The Social Custom of Gift Giving

Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Whether presented on a birthday or for a seasonal celebration, gifts express feelings beyond words. The Japanese tradition of zōtō (gift giving) encompasses a wide variety of occasions and has its own distinctive culture. The custom helps to keep social relations smooth and includes formal social expressions of appreciation as well as more personal gestures.

Seasonal Expressions of Thanks

Many in Japan, from families to businesses, offer seasonal gifts known as chūgen around the midsummer Buddhist Obon Festival and seibo at year’s end to show appreciation to those they frequently rely on.

Chūgen began as a custom observed as part of Obon, a summer festival for honoring ancestors. Traditionally, offerings to the souls of deceased family members were distributed among relatives and neighbors. In the 1600s the custom gradually moved away from its focus on ancestors, with merchants using the season to offer gifts to customers in appreciation for their patronage. Although still coinciding with Obon, chūgen gifts are now presented to social superiors, such as business clients or teachers.

Seibo gifts are said to have arisen from the custom of presenting offerings to the main branch of a family as part of New Year preparations. Over the centuries it has evolved into a way to express gratitude to important people in life and business, recognizing favors received during the year.

Although there is some regional variation, in general the chūgen season is from early July to mid-August, while seibo is from mid- to late December. Supermarkets and department stores will typically advertise gift sets and set up dedicated sales corners during these periods. Those proffering gifts traditionally did so in person, but these days it is socially acceptable to rely on delivery services. A recent trend has seen people turn to the Internet to purchase hard to find luxury items and rely on local stores for more common offerings. On average, households send two to three gifts per season.

Food Items Most Popular

Common offerings include gift sets of beer (the most popular item), coffee, tea, and other drinks, as well as fruit, confections, fresh seafood, and gift coupons. Within the last few years health food products have also gained popularity. Edibles are frequently chosen for the practical reason that they can be easily used up, instead of taking up space in the recipient’s home or office. Expenditures on gifts vary by who they are intended for, but in general households spend from ¥3,000 to ¥5,000 per item.

Common offerings include gift sets of beer (the most popular item), coffee, tea, and other drinks, as well as fruit, confections, fresh seafood, and gift coupons. Within the last few years health food products have also gained popularity. Edibles are frequently chosen for the practical reason that they can be easily used up, instead of taking up space in the recipient’s home or office. Expenditures on gifts vary by who they are intended for, but in general households spend from ¥3,000 to ¥5,000 per item.

One gift peculiar to Japan that has received broad attention is the gourmet musk melon. The melons sold by 180-year-old gourmet fruit vendor Sembikiya are specially cultivated, with only one fruit being produced per plant. Once reserved for the imperial household, they have now become popular upmarket gift items. Despite the exorbitant price of ¥10,000 to ¥20,000 per fruit, the melons remain much sought-after items, accounting for fully 20% of the company’s yearly sales.

Souvenirs and Reciprocation

Other important gift-giving occasions in Japan include New Year, Valentine’s Day, and Christmas, as well as events such as the birth of a child, school entrance and graduation, coming of age, marriage, building a new home, and moving house. There are also gifts for less auspicious times, including mimai for those who are sick or hospitalized and monetary kōden presented at funerals.

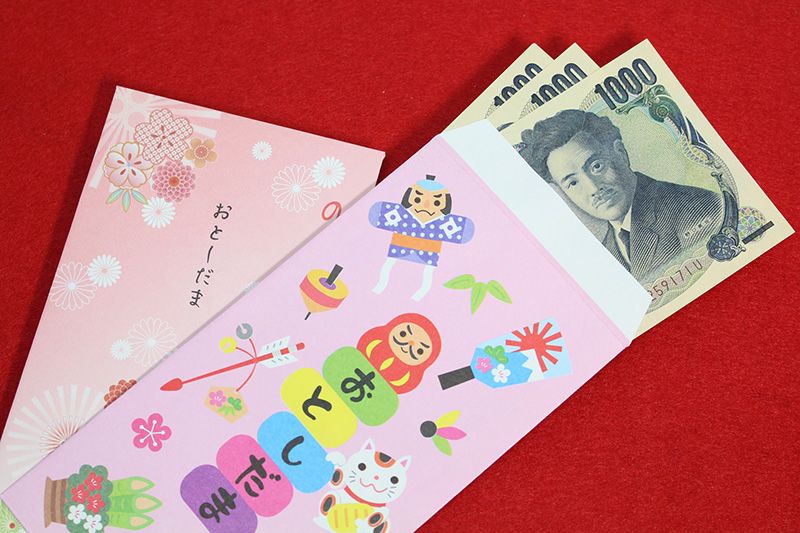

Envelopes containing otoshidama for children are often decorated with amusing images.

Envelopes containing otoshidama for children are often decorated with amusing images.

As in most other countries, travel normally entails setting aside time to buy omiyage (souvenirs) such as cookies, chocolate, or other sweets for family members and coworkers. But Japan is peculiar in the extent of this custom, with gifts commonly bought on even the shortest of trips.

A distinctive aspect of zōtō is the obligation of reciprocating with a smaller memento, known as okaeshi, to show appreciation for others’ thoughtfulness. The type of gift and variety of okaeshi varies according to the occasion, whether to thank attendees at a wedding or funeral, or to mark recuperation from illness or the birth of a baby. There is no set time period for offering okaeshi, but common custom is not let too much time lapse. The one exception is White Day on March 14, which requires boyfriends and husbands to show appreciation for the Valentine’s Day presents they received a month earlier.

Gift-Giving Etiquette

Seasonal and other gifts are traditionally wrapped in decoratively folded paper and tied with mizuhiki, a type of decorative string. Differing numbers and colors of string, as well as types of knots, are used depending on the type of gift. Nontraditional wrapping styles featuring carefully folded paper and colorful ribbons are also popular, especially for Christmas and birthday presents. Gifts of money, such as New Year otoshidama for children, are placed in special decorative envelopes called pochibukuro.

A traditionally wrapped gift tied with mizuhiki. A small piece of paper called noshi in the upper right corner signifies that the gift is for an auspicious occasion.

A traditionally wrapped gift tied with mizuhiki. A small piece of paper called noshi in the upper right corner signifies that the gift is for an auspicious occasion.

(Banner photo: A gourmet musk melon. Photo provided by Nihonbashi Sembikiya.)