Paper Cranes Bringing Hope to the World

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Paper Cranes from the President

In May 2016, Barack Obama became the first sitting US president to visit Hiroshima, site of the world’s first atomic bombing in 1945. He brought with him four paper cranes that he had folded himself.

Sasaki Masahiro, author of Sadako no senbazuru (Sadako’s Thousand Cranes), was amazed when he heard that the president had made the cranes himself.

“Even though he couldn’t give an apology as President, I think he was delivering a personal message that he was sorry. I sensed from those folded cranes both his humanity and that message.” Obama later donated two more paper cranes to the second atomic bomb target, Nagasaki.

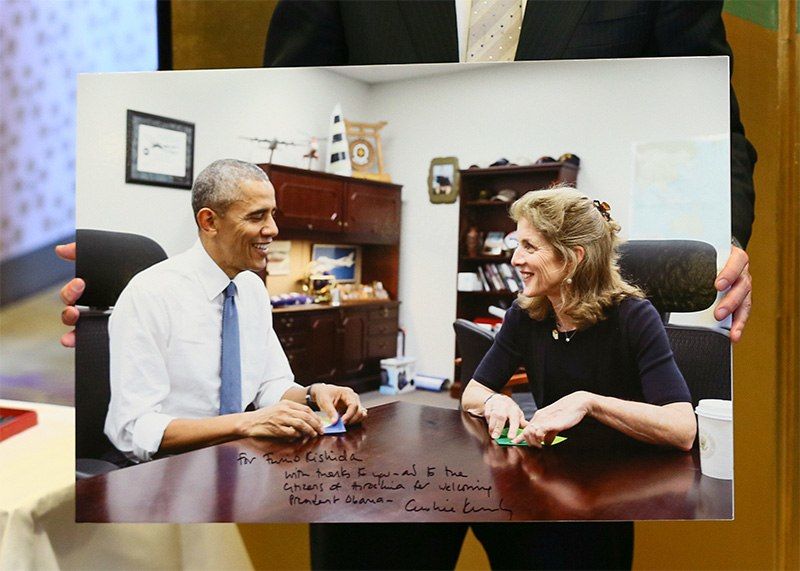

President Barack Obama and Caroline Kennedy, then US ambassador to Japan, folding paper cranes during the President’s historic visit to Hiroshima in 2016.(© Jiji Press)

President Barack Obama and Caroline Kennedy, then US ambassador to Japan, folding paper cranes during the President’s historic visit to Hiroshima in 2016.(© Jiji Press)

Origami, the art of folding paper to make decorative items, is a common indoor entertainment in Japan, and most people learn how to fold an origami crane in their youth. As the crane is a symbol of long life, strings of 1,000 paper cranes, or senbazuru in Japanese, are often offered as a get-well gift expressing hope for a person’s recovery, as a sign of support for natural disaster victims, or encouragement for sports teams.

But paper cranes are starting to become known around the world as a tangible form of prayer for peace or a way to show of support for people facing difficult challenges.

When 12 boys and their soccer coach were trapped in flooded caves in Chiang Rai, Thailand, in June 2018, the classmates of one boy folded 1,000 cranes in three days to pray for the group’s safe return.

Paper Cranes Go Global

Sadako in her first kimono at age 12. (Courtesy of Sasaki Masahiro and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Sadako in her first kimono at age 12. (Courtesy of Sasaki Masahiro and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Behind this global recognition of the power of paper cranes lies the story of Sasaki Masahiro’s younger sister, Sadako. Sadako was just 2 years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on her home town, Hiroshima. She developed leukemia at the age of 12 and died after an eight-month battle with the illness. Sadako was a keen runner, and in the belief that she could recover and return to normal life, she continued to fold from 1,300 to 1,500 paper cranes while in her hospital bed. The Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima’s Peace Park—a figure of a girl with arms outstretched, holding up a golden paper crane—is said to be modeled on her. Some 10 million cranes from around the world are offered here every year. Indeed, the story of Sadako and the thousand cranes may be better known abroad than it is within Japan itself.

In 1956, the Austrian journalist Robert Junk visited Hiroshima and introduced Sadako’s story to the world in his book, Light in the Ruins. Junk, a Holocaust survivor himself, said he was moved by Sadako’s attitude to life, her intelligence, and her consideration for her parents’ feelings. Sadako’s story was later taken up in numerous children’s books and school readers, and has become familiar to children around the world.

The Children’s Peace Monument and booths filled with senbazuru offerings. (© Daniel Rubio)

The Children’s Peace Monument and booths filled with senbazuru offerings. (© Daniel Rubio)

We asked Sadako’s brother, Sasaki Masahiro about the increasing globalization of origami cranes. Sasaki has set up a nonprofit organization in Japan called the Sadako Legacy, and is engaged in peace activities, which include giving talks and using the remaining paper cranes left by Sadako.

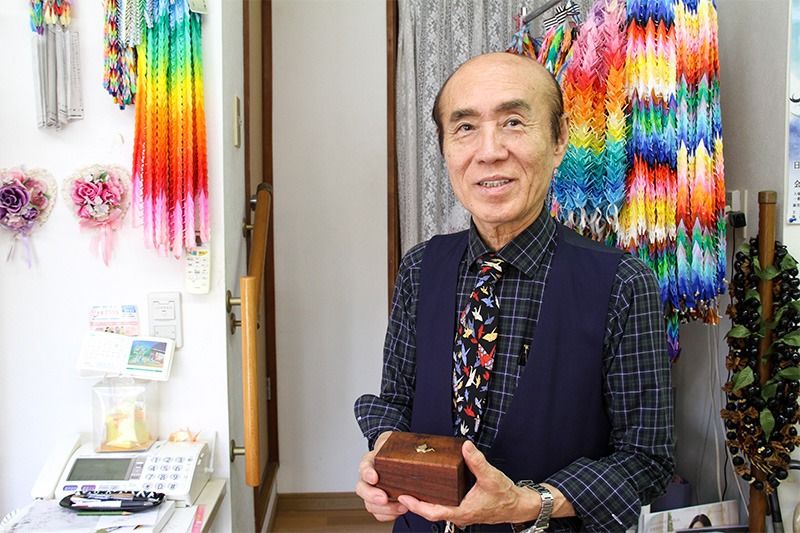

The walls of Sasaki’s Fukuoka Prefecture barber shop are decorated with senbazuru sent to him from all over the world. Even his necktie sports a paper crane motif. (© Doi Emi)

The walls of Sasaki’s Fukuoka Prefecture barber shop are decorated with senbazuru sent to him from all over the world. Even his necktie sports a paper crane motif. (© Doi Emi)

A Paper Crane for Pearl Harbor

A tiny paper crane less than the size of a thumbnail, folded by Sadako herself before her death, is on display at the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center in Hawaii, one of the recipients Sasaki has chosen for the few remaining cranes that his sister made. “I can’t donate one of these if it’s just a one-sided gesture. It won’t mean anything if the recipient doesn’t understand its meaning, or feel a real need for it,” Sasaki explains.

When someone says “No more Hiroshimas” in America, they are likely to hear, “Remember Pearl Harbor” in response. The displays at the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center, established to commemorate the Pearl Harbor bombings that drew the United States into war with Japan, mainly focus on the United States as the target of Japanese aggression. When the Center was considering creating an exhibit to promote peace in 2012, though, one person actively supported the idea of including one of Sadako’s paper cranes in the display.

That person was Clifton Truman Daniel, grandson of former US President Harry S. Truman, the man who ordered the bombing of Hiroshima.

It was in 2004, when Sasaki was visiting the United States for the unveiling of a restored sculpture of Sadako and the thousand cranes in Seattle’s Peace Park, that he first spoke to Daniel over the phone. “I told him that although I was a hibakusha, an atomic bomb victim, I was not speaking as a representative of victims who want to communicate the horror and misery inflicted by the bombings. I said I wanted an opportunity to talk about the fundamental issue of how to eliminate the factors that led to the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the first place. And I wanted to speak to someone with a completely different perspective from my own.” Daniel immediately understood Sasaki’s aim. He noted that he had read a book about Sadako, and that American children learned about her at school. He lent his support for Sasaki’s donation to the Pearl Harbor exhibit.

Cranes Sadako folded on her sickbed, including one in light green paper that she never got to finish. Sadako used wrapping paper and other scraps instead of expensive origami paper, using a needle to craft the smallest thumbnail-sized cranes. (© Doi Emi)

Cranes Sadako folded on her sickbed, including one in light green paper that she never got to finish. Sadako used wrapping paper and other scraps instead of expensive origami paper, using a needle to craft the smallest thumbnail-sized cranes. (© Doi Emi)

It was not until six years later, in September 2010, that Sasaki and Daniel met in person in New York. Daniel said he had always wanted to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but had hesitated out of fear of what might happen if news got out that Harry Truman’s grandson was there. It was after talking to Sasaki that he found the courage to go ahead with the idea.

Daniel finally made the trip to Japan with his wife and three children in August 2012, attending ceremonies in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as listening to the stories of over 40 hibakusha. At a press conference during his visit, Daniel said that he came to explore ways for Japan and the United States to overcome the enmity of the past and work for a better future for the children of both countries.

Clifton Truman Daniel and Ari Beser (at left), grandson of Enola Gay radar specialist Jacob Beser, visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on August 4, 2012. Sasaki Masahiro is just visible at right. (© Aflo/AFP Photo/Kazuhiro Nogi)

Clifton Truman Daniel and Ari Beser (at left), grandson of Enola Gay radar specialist Jacob Beser, visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on August 4, 2012. Sasaki Masahiro is just visible at right. (© Aflo/AFP Photo/Kazuhiro Nogi)

Sadako’s Hope Lives On

Daniel and Sasaki are currently applying to set up a nonprofit organization in the United States, to be called the Paper Cranes Foundation.

In Sasaki’s words, “Hate only ever breeds hate. Hate never breeds love. For us to avoid reliving the horrors of war, first we need to humbly face, and learn about, each other. That means opening our hearts to our counterparts.”

About his sister, Sasaki has this to say: “Sadako was a special child. Even though she knew that she had leukemia, she pretended she didn’t, out of consideration for her family, and fought the fear and pain alone. She tried to overcome her condition by folding paper cranes. She was born with a destiny.”

Sadako (center, front row) was the fastest runner in her school. (Courtesy of Sasaki Masahiro and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Sadako (center, front row) was the fastest runner in her school. (Courtesy of Sasaki Masahiro and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)

Now, 60 years after Sadako’s death, people in Japan—and all over the world—are expressing their hopes for peace and recovery through origami cranes. Japan receives gifts of these birds accompanying international donations to domestic disaster relief efforts; elsewhere around the globe, schoolchildren who have survived tribal and ethnic conflicts fold cranes together in their classrooms.

Sadako’s will to live, never giving up hope as she continued to fold cranes on her sickbed, is being emulated somewhere around the world right now as a pair of hands purposefully fold a paper crane.

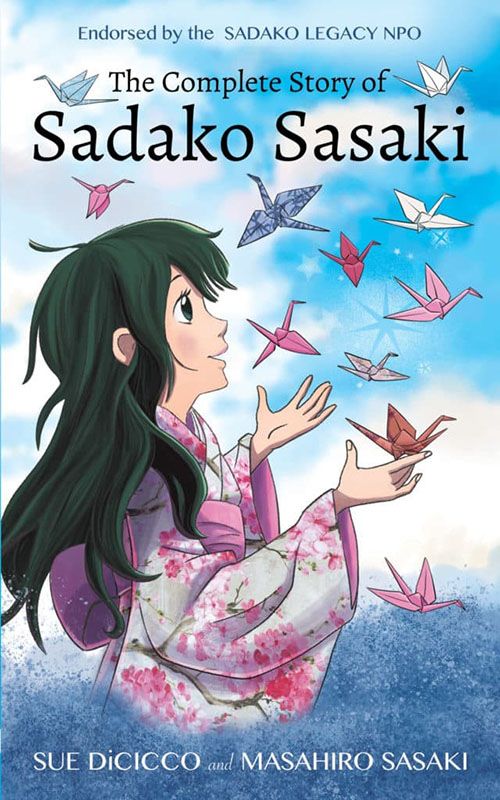

The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki, by Sue DiCicco and Masahiro Sasaki will be published by Armed with the Arts in September 2018.

The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki, by Sue DiCicco and Masahiro Sasaki will be published by Armed with the Arts in September 2018.

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Paper cranes donated by US President Obama in Hiroshima, May 27, 2016. © Jiji Press.)