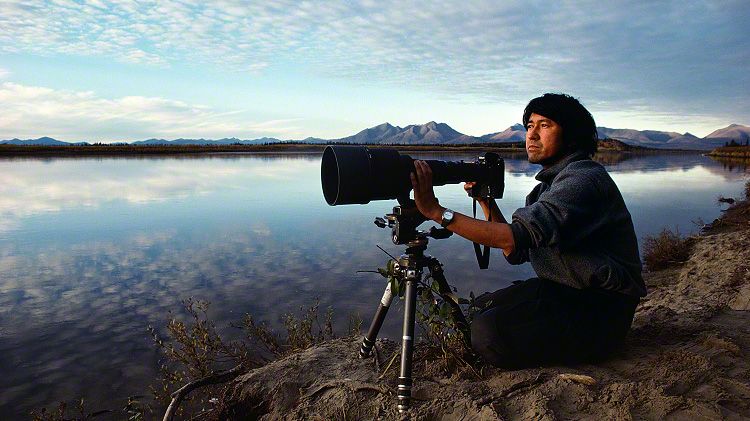

Visions of Alaska: Remembering Japanese Photographer Hoshino Michio

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

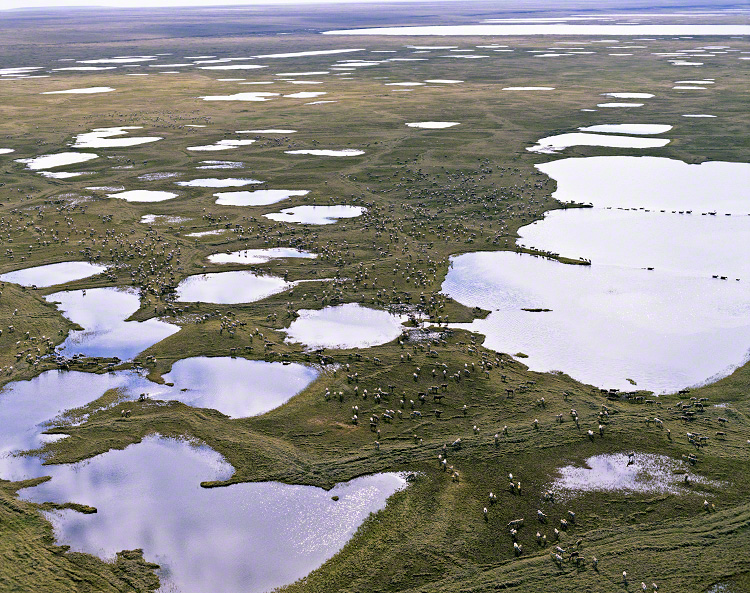

The award-winning photographer Hoshino Michio (1952–96) had an innate talent for capturing intimate moments from the wilds of Alaska. His photos are slivers of time that show his subjects, sometimes no more than tiny figures in the foreground, set amid vast expanses of forest, sea, mountain, tundra, or ice. Through Hoshino’s lens viewers are present for such timeless Arctic scenes as polar bears sauntering side by side through an expansive, frozen environment, a herd of caribou fording a mirror-smooth river, and the Aurora Borealis dancing across the rolling, snow-covered landscape.

A mother polar bear and her cubs in a world of snow.

Hoshino was also a talented writer who eloquently conveyed the human face of Alaska in his thoughtful essays. He traversed the Alaskan landscape for nearly two decades, telling the stories of the land and its inhabitants, until his journey was tragically cut short by a bear attack in a wildlife reserve in Kamchatka, Russia, on August 8, 1996. But even now, 20 years since his death, his works retain their capacity to enchant and inspire with candid depictions of life and nature in the north.

A herd of caribou migrates across the Arctic tundra.

Arctic Dreams

Hoshino was born in 1952 in Ichikawa, Chiba Prefecture. As a boy he developed a strong love of reading, a trait he kept his entire life. He enjoyed a broad range of books, including the works of early-twentieth-century wildlife artist Ernest Thompson Seton (1860–1946). As he matured he developed an interest in nature and took to hiking and exploring the wilds of Japan. Motivated by the desire to experience a different world, at age 16 he traveled solo around North America, where he visited cities like Los Angeles and New York along with such natural wonders as the Grand Canyon.

In university Hoshino developed a strong interest in Alaska and began collecting bits and pieces of information about the state. He had long been a regular in the used-book stores of Tokyo’s Kanda district, and it was here that he found a grainy photo of Shishmaref, a rugged Eskimo village on the blustery Bering Sea coast that was to become the starting point of his Alaskan journey. The photograph, printed in a National Geographic pictorial book, awakened in Hoshino a keen longing to experience life in the tiny, snow- and sea-swept settlement. In Arasuka hikari to kaze (Alaska, Her Lights and Winds) he writes: “I wondered why people had to live in such a bleak environment. What did they eat? How did they live? I desperately wanted to experience these things firsthand and felt that among these people I would discover something that would dramatically change how I understood the world.”

An Eskimo hunting party chases whales on the Arctic Ocean.

Hoshino innocently penned a letter, addressing it simply: Mayor, Shishmaref, Alaska. To his surprise, half a year later a response arrived, and in the summer of 1973 he spent three months as part of the small community. Staying with a local family, he embraced every aspect of native life, letting the sights, sounds, and smells of the village wash over him.

A humpback whale breaches.

Hoshino returned to the state in 1978 to study wildlife biology at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Back in Japan he had studied photography as an assistant to the veteran photographer Tanaka Kōjō, and he put his skills to work almost immediately upon touching down. Over the following 18 years he traveled repeatedly to every corner of the state, often taking only a few days to recoup, share stories with friends, and prepare his gear before dashing off for another extended wilderness stay. He was blessed with boundless patience and respect for the capriciousness and power of nature, enabling him to endure the most extreme elements, often for weeks on end, while waiting for his subjects to appear. He existed in the moment, cherishing the ancient ebb and flow of the Alaskan seasons.

In his essay “Kitaguni no aki” (Autumn in the North), published in the collection Tabi o suru ki (The Traveling Tree), Hoshino says: “We can clearly sense the eternal flow of time in the progress of the seasons. They are such graceful arrangements of nature. They arrive once a year and are gone before we realize, leaving us to wonder about the number of times we will have to enjoy their beauty. There may be no better way to understand the transience of life than by counting each passing season.”

Polar bears resting on the ice.

Behind the Camera

Hoshino enjoyed a level of success few photographers achieve. His works were widely published and featured in exhibits in his own Japan and around the world. He also won photography accolades including the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award and was invited to take part in photo projects in the Galápagos Islands and other far-flung locations. Despite his renown, however, he maintained a perspective that helped him balance life among family, friends, and work.

A grizzly bear hunts migrating salmon atop a waterfall.

Lynn Schooler, whose book The Blue Bear tells the story of his friendship with Hoshino and their adventures in the wild, and Karen Colligan-Taylor, his longtime friend and English translator, recall Hoshino’s kindness and humility. ”He was simple and good-hearted,” explains Schooler. “He empathized with people and would never put his views above the opinions of others.” Colligan-Taylor describes him as having a disarming, boyish sincerity and a comforting openness that put people at ease. Another aspect of Hoshino’s charm was a natural absentmindedness. This has produced an endless volume of “Michio stories” among his friends. “He was so without ego,” says Schooler, “that he was seldom part of his own thoughts.”

Also among his gifts was a talent for listening that let him make friends wherever he ventured. His would extend his attention equally to each person he met, sitting and listening with sincere interest to the stories they had to tell. Hoshino related these tales in essays that feature a huge cast of players, including bush pilots, hunters, biologists, and pioneers, along with wildlife and the dynamic Alaskan landscape. While environmentally aware and conscious of conservation efforts, he saw people not as an intrusion, but as a central aspect of nature. This idea was especially significant in the special interest he took in exploring the cultures and mythology of Alaska’s native inhabitants.

A Legacy of Living

Hoshino’s works are cared for by his wife Naoko, a soft-spoken woman whose love of Alaska complements her husband’s. His photos and writings remain popular in Japan and are used in school textbooks throughout Japan. Hoshino’s affinity for children led him in 1992 to found the Aurora Club to give Japanese urban youths the opportunity to experience the vastly different environment of Alaska, such as by climbing the Ruth Glacier near Mount Denali. Now in its third decade the group continues to be active, in part through the efforts of Hoshino’s close friend Itō Hideaki, who says the club remains dedicated to Hoshino’s conviction that memories of such experiences can enrich and support people in their subsequent lives.

The Aurora Borealis dances across the face of the full moon.

Hoshino encouraged people to follow their passions, just as he had, and sought to inspire with tales of his experiences in the wild. He understood that most people will never see the migration of the caribou or watch a grizzly cub play with its mother; nor, he felt, did they need to. Simply being able to imagine a world of primeval forests, heaving glaciers, and endless plains—where day and night might stretch on for weeks, and seasonal cycles are both familiar and peculiar—would inspire people to dream.

Hoshino considers his surroundings while perched on a fallen log.

In “Mō hitotsu no jikan” (Another Kind of Time), translated in Hoshino’s Alaska by Colligan-Taylor, he writes: “There is no doubt that as we live each second of our lives, another kind of time flows by on its leisurely course. A constant awareness of this parallel time, tucked in some corner of our hearts or minds, can make a vast difference in our perception of life.”

Hoshino’s journey continues, stirring emotions with its depictions of a timeless Arctic.

A caribou wanders past patches of melting snow on the tundra.

Commemorative Exhibit: Hoshino Michio’s Journey

Dates and locations:

August 24–September 5, 2016, Matsuya Ginza, Tokyo

September 15–26, Osaka Takashimaya

September 28–October 10, Kyoto Takashimaya

October 19–30, Yokohama Takashimaya

(Originally written in English by James Singleton of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Hoshino Michio waits for caribou to appear during the seasonal migration. All photographs by Hoshino Michio and provided courtesy of Naoko Hoshino/Hoshino Michio Office.)