Tokyo’s Successful Olympic Campaign and the Prospects for Lasting Returns

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Winning Bid

So Tokyo has finally come out on top in the competition to host the 2020 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games. In part, of course, this is a credit to the hard work of the bid committee, which clearly learned the right lessons from the city’s unsuccessful bid to host the 2016 games. To an ever greater extent, though, the decision was the result of the problems that undermined the efforts of all the other final candidates.

Istanbul, poised to become the first city in the Islamic world to host the Olympics, was the early favorite, but violent confrontations between government forces and demonstrators there in June, along with the civil war in nearby Syria, tarnished its prospects. The bid also failed to present any clear solution to Istanbul’s chronic traffic problem. Although this problem was mentioned specifically in the evaluation committee’s report, the bid failed to dispel concerns about the city’s transportation infrastructure.

For a long time Madrid seemed to be lagging behind the competition, reeling from the impact of the European financial crisis and beset with high unemployment and massive public demonstrations. But the city launched a furious comeback just before the general session of the International Olympic Committee around the time of the athletics World Championships in August, enlisting Spain’s Prince Felipe to conduct some high-level diplomacy. However, the Madrid campaign was marred by excessive zeal. The IOC was distinctly unhappy when the names and photographs of 51 of its members, alleged to be supporters of Madrid’s bid, appeared on the front page of a Spanish newspaper. This move, coming just before the final ballot, clearly cost Madrid votes.

What about Tokyo? For a long time during the campaign the people promoting Tokyo’s bid were hard-pressed to come up with a compelling reason why the Olympics should come back to Japan’s capital. There was little question that the city had the necessary infrastructure and funding—but Tokyo’s main edge over the competition may have been simply that it presented fewer obvious drawbacks than the others. The assessment was that Tokyo, with its safe and reliable environment—strongly emphasized during the latter stages of the campaign—was actually capable of hosting the Olympics. The question whether the region’s water might be contaminated by radioactive leaks from the crippled reactor in Fukushima was left unresolved. In essence the IOC voted for the promise of a safe and secure Japan seven years hence, imposing a heavy obligation on Japan to make good on this promise.

A New Model

Since World War II only two cities have been chosen to host the summer Olympics twice: London (1948 and 2012) and now Tokyo, which previously hosted the games in 1964. The 1964 Olympics were preceded by a massive urban renovation effort that cost a trillion yen and added national-level infrastructure including the Tōkaidō bullet train, the Tokyo Metropolitan Expressway system, and the Haneda Airport monorail. No such grand-scale undertaking will be needed to prepare the city for the 2020 games. What is needed instead is a new model that takes into account the lessons and legacy of Tokyo’s first Olympic experience. The best model will be one that incorporates concern for the environment and the urban landscape and seeks to establish Tokyo as a sustainable destination for international tourism.

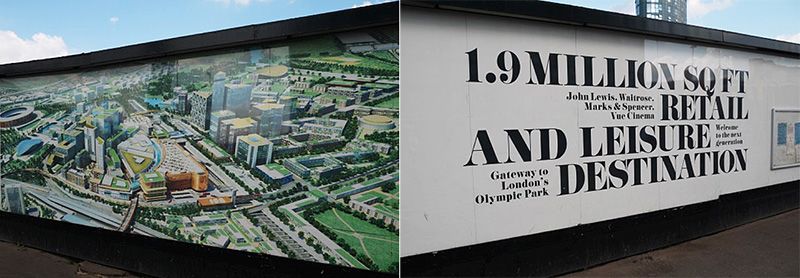

Tokyo has no slum districts or abandoned industrial areas in urgent need of redevelopment. There is no need for a major urban renewal initiative like the one that led to the construction of a gigantic shopping mall in the East End of London before the 2012 Olympics. Tokyo is a well-developed city with most of the necessary infrastructure already in place. It is therefore unlikely that we will see any large-scale public works projects other than those directly related to the Olympics, such as building a new national stadium and the Olympic Village where the athletes and their hangers-on will stay during the games.

It takes a lot of work to run a mature city, though. That work should include moving power lines underground and removing utility poles to improve the landscape. Work also needs to be done to maintain the expressways and other infrastructure to head off deterioration and ensure safety.

Tokyo’s successful bid provides an ideal opportunity for reigniting the debate on city planning, a topic that has languished in the past for want of clear objectives. The opening of the games seven years from now should be treated as a deadline for efforts aimed at further innovation.

The site of a massive shopping mall project in East London, part of a redevelopment effort carried out in preparation for the 2012 Olympics. (Photo by the author.)

The site of a massive shopping mall project in East London, part of a redevelopment effort carried out in preparation for the 2012 Olympics. (Photo by the author.)

Renewal as an Engine for Tourism

What sort of city should Tokyo aim to be? As one point of reference, let’s consider the example of Barcelona. In the lead-up to the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, the city embarked on a campaign to transform itself from a somber municipality steeped in medieval history to a capital of international tourism, with remarkable results. In 1990, based on figures from hospitality establishments, 3.8 million tourists visited Barcelona; by 2000 that number had risen to 7.78 million. There was a sharp increase in foreign tourists, who made up 48.8% visitors to the city in 1990 and 68.7% in 2000. In fact, Barcelona attracted new visitors faster than any other city in Europe. This success gave rise to a new approach to urban renewal that became known as the “Barcelona model.”

Tokyo needs to make similar use of this opportunity to develop a plan for itself and create a new Olympic legacy. Right now the most eagerly anticipated Olympic dividend is a reinvigorated tourism industry. Doubtless many foreign visitors will be drawn to Tokyo for the games. Although Tokyo functions well as a business center, however, it has little to offer in the way of historical sites and tourist attractions. Until recently, tourism was felt to be surplus to requirements.

According to the market research firm Euromonitor International, 3.82 million foreign tourists visited Tokyo in 2010. This is a very low figure when compared to the equivalents for other major cities: 19.97 million for Hong Kong, 14.71 million for London, and 8.18 million for Paris. A Tokyo metropolitan government study carried out in fiscal 2012 found that 35.3% of foreign visitors came to Tokyo on business and 45.1% came for tourism. The most popular destinations, according to the survey, were upscale entertainment districts like Ginza, Shibuya, and Shinjuku, where visitors can enjoy shopping, strolling, and eating Japanese food.

Nationwide Sports Tourism

Holding the 2020 Olympics is likely raise Tokyo’s profile and boost tourism. There are two approaches that can be taken to bring more foreign visitors to Tokyo. The first is to make Tokyo itself more attractive by creating new resources for tourism there. The second is to promote Japan as a whole and highlight Tokyo’s appeal as a gateway. In closing, I want to offer one proposal for each of these approaches.

(1) Old Tokyo Renewed, with More Sporting Events

A good first step in creating new resources for tourism would be to restore part of the historical city. This could be done by rebuilding Edo Castle and replacing the eyesore of an expressway that currently mars Nihonbashi Bridge with a less unsightly underground tunnel. Another effective approach might be to open casinos and provide berths for big cruise ships. Plans for these have already been approved.

In addition to such bricks-and-mortar projects, the city also needs to create and promote sporting events capable of drawing visitors from other countries. Given Tokyo’s dearth of historical tourist attractions, the city’s status as successful Olympic host city is crucial. Japan should look to use this status to cement Tokyo’s reputation as a global capital of athletic competition. To achieve this, I propose establishing a Tokyo sports commission to provide an organizational framework for mobilizing people through sports.

(2) Arrive in Tokyo, Visit Japan

The second proposal centers on the idea of promoting sports tourism. This would be a Japan-wide program, with Tokyo as the gateway.

Japan has a wealth of natural resources capable of attracting sports tourism: powder snow in Hokkaido, coral reefs in Okinawa, forests covering more than 60% of the country, mountains, and a lengthy coastline—a highly diverse, world-class array of resources for outdoor sports. With time, low-cost airlines will provide potential visitors with greater mobility. In the age of smartphones and instant updates, people can find the information they need more quickly than ever before.

These developments should make it easier to attract sports tourists to Japan, especially from other countries in Asia. Building a direct railway link between Narita, Tokyo’s main international airport, and Haneda, its domestic hub, would make travel much easier for foreign visitors.

(Originally published in Japanese on October 1, 2013. Banner photo: Tokyo Olympics boosters celebrating the winning bid. Photo courtesy of Nikkan Sports/Aflo.)