Glimpses of a Glittering North: Mizukoshi Takeshi’s Hokkaidō Photography

Frozen Landscapes Forged by Volcanic Fire

Guide to Japan Environment Travel- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Hokkaidō’s mountains are, on average, about 1,000 meters lower than those of the Japan Alps. As such, they require no advanced climbing techniques. Even Asahidake, the tallest mountain in Japan’s northernmost prefecture, is a mere 2,291 meters high. But in the depths of winter, daylight hours are short and temperatures can plunge to nearly –40º Celsius. There is also the challenge of large low-pressure systems, which can bring snowstorms lasting for a week or more. Given Hokkaidō’s high latitude, seasonal winds also drive massive accumulations of snow, bringing to mind mountains in much more rigorous terrain. All these conditions necessitate the mental fortitude to withstand blizzards that might occur at any time. Approaching Hokkaidō’s mountains in winter is by no means easy; climbers are well advised to plan a careful schedule and carry sufficient food and fuel for their projected journey.

At the age of 84, Mizukoshi Takeshi took this photo of 1,721-meter Mount Rishiri in the depths of winter. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Except in July and August, traversing the length and breadth of Hokkaidō’s mountains is a daunting undertaking. For this reason, until comparatively recently, ordinary climbers tended to overlook the interior’s mountainous regions, and there have been few opportunities to introduce this territory in depth.

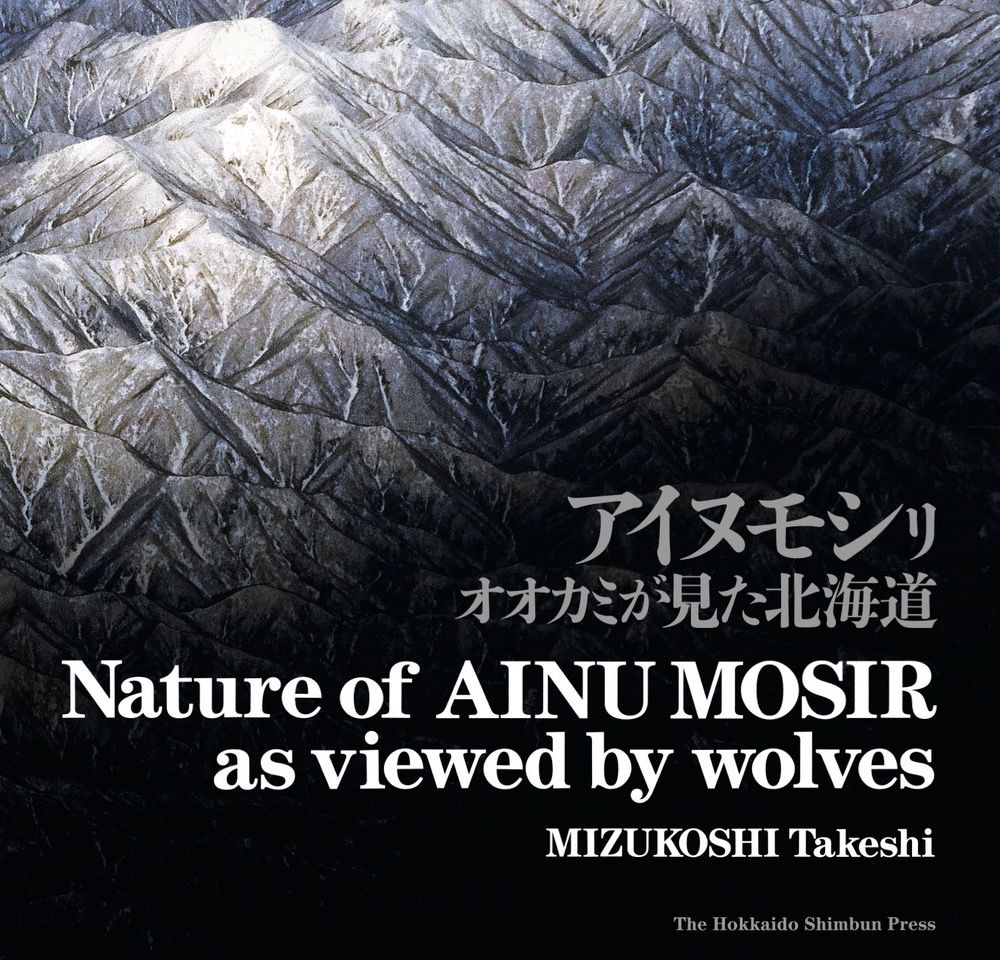

Mountain ranges in Hokkaidō’s interior. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Asahidake, Highest Peak in the Daisetsuzan Range

Daisetsuzan refers to the Daisetsuzan group of volcanic peaks in the center of Hokkaidō. Asahidake, the range’s main peak, is Hokkaidō’s tallest mountain. As part of a cluster of composite volcanoes, Asahidake seems to me more like a mountain standing in an expansive lava field than a tall peak standing alone.

Asahidake, the main peak of the Daisetsuzan range, during heaviest snow accumulation. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

The first time I climbed in the Daisetsuzan range was in July 1971, together with my mentor, the renowned photographer Tabuchi Yukio (1905–89). From our rock chamber base on the 2,230-meter Hakuundake, we conducted an ecological survey of alpine butterflies, but although we spent over a week on the mountain, I did not get to Asahidake that time.

Water springs from numerous small calderas in the Daisetsuzan range, forming streams that flow through the mountainous terrain. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Frankly, entranced by the wide-open skies and the gently rolling landscape, I lost the desire to stand atop the highest peak. Even though Asahidake was a mere two or three hours’ walk away, as a man who lived to climb mountains I am embarrassed to admit to such a feeling. It may be that the open terrain of the Daisetsuzan range seemed more like highlands to me. And rising in those highlands, it was actually Mount Tomuraushi, just slightly lower than Asahidake at 2,141 meters, that stimulated my desire to climb; I went there and back from our rock chamber base on Hakuundake. In fact, it was only 20 years later than I summitted Asahidake, in March, when the snow was at its deepest.

Looking toward Mount Tomuraushi, in the southern part of the Daisetsuzan range, with ezo-kanzō flowers blooming in the marshes of Numanohara and Ōnuma. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Winter in the Daisetsuzan range. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Rolling terrain creased and crevassed by repeated freeze-thaw cycles of moisture in the ground is everywhere in the Daisetsuzan range, creating a rich environment for plant and animal life particular to the area. Permafrost remains here and there, as well as Ice Age relict species of high-altitude insects and plants, including such butterfly species as the usubakichō (Eversmann’s parnassian) and the daisetsu takane hikage (Melissa Arctic), which are found only in the Daisetsuzan range.

A view of the 1,967-meter Ishikaridake, the main peak in the eastern part of the Daisetsuzan range, photographed from the Numanohara marsh. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Autumn foliage at the treeline at Daisetsuzan. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

The Hidaka Mountains, an Ice Age Relic

There is no better way to experience glaciated terrain than to explore the steep Hidaka Mountains. Many of the mountains are volcanic, and, unusually for these parts, the terrain is creased and folded due to crustal movements. Poroshiridake, the highest peak, stands 2,052 meters tall, and the range’s beautiful mountains stretch 80 kilometers north to south, from Karikachi Pass to Cape Erimo. This is a mature mountain range, with craggy peaks and narrow knife-edge ridges. In part due to the steepness, little snow remains above the tree line into the warmer months, allowing the growth of thick stands of Siberian dwarf pine on the upper slopes. In the foothills, woods of conifers such as Sakhalin fir and Ezo spruce abound.

The central portion of the Hidaka Mountains. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Cirques, hollowed-out areas near the peaks and ridges of the mountains caused by glacial erosion, are a characteristic feature of the terrain here. These depressions were formed during the last Ice Age, which lasted from around 70,000 to 10,000 years ago. Although there is no actual mountaineering trail, the 100-kilometer trek from 1,754-meter Memurodake in the north to Rakkodake (1,471 meters) in the south is a popular route.

Beauty Born of Volcanic Activity

Out of Hokkaidō’s six national parks, all except for Kushiroshitsugen National Park, which centers on Japan’s largest marsh, incorporate volcanic mountains. Formed through repeated eruptions over eons, they include peaks like the off-limits 737-meter Mount Usu, an active volcano that rumbles and belches smoke, although most others can be climbed safely with the assistance of experienced guides.

Sulfur crystals continue to grow in the numerous smoking vents of 508-meter Mount Iō in Akan-Mashū National Park. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Hokkaidō’s largest volcanic range runs from 2,077-meter Tokachidake to the Daizetsuzan mountains and the Shiretoko Peninsula as part of the Chishima volcanic range. It forms a crescent shape from the beautiful conical 1,370-meter Oakandake, part of the Akan volcanic range, to the Shiretoko volcanic range, with 1,661-meter Rausudake being the highest peak on the Shiretoko Peninsula.

The emerald green pond at volcanically active Meakandake, with 1,476-meter Akan Fuji in the background. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Puffs of steam rise from the 1,499-meter Meakandake during periods of volcanic activity. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Winter scene: Meakandake, with Akan Fuji to its right. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

The mountains of the Shiretoko range peek through a sea of clouds. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Shiretokodake, 1,254 meters tall, in early summer. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Lake Mashū, which lies in the Chishima volcanic range, is surrounded by 300-meter-high crater walls. This caldera lake is famed for having waters among the world’s clearest, with transparency to a depth of 41.6 meters as measured in 1931. Opportunities for viewing the lake are limited, though, as it is also notable for being shrouded in fog, giving it a mysterious allure.

Lake Mashū, a crystal-clear caldera lake, shows continually changing aspects depending on the season. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

Although Hokkaidō’s summers are short and winters are long, the seasons do manifest themselves in its mountains. After lengthy, harsh winters, the long-awaited buds in the sparkling dark earth emerging from the snow in spring and the nanakamado Japanese rowan and dakekanba birch bursting with color at the tree line in autumn are all the more dazzling for their brief appearances.

The 1,254-meter Shiretokodake in early summer. (© Mizukoshi Takeshi)

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Winter on the 1,046-meter Tenchōzan. Hokkaidō’s mountains, at a high latitude, call to mind higher, more extreme environments. © Mizukoshi Takeshi.)