Japanese Workers Struggle to Take Time Off

Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan is known around the world for the phenomenon of karōshi, or “death by overwork.” The physical or mental demands of excessive overtime and insufficient rest can lead to employees passing away from heart attacks and strokes or taking their own lives. With this in mind, how do Japanese people feel about taking days off?

Employees Not Getting the Days Off They Want

The three main vacation periods in Japan are at New Year, in mid-August around the time of the Obon festival, and when a string of national holidays come together in Golden Week from the end of April to the start of May.

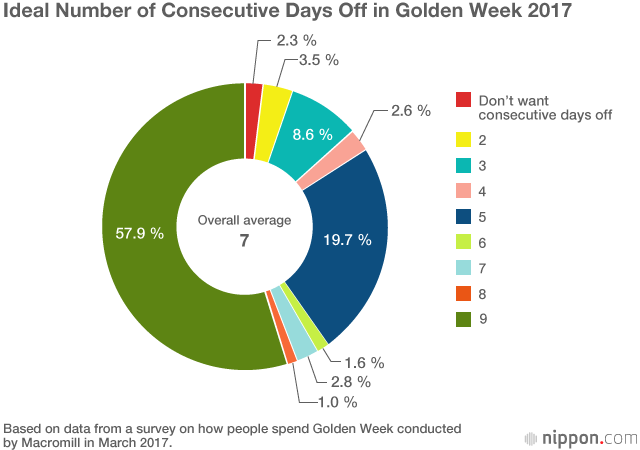

Nearly 60% of employees aged from their twenties to their fifties said they would ideally take nine consecutive days off for Golden Week in a survey conducted in March 2017 by the online survey firm Macromill.

Some respondents wished for no consecutive days off at all, or only a few, bringing the overall average of desired consecutive vacation down to seven days. However, when it came to how many days respondents actually took off, the most common response was only five.

Another Macromill survey found that 53.2 % of employees wished for between 7 and 13 days of summer vacation. In fact, the average number of days taken during this season came to 6.2, or less than half of the upper limit of the desired range.

Japan Worst for Taking Paid Leave

Workers in Japan were entitled to an average of 18.1 days paid vacation from their companies in 2016, according to the General Survey on Working Conditions published by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in February 2017. Yet on average they only actually took 8.8 days, or 48.7% of their total allowance. They gave many reasons why it was hard to use their allowance, such as that “it feels awkward taking days off when others in the office don’t,” “the atmosphere makes it difficult,” “nobody else can do my job,” “duties are not well-defined or quantified, so if I’m away the department’s work doesn’t get done,” and “preparing work so that others can do it is a hassle.” These obstacles lead to the gulf between the vacation ideal and reality.

Expedia named Japan as the worst place for taking paid leave in both 2016 and 2017, based on a survey of workers in 30 countries. These results seem to match those from the Indeed Job Happiness Index 2016, which ranked 35 countries and found that Japanese workers were least satisfied.

Top 10 Countries for Job Unhappiness

| 1 | Japan |

| 2 | Germany |

| 3 | South Africa |

| 4 | France |

| 5 | Poland |

| 6 | Malaysia |

| 7 | Austria |

| 8 | Singapore |

| 9 | India |

| 10 | China |

Source: Indeed Job Happiness Index 2016

Indeed’s index also identifies the elements of job happiness. Work-life balance comes in first place, ahead of such factors as job security and compensation, as employees are most keen to draw a clear line between their jobs and private lives. These results strongly imply that it is the inability to take time off for personal responsibilities and pleasures that causes such dissatisfaction in the Japanese workforce.

Ranking the Elements of Job Happiness

| 1 | Work-life balance |

| 2 | Management |

| 3 | Culture |

| 4 | Job security and advancement |

| 5 | Compensation and benefits |

Source: Indeed Job Happiness Index 2016

Work-Life Balance Is Key

As Japan’s society ages, its working population is steadily shrinking. Saitō Tarō of the NLI Research Institute predicts that the working population will drop from nearly 67 million in 2016 to 62 million in 2026, which is equivalent to a 0.7% drop each year.

Meanwhile, the number of employees caring for aging parents, or for both parents and children, is set to rise. There will also be more workers suffering from cancer or other serious illness who cannot work full-time, but need to earn money to pay for their treatment. And even while the working population slides, some groups are still not getting the opportunity to reach their full potential as employees, such as women with small children and the elderly.

To encourage entry into the workforce and foster talented and enthusiastic employees, there is an urgent need to create workplace environments where taking time off is not discouraged. Seven & I Holdings is one company working on this issue with an initiative whereby whole departments can take vacation days simultaneously to sidestep the problem of feeling obligation to colleagues. The MHLW also reports that 16.8% of companies now encourage taking paid leave by the hour rather than the day. Although not yet a widespread practice, this is a start.

Rather than the traditional system, which places high value on devoted workers who never take time off, “We’re entering an era in which workers are appreciated for the thought they put into their jobs, their level of productivity, and their true qualities,” says Habu Sachiko, who runs the Nikkei Dual website for working parents. She believes that taking paid vacation to make the most of personal life leads to greater productivity and job satisfaction. This virtuous circle has positive effects for all workers—not only those who have caring responsibilities or other reasons for needing flexibility.

Renewing Social Ties Outside Work

When Macromill asked Japanese workers what they most wanted to do during their summer vacation, the top answers were to “relax at home,” “spend time with the family,” and “visit graves.” In Japan, it is traditional for relatives to gather during the Obon period and make offerings at the graves of ancestors. Local festivals and other activities are also a chance to renew interpersonal and community ties. If employees cannot take time off, they miss out on building and maintaining social relationships.

Both work and rest are essential for people living in society. Time spent away from one’s job is just as important as that spent working, not something to be seen simply as a chance to recuperate for the purpose of working again. This is not, however, sufficiently appreciated in Japan. Considering the importance of vacations can inspire reform of both work and life in general. It is time Japan seriously reflected on its companies’ attitudes to time off.

(Originally written in Japanese by Takagi Kyōko of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Commuters walk through the concourse at Tokyo’s Shinagawa Station on the way to work. Courtesy David Pursehouse.)