Ama: A Remote Island Community Shows It Can Win the Fight Against Decline

Economy Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Ama’s Remarkable Achievements

At a time when many outlying areas of Japan are beset by aging and depopulation, there is one remote hamlet that has been thriving in recent years and has caught the nation’s attention. Thanks in part to an influx of new residents, notably younger people who have no previous ties to the district (a phenomenon known in Japan as “I-turn”), the town of Ama in Shimane Prefecture—perched on the island of Nakanoshima in the Oki Islands some 60 kilometers offshore in the Sea of Japan—has found new, lucrative markets for its many local products. It is also a community where local residents are actively engaged in securing their own future well-being through their participation in the drafting of the town’s comprehensive development plan. Ama’s achievements have been so remarkable that it was singled out by Prime Minister Abe Shinzō in his September 2014 policy speech as a model for regional revitalization.

At a time when many outlying areas of Japan are beset by aging and depopulation, there is one remote hamlet that has been thriving in recent years and has caught the nation’s attention. Thanks in part to an influx of new residents, notably younger people who have no previous ties to the district (a phenomenon known in Japan as “I-turn”), the town of Ama in Shimane Prefecture—perched on the island of Nakanoshima in the Oki Islands some 60 kilometers offshore in the Sea of Japan—has found new, lucrative markets for its many local products. It is also a community where local residents are actively engaged in securing their own future well-being through their participation in the drafting of the town’s comprehensive development plan. Ama’s achievements have been so remarkable that it was singled out by Prime Minister Abe Shinzō in his September 2014 policy speech as a model for regional revitalization.

Ama, indeed, offers many hints for others to follow, which I will examine below. Of great importance in undertaking such an analysis is to recognize that the accolades Ama is winning today are not the products of isolated developments but represent the fruits of a grand project involving many interconnected factors. Also indispensable is the task of delving into the reasons behind the flourishing of such a project in this particular community. There are plenty of examples of outlying regions that have seen an influx of newcomers, a revival of economic activity, or a heightened awareness of local autonomy. How was it that all three came together in this remote island on the “backside” of Japan?

“Make Do with What’s Available”

Nakanoshima, the island on which Ama is located, is just 89 kilometers in circumference, and getting there from the mainland takes three hours by ferry. Because it is so inaccessible, the island is blessed by unspoiled natural beauty, and many political prisoners—including aristocrats—were exiled there. One of them was Retired Emperor Go-toba, who composed many waka poems during the 19 years he spent on the island after losing the Jōkyū War to the Kamakura shogunate in 1221.

Nakanoshima, the island on which Ama is located, is just 89 kilometers in circumference, and getting there from the mainland takes three hours by ferry. Because it is so inaccessible, the island is blessed by unspoiled natural beauty, and many political prisoners—including aristocrats—were exiled there. One of them was Retired Emperor Go-toba, who composed many waka poems during the 19 years he spent on the island after losing the Jōkyū War to the Kamakura shogunate in 1221.

Objectively speaking, by no means can Ama be said to be blessed with natural advantages. Its main link to the mainland is a ferry that takes three hours one-way (although a high-speed boat has recently begun servicing the island). Traveling to any of the other islands is also by boat, turning an errand on the other shore into a day-long excursion. Ferry service is often suspended when the waves are high, and one can be stranded for days during the typhoon season. Winter seas are also frequently stormy. As for flights, there is only one roundtrip service per day to Osaka and nearby Izumo.

Another serious problem for residents is the absence of obstetricians. There is a general hospital on the big island of Okinoshima with a department of obstetrics and gynecology, but there is no longer a full-time physician there—although one had been dispatched by a university hospital in the past—reflecting the nationwide shortage of maternal healthcare providers. Many pregnant women thus choose to give birth on the mainland, and they may need to be carried there by helicopter in case of an emergency.

While these conditions apply to all of the Oki Islands, the situation is particularly severe in the town of Ama. It is not the biggest of the sparsely populated Dōzen group of islands; it has no airport, no obstetrician, and not even a convenience store. One of the first things that visitors see after coming ashore in Ama are posters at the adjacent Kin’nya Monya tourist center (the name refers to a popular folk song on the island) that read Nai mono wa nai (Make Do with What’s Available). If one were to list the facilities and services that Ama does not have, there would be no end to the task.

The Kin’nya Monya tourist center, located next to the port in Ama, at dusk (left); staff members and the Nai mono wa nai posters at the center (right).

The Kin’nya Monya tourist center, located next to the port in Ama, at dusk (left); staff members and the Nai mono wa nai posters at the center (right).

While the poster defiantly proclaims that there is no point coveting what you do not have, it also draws one’s attention to the riches that are available. Surrounded by the sea with abundant marine products, Ama has many springs of clean, pure water that allow the island to be self-sufficient in rice. Rather than dwell on the negative, the poster urges residents to enjoy the abundance at hand. Interestingly, Nai mono wa nai can also be read to mean that there is nothing unavailable—that is, everything is already here, if you just use a little ingenuity. For instance, there was no library in Ama, so residents donated books and turned the entire island into one big library. The town’s slogan thus appears to embody the positive, can-do mentality of its citizens.

Ama may be a small island, but it is rich in tourism resources. Top row: The Amanbō semisubmersible leisure boat cruising around the Saburō Rocks (left); Akiya Beach, popular with campers and swimmers in the summer (right). Middle row: The summer festival at Utsuka Mikoto Shrine in honor of a local deity (left); Oki Shrine, dedicated to Emperor Go-Toba, is renowned for its cherry blossoms (right). Bottom row: The Kin’nya Monya Festival in August is one of the biggest events of the year. Mayor Yamauchi Michio throws “fortune rice cakes” into the crowd (left); dancers, young and old, step to the lively strains of “Kin’nya Monya” holding large wooden spoons.

Ama may be a small island, but it is rich in tourism resources. Top row: The Amanbō semisubmersible leisure boat cruising around the Saburō Rocks (left); Akiya Beach, popular with campers and swimmers in the summer (right). Middle row: The summer festival at Utsuka Mikoto Shrine in honor of a local deity (left); Oki Shrine, dedicated to Emperor Go-Toba, is renowned for its cherry blossoms (right). Bottom row: The Kin’nya Monya Festival in August is one of the biggest events of the year. Mayor Yamauchi Michio throws “fortune rice cakes” into the crowd (left); dancers, young and old, step to the lively strains of “Kin’nya Monya” holding large wooden spoons.

Rejecting the Easy Path

The future did not always appear bright for Ama, for like many other outlying areas in Japan, it too struggled to meet the challenges of depopulation and a falling birthrate during the many years that its economy was dependent on public works. Public debt continued to swell during those years, and by 2003 the amount allocated for the repayment of municipal bonds reached one-third of total annual expenditures. An additional blow was the “trinity reforms” of 2003, which resulted in a drastic reduction of state subsidies. Ama was just a step away from requiring national oversight to recover from its debts.

One option it had was to merge with neighboring municipalities, as many others around the country were doing to streamline administrative costs. But for Ama—separated from its closest neighbors by the sea—the likelihood of achieving greater efficiency through consolidation appeared slim. So Mayor Yamauchi Michio organized community meetings in each of Ama’s 14 districts to ask residents directly whether they wished to merge with other municipalities. Their conclusion was that Ama should seek revitalization on its own; by choosing what they knew would be a difficult path, residents braced themselves for the challenges ahead.

Town hall took the first step toward fiscal consolidation. Mayor Yamauchi cut his own pay, and other municipal officers, including the rank and file, followed suit. Slashing the budget was not enough to revitalize the community, though; of greater importance was what to do with the amount saved. The decision Ama took was to invest the unspent expenditures on a new freezing technology called the Cells Alive System that did not destroy cell tissue and thus enabled the preservation of seafood with greater freshness. The system was a big outlay for a small town like Ama, but it has paid off, as vacuum-packed Ama seafood products soon found new markets around the country.

Just-caught swordtip squid is vacuum-packed (bottom row, right) using CAS freezing technology to lock in freshness (top row). Strips of marinated squid sashimi, laid on a bowl of rice, is a popular dish at the Ritō Kitchen restaurant in Asakusa, Tokyo (bottom row, left).

Just-caught swordtip squid is vacuum-packed (bottom row, right) using CAS freezing technology to lock in freshness (top row). Strips of marinated squid sashimi, laid on a bowl of rice, is a popular dish at the Ritō Kitchen restaurant in Asakusa, Tokyo (bottom row, left).

Sazae Curry and Oki Beef

This initial success led to a series of other hit products, including curry with sazae (horned turban), a type of mollusk—a dish also mentioned by Prime Minister Abe in his policy speech. It had long been standard fare in Ama, but it struck a chord with consumers nationwide when marketed in a ready-to-eat retort pouch. Another popular item was fresh Japanese oysters, developed by studying the various types grown all around Japan; only the highest quality oysters were marketed after being harvested in early spring, a strategy that led to a boost in demand from new markets.

Boxes of sazae pouch curry (left) and Haruka-brand Ama oysters.

Boxes of sazae pouch curry (left) and Haruka-brand Ama oysters.

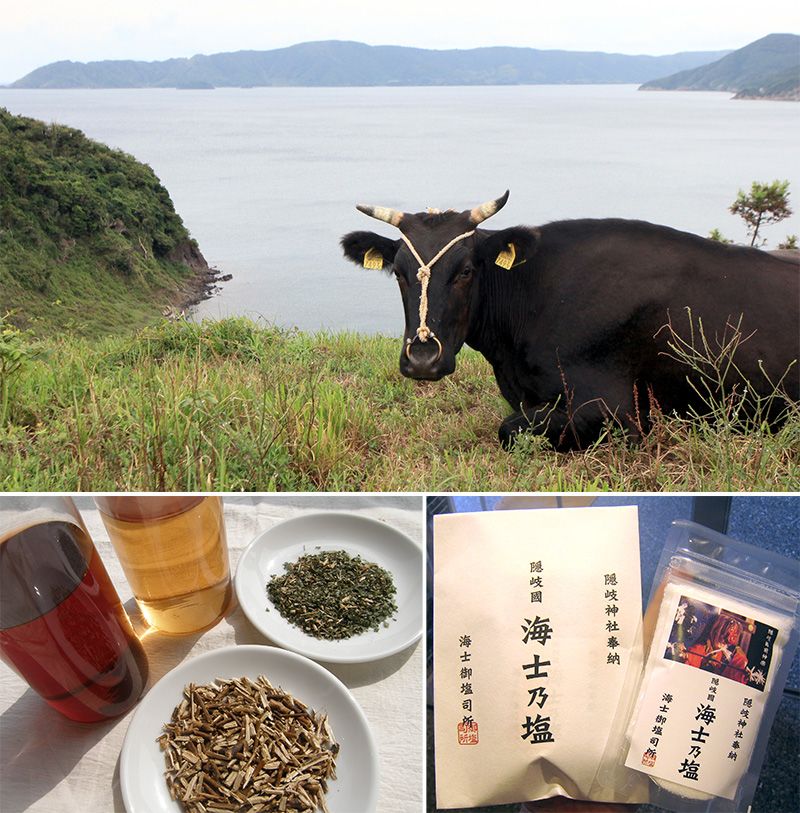

Ama-grown beef also became a hit. Cows in the Oki Islands have traditionally been allowed to graze freely and are known for their sturdy legs and loins. To avoid the high cost of shipping from remote islands, though, they were generally sold to other regions while still young calves. This trend was reversed when the very best mature cows that could win over discriminating consumers in Tokyo were branded as Oki beef and launched on the market. Although shipment volume is still limited, Oki-brand beef has earned accolades from epicureans all over the country. Other new products include handmade sea salt and natural fukugi tea made from locally grown ingredients. What were the factors behind Ama’s turnaround?

Oki-brand cows (top), born and raised on the island, are allowed to graze in Ama’s rich natural environment. Fukugi tea has a refreshing fragrance (above left). Ama salt (above right) is handmade using traditional methods from the waters of Hobomi Bay.

Oki-brand cows (top), born and raised on the island, are allowed to graze in Ama’s rich natural environment. Fukugi tea has a refreshing fragrance (above left). Ama salt (above right) is handmade using traditional methods from the waters of Hobomi Bay.

Fresh Blood

The secret to Ama’s newfound success is the presence of young newcomers, as I mentioned at the outset. In addition to stirring themselves to action, residents took the bold step of ushering in fresh blood: during the 10 years since 2004, Ama saw 437 people (294 households) move in—a surprisingly high number when one considers that the island’s total population is just 2,300. Most of these I-turn residents have been in their twenties, thirties, or forties, and a high percentage have settled down. What prompted these young people to move to this remote island community?

Many of them were lured to Ama by a scheme under which “trainees” are provided with housing, a variety of local services, and a monthly stipend to develop attractive new products with the island’s resources. After their training period is over, they are free to either stay or move on. This respect for their freedom may be what sets Ama’s initiative apart from those of other municipalities, many of which have sought to entice newcomers with generous economic incentives while at the same time placing high expectations on their continued presence, which often creates a rift with old-time residents. Ama provides all the information and other support that newcomers need, but it also respects their free will and refrains from overly confining the activities of the new residents.

I-turn trainees who come up with promising ideas receive support for pilot implementation at publicly built, privately operated facilities. A number of the items that I described above were launched as an outgrowth of this trainee program. The fresh perspectives brought by the newcomers led to the “rediscovery” of highly attractive aspects of life in Ama that had been taken for granted by longtime residents, and the conscious, strategic effort made to market such treasures has probably been the biggest reason for Ama’s success to date.

Synthesis of New and Old

Ama cannot be said to have been truly revitalized, though, unless the newcomers become fully integrated into the community. Ama’s fourth comprehensive development plan was thus drafted with the aim of promoting exchange and achieving synthesis between the new and old residents. Many municipal development plans tend to be either just a dry list of numbers or a collection of rosy goals that is short on specifics. Ama’s plan, by contrast, is full of helpful illustrations and suggestions for concrete action.

Residents new and old, aged 15 to 70, actively took part in the drafting of Ama’s latest development plan, released together with the report “24 Proposals for Ama’s Future.” (Photo courtesy of Studio-L)

Residents new and old, aged 15 to 70, actively took part in the drafting of Ama’s latest development plan, released together with the report “24 Proposals for Ama’s Future.” (Photo courtesy of Studio-L)

The theme of the plan was the pursuit of Ama’s happiness, and an attached report cites specific proposals for activities that can be undertaken by individual residents as well as by groups of 10 residents, 100 residents, and 1,000 residents. Examples include converting an unused nursery into a community hobby center and meeting space; thinning abandoned bamboo forests and using the felled trees to make charcoal; and building a “university” to preserve Ama’s traditional culture and hand down the skills and knowledge of local experts. These are accompanied by specific sources for further details and contact information for the relevant sections of the municipal government.

Four separate teams comprising residents and municipal officers were created to draft the plan over a period of a year. Community designer Yamazaki Ryō was invited to these meetings to offer advice. This intensive dialogue among the new and old residents no doubt made a significant contribution toward the building of an integrated community in Ama. The driving force for Ama’s growth may be such commitment to democratic self-determination, as exemplified in the residents’ own decision not to seek a merger with neighboring municipalities.

Spurred to action by a crisis that threatened its survival, the town of Ama has made remarkable efforts to determine its own future through dialogue among residents, the embracing of newcomers into the community, and the launching of new initiatives through a synthesis of the new and old. The model of regional revitalization in Ama offers many valuable hints for other communities throughout Japan confronting similar challenges.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 11, 2014. Photos courtesy of the Ama Town Office, unless otherwise noted.)

aging community population decline Falling birthrate regional revitalization Masuda report Japan Policy Council Ama Town I-turn