Legends: Japan’s Most Notable Names

Ozawa Seiji: The Self-Made Maestro

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

(Originally posted in July 2018.)

One of the most renowned orchestra conductors of the modern era, Ozawa Seiji was not born into a musical elite. His success in the classical music world springs from his hard work, dynamism, and personal appeal, qualities that have allowed him to reach the pinnacle of his craft.

On January 1, 2002, Ozawa appeared with the Vienna Philharmonic at its New Year Concert, a 60-year-old traditional event televised in over 60 countries around the world. This would be a feather in any conductor’s cap—especially for the first Japanese ever to fill the role—but for Ozawa, it was just one more item to list on an amazing curriculum vitae.

During his career, Ozawa served as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, one of America’s top orchestras, for nearly 30 years. In 2002, the year of his Vienna Philharmonic appearance, he also became the music director of the Vienna State Opera. In addition, he was one of only a handful of conductors to have regularly led the world’s two leading orchestras, the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Philharmonic. Ozawa’s career has truly been spectacular, taking him to heights achieved by few other Japanese in the field of Western musical culture. No other Japanese conductor has come close to his successes.

Not Your Typical Japanese Orchestra Conductor

Ozawa Seiji was born on September 1, 1935, in Mukden, Japanese-occupied Manchuria—present-day Shenyang in the People’s Republic of China. His family’s roots were in Yamanashi Prefecture, where they were poor farmers, but Ozawa’s father Kaisaku, by dint of sheer hard work, became a dentist and set off for Manchuria at the age of 23, opening a practice in Changchun. There he met and married Wakamatsu Sakura, Ozawa’s mother. Kaisaku, an ardent supporter of pan-Asianism and a founding member of the Concordia Association of Manchukuo, later moved the family to Mukden. Seiji, the couple’s third son, owes the first part of his name to Imperial Japanese Army general Itagaki Seishirō, with whom Kaisaku had found favor, and the second part to the high-ranking Kwantung Army officer Ishiwara Kanji. Ozawa Seiji did not set foot on Japanese soil until he was 6 years old.

Ozawa did not start out as part of Japan’s musical elite. His first encounter with music was at the age of 5, when his mother gave him an accordion as a Christmas present, and he only began piano lessons when he was 10. The family had returned to Japan in 1941 and was living in Tachikawa, a western suburb of Tokyo. The home did not have a piano, and when the family was given one by relatives, it took his older brothers three days to haul it from Yokohama to Tachikawa in a handcart.

Ozawa dreamed of becoming a pianist, but his late start put him at a disadvantage. In December 1949, he happened to attend a concert at Tokyo’s Hibiya Kōkaidō hall featuring Leonid Kreutzer conducting the Japan Symphony Orchestra (today the NHK Symphony Orchestra) and playing the piano. This experience opened Ozawa’s eyes to the allure of conducting. At the age of 15, he began studying under the music educator and cellist Saitō Hideo (1902–74), a distant maternal relative.

Fortuitous Encounters

Fate often has a hand in people’s lives, and that was certainly the case for Ozawa. Saitō nurtured many eminent conductors and string players at the Tōhō Gakuen School of Music, and Ozawa looked up to him as a mentor throughout his life.

Another individual Ozawa met in Saitō’s conducting class was Yamamoto Naozumi (1932–2002). Yamamoto was a conductor and also the composer responsible for the theme music of the Otoko wa tsurai yo (It’s Tough Being A Man) film series. Ozawa took his first lessons in conducting from Yamamoto. In 1952, Ozawa began studying at Tōhō Gakuen, which Saitō had been instrumental in founding. He advanced to its junior college in 1955 but eventually started to feel the need to study in Europe to round out his musical education. Yamamoto encouraged Ozawa, saying “Music is like a pyramid. I’ll keep working on broadening its base, so you go to Europe and aim to be the apex.”

And off to Europe he went. Acting decisively as usual, in February 1959, Ozawa, age 23, left for France aboard a freighter, entering the International Besançon Competition for Young Conductors the same year. He had missed the entry deadline, but through the good offices of an American embassy staffer, he entered the competition and came away with the top prize. This was the first step of his brilliant career.

Charles Munch, one of the competition’s judges, recommended Ozawa to the Tanglewood Music Festival organized each summer by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and he participated in 1960. In 1961, he was appointed assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under Leonard Bernstein. He also won a place to study under the Berlin Philharmonic’s Herbert von Karajan. Ozawa thus was privileged to train under the two greatest conductors of the latter half of the twentieth century, something no other young conductor has ever accomplished.

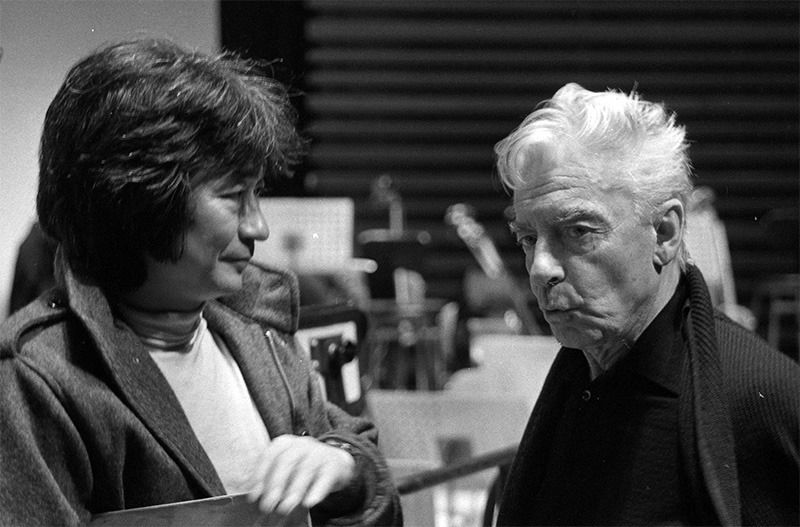

Ozawa Seiji with Herbert von Karajan, music director of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, in 1982. (© Fujifotos/Aflo)

Ozawa Seiji with Herbert von Karajan, music director of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, in 1982. (© Fujifotos/Aflo)

Ozawa and the NHK Symphony Affair

Ozawa was never a natural genius: his success has been the fruit of hard work and continuous study. Those who know him say that he is affable, filled with love for his fellow man, and mindful of duty. Coupled with his dedication to work, these qualities have brought Ozawa numerous fortuitous encounters.

But things did not go so well for him in Japan. Hired to conduct the NHK Symphony Orchestra in 1962 for a six-month term, Ozawa, then aged 27, was boycotted by some of the orchestra’s musicians. Perhaps miffed at the thought of playing under such a young conductor, some members declared that Ozawa was brash or lacked humility and refused to play under him. In a counterprotest, several eminent figures from the theater, literary, and musical worlds—among them Asari Keita, Ishihara Shintarō, Inoue Yasushi, Ōe Kenzaburō, Takemitsu Tōru, Tanikawa Shuntarō, and Mishima Yukio—organized a musical event to hear Ozawa conduct. This was entirely reflective of Ozawa’s drawing power, but after his unpleasant experience with the NHK Symphony, he ultimately gave up on Japan and set his sights on the global stage.

In 1972, while Ozawa was serving as the principal conductor for the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra, Fuji Sankei Group, the orchestra’s sponsor, announced that it was withdrawing support. Hurriedly returning to Japan from the United States, Ozawa made every possible effort to ensure the orchestra’s survival, even appealing directly to the Japanese emperor for support. A recipient of the Japan Art Academy Prize that year, at the award ceremony he let slip that “I am the recipient of this award, but the orchestra I’m working with is in dire straits.” Ultimately, the orchestra, organized as a foundation, was dissolved (it continued its activities as a self-organized group and would later reform as a foundation), and Ozawa, together with Yamamoto Naozumi, formed the New Japan Philharmonic. For decades thereafter, Ozawa conducted this orchestra exclusively when he was in Japan. Yamamoto, leading the New Japan Philharmonic, appeared on television with the orchestra, which Ozawa guest-conducted numerous times.

Reaching the Top

Ozawa began to make his mark on the world stage the next year. In 1963, he was a success at the Ravinia Festival, organized by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, as a last-minute stand-in. He went on to serve as that festival’s music director from 1964 to 1968. He became music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in 1965, a post he held until 1969. In 1966, he conducted at the Salzburg Festival and at regular performances of the Vienna Philharmonic and the Berlin Philharmonic. He served as artistic director of the Tanglewood Festival from 1970 to 2002 and as music director of the San Francisco Symphony from 1970 to 1976. In 1973, he began an unprecedented stint almost 30 years long as music director of the Boston Symphony, over which he presided until 2002.

The year 1979 saw him make his debut at the Opéra in Paris, 1980 at La Scala in Milan, and 1988 at the Vienna State Opera, achieving success at the highest level in the world of opera as well. In 2002 he became music director at the Vienna State Opera, a position he held until 2010. His recordings were also spectacularly successful for classical music. In particular, the CD of his 2002 New Year Concert with the Vienna Philharmonic sold 800,000 copies in Japan and 1 million worldwide. And in 1994, the performance hall built at Tanglewood was named after him.

After his initial rocky period, Ozawa resumed musical activity in Japan. In 1987, he founded the Saitō Kinen Orchestra, composed of former students of Ozawa’s mentor, helping it to develop into a world-class orchestra. In 1990, Ozawa became artistic advisor to the Mito Chamber Orchestra and general director of the Saitō Kinen Festival Matsumoto in 1992 (renamed the Seiji Ozawa Matsumoto Festival in 1994). Under his tenure, the Festival’s offerings became an object of envy for music-lovers everywhere. He led a global chorus on five continents in a simultaneous live performance of the “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at the Nagano Winter Olympics opening ceremony in 1998. In 2000, he established the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy to nurture young musicians.

Music Infused with Dynamism and Charisma

Conductors, who do not personally play an instrument when conducting, are a strange breed of musician, leading a “family” of 100 or so performers who actually play the various instruments. The conductor’s role is to communicate his intentions as to how the music should be played and shape the piece according to his vision. This requires not only knowledge and technique but personal dynamism and charisma as well. Ozawa has impeccable baton technique thanks to Saitō Hideo, who systematized conducting methods in Japan, but his real strength lies in his personal aura, developed through effort and experience.

A revealing episode is indicative of Ozawa’s own charisma. In 2015, Ozawa paid a visit to the New Japan Philharmonic’s long-time tympanist Yamaguchi Kōichi, who lay dying. Family members at his bedside encouraged the barely conscious Yamaguchi to squeeze their hands to show that he was aware of their presence, but he responded with barely perceptible squeeze. When Ozawa addressed him, though, his eyes flew open and he was even able to hold a brief conversation.

Hearing Ozawa conduct the Boston Symphony in a performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 on February 13, 1986, in Tokyo was a sublime experience—a performance I consider the rarest “gift” I have ever received. Ozawa’s music is passionate, and I know that many others have been similarly impressed by him over the years. Ozawa, who turns 83 in 2018, has not been in the best of health recently. He has scaled back his activities to accommodate his physical condition, but I know I am not the only one who hopes that he will continue bringing his audiences around the world the gift of his music.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 12. Banner photo: Ozawa Seiji performs with the Berlin Philharmonic in Berlin, April 2016. © Holger Kettner; courtesy of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Jiji.)