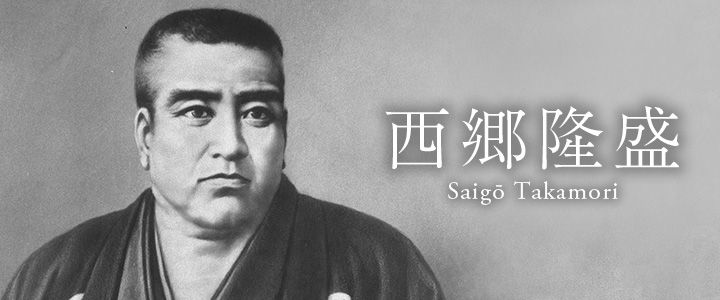

The Life of Japan’s “Last Samurai” Saigō Takamori

History Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Saigō Takamori (1828–1877) is remembered both for his leading role in the Meiji Restoration that overthrew the shogunate in 1868 and for his unsuccessful rebellion against the new government less than a decade later. Although he died a renegade, a government pardon rehabilitated his reputation. At 150 years since the Meiji Restoration, the spotlight is again on the “last samurai.”

Straightforward and Emotional

Saigō’s rise to prominence began in 1854 when he was recruited by Shimazu Nariakira, the progressive daimyō of the Satsuma domain (now Kagoshima Prefecture), to accompany him to the capital of Edo (now Tokyo). As a low-ranking official Saigō had dealt with bridge and road construction projects and rice inspection. However, he caught Nariakira’s attention with a series of memoranda on agricultural administration he submitted to the provincial government. Officially he was employed in Edo as a gardener, but his duties went beyond tending plants. While in the capital, Saigō made contact with major players among the imperial loyalists who opposed the shogunate. The outdoor job offered convenient cover for Nariakira and Saigō to meet and talk, sidestepping the obstacles they would otherwise face due to their wide difference in rank.

A monument marks Saigō Takamori’s birthplace in Kagoshima, Kagoshima Prefecture.

A monument marks Saigō Takamori’s birthplace in Kagoshima, Kagoshima Prefecture.

Saigō rapidly built up a network of loyalists hailing from Mito (now Ibaraki Prefecture) and other domains. He won Nariakira’s trust with his straightforward and emotional nature, and over time the daimyō came to seek the younger man’s opinions. However, the situation began to change from 1857 when Abe Masahiro, a senior councilor in the shogunate who had helped ensure his close friend Nariakira’s succession as Satsuma daimyō, died. Nariakira himself died the following year and power in Satsuma passed to his younger brother Shimazu Hisamitsu who ruled as regent. Meanwhile, conservative politician Ii Naosuke seized effective control of the shogunate, launching major suppression of reformist forces.

Grieving the loss of his protector Nariakira and facing tough political prospects, Saigō was determined to follow his master to the grave but was persuaded by Gesshō, the chief priest of a Kyoto temple, to flee together to Satsuma. Once there, however, they threw themselves into the sea at Kagoshima Bay. Gesshō drowned, but Saigō miraculously survived.

In the Hands of Fate

Over the next five years Saigō endured successive periods of exile on the islands of Amami Ōshima and Okinoerabujima. On Amami, he was allowed a certain amount of freedom and he married a local woman. After a brief reprieve following his return from Amami, though, he was again exiled on a penal island after he angered Hisamitsu with critical words. This period of imprisonment became an opportunity for serious reflection on his life and shaped his character as a thoughtful man of firm principles.

A statue of Saigō Takamori in military uniform in Shiroyama, where the final battle of the Satsuma Rebellion took place.

A statue of Saigō Takamori in military uniform in Shiroyama, where the final battle of the Satsuma Rebellion took place.

Saigō biographer and researcher Iechika Yoshiki argues in his profile of the Satsuma samurai that unlike most people, Saigō fully conquered his fear of death. Having lost many people he loved and respected, including his parents, Nariakira, and Gesshō, he was not terrified by the prospect of dying and may have seen it as a way to reunite with loved ones.

Iechika suggests that Saigō believed heaven had spared his life for a reason and that he would live until completing his divine calling. This philosophy is connected to his famous motto keiten aijin, meaning “Respect heaven and love people.” Saigō’s view was that matters of life and death were above human consideration and should be left entirely to fate.

A portrait of Saigō Takamori beneath his motto “Respect heaven and love people” at Saigō Nanshū Museum in Kagoshima.

A portrait of Saigō Takamori beneath his motto “Respect heaven and love people” at Saigō Nanshū Museum in Kagoshima.

A Bloodless Surrender

In 1864 Saigō reconciled with Hisamitsu and returned to the political center stage in Kyoto as commander of the Satsuma army. After repelling anti-shogunate forces from the Chōshū domain (now Yamaguchi Prefecture) as they attempted to enter the city, he was promoted to the level of high official. The event, known as the Hamaguri Gomon incident, was Saigō’s first experience of battle and leading an army. The same year, he became the chief of staff in the shogunate army sent to punish Chōshū. In 1866, however, Satsuma and Chōshū entered an alliance brokered by Sakamoto Ryōma. Saigō took charge of the opposition forces that would ultimately become soldiers of the new Meiji government.

In January 1868, imperial loyalists led by Satsuma and Chōshū proclaimed the restoration of power from the shōgun to the emperor. Resistance by shogunate supporters sparked the Boshin War later that month. Although the conflict dragged on until the following year, a key victory for the Meiji troops came with the surrender of Edo Castle in the spring of 1868. With the fate of the city and the nation in peril were fighting to break out in Edo, Saigō entered the shogunate stronghold with just a handful of followers, seeking to negotiate. Surrounded by enemy soldiers, he faced the very real prospect of assassination. Discussion and cooperation between Saigō and shogunate leader Katsu Kaishū led to the peaceful handover of the castle, which has been hailed as a “bloodless surrender.”

In Japan, Saigō Takamori, Ōkubo Toshimichi, and Kido Takayoshi are considered the three great figures of the Meiji Restoration. For Iechika, however, Saigō’s Edo Castle success was something the other two members of the trio could never have achieved. He contends that without Saigō, the Meiji Restoration may never have happened, and that because of him, people today view the event favorably. If the movement had resulted in a bloody, all-out civil war, though, it is likely public sentiment would be very different. Although Saigō was not the shrewd politician that Ōkubo was, he had a love and spirit that the other man could not match.

The Shiroyama cave where Saigō is said to have spent his final five days before death.

The Shiroyama cave where Saigō is said to have spent his final five days before death.

A Film Inspiration

In 1871 Saigō joined the Meiji government and in 1873 he became army general. However, he resigned later that year after losing a debate over his advocated backing of a military expedition to Korea. He returned to his home in Kagoshima Prefecture, where he spent his time farming and hunting. In 1877, however, he was prevailed upon to lead an army of disgruntled samurai in the Satsuma Rebellion. Beaten back by government forces in battles across Kyūshū, the army made a final stand at Shiroyama in Kagoshima. Saigō committed suicide after his soldiers were defeated. He was 49.

Saigō Takamori’s grave (center) can be found at Nanshū Cemetery in the city of Kagoshima.

Saigō Takamori’s grave (center) can be found at Nanshū Cemetery in the city of Kagoshima.

Saigō is the likely inspiration for Katsumoto Moritsugu—played by Watanabe Ken—the fictional leader of discontented warriors in the 2003 film The Last Samurai. The movie laments the passing of bushidō (the way of the samurai) through Katsumoto, as observed by Tom Cruise’s Civil War veteran Nathan Algren (the character has no direct historical equivalent).

Saigō’s association with traditional values in a modernizing Japan is why he has been called the “last samurai.” Just 12 years after his failed rebellion, he was pardoned by the Meiji government, and in 1898 a famous statue of Saigō and his dog was erected in Tokyo’s Ueno Park. Nearly a century and a half after his death, he remains a popular historic and cultural icon.

The statue of Saigō Takamori with his dog is a landmark in Ueno Park, Tokyo.

The statue of Saigō Takamori with his dog is a landmark in Ueno Park, Tokyo.

(Originally published in Japanese on April 20, 2018. Reporting and text by Nagasawa Takaaki. Photographs by Kusano Seiichirō. Banner photo courtesy of the National Diet Library.)