New Organization Takes On Unreasonable Rules in Japan’s Schools

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

In October 2017, a high school student sued the Osaka Prefectural Government for causing mental distress after her high school made repeated demands that she dye her naturally brown hair black. The court case made international headlines, putting the country’s unreasonable school rules under the spotlight.

The school in question forbids students to dye or bleach their hair. For this reason, the girl’s mother went to the trouble of notifying the school in advance about her daughter’s natural hair color asking for consideration of the girl’s circumstances. Despite this, school faculty told the student on several occasions to dye her hair black, frequently instructing her to repeat the treatment because the coloring was uneven or not black enough. She was also barred from the school festival and class trips. Ultimately, she was told that if she did not dye her hair properly, then she should not come to school, after which she stopped attending. This was a case of bullying where the perpetrator was the school itself.

Rules Getting Stricter

The thinking behind the implementation seems bizarre, but the Osaka school is certainly not the only educational institution with unreasonable rules. The incident sparked the formation of a new group—the Burakku Kōsoku o Nakusō Purojekuto (Project to Eliminate “Black” School Rules; the color in Japanese is often used to describe negative entities, such as the burakku kigyō, or “black employers,” that exploit their workers unfairly)—which conducts surveys to bring unreasonable school rules to light and seeks to do away with them. The group’s members come mainly from nongovernmental organizations and focus on issues like bullying.

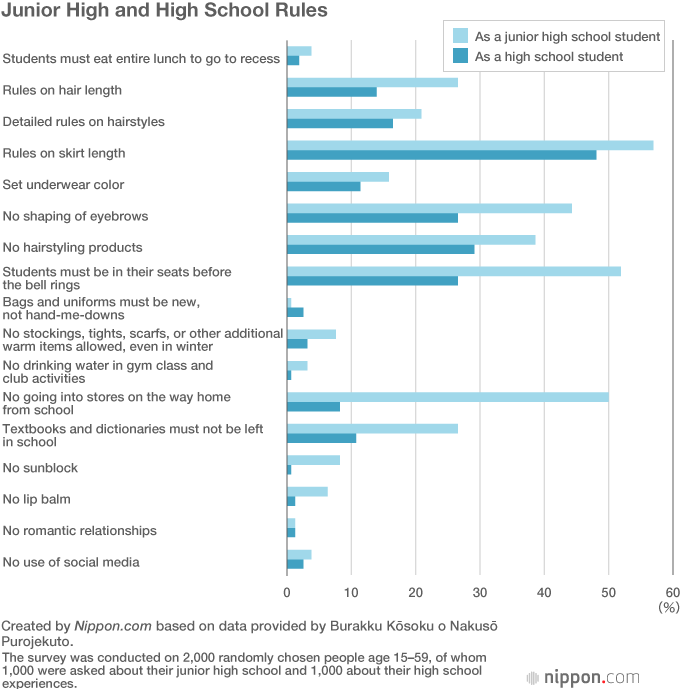

A survey the group conducted in February 2018 fielded data from 2,000 respondents ranging from high school students to adults in their fifties. It aimed to trace changes in rules at junior high and high schools over the decades. As expected, the generation that went through education in the late 1970s and 1980s—when violence, bullying, and other forms of unruly behavior in schools became social issues—experienced particularly strict rules. A more relaxed period followed, but recently rules have tightened up again in such areas as hairstyles and lengths of skirts. Schools have introduced new regulations stipulating everything down to the color of students’ underwear and placing the shaping of eyebrows and use of hairstyling products off limits. Some even disallow health-related items like sunblock and lip balm. There are also many reports of male teachers conducting checks on female students’ skirt lengths and underwear, thus enabling rampant sexual harassment in the name of discipline.

Sunaga Yūji is one of the founders of the project and the vice president of an antibullying organization. He says that when the project asked on its website for examples of unreasonable rules, there were more than 150 responses. “A lot of the people we heard from were venting feelings long held painfully inside, and there were some emotional accounts from more than 30 years ago. I could sense their anger and exasperation.”

Stress for Both Students and Teachers

Sunaga explains that the problem is not simply that schools are imposing irrational rules. “There are cases of teachers using the rules as the basis for unwarranted discipline, like corporal punishment, or going beyond them in what they ask of students,” he says. “This is highly stressful for the children.”

For example, staff members may make whole classes collectively responsible for individual infractions or give students a tongue-lashing in front of their peers. Children learn from these excessive experiences that rules must be obeyed absolutely, leading to them monitoring each other. They will tend to instinctive caution to ensure they do not come close to stepping over the line, while at the same time shunning the minority of rule-breakers. This can be the cause of bullying or create such a level of tension that those students who cannot stand the daily stress stop attending school.

A female survey respondent said, “I was always on edge, worrying about breaking any of the extensive rules on clothing and so on. When the oversensitivity to rules led to an oppressive atmosphere, with students watching each other, I started skipping school.” A male respondent with a Japanese mother and American father said, “My teachers never said anything about the color of my hair, but as my classmates had had conformity hammered into them, they would keep asking me whether I was breaking the rules. The stress led me to stop attending.”

Yet Sunaga does not think the solution is simply to criticize teachers and schools. As well as students, some teachers contacted the site asking for help. They made comments like, “I tell students to follow the rules, but I can’t explain why because I don’t understand the reasoning behind them.” “I can see the contradictions myself, but it’s the opinions of people who have a voice at staff meetings, like the school head and teacher in charge of discipline, that win through.” “Some teachers who take the students’ side get frozen out.” These illustrate the difficult lot of teaching staff caught between the school bureaucracy and the interests of the students.

Positive Suggestions Needed

Sunaga says, “There’s nothing to gain from further pressing already harried teachers. Rather than just throwing out criticism like ‘The teachers are no good, the schools are no good, the Ministry of Education is no good,’ what we need now are positive suggestions for improvements and possible solutions.”

The project is considering asking schools to disclose their current rules and holding hearings with teachers. “Until now there’s basically been no assessment or verification of the effectiveness of school rules. What is the purpose of rules about hairstyles? Are they achieving the intended educational benefits? If not, changing them may reduce the burden on both those checking and those being checked. We’re not recklessly asking for an end to school rules, but by making evidence-based suggestions, we might be able to open up a new path.”

Sunaga himself did not attend school for two and a half years after being bullied while in the fourth grade of elementary school. Even setting foot outside the house was so stressful that he had difficulty breathing. He recovered from this experience through attending a “free school” run by the nonprofit organization Tokyo Shure and was able to reconnect with society without receiving a traditional education. He became a founder of the antibullying group Sutoppu Ijime Nabi (Guide to Stopping Bullying); as vice president and secretariat head of this group, he interfaces with other organizations and gives speeches around the country. Before antibullying legislation was passed in June 2013, Sunaga actively lobbied lawmakers to ensure that the views of people who had been bullied and their parents or guardians would be incorporated into the bill.

Sunaga Yūji talks about the need to offer students more options.

Sunaga Yūji talks about the need to offer students more options.

“The oppressive atmosphere in Japan is due to the extremely limited options outside of traditional school education,” Sunaga says. “Students are crammed into a curriculum of fixed answers and assessment methods and flattened into homogeneity with draconian rules. But there are other possibilities, and they have the right to be able to get an education elsewhere. And if they do go to school, there are approaches other than simply doing as they’re told or calling for the rules to be abolished.

“There’s a limit to what we can do as a small group. But if anyone wants to make a change, we hope we can work together.”

(Originally published in Japanese on June 5, 2018. Reporting and text by Takagi Kyōko of Nippon.com. Banner photo © Kazpon/Pixta.)