Pursuing the Possibilities of “Hariko”: Artisan Hashimoto Shōichi Branches Out in New Directions

Guideto Japan

Art Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Hashimoto Shōichi is the twenty-first head of Honke Daikokuya, one of the establishments in the Takashiba Deko Yashiki group of craft-making companies in the hills on the outskirts of Kōriyama, Fukushima Prefecture. Here he works with washi paper to create hariko, traditional papier-mâché dolls and other figures. Washi, he enthuses, “is very pliable, so it allows me to create hariko of any shape or size. To me, that opens the door to infinite possibilities for creative expression.”

Hashimoto Shōichi holding a Miharu-hariko daruma doll.

Four workshops in the Takashiba district of Kōriyama have been in operation for over three hundred years. This was once part of the domain of the former Miharu clan of Fukushima Prefecture, providing the names for their wares: the Miharu-hariko figures and Miharuoma horses The first dolls in Japanese history were clay dogu and, later on, figures fashioned from wood called deku or mokugū. The pronunciation of deku morphed into deko. Today’s Takashiba Deko Yashiki, the “Takashiba doll houses,” which sell hariko crafts, are a tourist attraction in their own right.

“In the Edo period, hariko became popular as toys and lucky charms,” explains Hashimoto. “Peddlers sold hariko dolls all over the Tōhoku region and even as far south as Edo, or present-day Tokyo.”

The Deko Yashiki Daikokuya Product Hall is the gateway to the Takashiba Deko Yashiki complex. The Oichi-chaya structure to the right is a combined rest stop and lunchroom.

Exterior view of the Honke Daikokuya workshop. The gray-roofed building to the left is a restored traditional farmhouse where Hashimoto exhibits his works.

Curves and Straight Lines

Hariko figures are made by patting wetted washi onto wooden forms, after which glue is applied and the forms are left to dry. Once the paper is dry, the wooden form is extracted through a cut in the figure. The cut is then pasted over with nikawa, an adhesive made by boiling fish or animal skins and bones, which is also used to attach decorations. The whole is then given a base coat of gofun, a whitewash made from roasted, crushed seashells, before the final touch—the addition of a hand-painted design. To reinforce the items, multiple layers of washi are used. The wooden forms used for creating dolls, roly-poly daruma figures, and masks have been handed down over generations at each Deko Yashiki workshop.

Wooden forms for a hyottoko mask, a humorous depiction of a man sometimes used in dances at local festivals. The forms, blackened with age, are brushed with oil to make the dried washi easier to remove.

Torn pieces of wet washi are pressed firmly onto a wooden form.

The forms are given a wash of gofun, a white powder made from roasted, crushed seashells. Eto figures for the Year of the Rat are shown here, drying on a bamboo basket representing a rice bale.

The multiple layers of washi used for hariko-making afford a high degree of flexibility and allow the creation of elegant forms. The most common hariko figures are the 12 eto creatures of the Chinese astrological calendar, lucky charms, or votive offerings.

Hariko talismans are also popular. One of the best-known is the tora (tiger), representing parents’ hopes that their children grow strong and resilient. In wartime, tora figures were often displayed outside the homes of families with sons sent to war as a wish for their safe return, just as the tiger always returns to its den after going far away to hunt.

The Takashiba Deko Yashiko is also a renowned producer of Miharu-goma, wooden figures that come in either black or white. The black koma represents the wish to be blessed with children or is a prayer for children’s health, while the white one is a wish for longevity and security in old age.

Flexible washi lends itself to creating the dynamic, raised-rear pose of the koshidaka tora.

The crisp, angular lines of Miharu-goma horses contrast with the rounded forms of hariko. A Miharu-goma was featured on the New Year stamp for the 1954 Year of the Horse.

The work of hariko-making consists of three steps: pasting washi onto wooden forms, painting designs, and selling the finished product. Hashimoto acts as his own salesperson and needs to wait on customers, so his workspace occupies one corner of the sales floor. The Takashiba area has long been a popular tourist spot and tends to attract many visitors on weekends and over the yearend and New Year holiday, which keeps Hashimoto busy in the shop selling the eto and daruma good-luck charms that he makes.

Hashimoto recalls that until his parents’ generation, hariko-making was a side business for farmers. “My parents were really hard workers, always busy out in the fields or making hariko. But since they were so occupied all the time, as a child I felt starved for attention and I had no desire to follow in their footsteps.” Hashimoto attended a fine arts university and became a high school art teacher. He enjoyed teaching, but had to leave the job after six years to take over the family trade when his father fell ill. After an apprenticeship period, he became head of Honke Daikokuya in 2010.

Hashimoto’s creations are on display at the Honke Daikokuya atelier, among a colorful array of hariko figures.

Hashimoto in a corner of his shop, painting a design onto a Miharu-goma figure.

Spurred On by the March 11 Disaster

Hashimoto works in the traditional style, but he has long believed that the possibilities for hariko are infinite. The March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami disaster provided a major impetus for him to branch out in new directions.

Situated about 50 kilometers inland from the coast, Takashiba was not harmed by the tsunami; the district is also on solid ground, and the earthquake caused elatively little shaking or damage there. But the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, which suffered reactor core meltdowns in the disaster, is also around 50 kilometers away, and in the days immediately after the earthquake, Hashimoto worried that he might have to evacuate.

Even though life in Takashiba continued relatively normally, with electricity and running water available as usual, the disaster was hugely upsetting. Hashimoto stopped working for a time but eventually started up again, motivated by the desire to help the affected Tōhoku region get back on its feet. Inspired by the daruma doll, which represents picking oneself up after the ups and downs of life, he decided to adopt the daruma as the symbol of the region’s reconstruction and revival efforts.

After locating a suitable wooden form in his storehouse, Hashimoto got to work creating a “Pray for Reconstruction” daruma. Compared to the typical round daruma shape, Miharu-daruma are elongated and feature a red face and eyes flashing in a piercing stare, which, according to popular belief, has the power to ward off disaster.

Hashimoto took the daruma, with the characters 復興 (fukkō, or reconstruction) on its belly, to fund-raisers and events all over Japan to sell Tōhoku products. He invited people to write messages of encouragement onto the body of the daruma, an idea that received considerable media attention.

The “Pray for Reconstruction” daruma, covered in messages praying for the revival of the devastated Tōhoku region.

Creative Encounters

Hashimoto’s activities for supporting Tōhoku brought him into contact with people outside the traditional craft world. One of these was former Japan national soccer team player Nakata Hidetoshi, who spearheaded the Revalue Nippon Project to promote and encourage the development of traditional crafts.

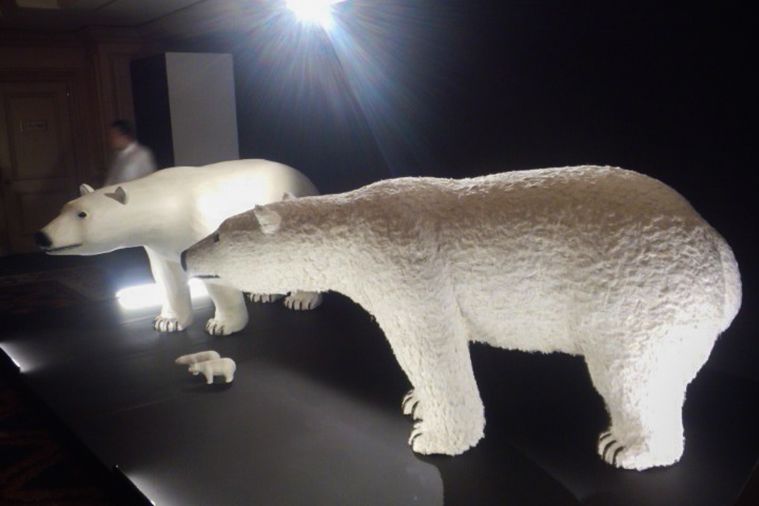

In June 2011, Hashimoto joined a team led by Nigo, founder of the A Bathing Ape apparel brand, and worked with renowned interior designer Katayama Masamichi to create a 2.4-meter-long hariko polar bear. The scale of this gigantic figure was unlike anything that Hashimoto had ever attempted before, but he said that the hardest part of the job was creating realistic-looking fur. He succeeded by feathering the washi fibers to make them look like fur. His creation became the most-featured item in the project.

The polar bear hariko exhibited at the Take Action Charity Gala 2011. The washi is feathered to create realistic-looking fur. (Courtesy Hashimoto Shōichi)

East Japan Project led by Kuma Kengo, the architect who designed Tokyo’s new National Stadium. Hashimoto was put in charge of designing a pen channeling two Fukushima folk toys, the pointy-headed okiagari koboshi, which rises once more when toppled over, and the red akabeko cow.

Hariko-making skills are being passed on in many parts of Japan. The problem, though, is the dearth of artisans who can make the wooden forms for the hariko. Hashimoto, who grew up watching his parents making hariko and who studied fine arts, has been the ideal person to participate in Tōhoku support projects and take his traditional craft one step further.

Hashimoto created these folk-design inspired pens, which stand upright when tipped over, in 2013. They feature designs by Harada Masahiro, principal of Mount Fuji Architects Studio.

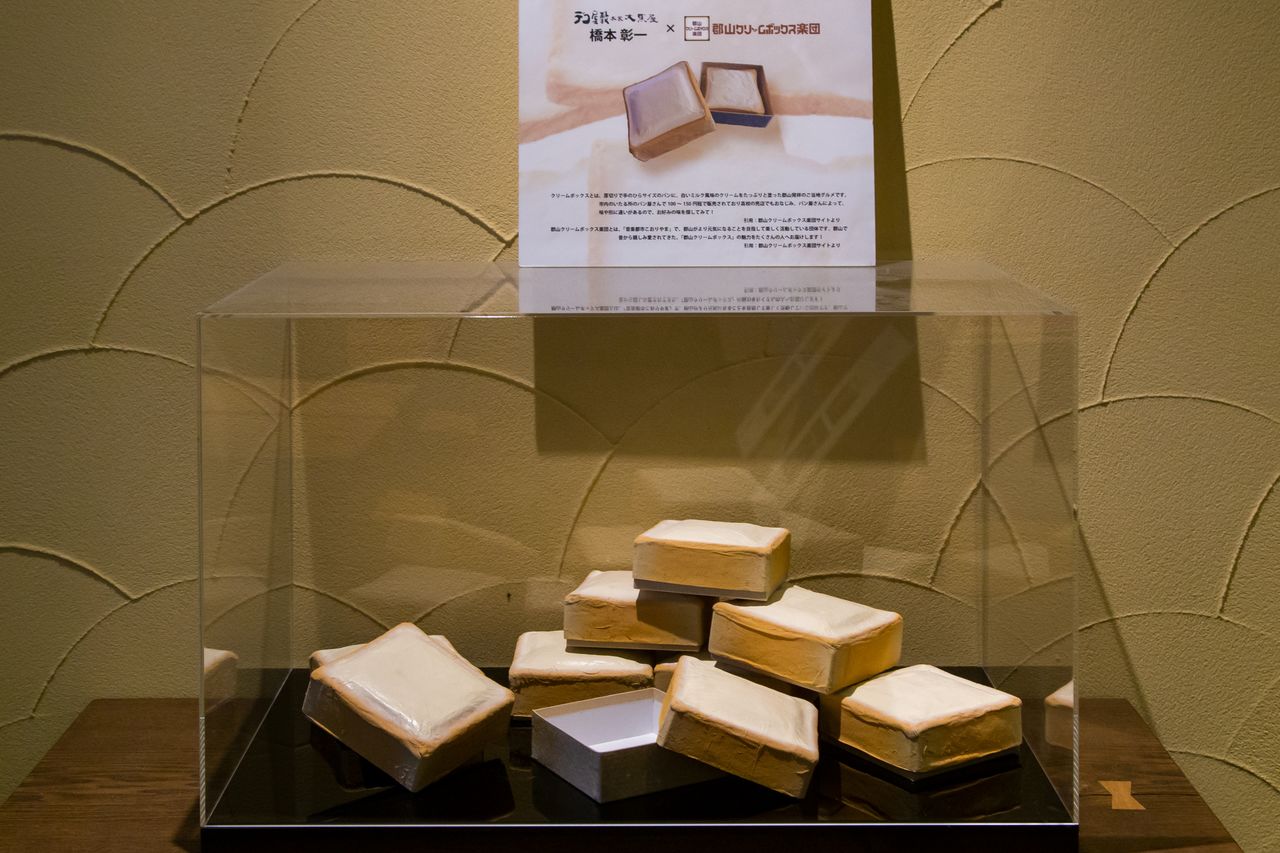

The koshidaka tora and the daruma Hashimoto created in 2016 in collaboration with fashion designer Koshino Junko are still sold at Honke Daikokuya. Hashimoto also supports local businesses, having created hariko packaging for Cream Box sandwiches that looks exactly like the treats inside, and has branched out into wearables like Deko Megane hariko eyewear and washi jewelry marketed under the Harico brand.

Adversity and opportunity are two sides of the same coin. After the turmoil of the March 11 disaster, Hashimoto went into action; his spirit of initiative led to many new connections and directions. Thanks to these opportunities, he acknowledges, he is able to preserve tradition while creating something new.

Tiger figures by Koshino Junko sport distinctive zebra stripes.

This hariko packaging mimics the original Cream Box, a popular local bread-based treat with a creamy filling.

Supporting the Fukushima Brand

Since the March 11 disaster, the number of visitors to Takashiba Deko Yashiki has fallen by more than half. Nine years later, numbers still have not rebounded. As a former teacher who enjoyed interacting with students during hands-on hariko painting sessions, Hashimoto is disappointed is that no organized school tours have been visiting Deko Yashiki at all over the past few years.

The Honke Daikokuya building is used for hands-on painting sessions by large groups. But fewer school groups come through nowadays, so the building is not used as often as before.

“Because of the disaster, Fukushima’s farmers and fishers still labor under the stigma that their produce and catches are tainted. Although it may be unseemly to say so, I think it’s up to artisans like me to raise Fukushima’s profile and give it a more positive image. Even before the March 11 disaster, Fukushima didn’t have much presence within Japan, but now it’s known throughout the world and people everywhere are concerned about our welfare.”

Hashimoto makes a point of traveling abroad, exhibiting his works at promotional events for Japan. He searches out local artisans around the world to compare notes with them and says he is genuinely surprised that so many people know Fukushima now. He works hard to create a positive image for his home, given that previous time and money spent on profile-raising activities by the prefecture and local tourism associations have produced little success.

Hashimoto dreams of holding a traditional Spanish celebration, the Fallas of Valencia, in Fukushima someday. That festival consists of parading papier-mâché figures more than 10 meters tall through the city’s streets over five days, with people singing, dancing, and drinking all the while. In the event’s finale, a single figure is chosen as the grand prize winner and all the others are torched in a gigantic bonfire. Obtaining information from Spanish artisans, Hashimoto is working hard to bring the festival to Fukushima.

Hashimoto at the Fallas festival, wearing a Miharu-hariko hat. (Courtesy of Hashimoto Shōichi)

Hashimoto further describes his dream in these words. “Fukushima is the home of some of Japan’s best-known hariko creations, like the Aizu akabeko and the Shirakawa daruma. I’d love to organize a festival where local artisans create huge papier-mâché figures and parade them around the prefecture, an event that would culminate on the final day with a bonfire like Japan’s New Year dondo yaki bonfires. A festival like that would really put Fukushima on the map. It would also help draw attention to the traditional craft of hariko and encourage artisans to boost their skills.”

Takashiba Deko Yashiki Honke Daikokuya

- Address: 163 Tateno, Takashiba, Nishita-machi, Kōriyama, Fukushima Prefecture

- Open year-round

- Hours: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm

- Tel.: 024-981-1636

(Translated from Japanese. Reporting, text, and photos by Nippon.com except where otherwise noted.)