Japanese Literature in the Twentieth Century: A Shōwa Retrospective

Shaped by Conflict: Japanese Literature After World War II

Books History Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The second of a series on Japanese literature in the Shōwa era (1926–89) mainly considers books written from 1945 to 1954 (Shōwa 20–29), as the country recovered from and reflected on World War II. It also includes a few later works with strong wartime themes.

No Longer Human by Dazai Osamu

On June 13, 1948, Dazai Osamu (1909–48) jumped into the Tamagawa canal together with his mistress, ending his life by drowning at the age of 38. The previous year his novel The Setting Sun had depicted the postwar fall of Japan’s aristocracy; his death came shortly before the publication of his masterpiece No Longer Human.

“I have lived a life of much shame,” the narrator tells readers at the beginning of No Longer Human, and then, near the end (in the recent translation by Juliet Winters Carpenter), “Now I am neither happy nor unhappy. Everything passes.” These words leave a vivid and powerful impression. Dazai was born as the tenth child of 11 to a major landowner in Tsugaru, Aomori, in northern Japan. Self-destructive by nature, after joining the French department at Tokyo Imperial University (today’s University of Tokyo) he took part in illegal Communist Party activities, then fell into a life of pleasure-seeking before planning a joint suicide at 21 with a Ginza waitress he had only just met. She died, but he survived and lived with the guilt for the rest of his life. After this, he lived with a geisha he called down from Aomori to Tokyo, but fell into despair when she was unfaithful. He made another unsuccessful attempt at suicide, became addicted to a painkiller, and was admitted to a mental institution.

Even so, he showed signs of recovery after entering an arranged marriage at the age of 30, based on a recommendation by his mentor, the writer Ibuse Masuji. He wrote a number of great short works from this time, including “One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji” and “Run, Melos!” but the chaotic situation in Japan after its surrender led Dazai toward destruction again.

In No Longer Human, Dazai makes a confession of his “life of much shame” in the form of a frank memoir. Today, there are few authors who inspire such fervent devotion from their fans and continue to be widely read (Mishima Yukio is another).

Dazai’s works have taken on an eternal life, and No Longer Human was his last will and testament.

- Ningen shikkaku is translated as No Longer Human in separate versions by Juliet Winters Carpenter and Donald Keene and as A Shameful Life by Mark Gibeau.

- Shayō is translated as The Setting Sun in separate versions by Juliet Winters Carpenter and Donald Keene.

- “Fugaku hyakkei” is translated as “One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji” by Ralph McCarthy.

- “Hashire Merosu” is translated as “Run, Melos!” in separate versions by James O’Brien and Ralph McCarthy.

The Inugami Curse by Yokomizo Seishi

Japan’s defeat cast a long shadow over many popular literary genres that found fresh vigor in the postwar era. The Inugami Curse by Yokomizo Seishi (1902–81), which has become a classic in the mystery genre and been adapted many times, takes inspiration from tragedies of demobilized soldiers returning home.

The Inugami Curse is part of a popular series about the great detective Kindaichi Kōsuke, coming after The Honjin Murders, Death on Gokumon Island, and The Village of Eight Graves. Set in a fictional city in Nagano Prefecture after World War II, the novel centers on the battle among the assembled relatives of the Inugami clan over the huge estate of the late, wealthy patriarch Inugami Sahei.

His will states that whichever of his three grandsons marries Tamayo, the beautiful granddaughter of his great benefactor, will inherit the estate. The oldest, Sukekiyo, has returned from fighting in Burma; due to a terrible injury, he wears an eerie rubber mask. There are also inheritance rights for Sahei’s mysterious illegitimate child, whose whereabouts are unknown after demobilization.

A series of bizarre murders ensues. The drama reaches its height as Kindaichi solves a cunning trick and approaches a solution, but the tragedy that assails the Inugami clan is the war itself. The author writes of how the prewar pride and sense of responsibility had been lost, and Sukekiyo laments his ignorance of the great transformation in the feelings of people who remained in Japan. The collapse of the values that the returning soldiers believed in leaves them at the mercy of fate.

- Inugamike no ichizoku is translated as The Inugami Curse by Yumiko Yamazaki.

- Honjin satsujin jiken is translated as The Honjin Murders by Louise Heal Kawai.

- Gokumontō is translated as Death on Gokumon Island by Louise Heal Kawai.

- Yatsuhakamura is translated as The Village of Eight Graves by Bryan Karetnyk.

Fires on the Plain by Ōoka Shōhei

The author Ōoka Shōhei (1909–88) was described by his friend Shiroyama Saburō (who appears later in this article) as having been a soldier from start to finish, saying that “he spent his whole life grinding his teeth at the enormity of the things that he’d lost and that had been taken from him, while also hating those things.”

After studying French literature at Kyoto Imperial University, Ōoka began his working career. In 1944, however, he was drafted and dispatched to the Philippines, where he was taken prisoner the following year by US forces and sent to a prisoner of war camp on the island of Leyte. It was a miracle that he survived such a deadly battleground.

When the war was over Ōoka became an author, recording his own experiences in Taken Captive: A Japanese POW’s Story, and writing the novel Fires on the Plain, a book of mourning, which depicts the precarious existence of individual soldiers living on in the Philippines after the defeat of Japanese forces. It is set on Leyte in the last stages of the war. At a time when weapons, ammunition, and food supplies have run out, the protagonist Private Tamura, who must also contend with resurgent tuberculosis, is told by his squad leader to blow himself up with a hand grenade like a true imperial soldier.

In one scene at a crude field hospital, wounded soldiers who have lost all desire to fight can only wait with empty stomachs for death. Relentless bombardment by US forces, however, sends them running for the hills. In the distance, smoke rises.

As Tamura wanders through the war zone, he repeatedly sights mysterious fires. An abandoned corpse is missing flesh from its buttocks. When his starvation reaches its extreme, Tamura eats “monkey meat” offered by a fellow soldier. Is it really from a monkey or from a human?

Ōoka presents the tragedy of a soldier abandoned by his nation under the purported ideals of “loyalty to the emperor and love of country.” The author was later recommended as a member of the Japan Art Academy, but declined to join, maintaining his anti-establishment thinking.

- Nobi is translated as Fires on the Plain by Ivan Morris.

- Furyoki is translated as Taken Captive: A Japanese POW’s Story by Wayne P. Lammers.

Twenty-Four Eyes by Tsuboi Sakae

Twenty-Four Eyes by Tsuboi Sakae (1899–1967) is an antiwar novel about the obscure ordinary people whose lives were overturned by the conflict. It is set in a small fishing village by the Seto Inland Sea, and vividly portrays the heartwarming relationships between a young woman called Ōishi Hisako, newly graduated from a teacher’s college at the beginning of the story, and her initial class of 12 first-grade children.

The events of the novel span from 1928 to 1946, with the peaceful life of the village in the first half disturbed by gathering war clouds. Ōishi’s naive doubts, expressed when a colleague is accused of being a communist, lead to herself falling under suspicion.

When the children reach sixth grade, they start to think of the future. Influenced by the atmosphere of the day, the boys talk of becoming soldiers. While she cannot openly oppose them, Ōishi is troubled, losing faith in education and resigning her job. She marries a sailor and has three children, but her husband is killed in the war.

The writer asks why people give birth to, love, and raise children if all that awaits them is war. Many of the children in the story, portrayed with such individuality, face harsh destinies, including death in battle.

Readers are likely to be in tears when Ōishi returns to teaching in middle age, after the war is over, and meets again with the survivors of her first class. Tsuboi was encouraged by her husband, a literary scholar, to start writing children’s books in the 1920s. A 1954 film adaptation of Twenty-Four Eyes, directed by Kinoshita Keisuke and starring Takamine Hideko, became a major hit, helping to establish the classic status of Tsuboi’s book.

- Nijūshi no hitomi is translated as Twenty-Four Eyes by Akira Miura.

Black Rain by Ibuse Masuji

Although not written in the immediate aftermath of the war, it is impossible to leave out Black Rain from a selection of World War II literature. While many books have taken the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as a theme, this story stands out as a masterpiece.

The author Ibuse Masuji (1898–1993) was born in Fukuyama, Hiroshima Prefecture, so the hibakusha victims of the bombing were a familiar presence. Before the war, he wrote one of his most famous stories, “Salamander,” in 1929. He also won the Naoki Prize in 1937 for John Manjirō: A Castaway’s Chronicle, about a fisherman who became one of the first Japanese people to go to the United States. He was over 40 years old when he was drafted into the army in 1941 and sent to Japanese-occupied Singapore. After he returned one year later, he lived in his hometown until the end of the war.

The main characters of Black Rain are Hiroshima residents Shizuma Shigematsu, his wife Shigeko, and their niece Yasuko, who lives with them. At the time of the bombing, Shigematsu is at the station and suffers burns to his face. He is diagnosed as suffering from radiation sickness and begins to experience symptoms like fatigue and hair loss. Shigeko was at home and Yasuko working at a factory outside the city, so neither were injured by the blast.

Four years after the war, they live in Shigematsu’s home village, far from the center of the city, but the people there spread rumors that Yasuko suffers from radiation sickness and keep their distance. One day, there is talk of a possible husband for her, but the matchmaker wants to know of her movements since the bombing took place.

The Genbaku (A-Bomb) Dome in Hiroshima in 1945. (© Jiji)

Shigematsu and Yasuko write a diary every day. Shigematsu copies past entries from his diary in an effort to disprove rumors to the matchmaker. Ibuse’s presentation of their peaceful daily life together with diary entries reconstructs in detail the tragedy of the atomic bombing.

Disaster follows as Yasuko, once healthy, starts to show signs of radiation sickness, caused by contaminated “black rain” that fell on her after the bombing.

A sudden shattering of everyday existence changes the lives of the characters. Rather than shouting about the inhumanity of atomic weapons, Ibuse depicts the reality of the devastation through simple descriptions, and his superb ability brings the hellish event in front of readers’ eyes.

- “Sanshōuo” is translated as “Salamander” by John Bester.

- Jon Manjirō hyōryūki is translated as John Manjirō: A Castaway’s Chronicle by Anthony Liman and David Aylward.

- Kuroi ame is translated as Black Rain by John Bester.

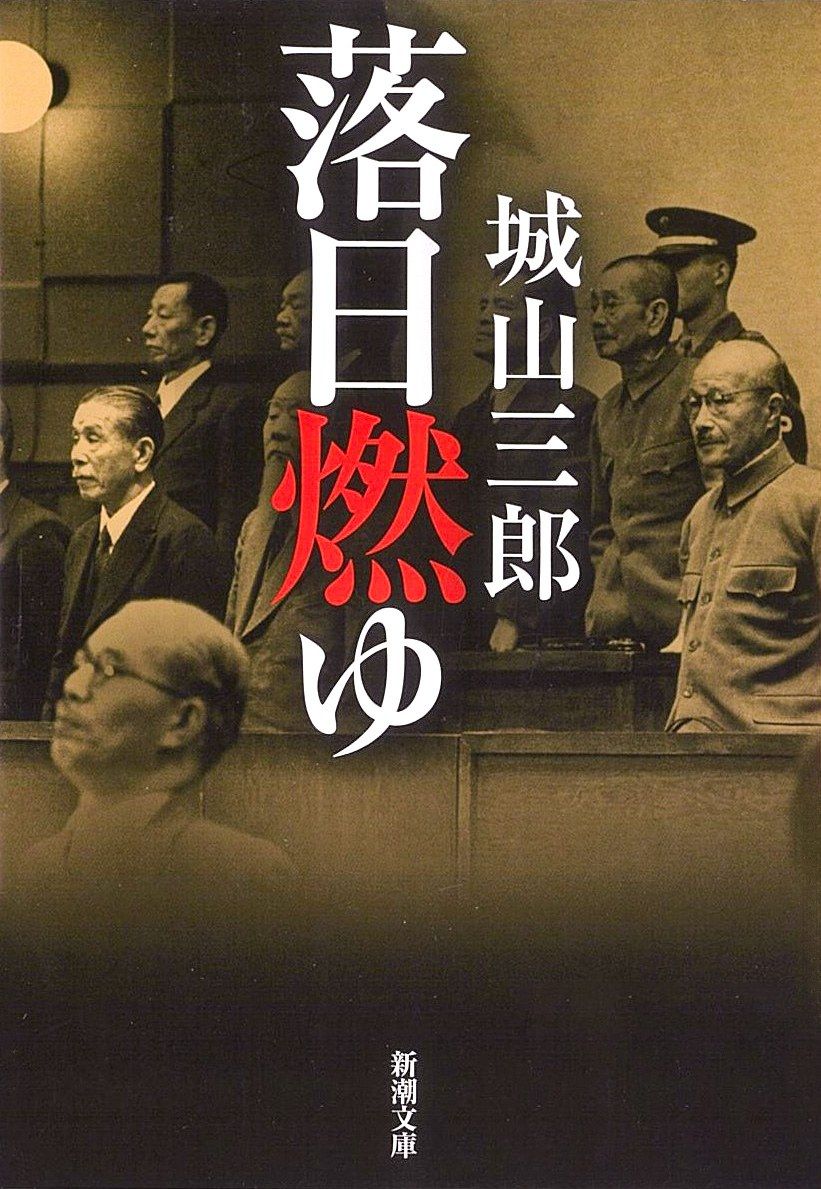

War Criminal: The Life and Death of Hirota Koki by Shiroyama Saburō

A Japanese edition of Rakujitsu moyu (War Criminal: The Life and Death of Hirota Koki) by Shiroyama Saburō. (© Shinchōsha)

One final book I would like to introduce is War Criminal: The Life and Death of Hirota Koki by Shiroyama Saburō (1927–2007), who was known for his historical novels. This tackles the life of Hirota Kōki, who was the only civilian to be executed as a Class A war criminal in the Tokyo Trials organized by Allied powers, and it questions the responsibility of wartime leaders.

Shiroyama volunteered to join the Imperial Navy when he was a college student and was undergoing training in a tokkōtai special attack unit (often called the kamikaze) when the war ended. His question of what the leaders had been thinking was a motivation for him to write. He saw Hirota as one of the men in suits who had reluctantly become entangled in the war machine.

Hirota served as prime minister and foreign minister in the 1930s, and did his best to stop Japan becoming embroiled in conflict, but could not stand up to the pressure of the military. He made no defense of himself at the Tokyo Trials and was sentenced to death by hanging. His family respected his wishes and also said nothing.

Shiroyama had difficulties gathering information, but won assistance from Ōoka Shōhei, who was good friends since school days with Hirota’s eldest son. With Ōoka’s persuasive words, the family talked to Shiroyama. In particular Hirota’s third son, who had acted as his father’s secretary when he was prime minister, provided some new stories that were not previously known. This detailed research provided the basis for Shiroyama’s novel.

- Rakujitsu moyu is translated as War Criminal: The Life and Death of Hirota Koki by John Bester.

Selected Japanese Literature (1945–54) and Other Books Related to World War II

- “Discourse on Decadence” by Sakaguchi Ango, translated by Seiji M. Lippit from “Darakuron” (1946)

- The Setting Sun by Dazai Osamu, translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter from Shayō (1947)

- No Longer Human by Dazai Osamu, translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter from Ningen shikkaku (1948)

- Taken Captive: A Japanese POW’s Story by Ōoka Shōhei, translated by Wayne P. Lammers from Furyoki (1948)

- The Inugami Curse by Yokomizo Seishi, translated by Yumiko Yamazaki from Inugamike no ichizoku (1951)

- Fires on the Plain by Ōoka Shōhei, translated by Ivan Morris from Nobi (1951)

- Twenty-Four Eyes by Tsuboi Sakae, translated by Akira Miura from Nijūshi no hitomi (1952)

- Ningen no jōken (The Human Condition) by Gomikawa Junpei (no English translation) (1958)

- Black Rain by Ibuse Masuji, translated by John Bester from Kuroi ame (1965)

- War Criminal: The Life and Death of Hirota Koki by Shiroyama Saburō, translated by John Bester from Rakujitsu moyu (1974)

Note that some works have multiple translations, but only one is given for each in this list.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 2, 2025. Banner photo: From left, Ibuse Masuji, Dazai Osamu, and Ōoka Shōhei. All © Jiji.)