Japan Struggles to Ward Off a Childless and Aging Society

Family Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Japan has a head start on the rest of the world when it comes to its rapidly declining birthrate and aging population. The government’s first serious effort to tackle the problems arising from this situation was in 1994, when the ministers of education, health and welfare, labor, and construction combined their resources to implement the Angel Plan, an initiative to provide better childcare support for working parents. Successive national and local administrations since then have continued the effort through additional measures to increase the number of daycare facilities, for example, but in major urban areas there is still a backlog of children waiting for openings.

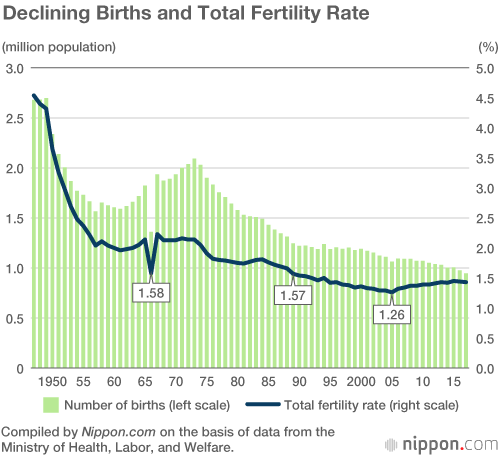

In the meantime, the birthrate continues to decline at an ever-more rapid clip. Daycare facilities in outlying regions are struggling as their enrollments drop, and some are closing down completely. In another ominous sign, for the past 15 years an average of around 500 elementary and junior high schools have been closing every year. The number of births per year dropped to under 1 million for the first time in 2016 and had declined even further to by 2017 to 946,000. There is speculation that the number may fall below 900,000 for 2018. And yet there are still parents unable to enroll their children in daycare facilities in certain areas. The reasons for this are complex and intertwined.

Dual Incomes Now the Norm

First, there are more women taking up the slack in a shrinking labor force, and a growing number of these women are continuing to work after giving birth or seeking new employment while their children are still small.

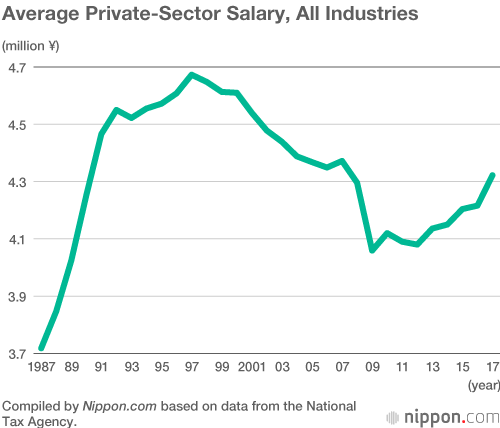

Second, while household income is believed to have hit bottom, it is still not back to the level of the 1990s. In many cases, both parents need to work to support their children.

Third, women are getting married and having children at later ages. If they take time off to care for their family, they will be in their late thirties or forties by the time they can re-enter the labor force, making it difficult for them to find employment. As has already been noted, this is another reason women are choosing to return to work while their children are still small.

New Facilities Spark Still More Demand

Fourth, opening new daycare facilities stimulates demand that can outstrip even the newly available capacity. When a new daycare center opens in a community, parents living there who were debating whether to seek employment are more likely to decide to work when they know there will be a place to care for their children while they are at their job. And with the current labor shortage, anyone who is willing to work can easily do so.

Fifth is the uneven distribution of jobs and people. Young people are leaving rural areas—as well as suburban areas abutting major cities—to move to the more convenient city centers. While the Japanese population as a whole is decreasing, in major metropolitan areas, especially in central Tokyo, it is increasing with the influx of young people. Because of this, even though Tokyo’s total fertility rate is the lowest in the country, the number of children living in the metropolis is increasing.

Another phenomenon is the unevenness of the population decreases. For example, the Kansai region, particularly Osaka Prefecture, is seeing a decline in population overall, but in the city of Osaka, the population is growing so rapidly that the construction of high-rise condominiums can barely keep up. The situation is further aggravated by the high cost of land in the metropolitan areas. This makes it nearly impossible to build new daycare facilities, a failure that can be directly tied to the lack of urban planning.

Sixth is the lack of trained childcare workers—particularly in the central metropolitan areas where jobs for women are plentiful. The work conditions and salaries for professional childcare workers are simply not as attractive as those for the many other kinds of careers available to women. Childcare workers are not paid well, generally have to work long hours, and often have to cope with sick or injured children and difficult parents. Measures have been implemented to raise their salaries, but cases have been reported of daycare facility owners and managers using funds meant to go toward employee salaries for other purposes.

Administrative governments in urban areas are using their relatively flush coffers to pay higher salaries and improve working conditions at public daycare facilities, but it should be noted that this is drawing more young women away from outlying regions to already crowded metropolitan centers, thereby further aggravating the population imbalance.

Finally, childcare workers tend to work long hours because the parents of the children they are caring for are doing the same. Government policies tout the increased employment of women and policies to “revolutionize” employment practices, but work standards remain much the same as when men were the breadwinners and women were expected to be homemakers. Employment conditions that allow for a better work-life balance for both men and women are still the exception rather than the norm.

Are Fulltime Homemakers Keeping Social Security Costs Down?

It wasn’t until the implementation of the Angel Plan that the operation of daycare facilities changed to accommodate the needs of parents working fulltime. Before then, daycare facilities generally closed at 5:00 in the evening and otherwise were out of sync with the reality of the working environment. Working parents were forced to hire babysitters or appeal to their own parents to provide additional care for their children. For many women, continuing to work after giving birth was not a realistic option.

Special measures, such as extended daycare hours and the care of sick children, did not begin to take hold until the first decade of the 2000s. Why did it take so long?

One reason is the success Japan had enjoyed up until then with a division of labor based on gender and a society of single-income households. In 1979, just 15 years before the Angel Plan was drafted, the Liberal Democratic Party published a compilation of studies titled The Japanese Welfare Society, which asserted that it was possible to keep Japanese taxes and welfare costs low because fulltime housewives took on the burden of childcare and the nursing care of elderly parents. The studies also claimed that Japan would go bankrupt if it undertook to build all the daycare facilities that would be needed for women to enter the labor force.

Yet, just 10 years later, in 1989, there was a sharp decline in the birthrate to 1.57, lower even than the 1.58 rate of 1966, the year of the hinoe uma, believed to be an inauspicious zodiac sign under which to be born. Much was made of the so-called “1.57 shock,” but it was not enough to undermine the traditional values of the one-income household and little progress was made in changing work conditions. The Japanese birthrate has continued to decline, hitting a record low of 1.26 in 2005. While there have been sporadic upturns since then, none have been strong enough to reverse the decline. Over a period of three decades, countermeasures to tackle the falling birthrate have been feeble at best, with no effort being expended to undertake the major overhaul that is needed.

Daycare facilities cannot on their own solve the problem of the enrollment backlog of children needing care while their parents work. The issue needs to be tackled by society as a whole; employers, for their part, need to implement major changes that will provide better childcare support for their employees, such as corporate childcare leave programs and more flexible work styles.

A Society Unable to Foster Its Own Children

Japan’s birthrate continues to drop, but the problem of daycare enrollment backlogs remains unsolved. The government’s plan to provide free childcare from fiscal 2019 will stimulate the demand and probably make the backlog worse. Halfway measures meant to attract votes will only serve to aggravate the situation. Allowing unsubsidized and unregulated daycare facilities to be included in the plan to provide free childcare could expose children to unsafe conditions; there are even sporadic stories of children dying in such facilities.

Another reason for the sharp decline in Japan’s birthrate is the growing number of unmarried young people among the children of the baby-boom and post-baby-boom generations. This phenomenon can be traced back to an unstable job market, in which a growing number of struggling companies are opting out of traditional fulltime hiring and instead shifting to limited-term contract and part-time employees. How can young people be expected to marry and raise children when they have no job security and wages are low?

The current labor shortage means more job opportunities for young people, but we tend to forget that the failure over the last two decades to properly address the problems inherent in Japan’s social fabric has come at a high cost for the younger generation, accelerating the crash of the birthrate. Measures to guarantee stable employment and create an environment in which people who wish to do so can marry and have children need to be implemented as soon as possible.

Japan once considered children to be a valuable asset of society, yet somewhere along the way it has lost the tolerance needed to foster future generations. Childcare has come to be considered an individual responsibility—more precisely, a woman’s responsibility—rather than a shared responsibility of society as a whole. With its low birthrate and aging population, Japan is on the verge of morphing into a childless and aging society. The lack of leadership and foresight threatens to plunge the country into an uncertain future.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)