learn about tea and zazen practice.

“Perhaps what resonated with the priests was how the spirit of tea goes beyond religion to manifest itself in everyday actions; that through the practice of tea, the practitioner is able to shed the self. This is something that tea and religion both share. I believe that it is easy for priests to communicate through the language of tea as they are engaging in the same sort of ritualistic behavior, through prescribed actions and formalities, whenever they hold mass.”

Nojiri maintains her relationship with the Vatican to this day. In May 2017, in celebration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of establishing diplomatic relations between Japan and the papacy, she held a tea gathering at the residence of the Japanese Ambassador to the Vatican.

Nojiri’s Italian Pupil

One person who has had a profound impact on how Nojiri has taken to introducing the Japanese way of tea to Europe is her right-hand woman, an Italian by the name of Emma Di Valerio. Di Valerio, formerly a Latin teacher, was introduced to Nojiri at an acquaintance’s house in May 1963. The two hit it off, both sharing a passion for mountain climbing, and Di Valerio, who already had an interest in Japanese culture and had been studying the language and Nihonga painting, said that she had been eagerly waiting for the Urasenke branch in Rome to open, even practicing tea in anticipation of its arrival. The two started working together to translate literature related to the art of tea into Italian. Their first projects included Lu Yu’s The Classic of Tea, Sen no Rikyū’s One Hundred Poems, and Southern Record, a text presenting secret teachings of Rikyū; Nojiri would translate and Di Valerio would edit her Italian versions.

Di Valario explained to Nojiri, who was still in the process of determining how she would establish the guiding principles for teaching tea in Europe, that Europeans had a greater interest in the philosophical basis rather than the formalities of the practice, and that she wanted to get to the heart of what chanoyu represented. Otherwise, Europeans were more likely to simply want to enjoy a cup of tea in a more relaxed manner.

Nojiri Sōmei at right with her first pupil, Emma Di Valerio Sōsei. After Nojiri retired as the director of the Rome branch last year due to advanced age, Di Valerio became one of the members who took over for her.

Nojiri Sōmei at right with her first pupil, Emma Di Valerio Sōsei. After Nojiri retired as the director of the Rome branch last year due to advanced age, Di Valerio became one of the members who took over for her.

Di Valerio placing charcoal in the hearth to boil water. Nojiri traveled three hours each way to the outskirts of Florence to bring back a year’s worth of charcoal for the school in a station wagon.

Di Valerio placing charcoal in the hearth to boil water. Nojiri traveled three hours each way to the outskirts of Florence to bring back a year’s worth of charcoal for the school in a station wagon.

“Here in Rome, we have no proper tea rooms. All I have with me are my implements and things to practice with, so the only thing I would be able to teach my students would be ‘the soul of tea.’ It was Emma who made me aware of that fact. When Japanese people take up tea, they tend to focus their attention on learning the proper etiquette and manners of performing it. However, what Europeans are looking for when they start to learn it is the deep connections chanoyu can bring about between people; the calm; the tranquility of the practice. I believe that by studying tea, the learner gains these things and is able to apply them to different aspects of their everyday lives, which is precisely what has made it so appealing to people over here.”

In 1974, the fifteenth head of the Raku family of tea-bowl makers, Raku Kichizaemon, went to Rome to study. There he learned the basics of tea from Di Valeri, and travelled with Nojiri to tea demonstrations and to academic seminars on psychology and other conventions on Eastern and Western culture in West Germany. Raku had until then been skeptical of Japanese traditions, but said that it was Nojiri who opened his eyes to the world of tea.

Focusing on Breathing and Posture

When it comes to teaching beginners, the first thing Nojiri teaches is not etiquette or procedure, but rather correct breathing and posture. “I have them stand with their feet slightly separated, tighten their abdominal muscles, and check whether they are breathing properly. I then have them make a large circle with their arms, as if they were giving a bear hug. They practice this for several months until they are aware of their ‘energy center’ located just below their navel.” For non-Japanese, who are not used to sitting on their knees in the seiza position on the floor, by doing this they can learn the proper posture to take while sitting and will maintain that posture even when relaxed.

“The foundation of the way of tea is heart-to-heart exchanges between host and guest, meaning that calming one’s soul, relieving all tension, and moving fluidly are absolutely imperative. To make sure your posture, breathing, and actions are all in line is a difficult thing to do. If you become preoccupied with your movement, your breathing becomes unsteady. Being able to remain calm and adapt to the situation is the goal of practicing tea, while the soul of tea is in being able to construct an atmosphere of calm regardless of the situation.”

Putting the Mind in Order

A pupil of Nojiri’s, Andrea Falla Sōan, practices making formal koicha thick tea.

A pupil of Nojiri’s, Andrea Falla Sōan, practices making formal koicha thick tea.

On the day we went to shoot photos, a bank employee by the name of Andrea Falla, who has received the tea name Sōan, came for practice. He is just one of the people upon whom Nojiri’s instruction had left a deep impact. “In all the hustle and bustle of our everyday lives, we tend to lose sight of ourselves. But by practicing tea in peace and calm, we are able to retrieve who we are. I regain tranquility in my life when I practice tea, and I endeavor to retain that state of mind even after I’ve left the tea room.”

Nojiri states: “If I were to simply teach my European pupils the etiquette and procedure of tea, then it wouldn’t ever amount to anything more than just an interest in exoticism. If they view it as such then they won’t continue the long process of learning the art form. When I teach my pupils, whether they’re from Italy, Belgium, Spain, Switzerland, Austria, Germany or Romania, to approach diaphragmatic breathing and zazen as a means to put their mind in order—or when I see them learning tea as a means to understand the emotional connection between host and guest—it brings me great joy.”

After a lifetime of reflecting on what lies at the heart of tea that makes it uniquely Japanese and about what can be universally conveyed through tea, Nojiri opines that “It’s about always being calm and always having an open mind.”

Conveying the spirit of Japan’s way of tea in Europe, a place where so many different traditions, religions, and ways of thought come together, must have held a number of unfathomable difficulties. Still, Nojiri endeavored herself to learn the history, customs, cultures, not to mention several foreign languages, and despite having a number of pupils under her wing, still finds those who wish to learn tea from her even to this day.

On the day of our interview, Nojiri even went out for a two-hour ride on her horse. The next day she set off for a trip to Ireland, where she would visit a tea practice session at the behest of the first two German pupils she ever took on, the Bastians. The German couple moved to the Irish countryside and added a tea room onto their home. There they continue to practice tea along with their fellow students, showing how the spirit Nojiri has spread throughout Europe continues to flourish all over the region to this day.

Nojiri and one of her German pupils, Winfried Bastian, enjoying a ride nearby his home in Ireland. At right, the group during practice in the tea room that, except for tatami mats, the Bastians built themselves. (© Nojiri Michiko)

Nojiri and one of her German pupils, Winfried Bastian, enjoying a ride nearby his home in Ireland. At right, the group during practice in the tea room that, except for tatami mats, the Bastians built themselves. (© Nojiri Michiko)