"Nihonshu" Now : Yamagata and the Sake Renaissance

Guideto Japan

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

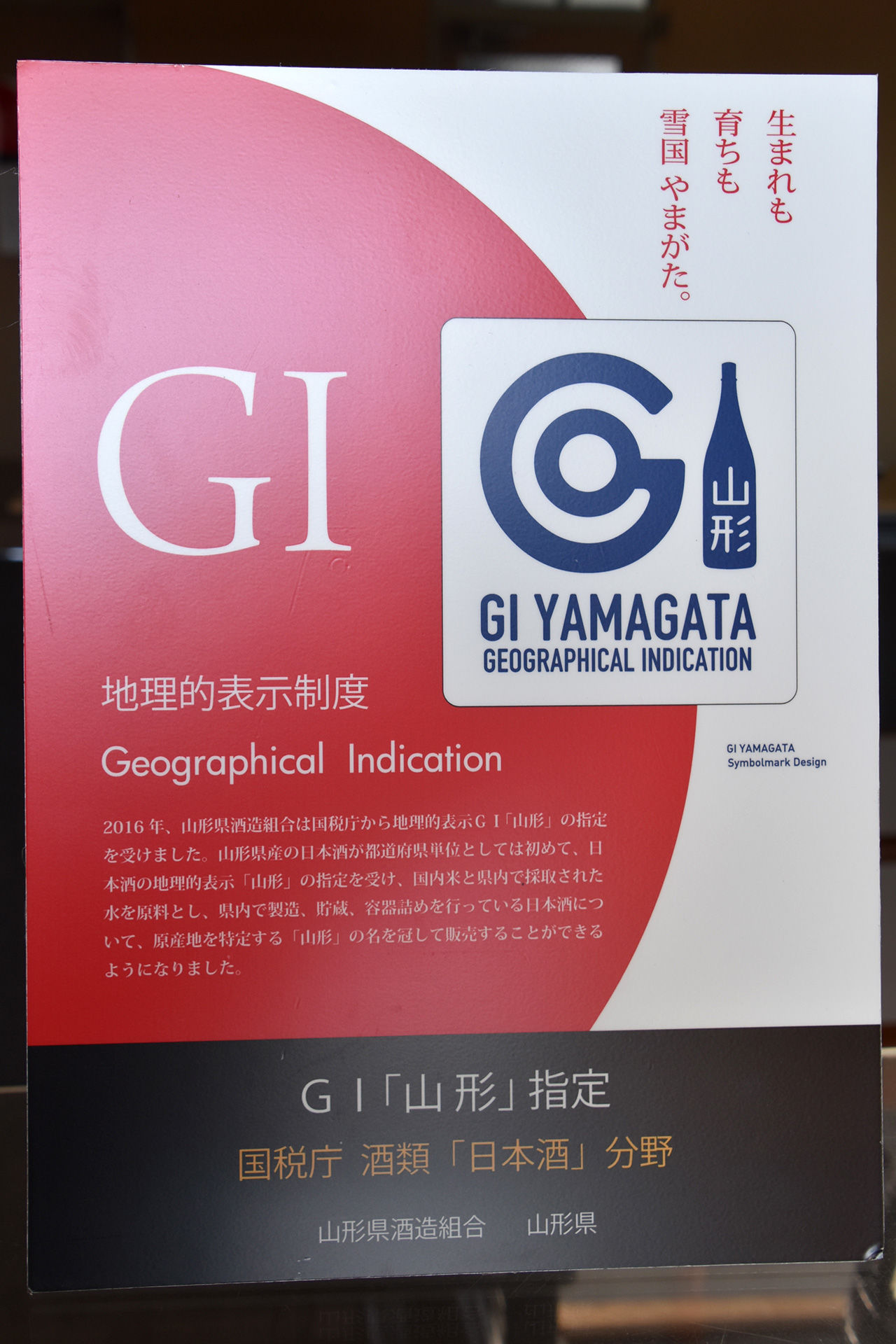

Yamagata Prefecture, a remote, snowy province on the Japan Sea coast, has emerged as one of Japan’s premier sake-producing regions, its sake beloved for its clean, light flavor profile, and its producers admired for their commitment to quality, cost performance, and innovation. Dewazakura, Jūyondai, Kudoki Jōzu, Jōkigen, and Yamagata Masamune are just a few of the brands that have earned Yamagata sake nationwide popularity, prestige, and—since 2016—its own registered geographical indication (GI).

How has Yamagata achieved this status? Through diligence, teamwork, and innovation—almost all of it concentrated in the past three decades.

The Industry at a Crossroads

The truth is that few people outside the immediate region had even heard of Yamagata sake 30 years ago. The prefecture had 53 local brewers, but they were small operations, producing mostly inexpensive, everyday sake for local distribution. Even among connoisseurs, Yamagata was not an area associated with fine nihonshu, and its products were seldom stocked by urban retailers.

For years, even small, obscure family breweries had been able to get by on local sales alone. But from the mid-1970s on, the business environment took a turn for the worse. People born in the postwar era were exhibiting a growing preference for other alcoholic beverages, including whisky, wine, and shōchū (a clear distilled liquor). Inexpensive futsū-shu (non-premium sake brewed with distilled alcohol) was hit especially hard. In a shrinking market, the big commercial sake makers had a decisive competitive edge. Many local brewers succumbed over the next decade or two.

Some, however, survived by shifting their focus to high-value-added premium sake, targeting sophisticated consumers in the nation’s urban markets. This often-painful transition took place, with varying levels of success, in regions all over Japan. What sets Yamagata Prefecture apart is the way the public and private sectors came together in a concerted effort to rescue the sake industry and revitalize the local economy.

Sake-making season in the city of Tendō. Yamagata’s cold, snowy winters can be brutal, but the low temperatures are conducive to the slow, carefully controlled fermentation that produces delicate-tasting sake with a smooth finish.

Sake-making season in the city of Tendō. Yamagata’s cold, snowy winters can be brutal, but the low temperatures are conducive to the slow, carefully controlled fermentation that produces delicate-tasting sake with a smooth finish.

Birth of “Team Yamagata”

The campaign began in 1987, when the Yamagata Sake Brewers Association established the Yamagata Brewing Research Society, a cooperative, cross-sectoral association dedicated to advancing and improving sake-brewing technology, under the guidance of the prefectural Yamagata Research Institute of Technology. This was the launch of “Team Yamagata,” a private-public partnership aimed at revitalizing the local sake industry by improving technology and nurturing human resources.

Introducing Yamagata’s impressive lineup of premium sakes is Koseki Toshihiko, a veteran sake technologist who played a key role in the private-public partnership that revitalized the Yamagata sake industry.

Introducing Yamagata’s impressive lineup of premium sakes is Koseki Toshihiko, a veteran sake technologist who played a key role in the private-public partnership that revitalized the Yamagata sake industry.

Koseki Toshihiko, a senior sake technologist for the prefecture at the Yamagata Research Institute of Technology (now retired), played a key role in building this partnership. As head of the institute’s sake research section, he drew up rules for taste testing at the workshops held almost monthly by the Yamagata Brewing Research Society. Participants were required to comment on each sample they tasted, in the presence of the maker, and to focus on the sake’s shortcomings, avoiding empty praise. “The purpose was to encourage the brewers to be open and honest with one another, sharing their techniques and their feelings,” Koseki explains. In addition to monthly meetings, a two-day annual workshop has helped to strengthen those bonds.

Another longtime Yamagata sake activist is Nakano Masami, president of Dewazakura Sake Brewery, who has participated in the society since its inception.

Nakano Masami, owner of Dewazakura Sake Brewery. The pioneering business was named Sake Brewer of the Decade at the 2016 International Wine Challenge.

Nakano Masami, owner of Dewazakura Sake Brewery. The pioneering business was named Sake Brewer of the Decade at the 2016 International Wine Challenge.

Dewazakura, established in 1892, was among the first Yamagata breweries to make the shift from quantity to quality brewing. The Tendō brewery had its first breakthrough back in 1980 (before Nakano inherited the business), with the launch of the ginjō-shu Dewazakura Ōka. Unlike the super-premium daiginjō sakes that have made such a splash in recent years, Ōka was developed with the idea of making ginjō-shu accessible to the average consumer. It was a smash hit.

“One core precept passed down through the generations [at Dewazakura],” Nakano says, “is that the owner should be present on-site, directly involved in sake brewing,” notes President Nakano Masami, Dewazakura’s fourth-generation owner. As it turned out, the company’s tradition meshed perfectly with one of the key changes spearheaded by the Yamagata Brewing Research Society: transfer of responsibility for the brewing process from itinerant professional brewmasters known as tōji to the brewery owner and employees.

“Yamagata didn’t have its own local tōji guilds,” explains Nakano, “and even in neighboring prefectures, qualified tōji were growing scarce. Instead of relying on these seasonal hires, who could always take their services elsewhere, the society’s leaders had the idea that the owners and employees of each brewery should learn the craft themselves. It was a groundbreaking concept, something no other prefecture had attempted previously.”

Supporting Open Sake Technology

The members of the Yamagata Brewing Research Society broke into teams, each devoted to one aspect of the sake-making process—rice, yeast, kōji, and so forth. At workshops held 10 times a year, members reported on team findings and listened to presentations delivered by tōji from other prefectures, logistics experts, and other guest lecturers. Then they would taste and comment on samples from participating breweries. The meetings have been going on for 30 years now. In addition, members gather once a year for a two-day workshop at a secluded inn. Daytime is devoted to training sessions and presentations. In the evening, brewers young and old assemble to taste local sake and exchange frank opinions, often with considerable ardor.

“The atmosphere in Yamagata today is one in which you can say what you think, even to your elders,” says Gotō Takanobu of Gotō Kōtarō Shuzōten (Takahata). “At the same time, with everyone brewing sake at such a high level, you’re really inspired to up your game.”

Three generations of Yamagata sake men: from left to right, Nakano Masami of Dewazakura Brewing Company, senior sake technologist Koseki Toshihiko, and Gotō Takanobu of Gotō Kōtarō Shuzōten.

Three generations of Yamagata sake men: from left to right, Nakano Masami of Dewazakura Brewing Company, senior sake technologist Koseki Toshihiko, and Gotō Takanobu of Gotō Kōtarō Shuzōten.

The Yamagata Research Institute of Technology played a crucial role in supporting the development of brewing technology by pooling technical information from the prefecture’s breweries and creating a network to make it available to all members. It gathered data on everything from rice moisture content to mash temperatures, analyzed the figures, and fed the results back to the breweries to provide open access to the most advanced brewing techniques. Experts from the institute toured Yamagata breweries individually during the sake-making season—often staying overnight—to offer technical guidance.

“What we really wanted to get across to the brewers,” says Koseki, “was our love of science and sake.” The owners responded to that passion with heroic efforts of their own.

Sake technologist Ishigaki Hiroyoshi holds a sample of an original Yamagata yeast strain. The Yamagata Research Institute of Technology where he works has its own rice-milling and brewing equipment, as well as special temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms for culturing the kōji mold so critical to sake making. Ishigaki sometimes stays overnight to conduct brewing experiments.

Sake technologist Ishigaki Hiroyoshi holds a sample of an original Yamagata yeast strain. The Yamagata Research Institute of Technology where he works has its own rice-milling and brewing equipment, as well as special temperature- and humidity-controlled rooms for culturing the kōji mold so critical to sake making. Ishigaki sometimes stays overnight to conduct brewing experiments.

Open technology was essential to the rebirth of Yamagata’s sake industry. For hundreds of years, the tōji had guarded the secrets of brewing fine sake. Becoming a brewmaster required long years of arduous apprenticeship, during which one was obliged to “steal” the secrets of the master bit by bit while working as a low-paid assistant. Only those rare individuals possessed of unusual talent, grit, and perseverance could hope to reach the pinnacle of the profession. In Yamagata, a team of brewery owners and technocrats broke this monopoly, leveraging communal knowledge and sheer enthusiasm to nurture a generation of artisanal brewer-owners.

Over a period of three decades, their efforts transformed Yamagata into one of the nation’s premier sake-producing regions. At the 2004 Japan Sake Awards, held by the National Research Institute of Brewing, Yamagata won more gold medals than any other prefecture, and it has maintained the number one spot ever since. A full 78% of all the sake produced in Yamagata is premium grade, as compared with the nationwide average of 34% (according to 2017 figures from the National Tax Agency). Moreover, all of its brewing operations are directly managed by the owners or their permanent employees. The prefecture’s breweries excel at everything from value for money to new product development (sparkling sake, for example).

The Road to “GI(*1) Yamagata”

Having secured the prefecture’s reputation as a sake-brewing region, Team Yamagata’s next objective was to enhance and guard that reputation by means of a protected geographical indication. The campaign began in earnest in 2011.

By international agreement, GIs are limited to products that possess qualities or a reputation linked to their geographical origin. Yamagata certainly qualifies in this respect. It has developed its own proprietary strains of sake rice, yeast, and kōji. Flavor-wise, Yamagata sake is distinguished by its clean, “transparent” taste and smooth finish. The main hurdle to official GI registration was the establishment of a formal evaluation and certification system to guarantee product quality.

The members of the Yamagata Sake Brewers Association were not opposed to such a system in principle. They had been submitting their sake to the Yamagata Brewing Research Society for evaluation ever since 1987. Gradually, the industry’s leaders hammered out a plan for the creation of a tasting panel consisting of eight to ten members, including academics, inspectors from the National Tax Agency (which has jurisdiction over the liquor industry), and other outside experts. The panel would conduct reviews ten times a year for each category of sake (junmai, ginjō, daiginjō, and so forth).

The biggest challenge was drawing up evaluation criteria that all of the association’s 50-odd breweries could agree on. Still, with its history of collaboration and commitment to product quality, Yamagata had a significant head start over other prefectures. Agreement was reached, and in December 2016, after five years of planning and lobbying, Yamagata sake was granted a registered geographical indication. The first bottles bearing the distinctive “GI Yamagata” label hit the market in January 2018.

(*1)^Geographical indication (GI)

A geographical indication (GI) is a kind of trademark protecting the regional appellation of a product whose quality, reputation, and other established characteristics are attributable to its geographical origin. Champagne, Roquefort, and Darjeeling are well-known examples. A registered GI mark, granted by the national government to products meeting specific criteria, certifies a product’s origins and conformance with quality standards. Yamagata specialties registered under Japan’s GI system (established in 2015) include Yonezawa beef and Higashine cherries, as well as Yamagata sake. Other GIs in the sake category are “Japanese sake/nihonshu” and Hakusan Kikusake from the city of Hakusan in Ishikawa Prefecture.

Yamagata Goes Global

Thanks to the tireless efforts of brewers around the nation, premium nihonshu is enjoying an unprecedented boom in sales, not only in Japan but overseas as well. The total value of Japan’s sake exports in 2017 was about ¥18.7 billion, a new record. Yamagata has been a pioneer in this area as well. Dewazakura began exporting its premium sake some 20 years ago and now ships its products to 30 countries around the globe. Altogether, Yamagata exports more sake than any other prefecture in the Tōhoku area. The new geographical indication is sure to boost overseas sales further, as consumers learn to associate the “GI Yamagata” designation with a smooth, clean flavor profile—much as diners partial to light-bodied whites quickly pick out a Chablis from the wine list.

The flagship products of Dewazakura Sake Brewing Co: Dewazakura Ōka, the hit ginjō-shu launched in 1980; Dewanosato junmai-shu, the 2013 IWC Champion Sake; and Ichiro junmai daiginjō-shu, the 2008 IWC Champion Sake.

The flagship products of Dewazakura Sake Brewing Co: Dewazakura Ōka, the hit ginjō-shu launched in 1980; Dewanosato junmai-shu, the 2013 IWC Champion Sake; and Ichiro junmai daiginjō-shu, the 2008 IWC Champion Sake.

Some boosters insist that the best way to enjoy Yamagata sake is to go straight to the source. “You really have to visit,” urges Nakano. “Relax in one of our hot springs, enjoy a run down one of our excellent ski slopes, dine on our Yonezawa beef or Higashine cherries, and savor the pure, clean flavors of our Yamagata sake.”

My advice is to try Yamagata sake the first chance you get. And when you do, try to envision the human faces behind Japan’s sake renaissance: the dedicated, tireless team of brewers and technicians who pushed one another to new heights, inspired by their love of sake and their devotion to Yamagata Prefecture.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The “GI Yamagata” mark certifies the sake thus labeled as originating in Yamagata Prefecture and conforming to rigorous quality standards. Courtesy of Yamagata Sakanaichi. Other photographs by Sandō Atsuko. Series banner image by calligrapher Kanazawa Shōko)